Containers and Orchestration

EE 547 - Unit 2

Spring 2026

Outline

Infrastructure Foundations

Running Distributed Components

- Server utilization and hardware economics

- Dependency conflicts on shared OS

- Ports multiplex traffic to processes

- TCP reliability vs UDP speed

- Layered responsibilities

- VLANs and logical separation

- Hypervisor presents virtual hardware

- Type 1 vs Type 2 architectures

Containers and Tooling

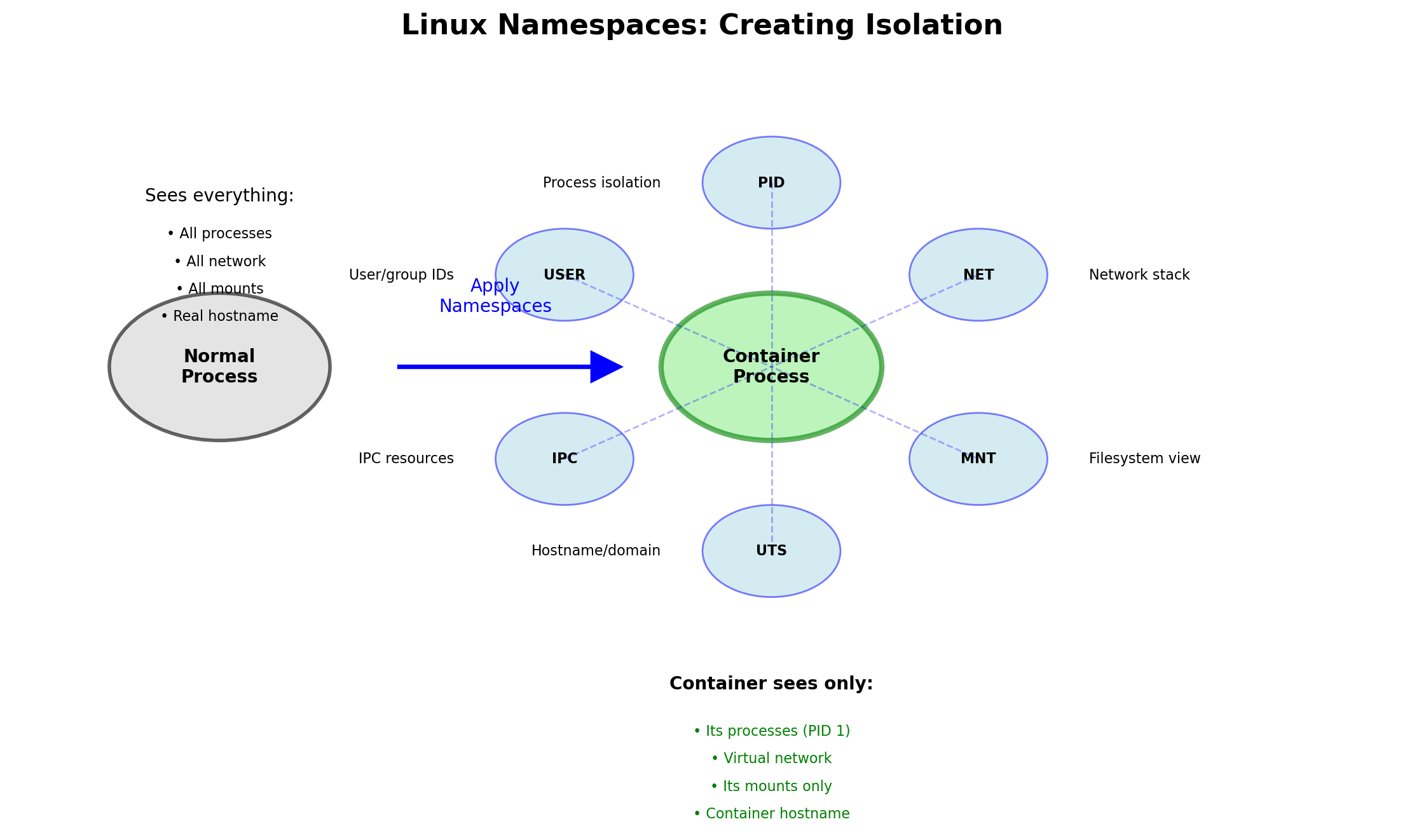

- Kernel namespaces filter process views

- Cgroups enforce resource limits

- Shared kernel trade-offs

- Layered images and running containers

- Port mapping, volumes, networks

- Declarative multi-container definitions

- Kubernetes pods, deployments, services

- Single-host vs cluster management

Running Distributed Components

A Web Application Requires Multiple Processes

Consider a web application serving users:

- Web servers accept HTTP connections, serve static files, route requests

- Application servers execute business logic, process requests

- Database stores persistent data, handles queries

- Cache holds frequently-accessed data in memory

- Background workers process async jobs, send emails

Each component is a separate process. The web server cannot directly call functions in the database—it sends queries over the network and waits for responses.

This separation exists for good reasons: different resource needs, different scaling characteristics, different failure modes.

Each Process Needs Resources to Run

A process consumes physical resources:

CPU — executes instructions, handles requests

The database process needs CPU to parse queries, execute plans, return results. The web server needs CPU to handle HTTP parsing, TLS termination, response generation.

Memory — holds working data, caches, buffers

PostgreSQL keeps frequently-accessed data pages in shared buffers. Redis holds its entire dataset in RAM. The JVM needs heap space for application objects.

Disk — stores persistent data, logs, temporary files

Database files, transaction logs, uploaded content. SSDs for fast random access, HDDs for bulk storage.

Network — communicates with other processes, serves clients

Bandwidth for request/response traffic. Connections to databases, caches, external APIs.

These resources come from physical hardware. Servers in a datacenter, instances in the cloud. Hardware that costs money.

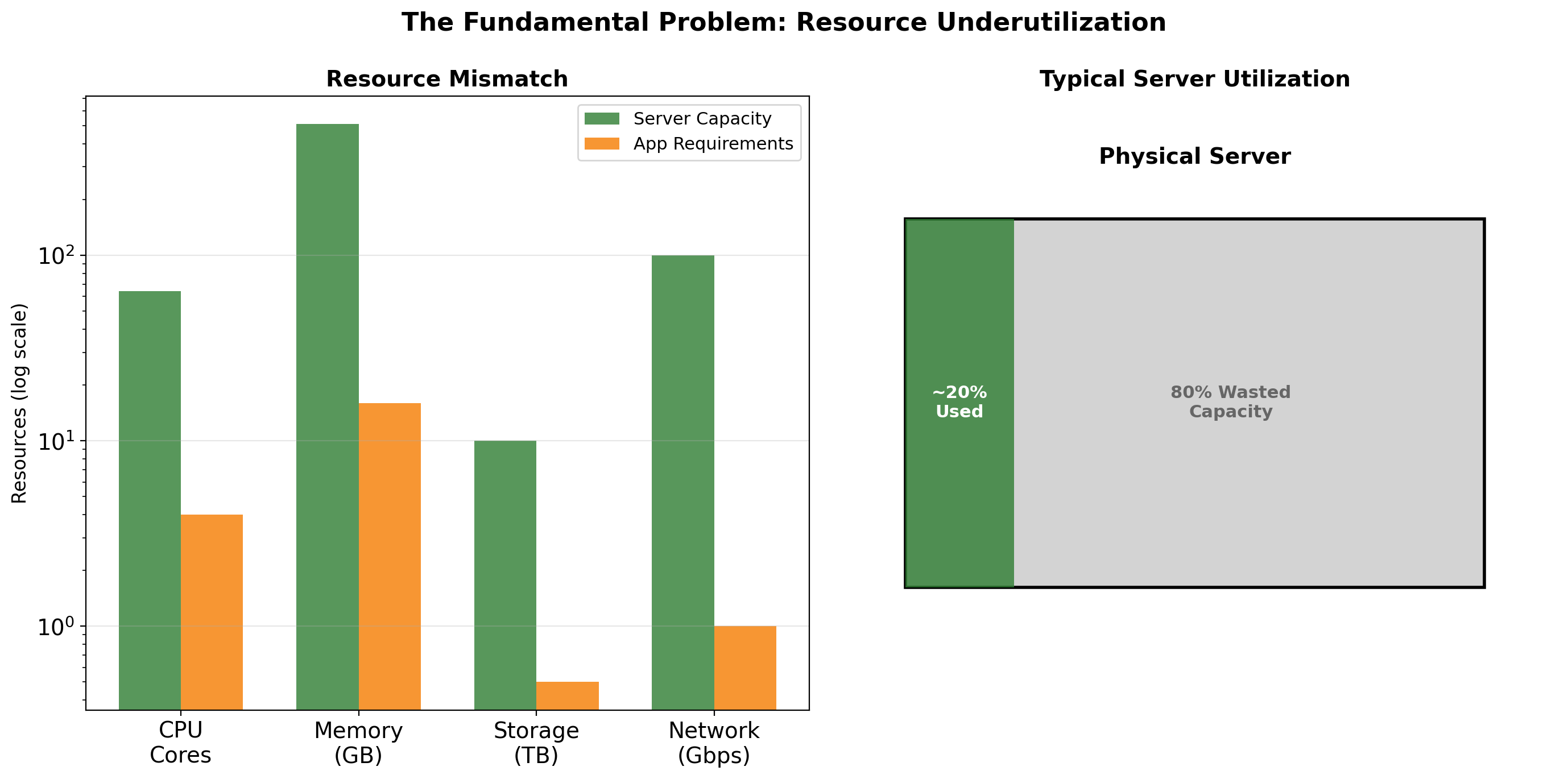

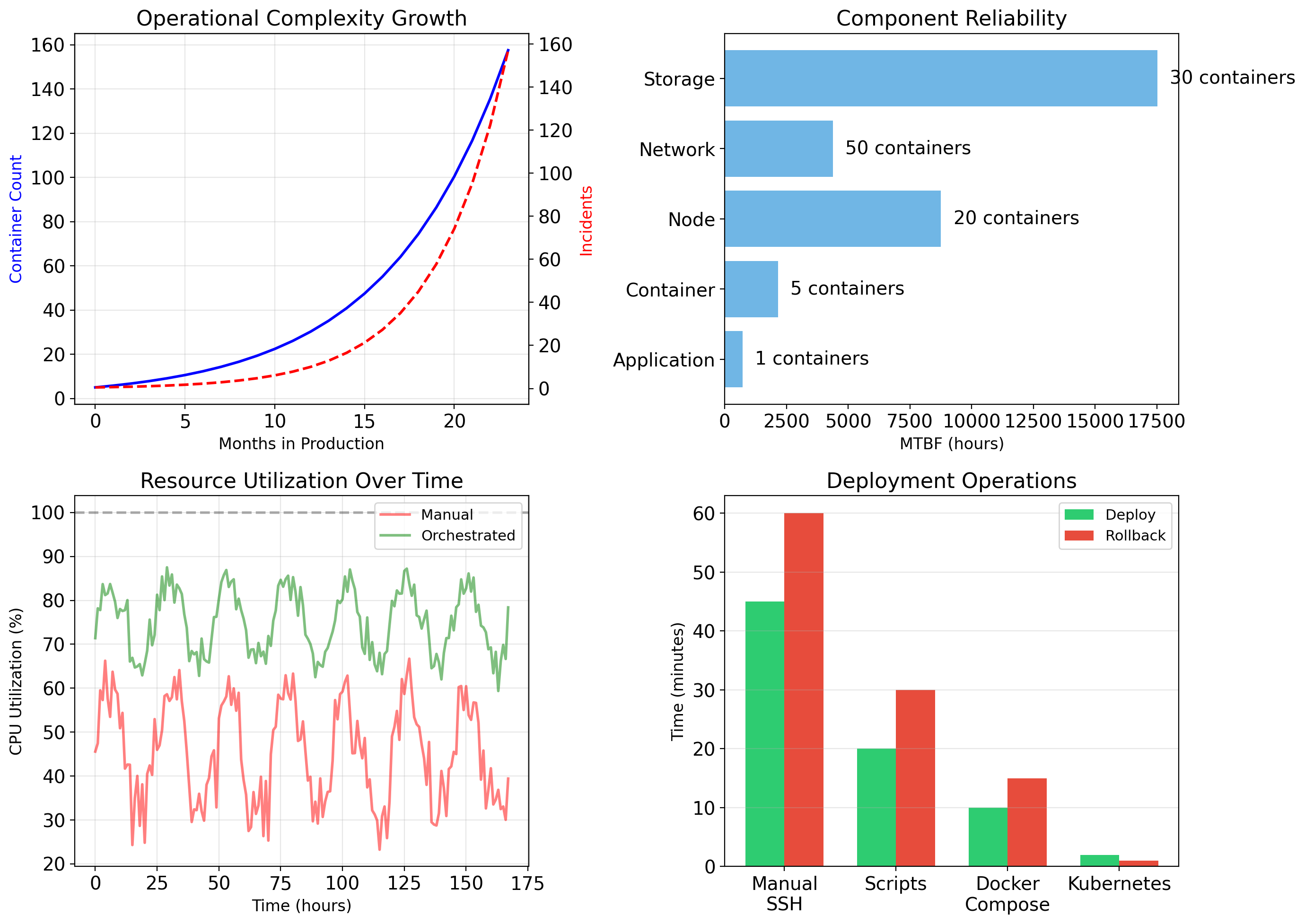

Dedicated Servers Sit Mostly Idle

If each component runs on its own physical server, utilization is typically 10-20%.

Why so low?

Servers are sized for peak load, not average load. The database server needs enough CPU to handle the traffic spike at 9am Monday. The rest of the week, most of that capacity sits unused.

Traffic patterns are bursty. A request takes 50ms of CPU time, then the server waits for the next request. Even under “heavy load,” CPUs spend most cycles waiting.

Redundancy requires spare capacity. If one app server fails, others must absorb its traffic. That headroom exists as idle capacity during normal operation.

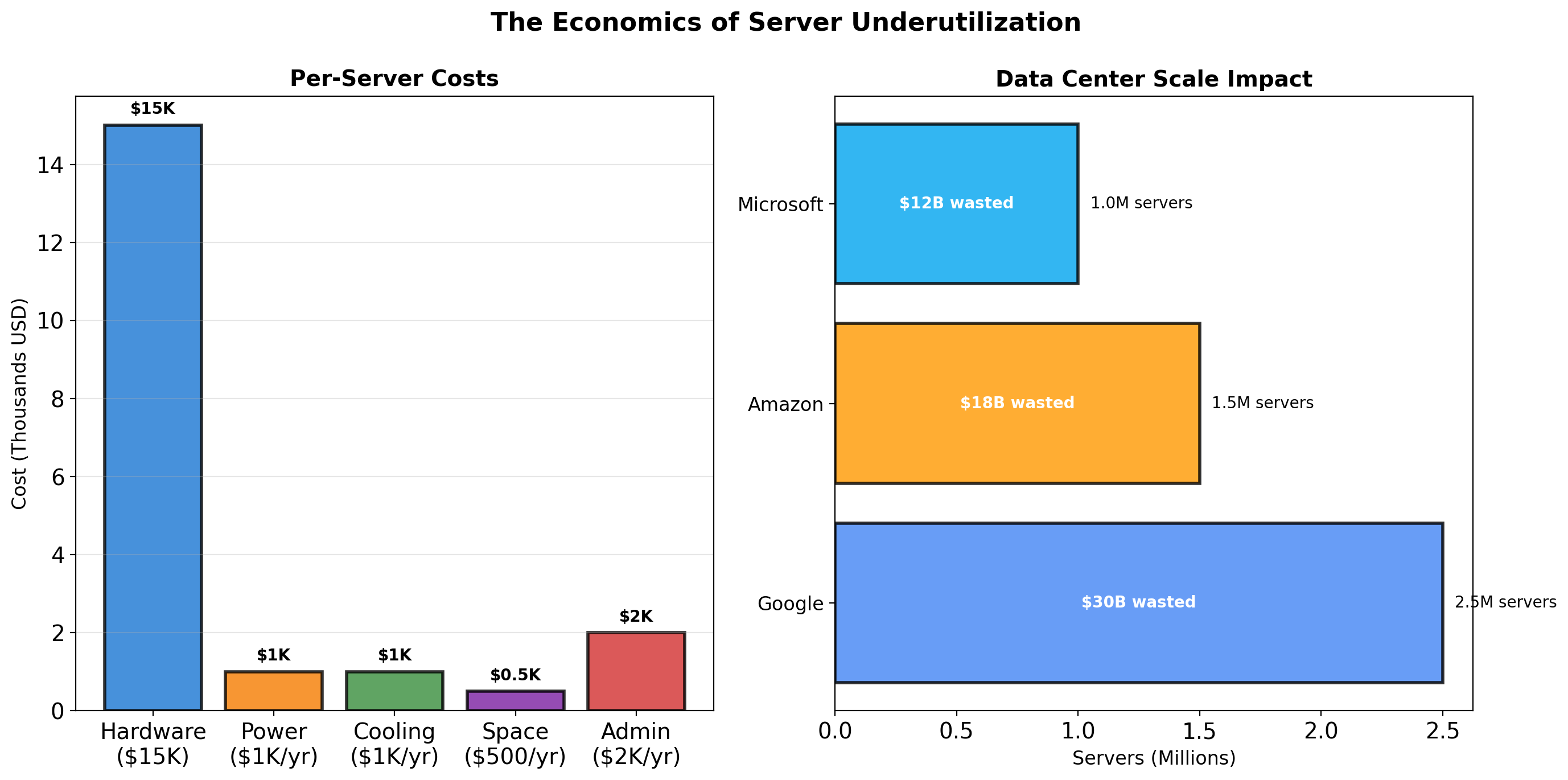

The Cost of Idle Hardware

A mid-range server costs approximately:

| Component | Cost |

|---|---|

| Server hardware | $8,000 - $15,000 |

| Amortized over 3-4 years | ~$250/month |

| Power (400W × 24/7) | ~$35/month |

| Cooling (40% of power) | ~$14/month |

| Rack space, networking | ~$50/month |

| Total cost of ownership | ~$350/month |

At 15% average utilization, the effective cost is:

\[\frac{\$350/\text{month}}{0.15} = \$2,333/\text{month per utilized server-equivalent}\]

Five physical servers doing the work of less than one.

At datacenter scale—thousands of servers—this waste represents millions of dollars annually. The economic pressure to improve utilization drove the development of virtualization technology.

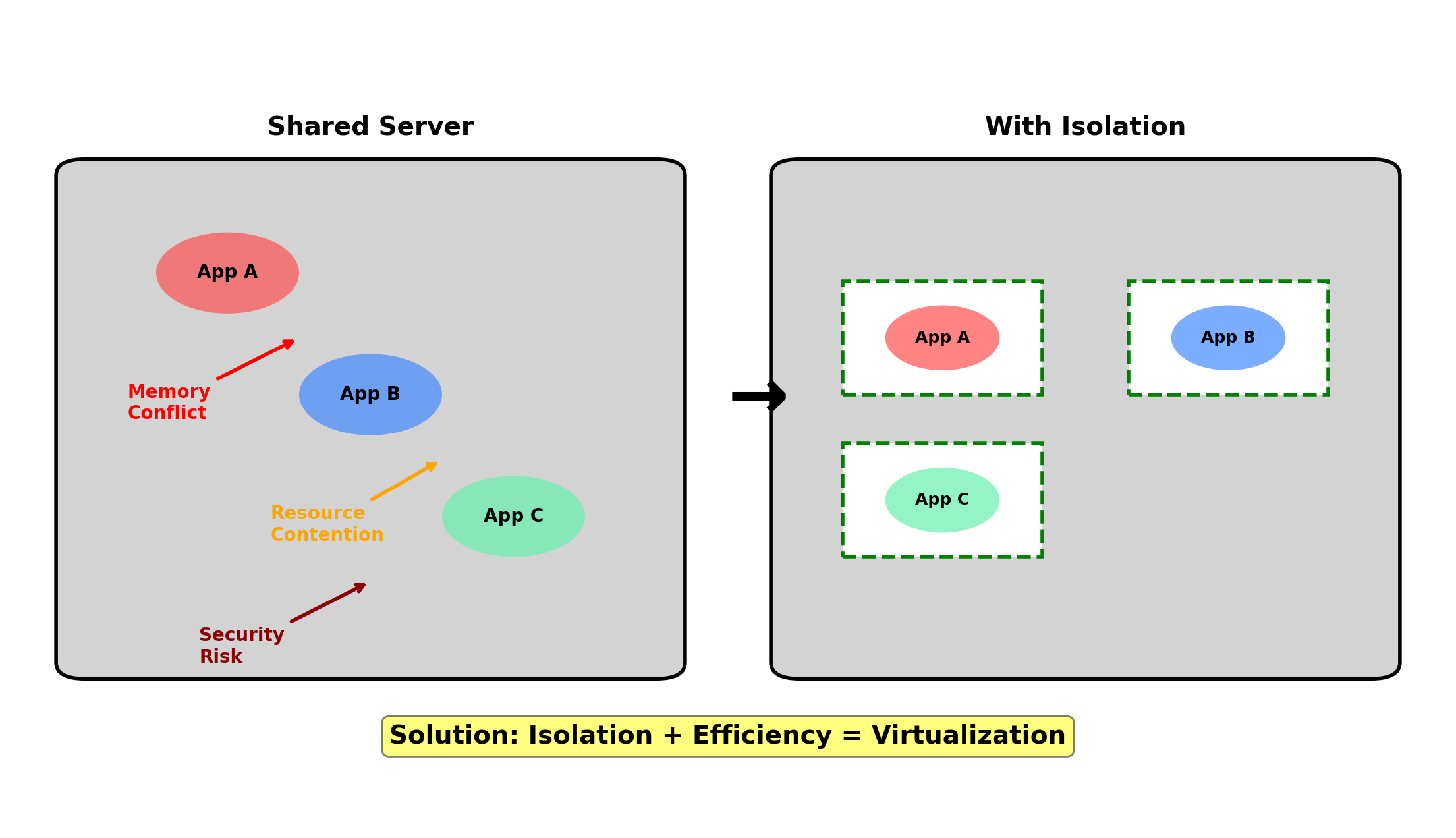

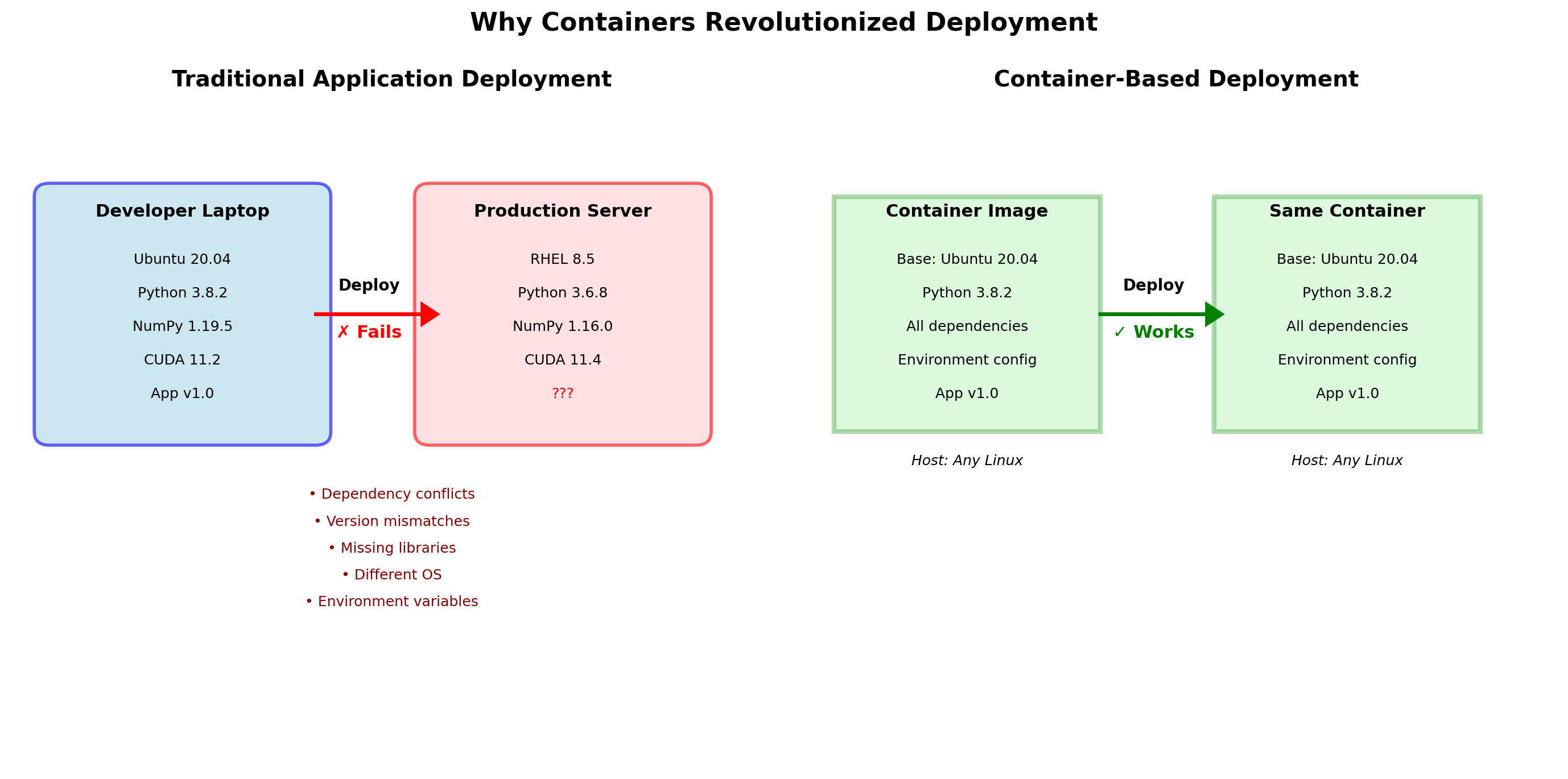

Running Multiple Applications on One Server

The obvious solution: put multiple applications on the same physical server.

If each application averages 15% utilization, four applications together might achieve 50-60% utilization. Better economics.

But applications share more than hardware—they share the operating system. This creates problems.

Dependency Conflicts Break Co-located Applications

Application A is a legacy system written in 2019.

- Requires Python 3.7

- Uses

requestslibrary version 2.22 - Depends on OpenSSL 1.1.1

Application B is a new service deployed this year.

- Requires Python 3.11

- Uses

requestslibrary version 2.31 - Depends on OpenSSL 3.0

Both cannot run on the same OS installation. Python 3.7 and 3.11 have incompatible syntax. OpenSSL 1.1.1 and 3.0 have incompatible ABIs.

Virtual environments help with Python packages but not with system libraries. The OpenSSL conflict has no clean solution without OS-level isolation.

Resource Contention Affects All Applications

Applications on the same OS compete for resources without isolation.

Memory pressure

Application A has a memory leak. It slowly consumes available RAM. The OS starts swapping. Application B—completely unrelated—slows to a crawl because its memory pages are on disk.

CPU starvation

Application A enters a busy loop due to a bug. It consumes 100% of available CPU. Application B cannot process requests—no CPU cycles available.

Disk I/O saturation

Application A performs a bulk data export, writing gigabytes to disk. Application B’s database queries slow down—the disk is busy serving A’s writes.

The OS provides no mechanism to prevent one application from affecting another. They share a single pool of resources.

Security Boundaries Do Not Exist

Applications on the same OS can access each other’s data.

Filesystem access

Application A stores API keys in /etc/app-a/secrets.conf. Application B, running as the same user, can read that file. A vulnerability in B exposes A’s credentials.

Process visibility

Application A can list all processes with ps aux. It sees Application B’s command-line arguments, which might include database passwords.

Network access

Application A can bind to any port. It could intercept traffic meant for Application B by binding to B’s port first (if B restarts).

Shared users and permissions

If both run as www-data, they have identical filesystem permissions. Compromising one means compromising both.

Operational Coupling Creates Cascading Failures

OS updates affect all applications

A kernel security patch requires a reboot. All five applications go down simultaneously. Coordinating maintenance windows across unrelated teams becomes a scheduling nightmare.

One crash can affect others

Application A triggers a kernel panic (bad driver, memory corruption). All applications on that server die. Unrelated services suffer an outage.

Restart order matters

Application A starts before Application B. A grabs port 8080. B, which was supposed to use 8080, fails to start. Manual intervention required.

Log and metric confusion

All applications write to /var/log. Disk fills up—whose logs are responsible? System metrics show high CPU—which application is the cause?

The Requirements Are Clear

Running distributed components requires:

Isolation

- Separate dependency environments

- Resource limits per workload

- Security boundaries between applications

- Independent failure domains

Each component should be able to crash, update, or misbehave without affecting others.

Efficiency

- High hardware utilization

- Shared infrastructure costs

- Fast deployment and scaling

- Minimal resource overhead

The cost of isolation should not negate the benefits of consolidation.

Dedicated physical servers provide isolation but waste resources. Shared OS installations provide efficiency but no isolation.

The technologies in this lecture—virtualization and containers—provide mechanisms to achieve both. Each makes different trade-offs between isolation strength and overhead.

Before Isolation Mechanisms: Networking

Isolated components still need to communicate. A database in its own isolated environment is useless if applications cannot query it.

Understanding how processes communicate over networks is prerequisite to understanding:

- How virtual machines present virtual network interfaces

- How containers isolate network namespaces

- How port mapping connects isolated containers to the outside world

- How services discover each other

Networking is not the focus of this course. But the basic model—processes binding to ports, TCP connections, request/response patterns—underpins everything that follows.

Network Communication

A Process Listens on a Port

A web server starts and binds to port 80.

import socket

server = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

server.bind(('0.0.0.0', 80))

server.listen(5)

while True:

client, addr = server.accept()

# handle requestThe process tells the operating system: “Send me any TCP traffic that arrives on port 80.”

The OS maintains a table mapping ports to processes. When a packet arrives destined for port 80, the kernel delivers it to this process.

Port numbers range from 0-65535. Ports below 1024 require elevated privileges (root/admin) on most systems.

Ports Multiplex Traffic to a Single Machine

A server has one IP address, but runs many network-facing processes. The web server, database, cache, and SSH daemon all need to receive traffic.

The problem: When a packet arrives at 192.168.1.10, which process should receive it?

The solution: Port numbers. Each packet carries a destination port. The OS uses this to route traffic to the correct process.

A port is an address within a machine. The IP address gets the packet to the right machine. The port gets it to the right process.

Destination: 192.168.1.10:5432

└─────┬─────┘ └┬─┘

machine processThe combination of IP address and port uniquely identifies a network endpoint.

Multiple Processes Use Different Ports

A single machine can run many network services. Each binds to a different port.

| Port | Service | Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | SSH | Remote shell access |

| 80 | HTTP | Unencrypted web traffic |

| 443 | HTTPS | Encrypted web traffic |

| 5432 | PostgreSQL | Database queries |

| 6379 | Redis | Cache operations |

| 8080 | Application | Common alternative HTTP |

Only one process can bind to a given port. If nginx is listening on port 80, no other process can bind to 80. Attempting to do so returns “Address already in use.”

This constraint becomes important with containers: two containers both wanting port 80 on the same host need a resolution mechanism.

Clients Connect to Address and Port

To communicate with a service, a client needs two pieces of information:

IP address — identifies the machine

Port — identifies the process on that machine

import socket

client = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

client.connect(('192.168.1.10', 5432))

client.send(b'SELECT * FROM users')

response = client.recv(4096)The combination 192.168.1.10:5432 fully specifies the destination.

The client also uses a port—the OS assigns an arbitrary unused port (ephemeral port, typically 49152-65535) for the client side of the connection.

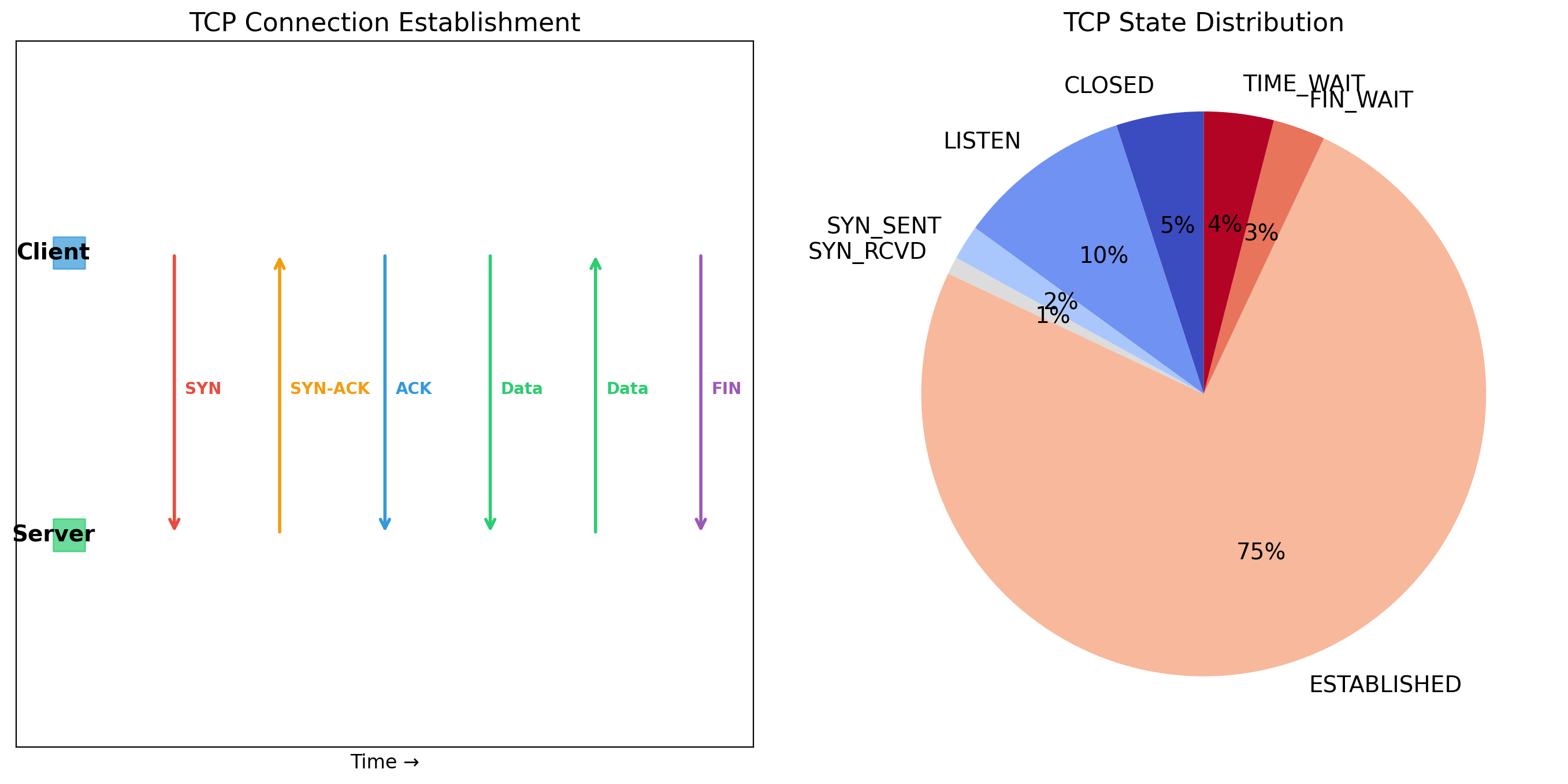

TCP Provides Reliable, Ordered Delivery

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) handles complexity that applications shouldn’t deal with:

Reliable delivery

If a packet is lost, TCP retransmits it. The sender doesn’t receive acknowledgment within a timeout, so it sends again. The application sees reliable delivery without knowing about the loss.

Ordered delivery

Packets may arrive out of order due to network routing. TCP buffers and reorders them. The application receives bytes in the order they were sent.

Flow control

If the receiver is slow, TCP tells the sender to slow down. Prevents overwhelming the receiver’s buffers.

Connection-oriented

A connection is established before data transfer. Both sides know the other is present and ready.

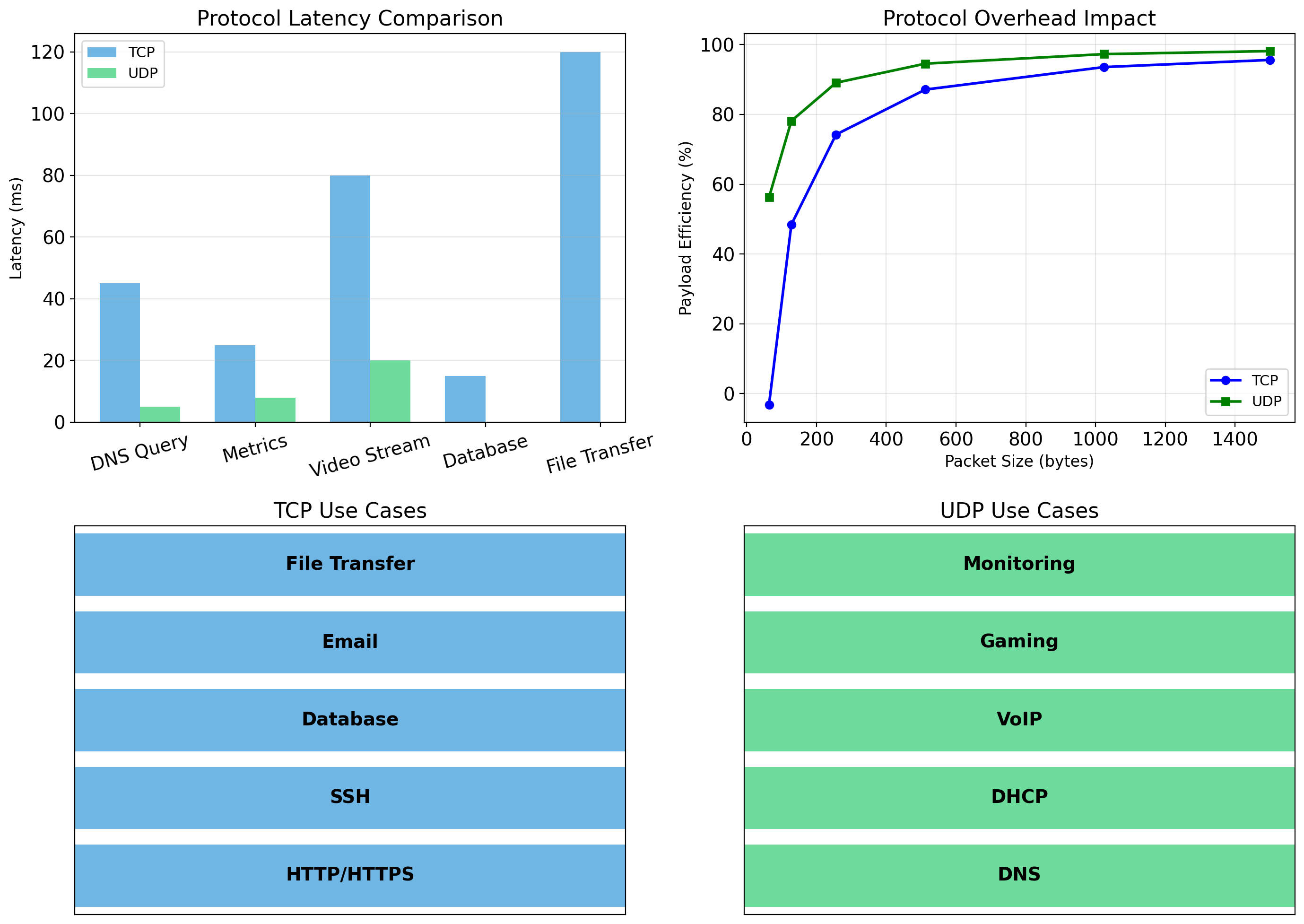

TCP Costs: Latency and Overhead

TCP’s guarantees come at a cost.

Connection setup

Before sending data, TCP performs a three-way handshake:

- Client sends SYN

- Server responds SYN-ACK

- Client sends ACK

One round-trip before any application data flows. For a server 50ms away, that’s 50ms of latency before the request even starts.

Head-of-line blocking

If packet 3 arrives before packet 2, TCP buffers packet 3 and waits. The application cannot see packet 3 until packet 2 arrives. Lost packet 2 blocks everything behind it.

Overhead

Every packet has a TCP header (20 bytes minimum). Acknowledgments consume bandwidth. Retransmission timers consume memory.

For most application traffic—HTTP requests, database queries, API calls—TCP’s guarantees are worth the cost. You want your database query to arrive complete and in order.

UDP: Unreliable but Fast

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) provides minimal service:

No connection setup

Send packets immediately. No handshake required.

No reliability

Packets may be lost. UDP does not retransmit.

No ordering

Packets may arrive out of order. UDP does not reorder.

No flow control

Sender can overwhelm receiver. UDP does not slow down.

Why use UDP?

When speed matters more than reliability. When the application handles reliability itself. When occasional loss is acceptable.

Video streaming: a dropped frame is better than pausing for retransmission. DNS queries: simple request/response, application can retry if needed.

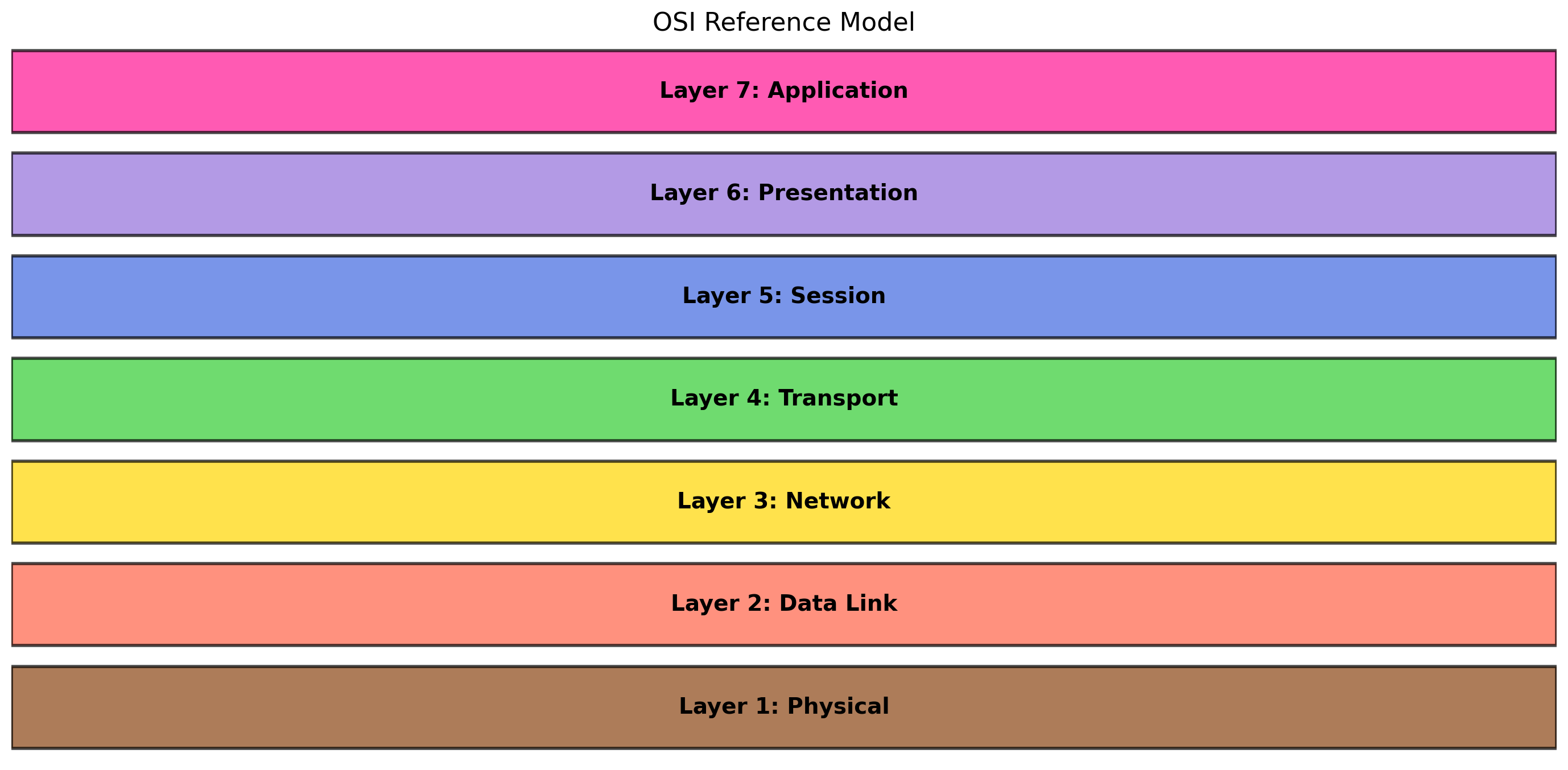

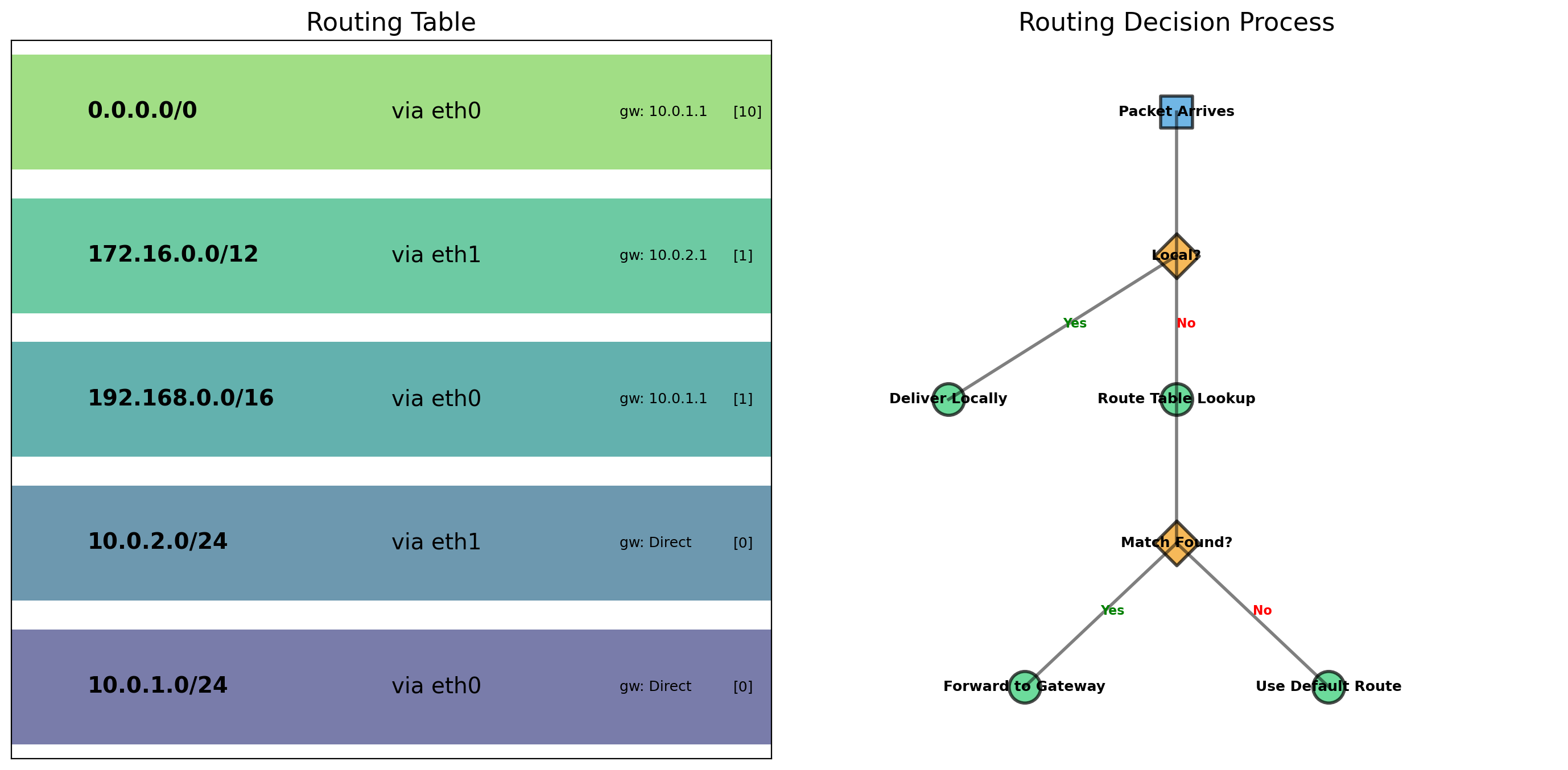

Network Layers Separate Responsibilities

Network communication is organized into layers, each handling a specific responsibility:

Application layer

Your code. HTTP requests, database queries, API calls. Deals with application-level semantics.

Transport layer

TCP or UDP. Handles reliability (or not), port multiplexing, connection management. Delivers data to the right process.

Network layer

IP. Handles addressing and routing. Gets packets from source machine to destination machine across potentially many intermediate routers.

Link layer

Physical delivery on a local network segment. Ethernet, WiFi. Gets frames to the next hop.

Each layer uses the services of the layer below without knowing its implementation details.

Your Code Lives at the Application Layer

When your application sends an HTTP request:

You don’t specify:

- How to establish a TCP connection

- How to handle packet loss

- How to route to

api.example.com - Which network interface to use

The layers below handle all of that. Your application layer code expresses intent: “GET the resource at this URL.” The transport layer establishes a reliable connection. The network layer routes packets to the destination. The link layer transmits frames on the wire.

This separation means your application code works regardless of whether you’re on WiFi, Ethernet, or a mobile network.

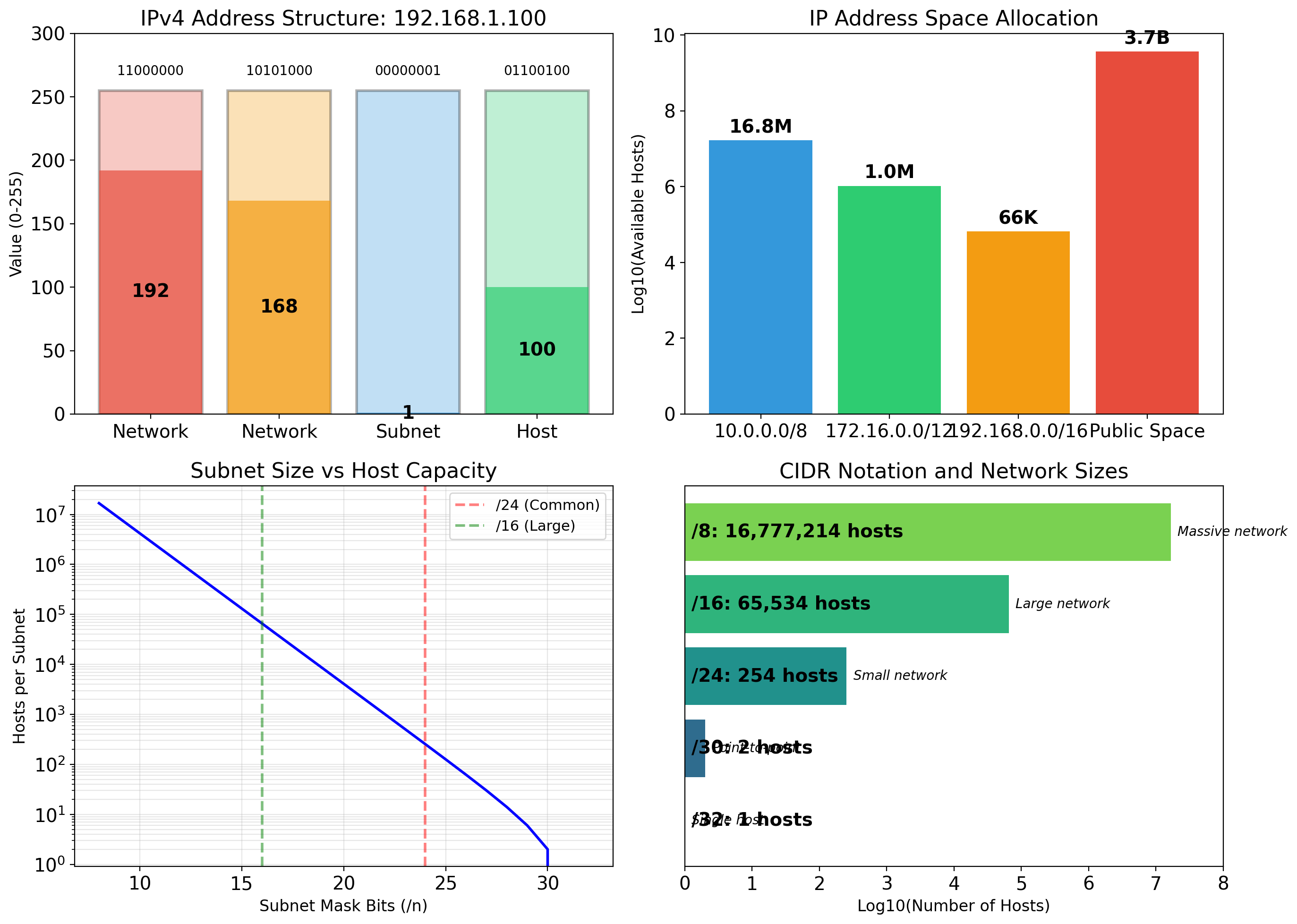

IP Addresses Identify Machines

Every machine on a network has an IP address.

IPv4 addresses

Four numbers 0-255, separated by dots: 192.168.1.10

32 bits total, approximately 4.3 billion possible addresses. Running out—most of the public address space is allocated.

IPv6 addresses

Eight groups of hexadecimal: 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

128 bits, effectively unlimited addresses. Adoption growing but IPv4 still dominates.

Private address ranges

10.0.0.0/8— 16 million addresses172.16.0.0/12— 1 million addresses192.168.0.0/16— 65,000 addresses

Not routable on the public internet. Used within organizations, home networks, cloud VPCs.

DNS Translates Names to Addresses

IP addresses are hard to remember. DNS (Domain Name System) provides human-readable names.

When your application connects to api.example.com:

- Application calls

getaddrinfo("api.example.com") - OS checks local cache

- If not cached, queries DNS resolver

- Resolver queries DNS hierarchy

- Returns IP address(es)

- Application connects to that IP

DNS records have TTL (time-to-live). Clients cache responses for that duration. Allows servers to change IP addresses—clients eventually get the new address.

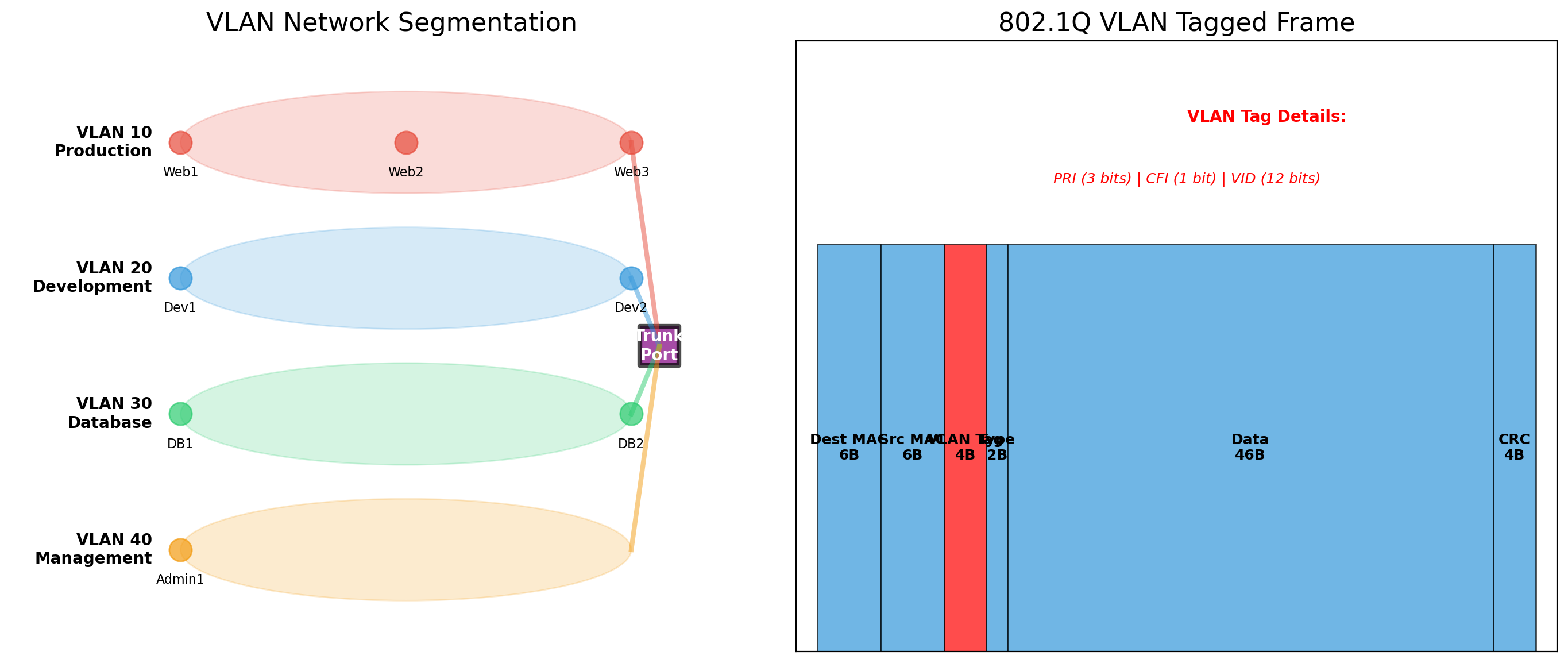

VLANs Provide Logical Network Separation

Physical networks can be logically partitioned using VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks).

Without VLANs

All devices on a switch can communicate directly. The marketing department’s printers are on the same network as engineering’s servers.

With VLANs

The switch tags traffic with VLAN IDs. VLAN 10 traffic only reaches VLAN 10 ports. Marketing and engineering are isolated even though they share physical infrastructure.

Why this matters

- Security: Limit blast radius of compromised devices

- Performance: Reduce broadcast traffic

- Organization: Group devices logically, not physically

Cloud providers use similar concepts. AWS VPCs, Azure VNets—logical network isolation on shared physical infrastructure.

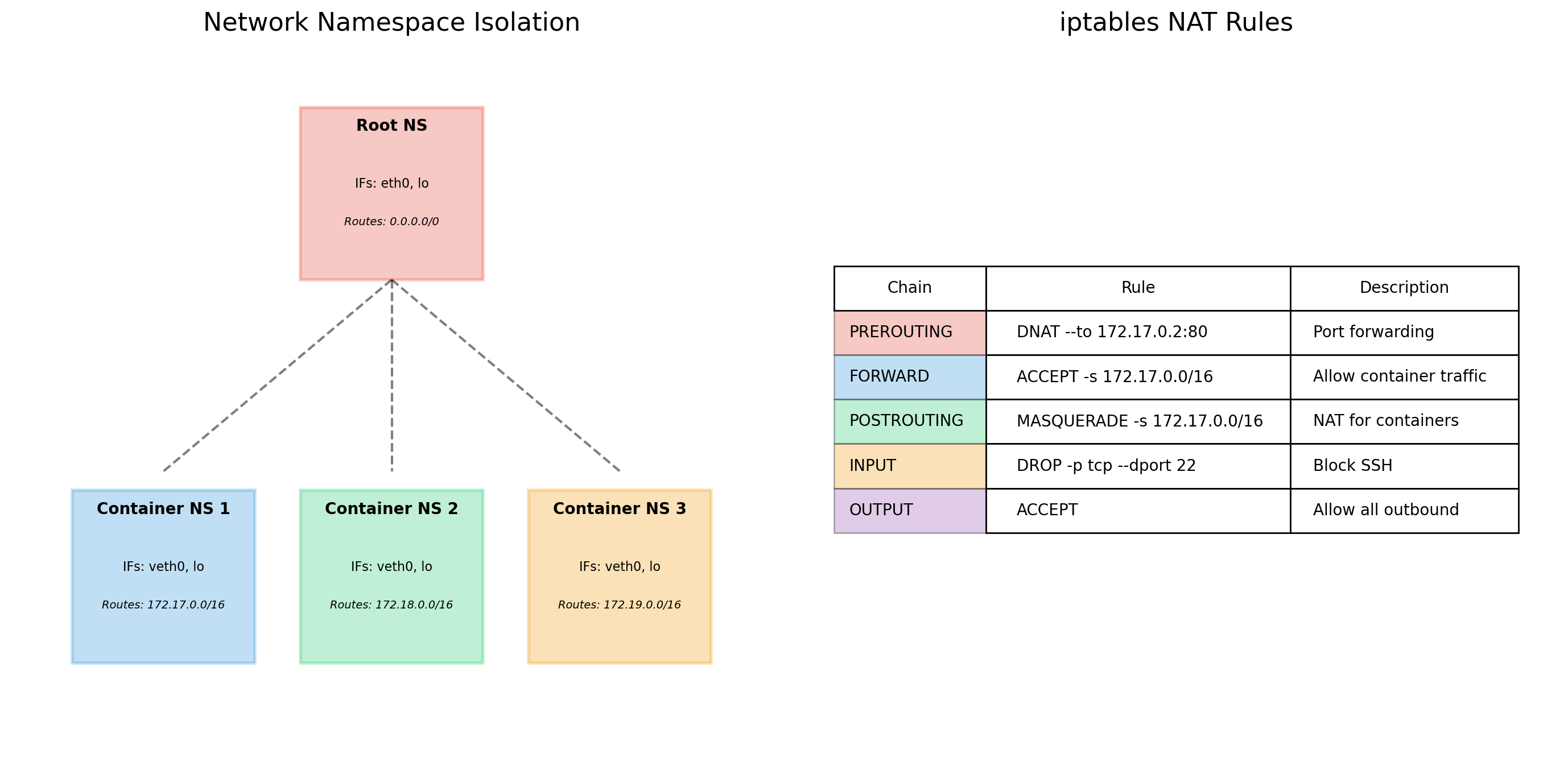

Networking Concepts Enable Container Isolation

The networking concepts covered here directly apply to container and VM networking:

Ports and binding

Containers bind to ports inside their namespace. Port mapping connects host ports to container ports.

IP addresses

Containers get their own IP addresses on virtual networks. Host acts as router between container networks and the outside world.

TCP/UDP

Container traffic uses the same protocols. Database connections inside containers are TCP just like outside.

DNS

Containers can resolve each other by name. Docker and Kubernetes provide internal DNS for service discovery.

Network isolation

Container networks are logically separated. Containers on different networks cannot communicate directly, similar to VLANs.

Understanding these primitives makes container networking comprehensible rather than magical.

Virtualization

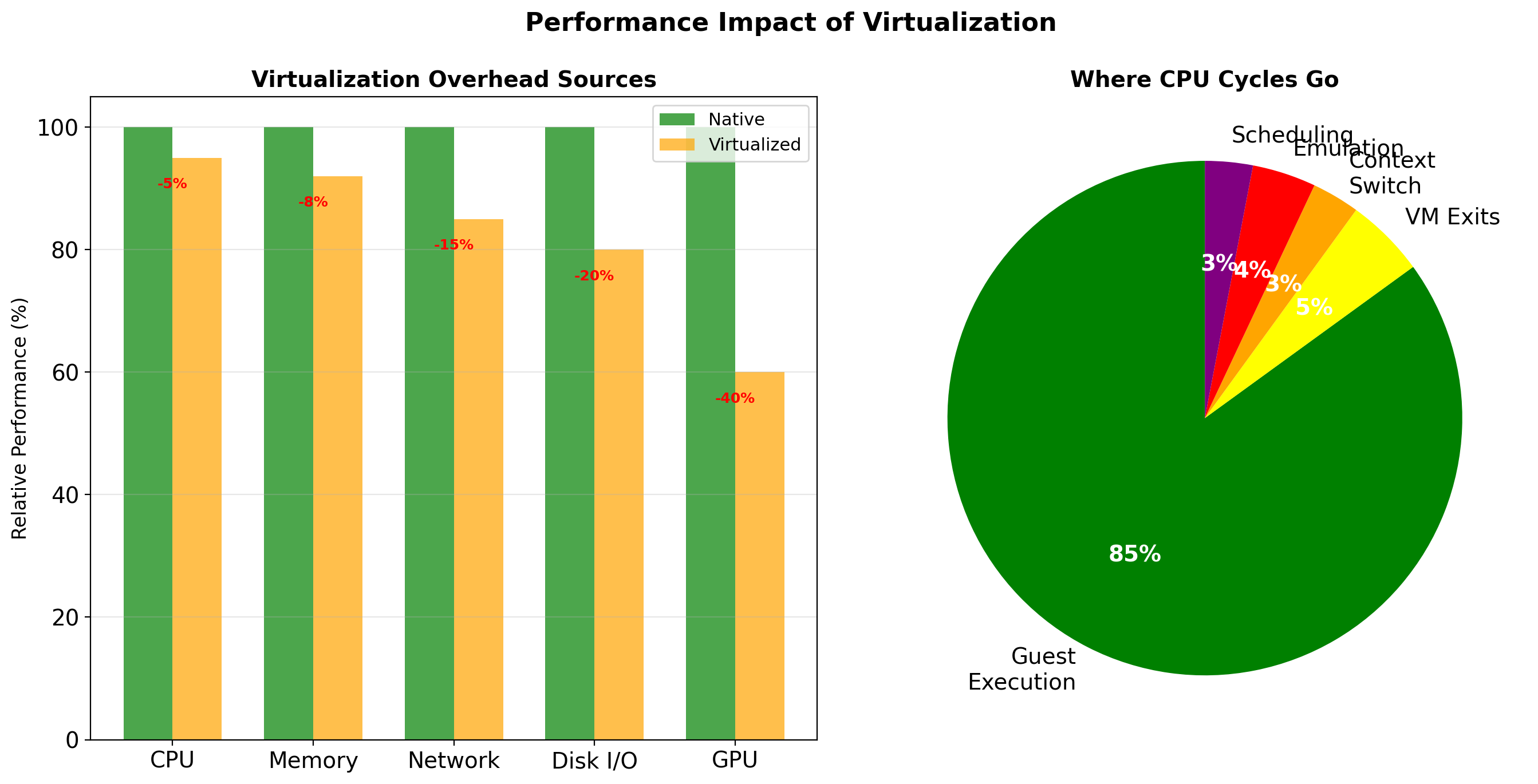

Dedicated Servers Waste Resources, Shared OS Creates Conflicts

Dedicated servers

Each workload gets its own machine. Complete isolation. But 10-20% utilization—85% of hardware sits idle.

Shared OS

Multiple workloads on one machine. Better utilization. But dependency conflicts, resource contention, security risks, coupled failures.

Neither option is acceptable at scale. Workloads need to:

- Run in separate environments

- Share underlying hardware

- Not interfere with each other

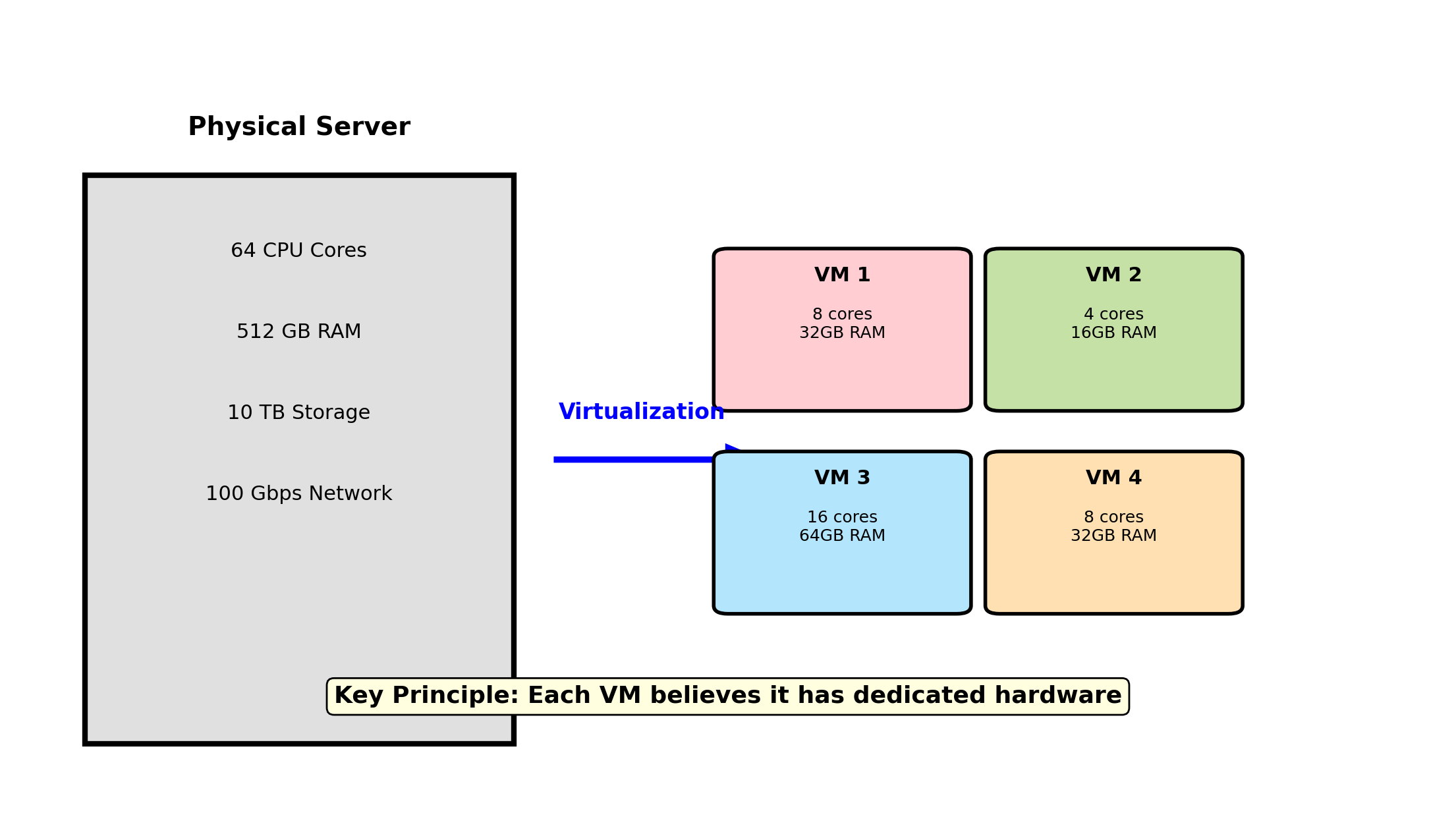

Virtual Machines Run Complete Operating Systems on Shared Hardware

A virtual machine (VM) sees:

- Its own CPU (or CPUs)

- Its own memory, starting at address 0

- Its own disk drives

- Its own network interfaces

The VM runs a full OS kernel. That kernel manages virtual hardware as if it were real. Applications run normally.

From inside: a dedicated physical machine.

From outside: software on shared hardware.

Isolation

- Separate kernels

- Separate memory spaces

- Separate filesystems

- Separate process tables

Efficiency

- Multiple VMs per physical server

- Resources allocated per-VM

- Unused capacity available to other VMs

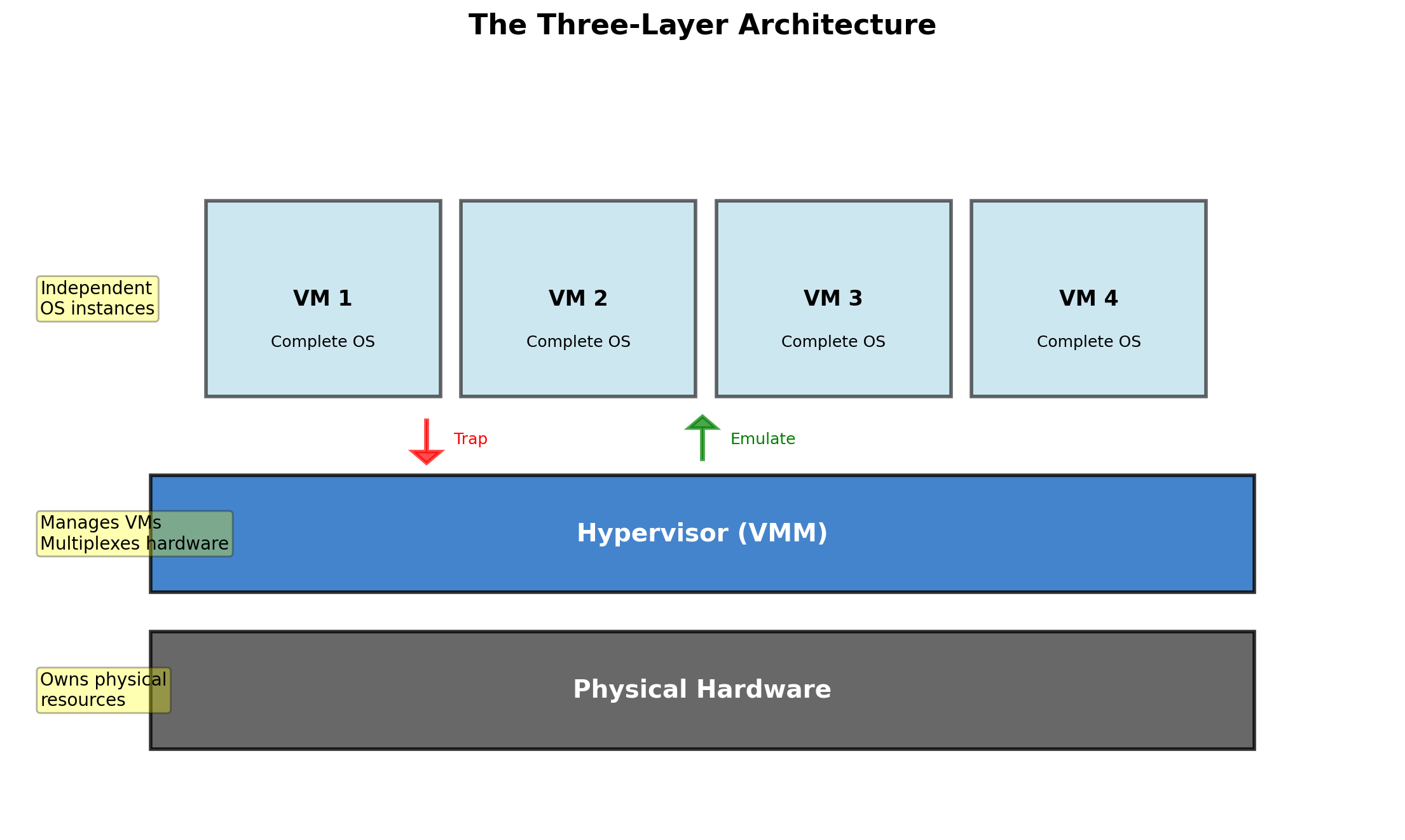

One Physical Machine, Multiple Virtual Machines

Each VM sees its own complete machine: CPU, memory, disk, network interfaces. The hypervisor divides physical resources among VMs and enforces isolation between them.

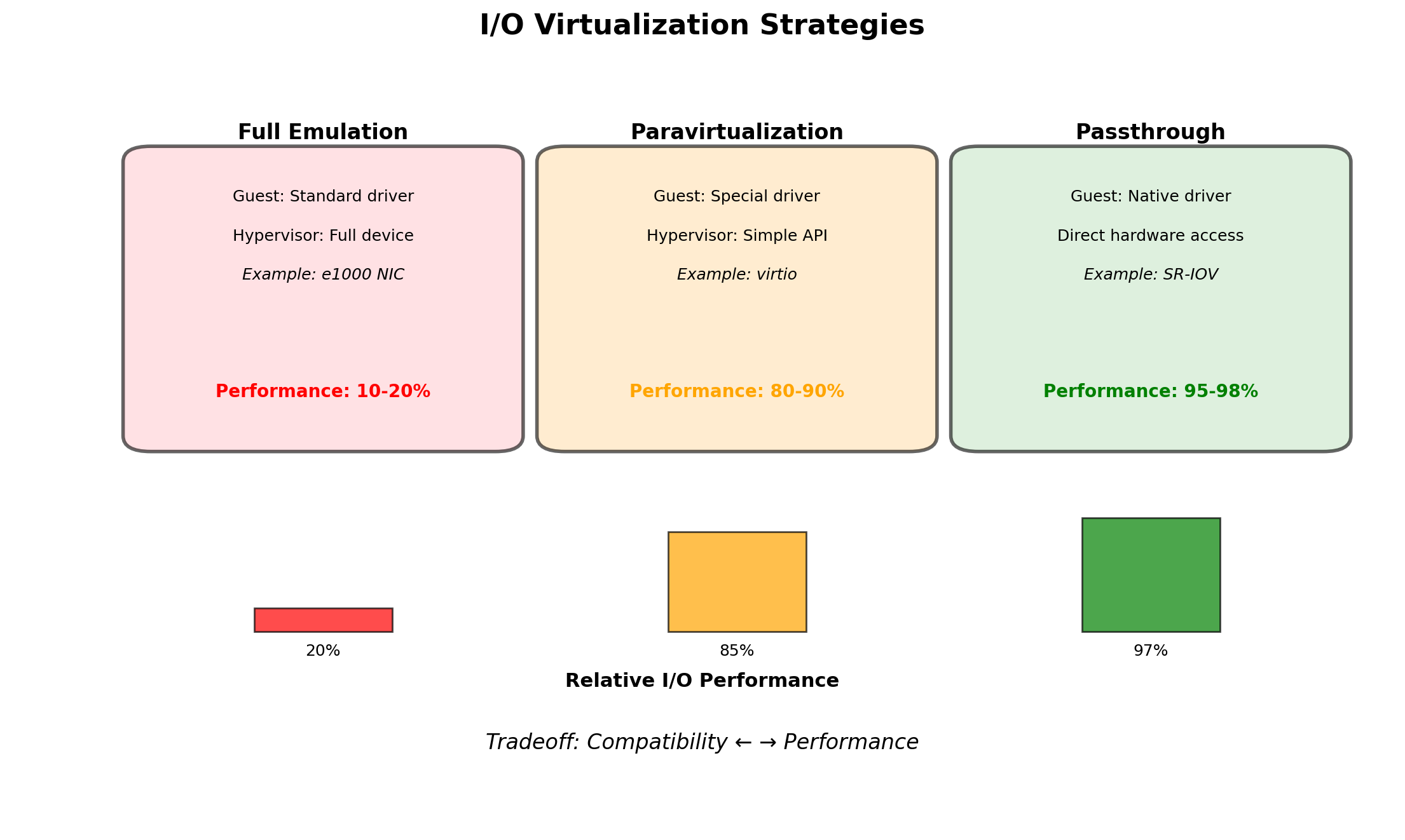

The Hypervisor Virtualizes Hardware

The hypervisor is a software layer that:

- Presents virtual hardware to each VM

- Schedules VM execution on physical CPUs

- Manages memory allocation across VMs

- Mediates access to physical devices

Each VM runs a full operating system. That OS believes it’s running on real hardware. The hypervisor maintains this illusion.

VMs cannot access each other’s memory, see each other’s processes, or interfere with each other’s operation. The hypervisor enforces these boundaries.

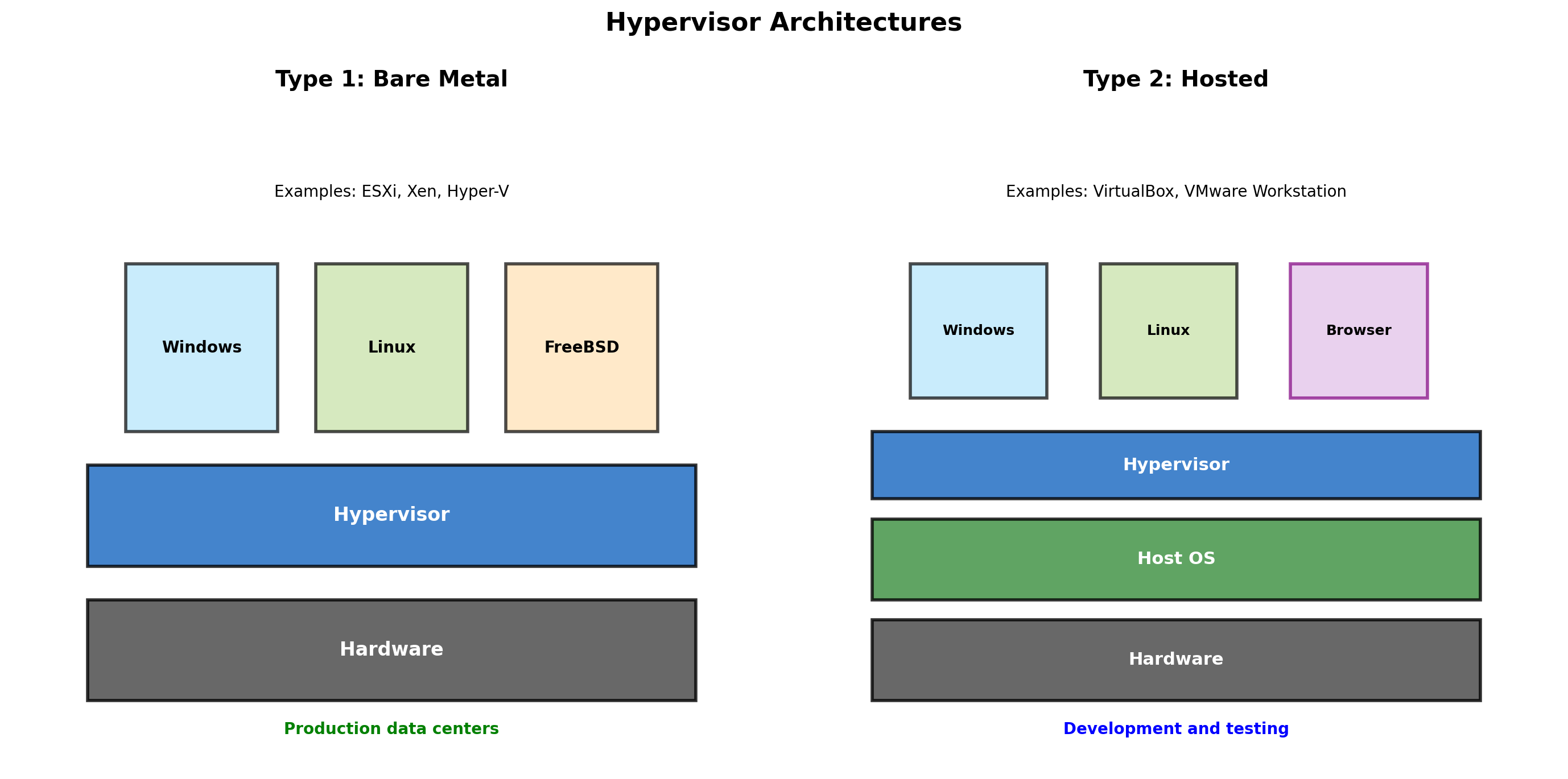

Type 1 Hypervisors Run on Bare Metal

Type 1 (bare metal)

The hypervisor runs directly on hardware. No host operating system underneath.

Examples:

- Xen — Powers AWS EC2

- VMware ESXi — Enterprise datacenters

- Microsoft Hyper-V — Windows Server

- KVM — Linux kernel module

Used in production environments where performance and isolation matter. The hypervisor is the operating system for the physical machine.

Type 2 Hypervisors Run on a Host OS

Type 2 (hosted)

The hypervisor runs as an application on a host operating system.

Examples:

- VirtualBox — Free, cross-platform

- VMware Workstation — Windows/Linux

- Parallels — macOS

- VMware Fusion — macOS

Used for development and desktop virtualization. Convenient—runs alongside normal applications. But an extra OS layer adds overhead.

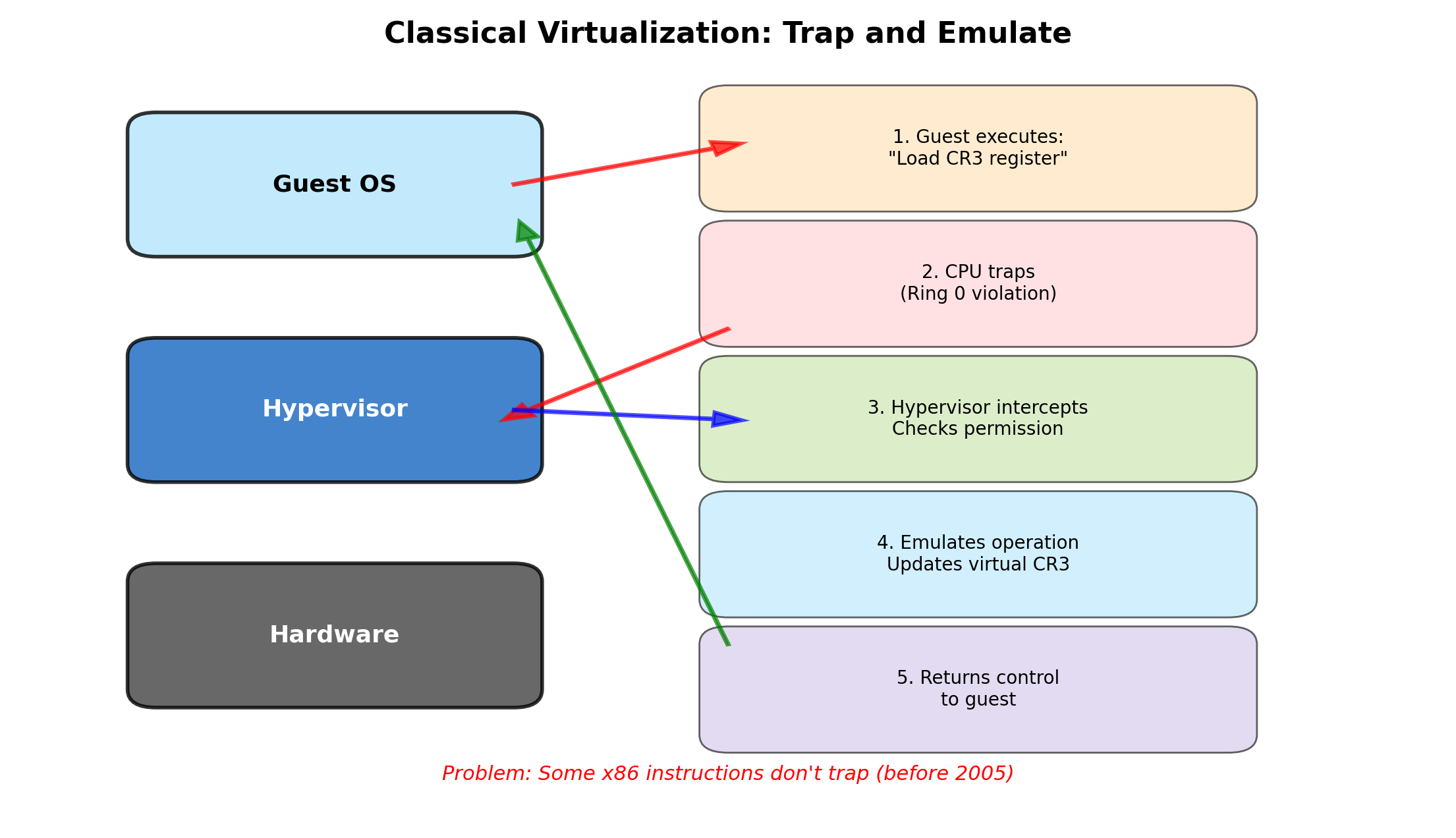

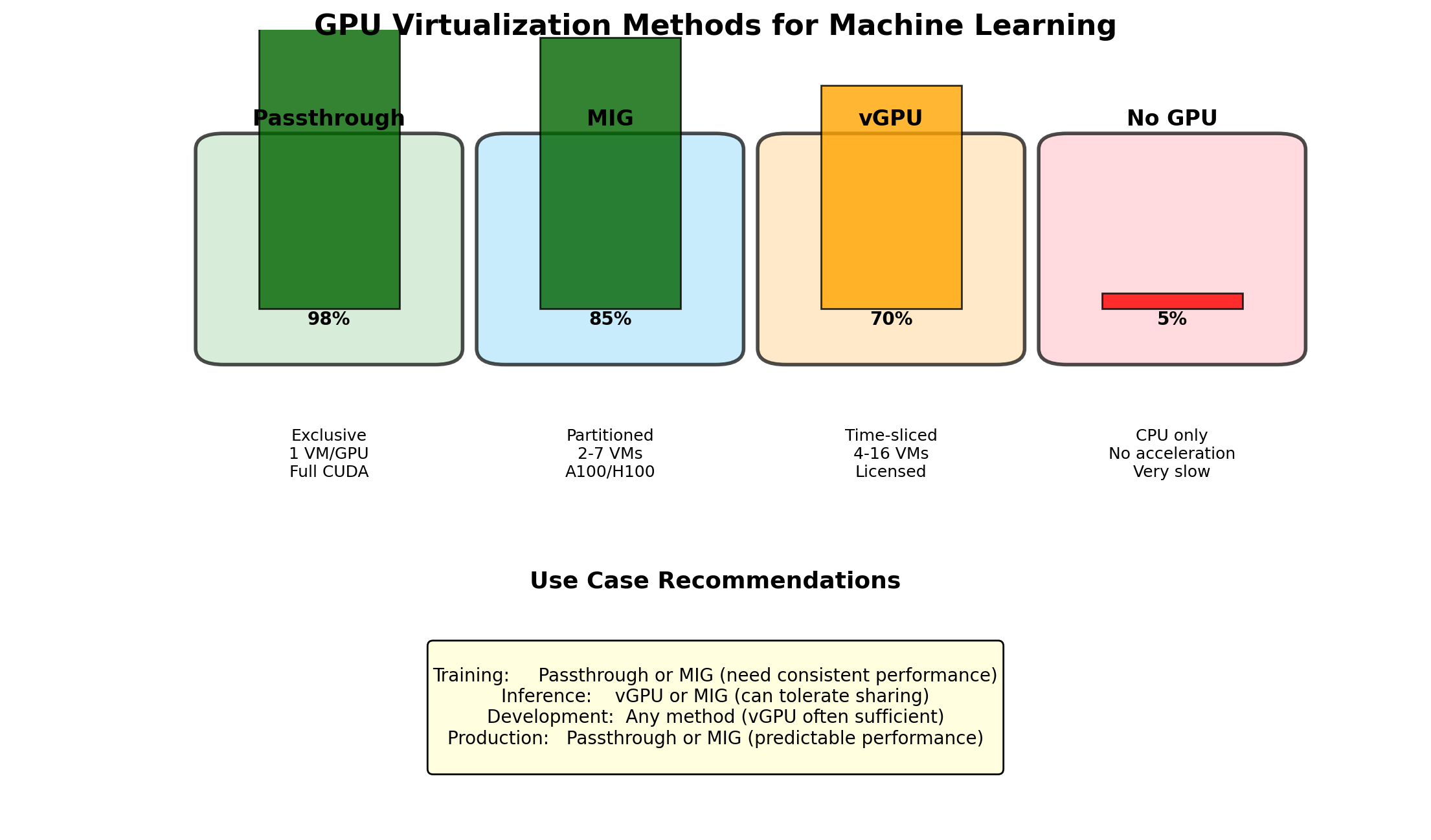

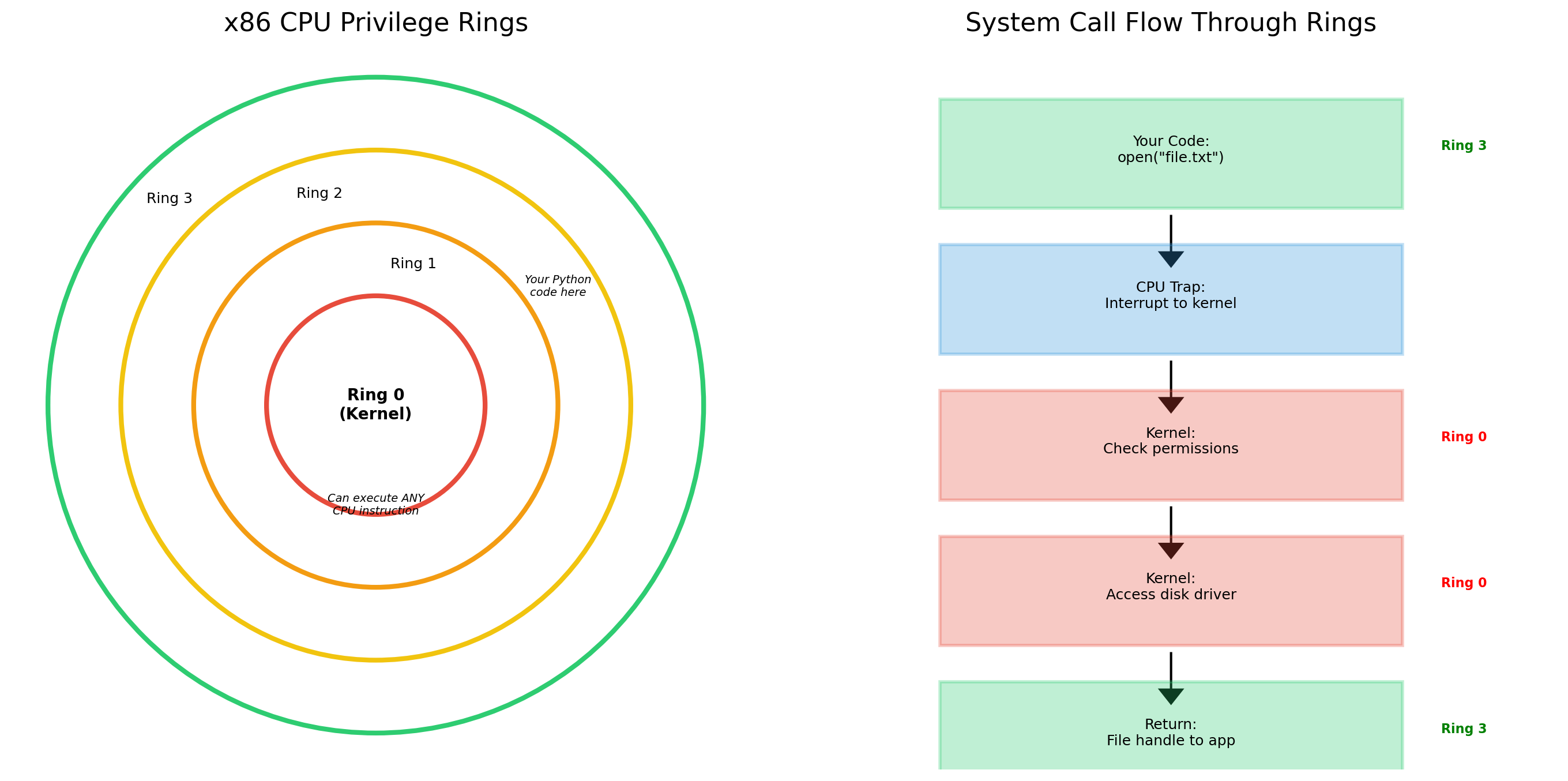

CPU Virtualization

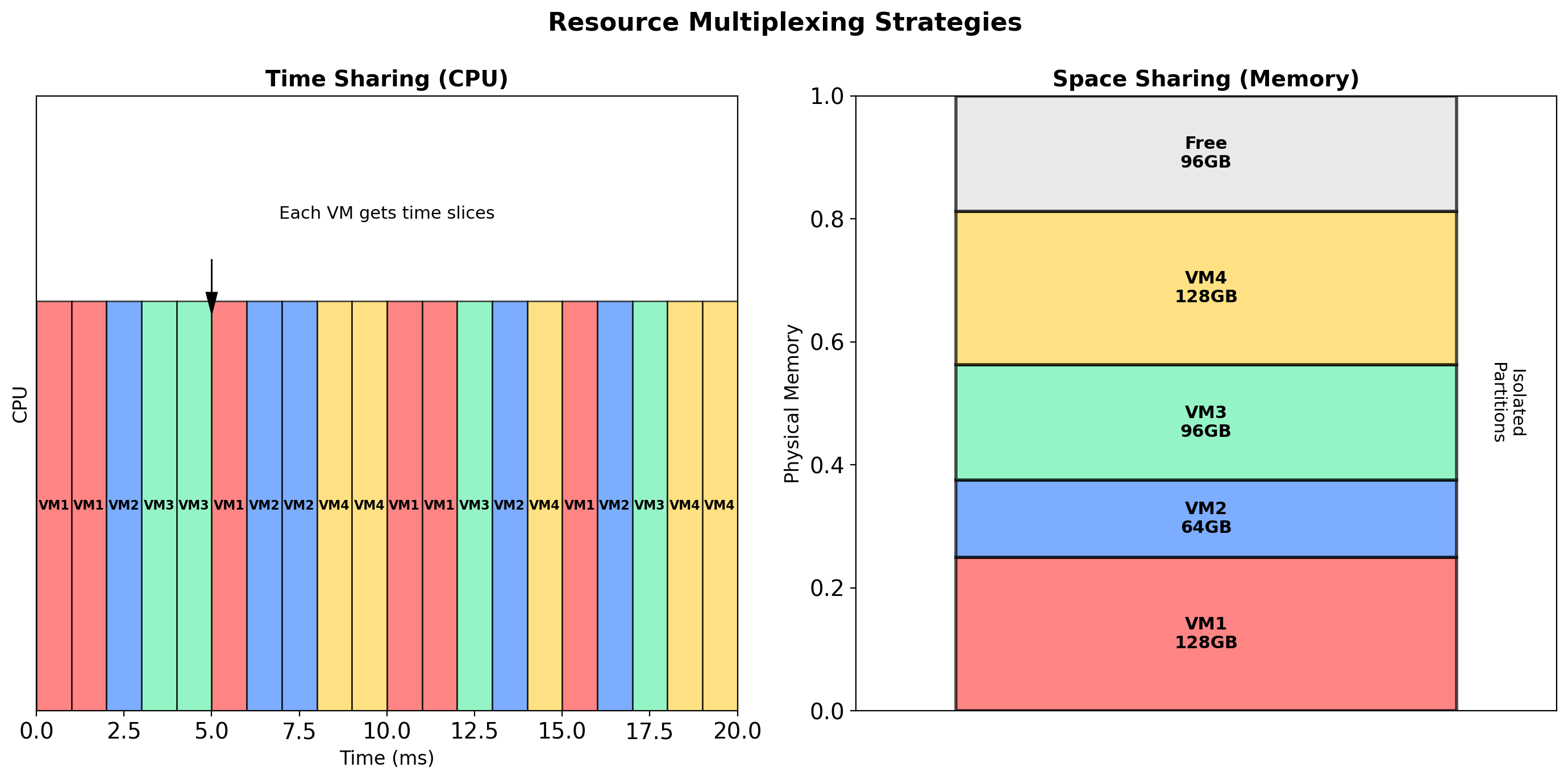

Each VM has virtual CPUs (vCPUs). The hypervisor schedules vCPUs onto physical cores.

Time-slicing

With more vCPUs than physical cores, the hypervisor switches between VMs. Each VM gets a fraction of CPU time.

Hardware support

Modern CPUs include virtualization extensions (Intel VT-x, AMD-V). These allow the hypervisor to run guest OS code at near-native speed.

Without hardware support, the hypervisor must trap and emulate privileged instructions—significantly slower.

Overcommit

A 16-core server can run VMs with a total of 32+ vCPUs. Works if VMs aren’t all CPU-bound simultaneously.

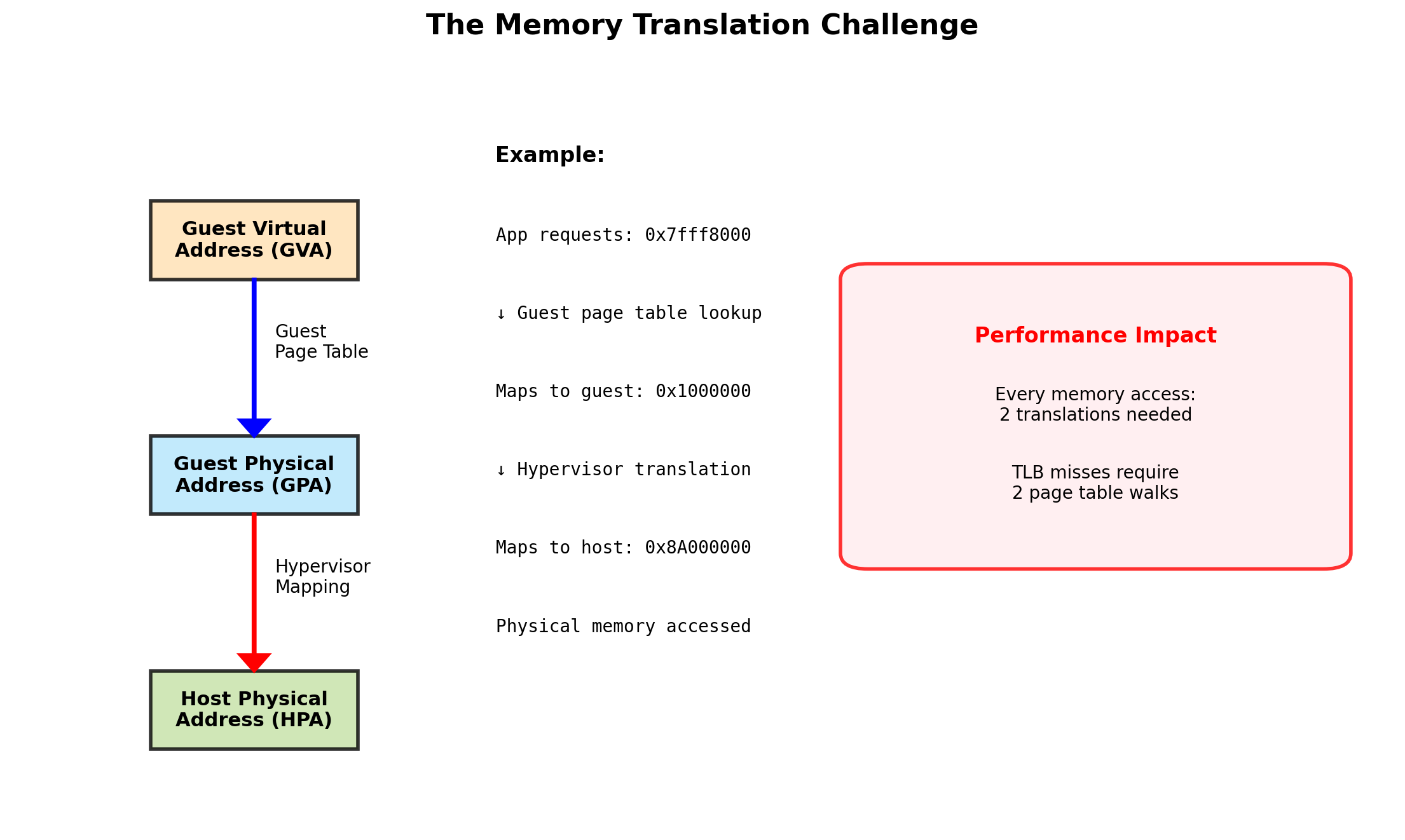

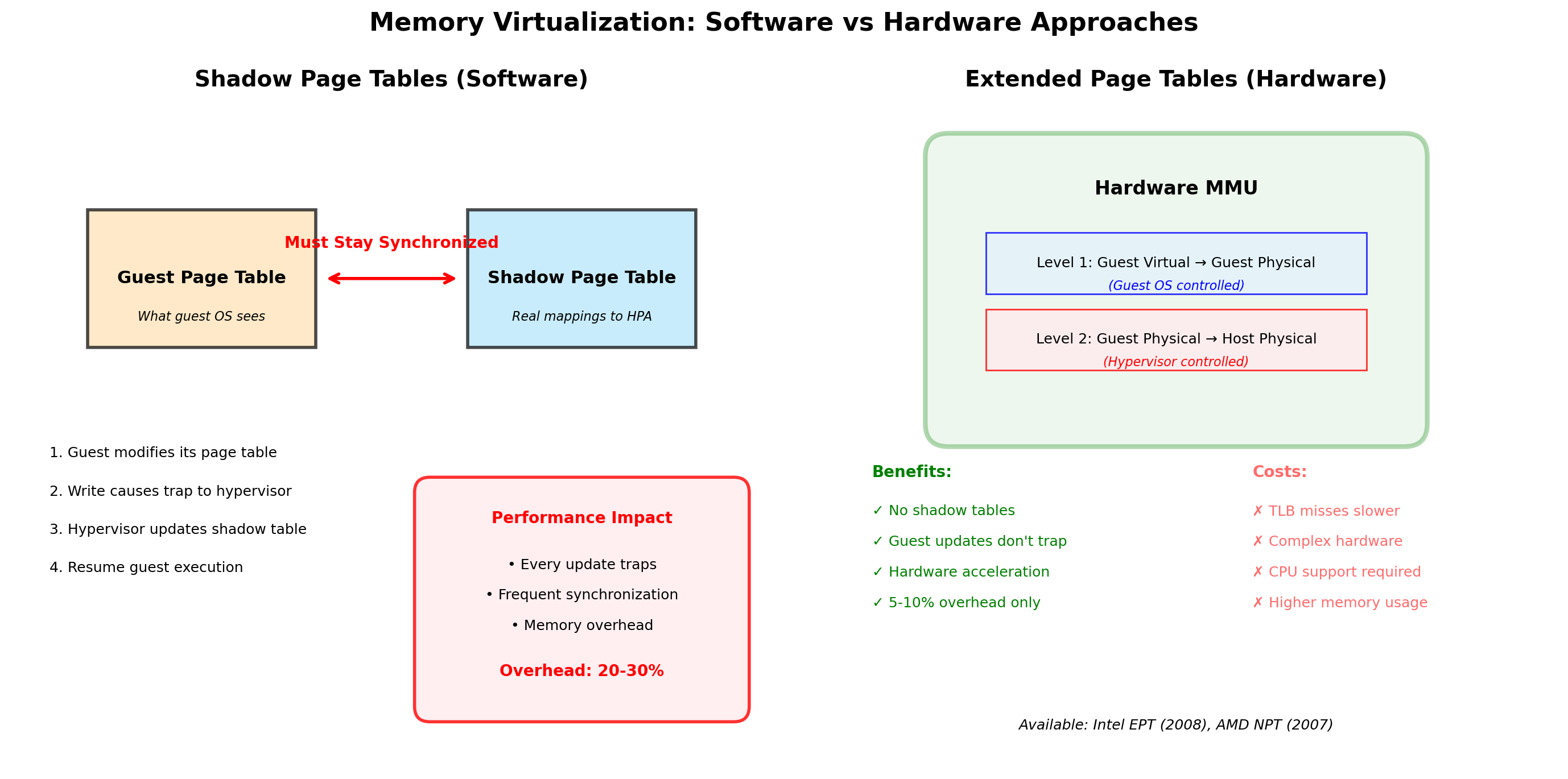

Memory Virtualization

Each VM sees contiguous physical memory starting at address 0. But the actual physical memory is elsewhere.

Two levels of translation

- Guest virtual → Guest physical (guest OS page tables)

- Guest physical → Host physical (hypervisor)

Hardware support (EPT/NPT)

Extended Page Tables (Intel) and Nested Page Tables (AMD) perform both translations in hardware. Without this, the hypervisor must intercept every memory access—extremely slow.

Isolation

VM 1’s guest physical address 0x1000 maps to a different host physical address than VM 2’s 0x1000. Neither can access the other’s memory. The CPU enforces this.

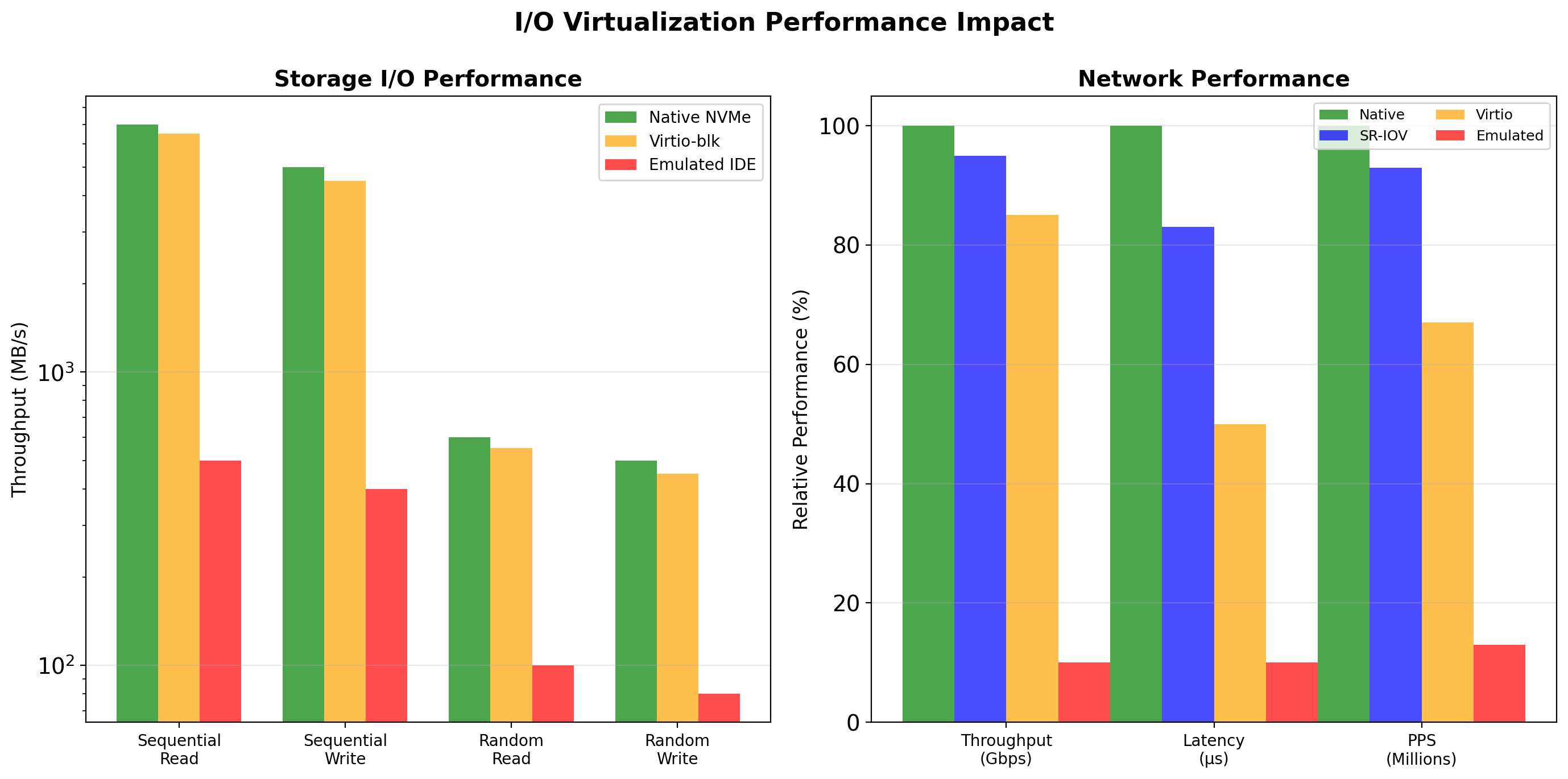

Storage and Network Virtualization

Virtual disks

Each VM sees disk devices (e.g., /dev/sda). These map to files on the host or raw disk partitions.

- VMDK, VHD, QCOW2 formats

- Thin provisioning: allocate space as used

- Snapshots: point-in-time copies

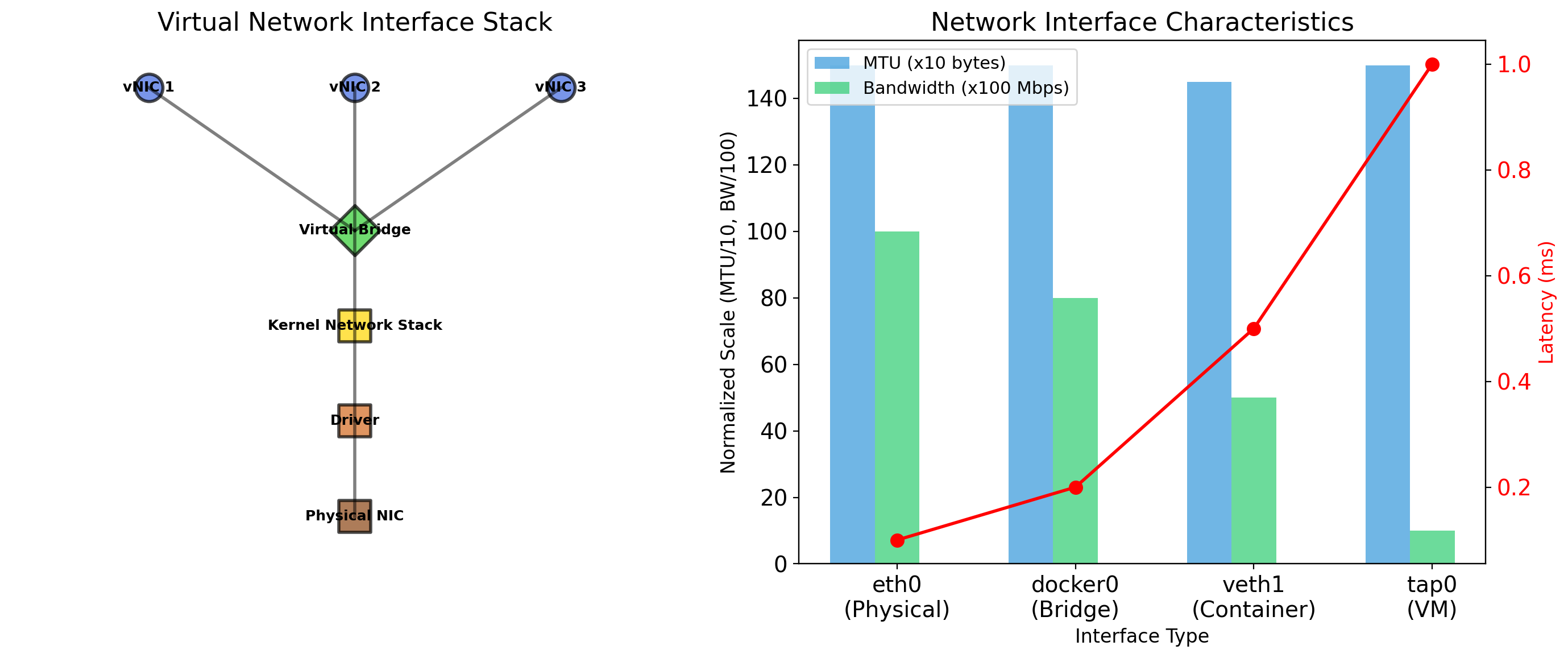

Virtual network interfaces

Each VM has virtual NICs. The hypervisor connects these to:

- Virtual switch — VMs communicate with each other

- Bridge — VMs appear on the physical network

- NAT — VMs share host’s IP for outbound traffic

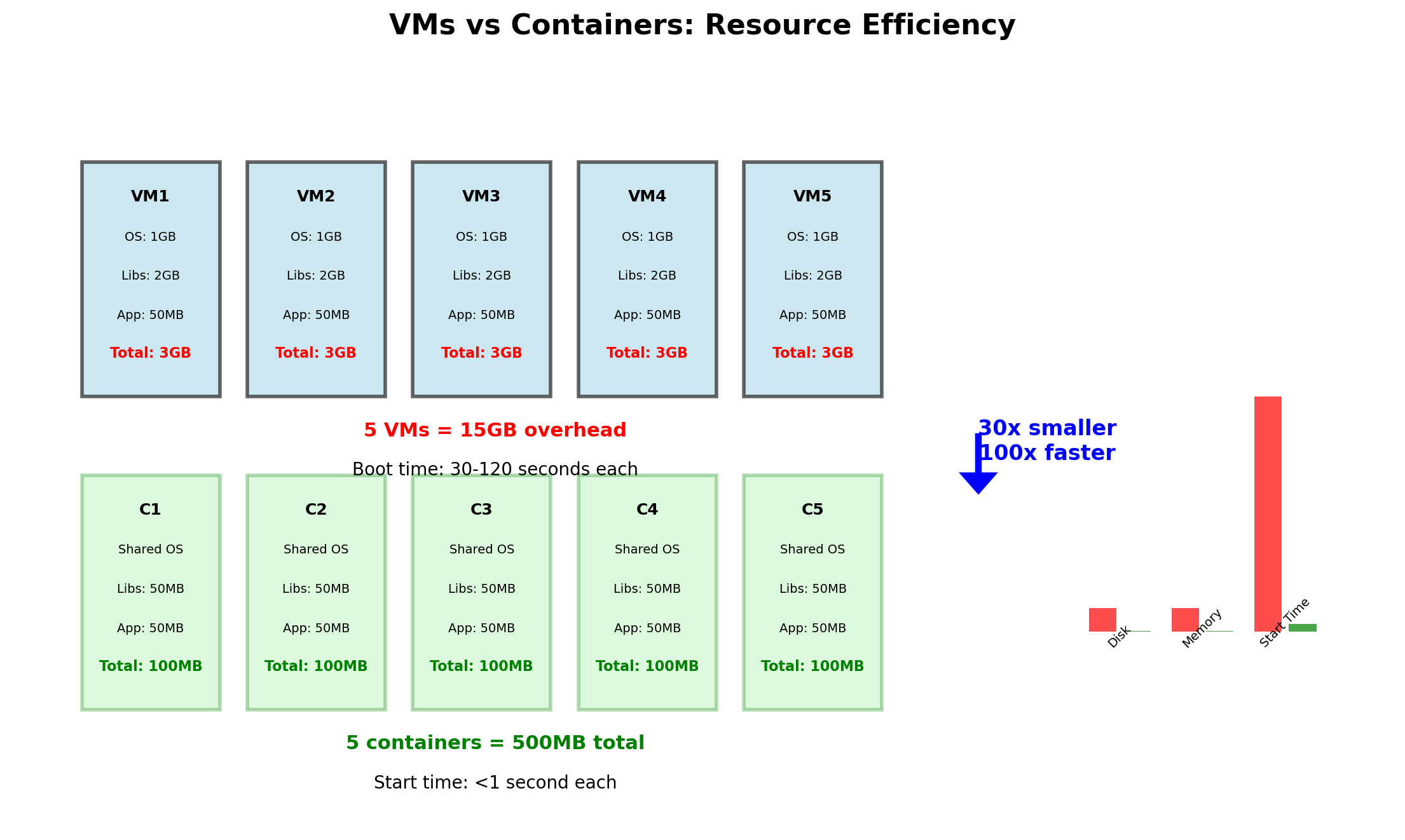

VM Overhead is Substantial

Each VM runs a complete operating system. This has costs:

| Resource | Per-VM Overhead |

|---|---|

| Memory | 512 MB - 2 GB for OS |

| Disk | 5 - 20 GB for OS install |

| Boot time | 30 seconds - 2 minutes |

| CPU | Hypervisor scheduling overhead |

10 VMs on a 256 GB server

- 10-20 GB consumed by OS memory

- 50-200 GB disk for OS installations

- 5-20 minutes total boot time

This overhead doesn’t do useful work. It’s the cost of isolation.

VMs Provide Strong Isolation

Despite the overhead, VMs remain valuable:

Security boundaries

VMs have separate kernels. A kernel exploit in VM1 does not compromise VM2. Cloud providers rely on this for multi-tenant isolation.

Different operating systems

Run Windows alongside Linux. Run legacy OS versions that applications depend on.

Hardware-enforced separation

CPU and memory isolation enforced by hardware, not just software. A malicious VM cannot escape without exploiting the hypervisor or CPU itself.

Where VMs are used

- Cloud compute — EC2 instances are VMs

- Multi-tenant hosting — Untrusted workloads isolated

- Desktop virtualization — Test environments

- Legacy applications — Run old OS versions

The overhead is acceptable when strong isolation is required. For trusted workloads where efficiency matters more, there’s another approach.

Cloud Instances Are Virtual Machines

When you launch an EC2 instance, you’re creating a VM.

t3.medium specifies:

- 2 vCPUs

- 4 GB memory

- Burstable CPU credits

AWS runs a hypervisor (Nitro, based on KVM) on physical servers. Your instance is a VM on that hypervisor, alongside other customers’ VMs.

You don’t see the hypervisor. You see a complete machine with the resources you requested.

Containers

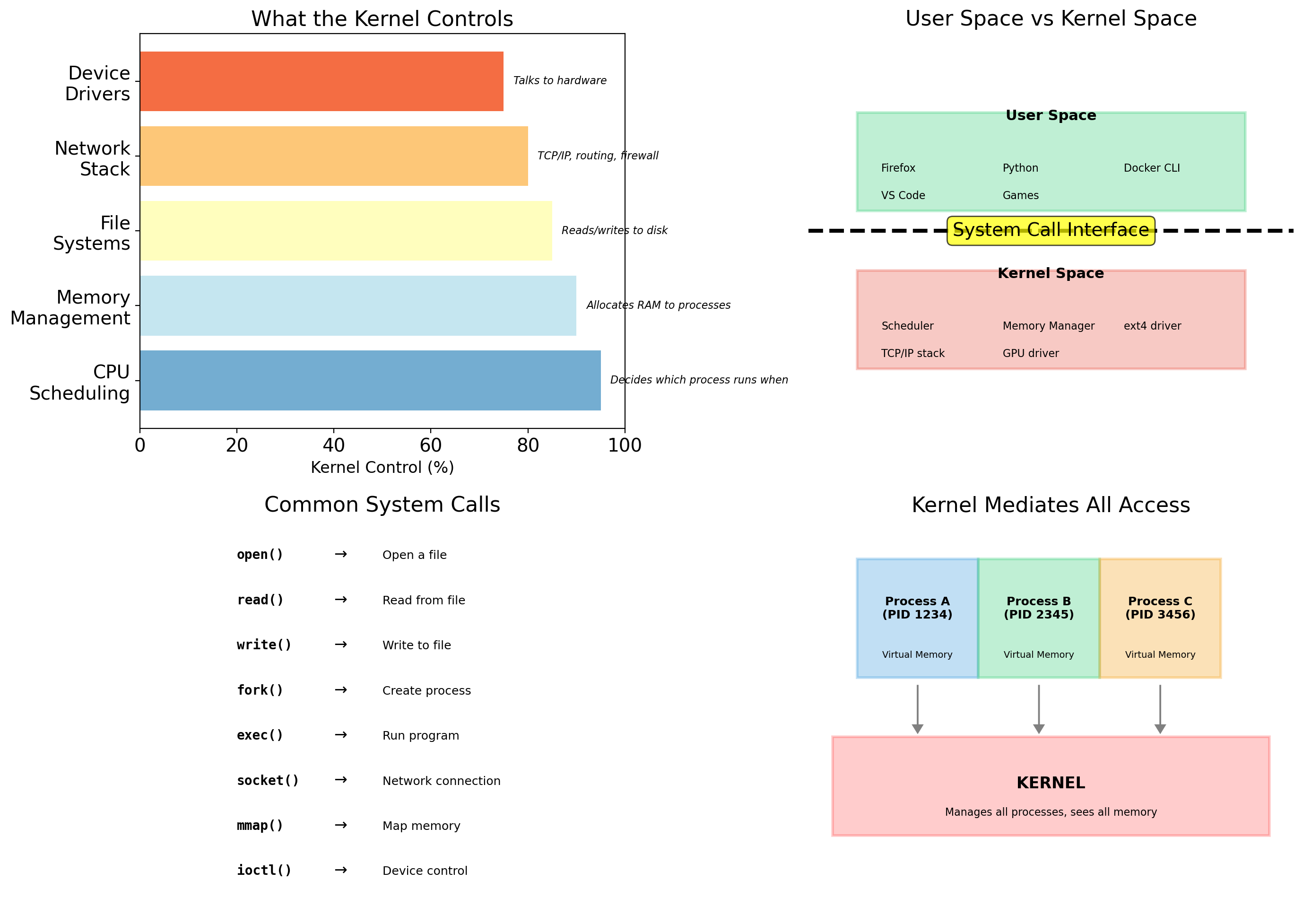

The Operating System Kernel

The kernel is the core of the operating system. It runs with full hardware privileges and manages:

Hardware access

CPU scheduling, memory allocation, disk I/O, network interfaces. Applications cannot touch hardware directly—they ask the kernel.

Process management

Starting, stopping, scheduling processes. Deciding which process runs on which CPU core.

Resource allocation

Which process gets how much memory. Which can access which files. Which can open network connections.

The kernel is the boundary between software and hardware. Everything else runs “on top of” the kernel.

Processes Request Resources Through System Calls

When your application needs to:

- Open a file

- Allocate memory

- Send network data

- Start another process

It makes a system call to the kernel. The kernel validates the request, performs the operation, and returns the result.

# Your code

f = open('/data/users.json', 'r')

# What actually happens:

# 1. Python calls open()

# 2. open() makes syscall to kernel

# 3. Kernel checks permissions

# 4. Kernel opens file, returns handle

# 5. Your code gets file objectThe application never touches the disk directly. The kernel mediates all access.

The Kernel Sees All Processes and Resources

On a normal Linux system, the kernel maintains:

One process table

Every process has an entry. Each can see other processes with ps aux.

One filesystem tree

Starting at /. All processes see the same files (subject to permissions).

One network stack

Shared IP addresses, ports, routing tables.

One set of users

UID 1000 is the same user for all processes.

When you run multiple applications, they all share these views. Process A can see process B. Both see the same /tmp. Both compete for the same ports.

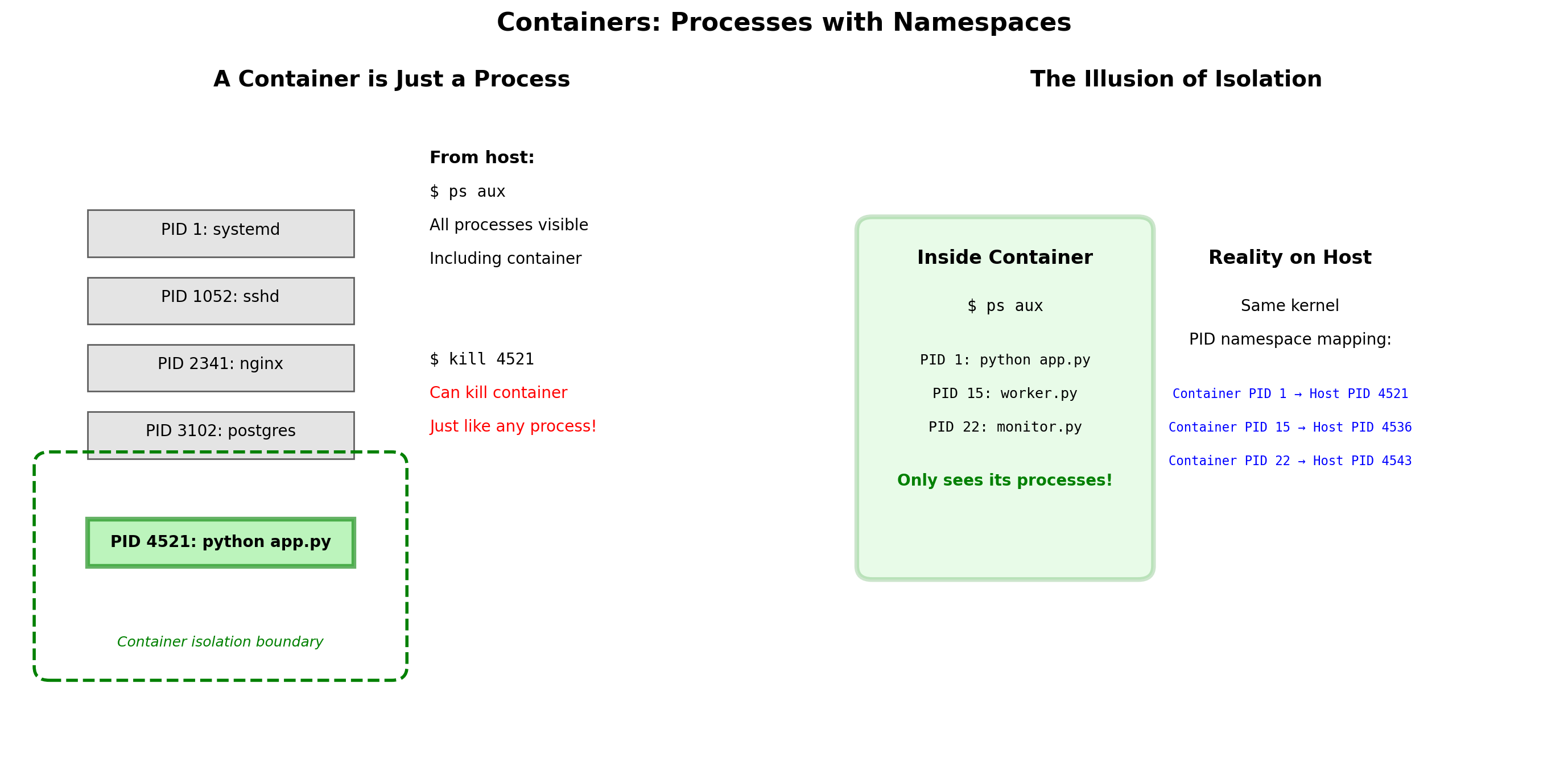

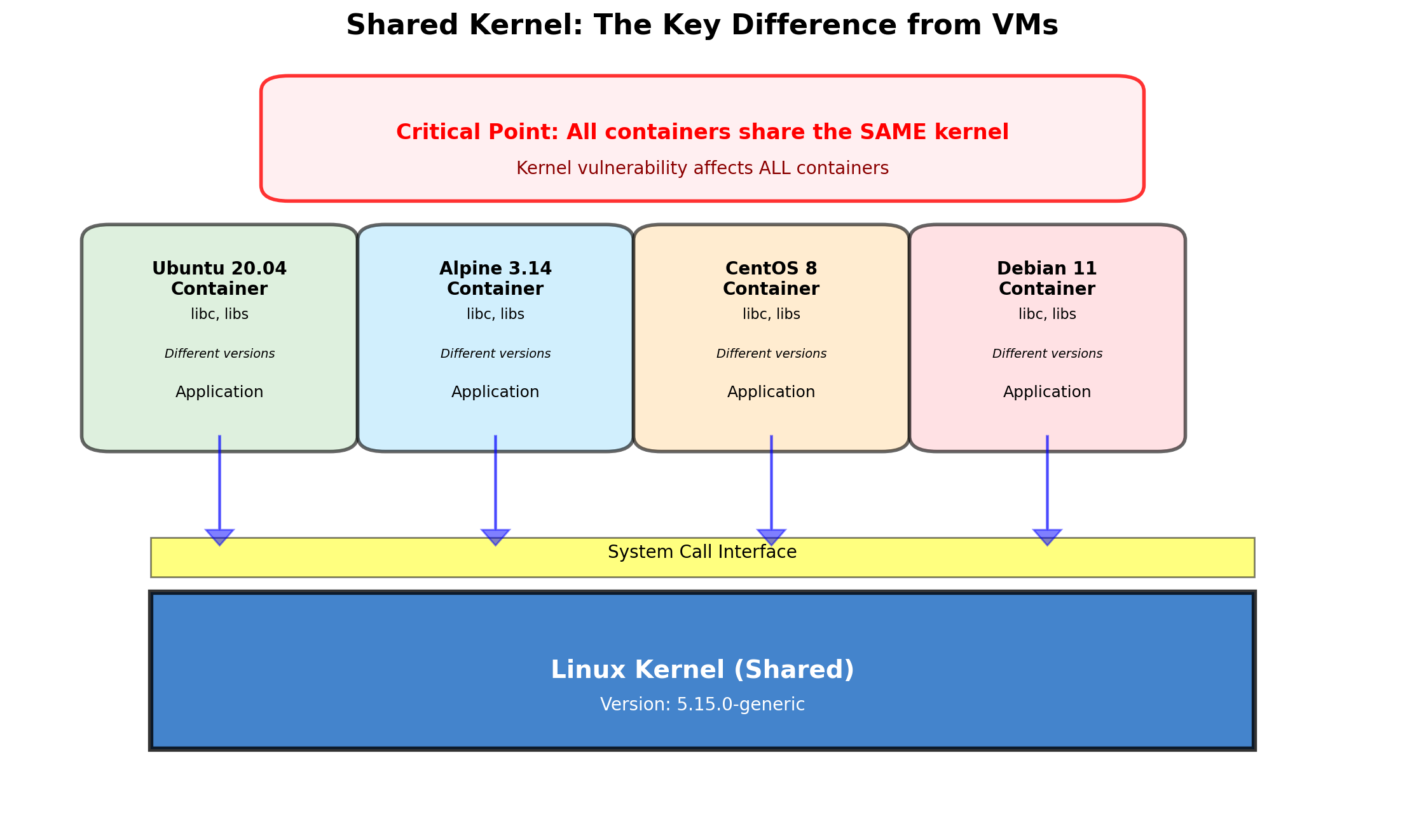

Containers: Processes with Restricted Kernel Views

A container is not a virtual machine. It does not run a separate kernel.

A container is a process (or group of processes) that the kernel treats specially. When a containerized process asks “what processes exist?”, the kernel returns a filtered answer.

The kernel provides namespaces—separate views of system resources. A process in a namespace sees only what that namespace contains.

Same kernel. Different perspectives.

The containerized process believes it’s alone on the system. It sees only its own processes, its own filesystem, its own network stack. The kernel maintains this illusion.

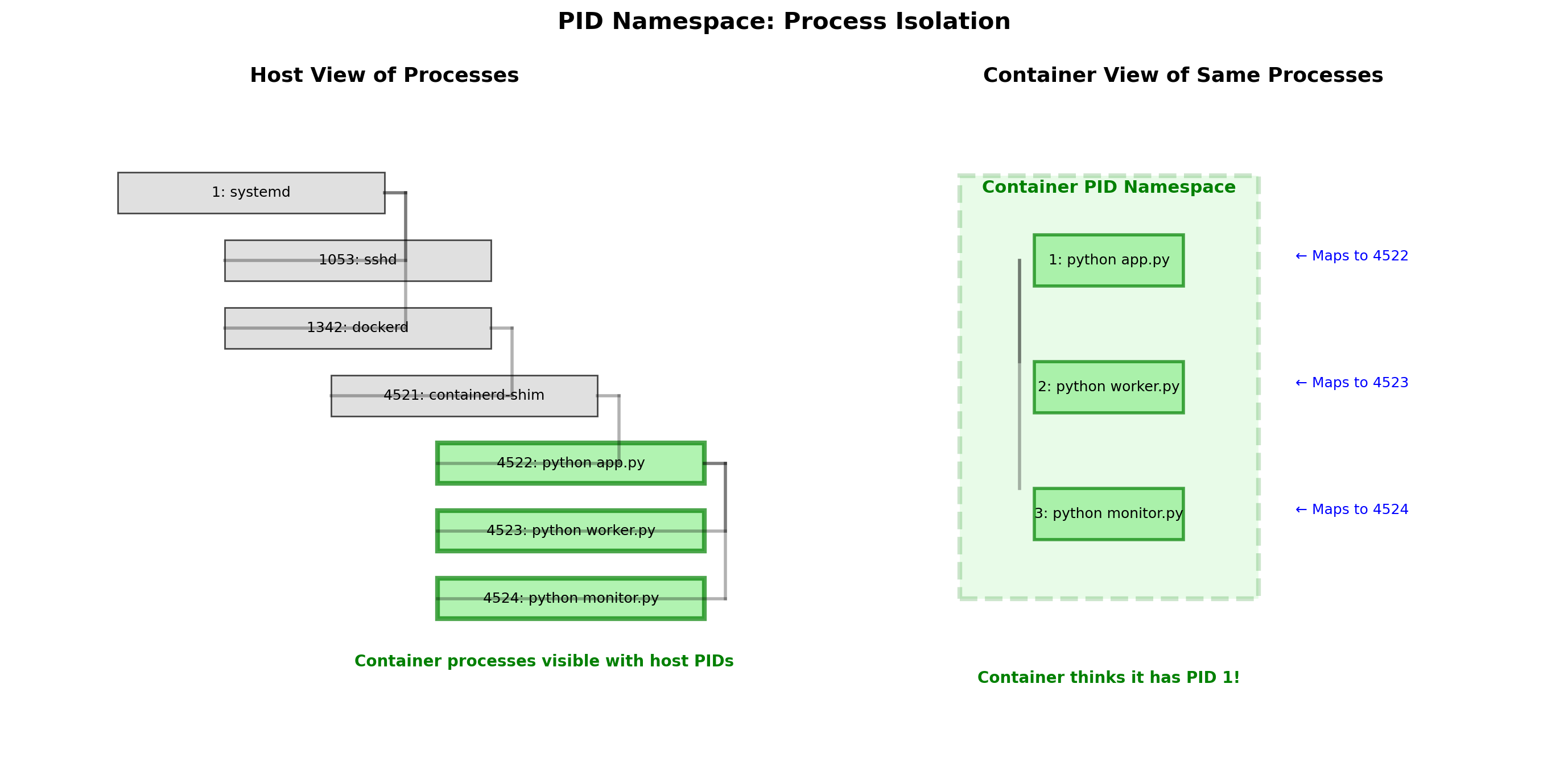

PID Namespace: Isolated Process Trees

Each container has its own process ID namespace.

Inside the container:

The main process is PID 1. Child processes are PID 2, 3, etc. The container sees only its own processes.

On the host:

The same processes have different PIDs. Container A’s PID 1 might be host PID 4523.

# Inside container

$ ps aux

PID COMMAND

1 /app/server

2 /app/worker

# On host

$ ps aux | grep app

4523 /app/server # Container A's PID 1

4524 /app/worker # Container A's PID 2Container A cannot see or signal Container B’s processes. They exist in separate PID namespaces.

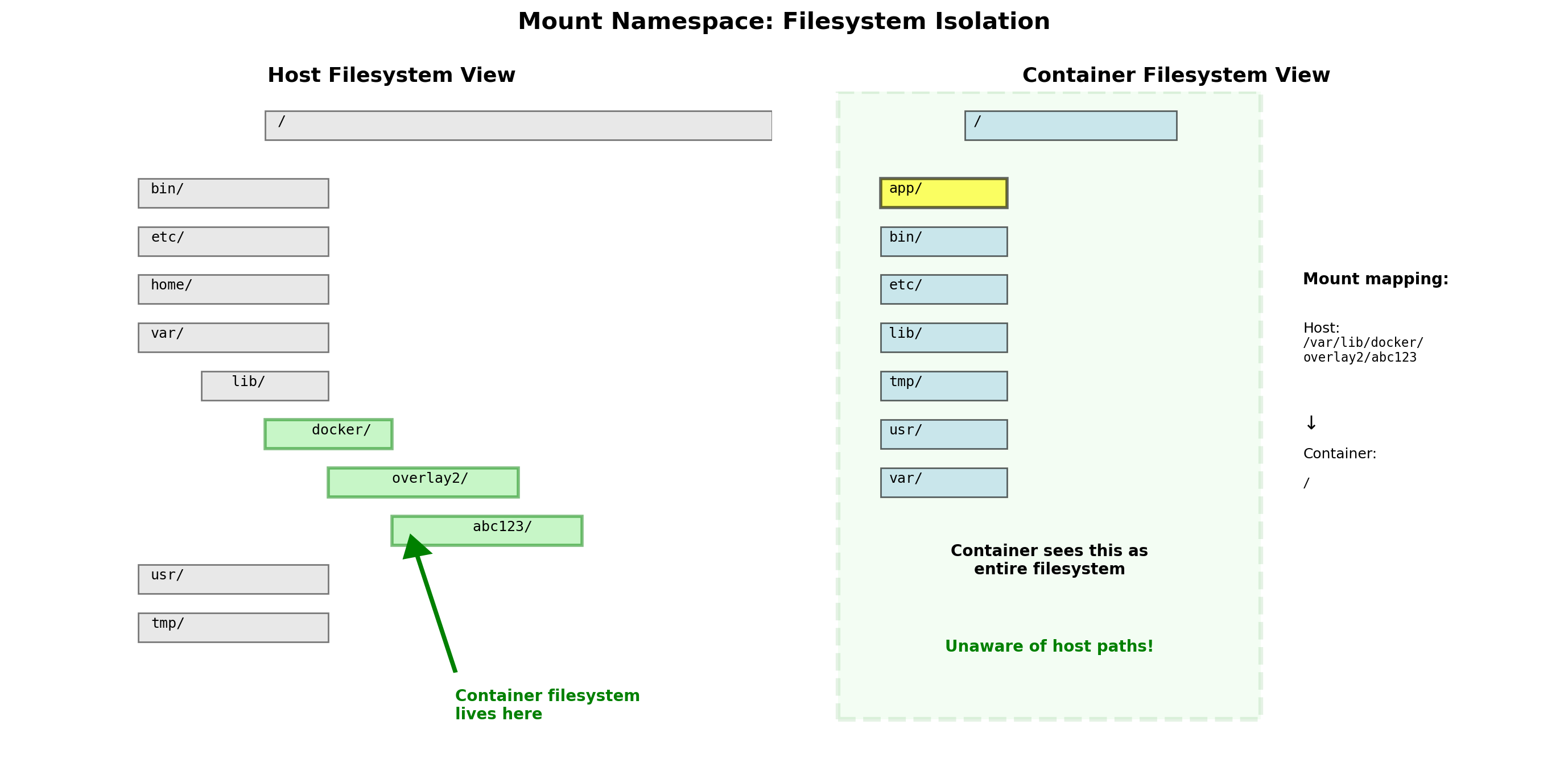

Mount Namespace: Isolated Filesystem Views

Each container has its own mount namespace—a separate view of the filesystem.

Container sees its own root

The container’s / is not the host’s /. It’s a separate directory tree, typically from a container image.

# Container A

$ ls /

bin etc home lib usr app

# Container B (different image)

$ ls /

bin etc lib64 opt usr data

# Host

$ ls /

bin boot dev etc home lib ...Container A cannot see Container B’s files. Neither can see arbitrary host files. The kernel enforces this separation.

Host directories can be explicitly mounted into containers when needed—but the default is isolation.

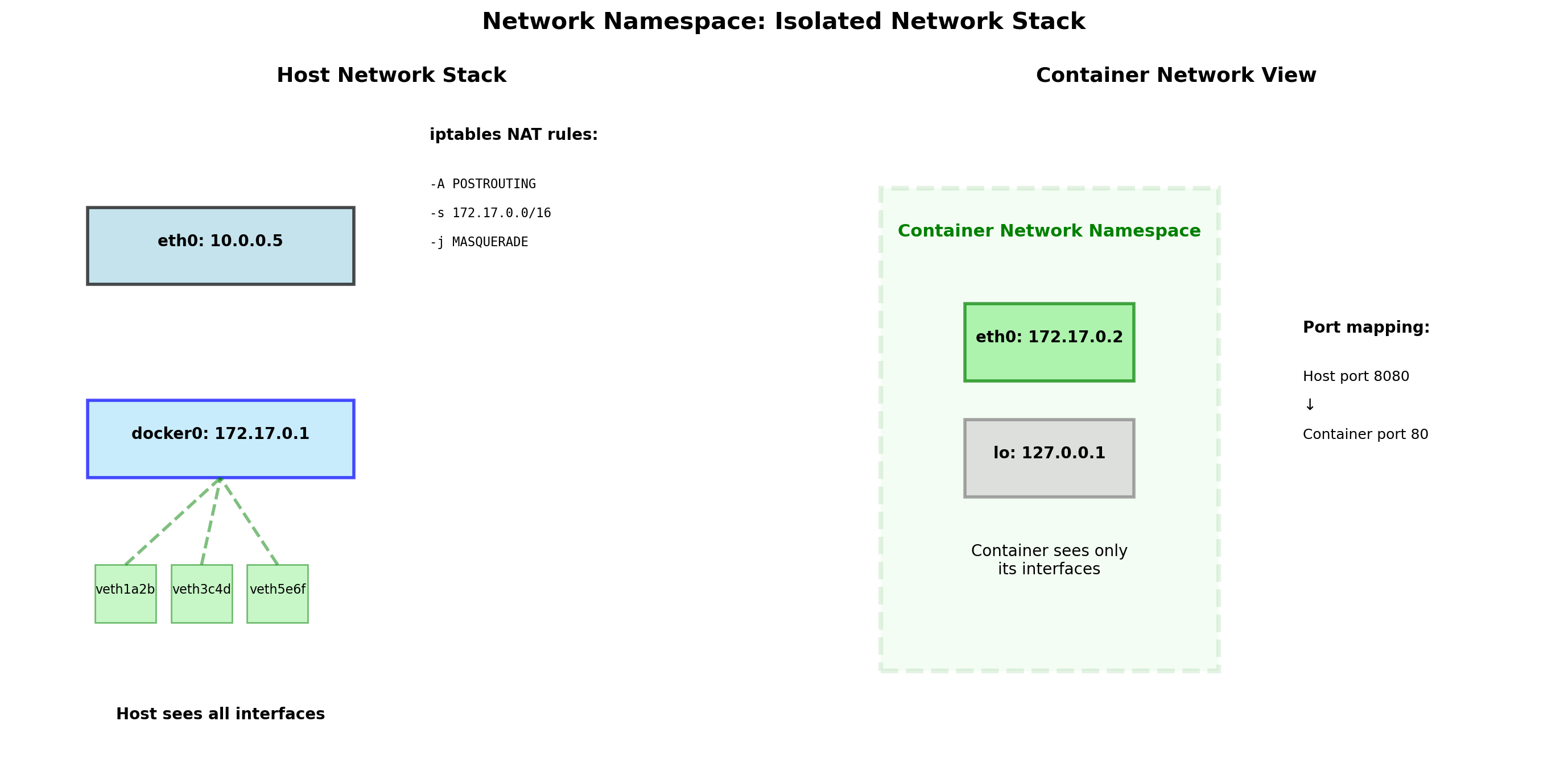

Network Namespace: Isolated Network Stacks

Each container has its own network namespace:

- Own network interfaces

- Own IP addresses

- Own routing tables

- Own port space

Port conflicts eliminated

Container A listens on port 80. Container B also listens on port 80. No conflict—each has its own port namespace.

# Container A

$ ip addr

eth0: 172.17.0.2/16

# Container B

$ ip addr

eth0: 172.17.0.3/16

# Both listen on :80, no conflictThe host bridges container networks to the physical network. Containers can communicate with each other and the outside world through this bridge.

Other Namespaces

Linux provides several namespace types. Containers typically use all of them:

| Namespace | Isolates |

|---|---|

| PID | Process IDs—container sees own process tree |

| Mount | Filesystem—container sees own root and mounts |

| Network | Network stack—own interfaces, IPs, ports |

| UTS | Hostname—container can have its own hostname |

| IPC | Inter-process communication—shared memory, semaphores |

| User | User/group IDs—UID 0 in container can map to non-root on host |

Each namespace creates an isolated view of one resource type. Combined, they create the illusion of a separate machine.

The kernel tracks which namespace each process belongs to. System calls return results filtered through the process’s namespaces.

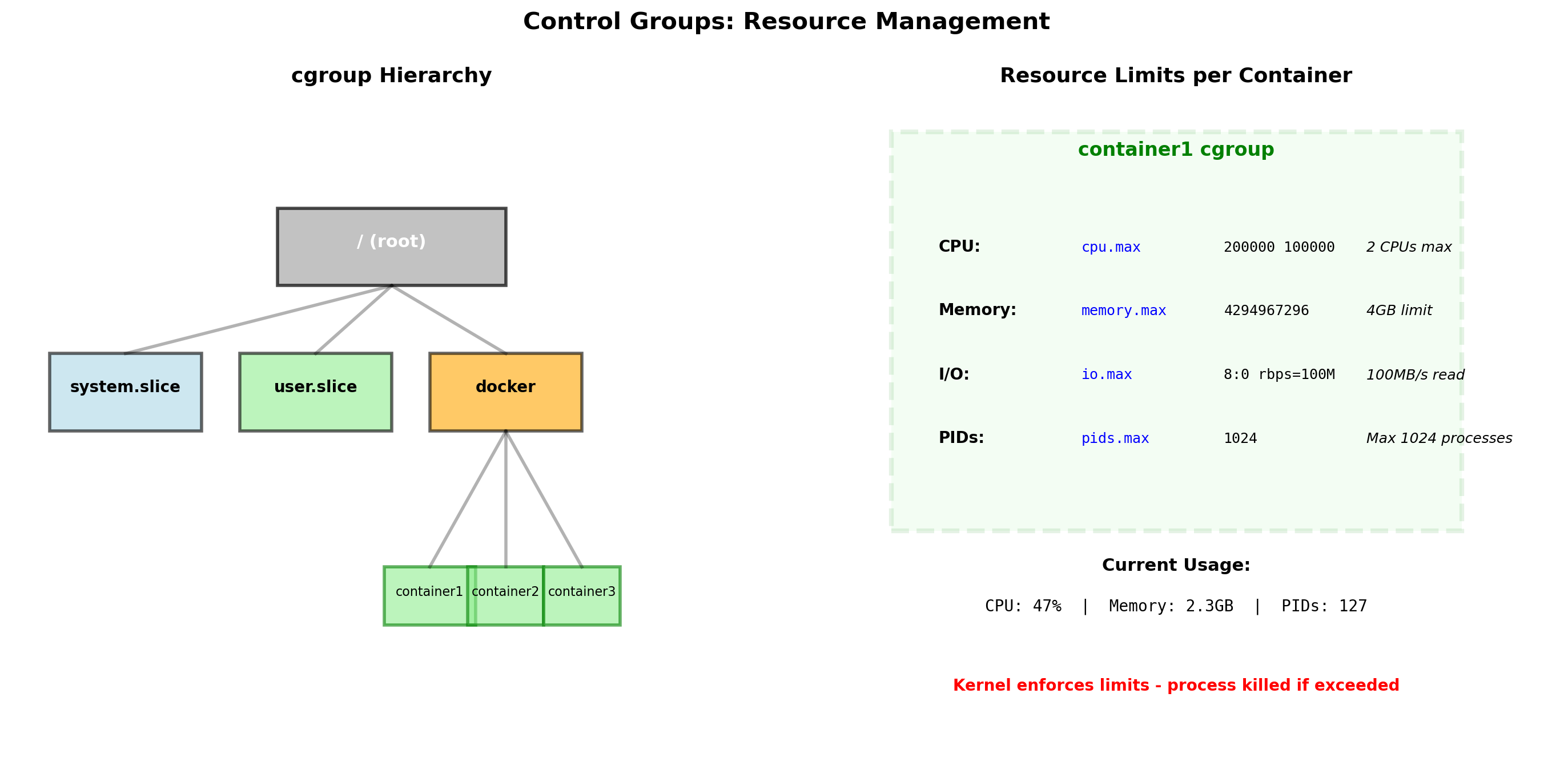

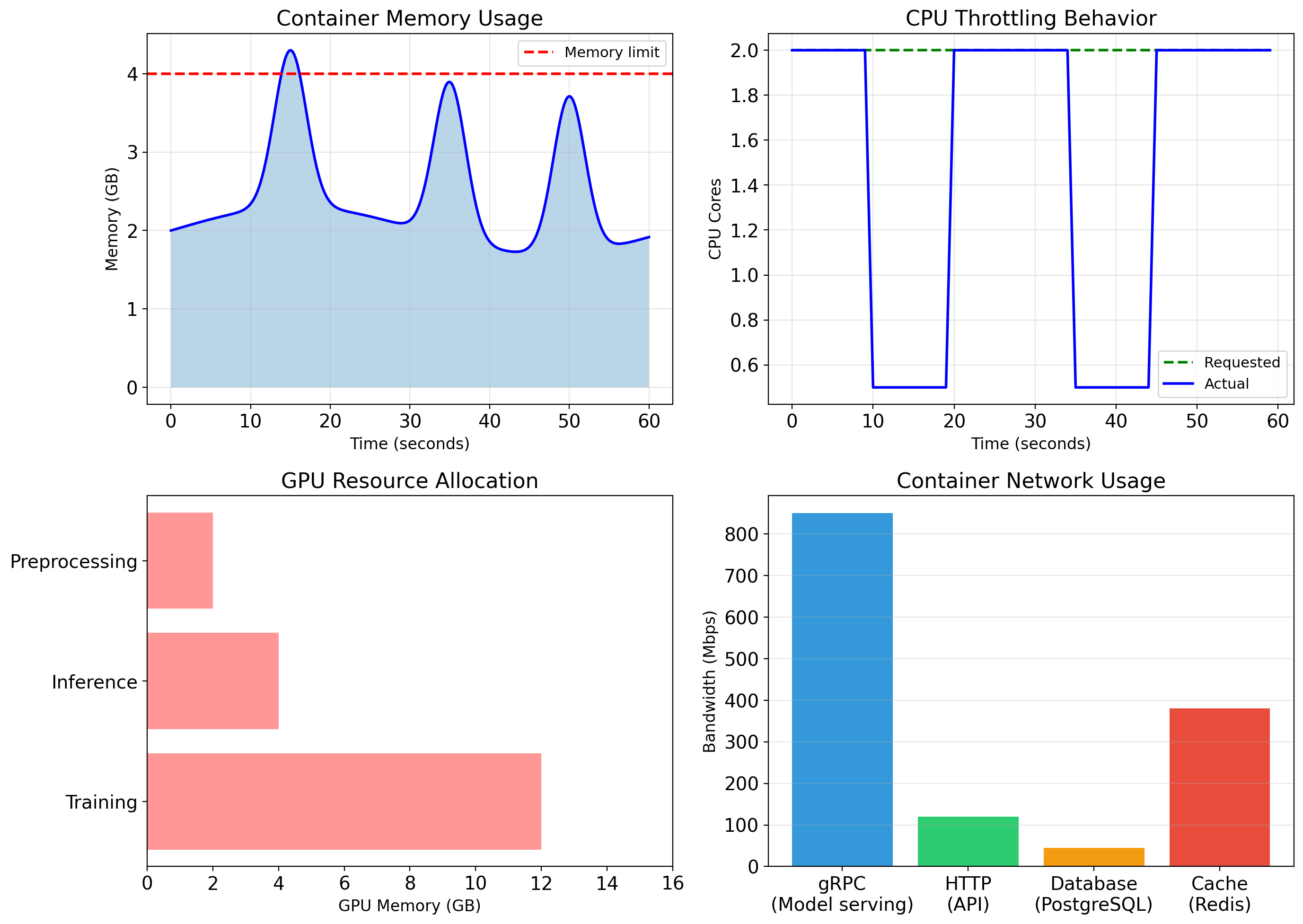

Cgroups Limit Resource Consumption

Namespaces provide isolation—processes can’t see each other. But they don’t prevent resource exhaustion.

Without limits, one container could:

- Consume all available CPU

- Exhaust system memory

- Saturate disk I/O

Control groups (cgroups) let the kernel limit resources per container.

If the container exceeds its memory limit, the kernel kills processes inside that container—not processes in other containers or on the host.

Container Resource Limits in Practice

CPU limits

Restrict container to fraction of CPU time or specific cores.

# Max 1.5 CPUs worth of time

docker run --cpus=1.5 myapp

# Pin to cores 0 and 1

docker run --cpuset-cpus=0,1 myappMemory limits

Hard cap on memory usage. Exceeding triggers OOM killer inside container.

Why limits matter

A memory leak in one container doesn’t exhaust host memory. A busy loop in one container doesn’t starve others.

Limits enable density—many containers on one host—without mutual interference.

Overhead

Cgroup accounting has minimal overhead. The kernel already tracks resource usage per process; cgroups aggregate and enforce limits.

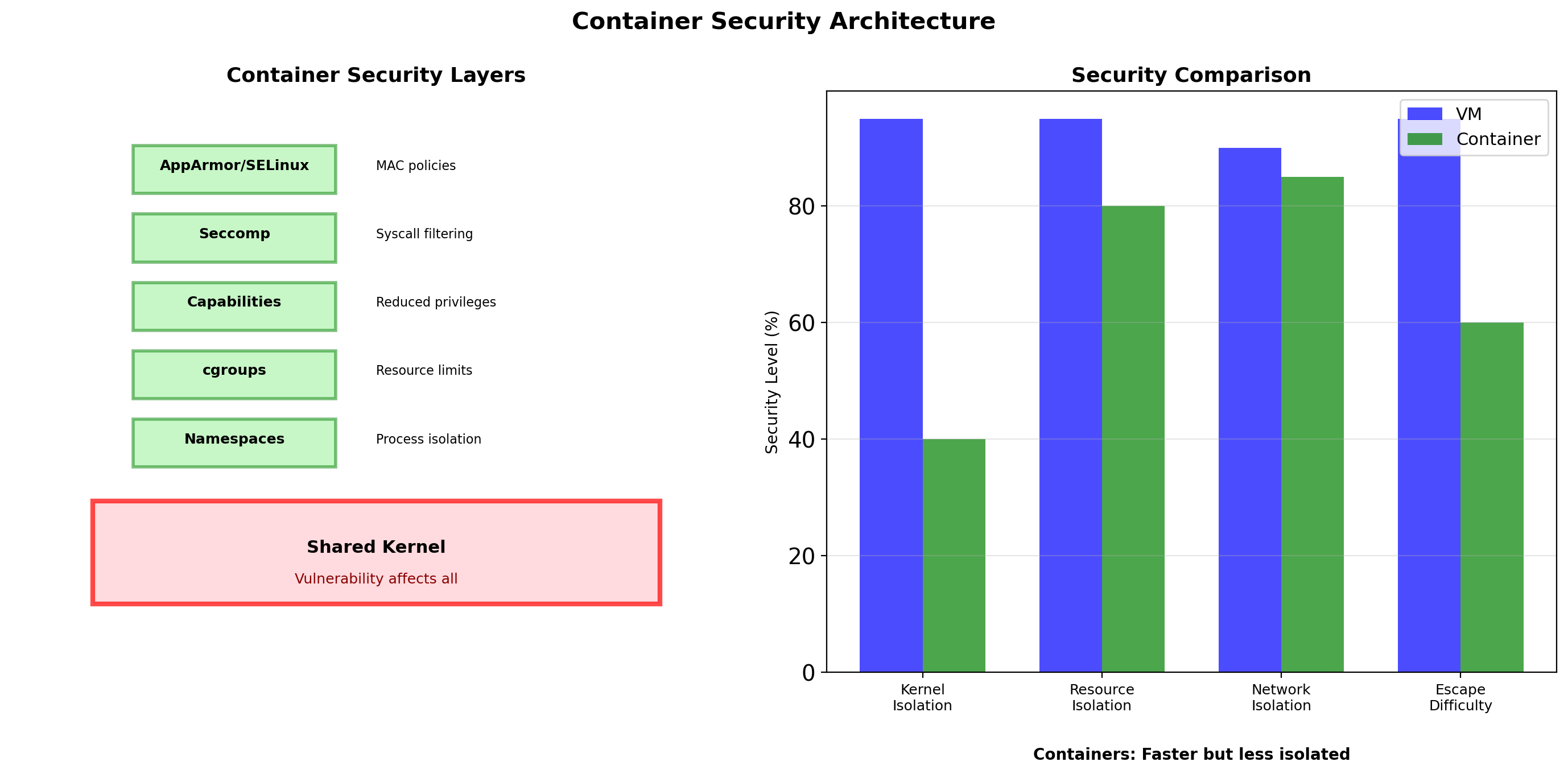

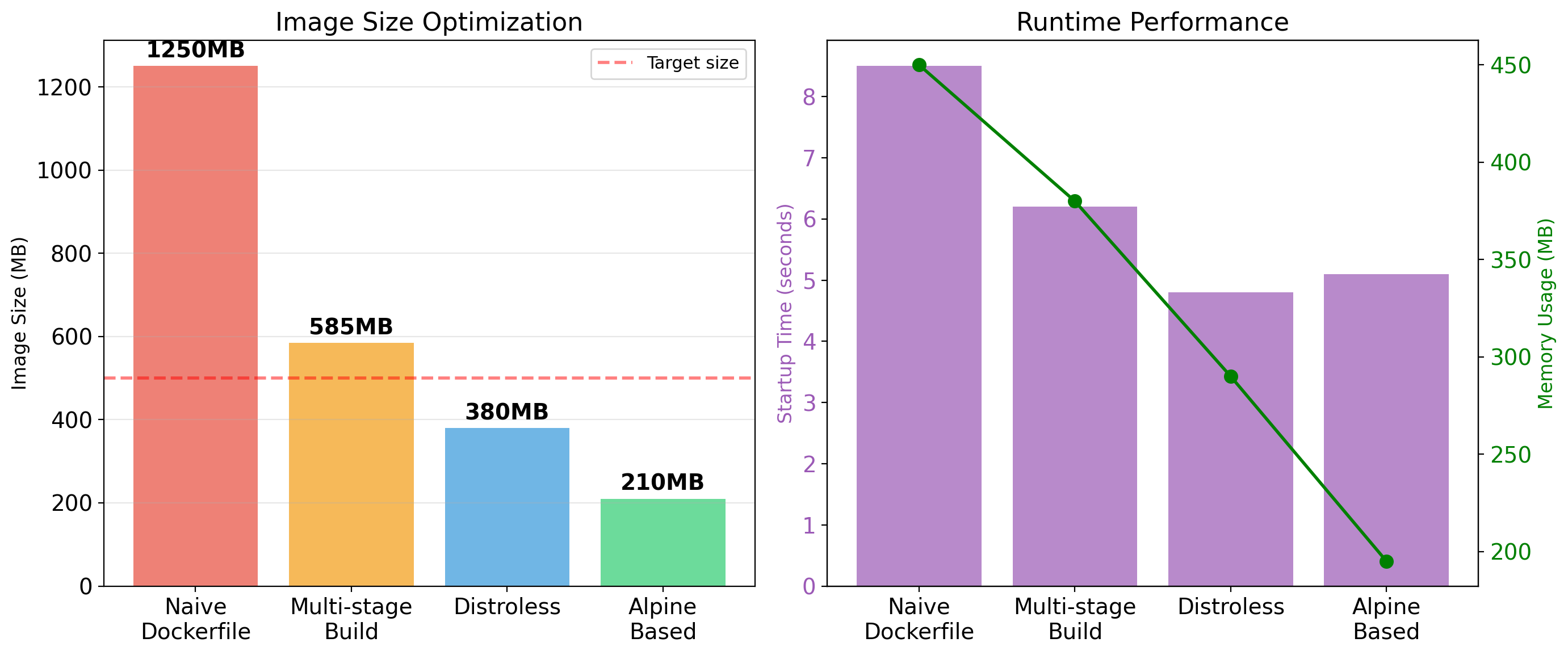

Containers vs VMs: Different Isolation Mechanisms

VMs run separate kernels. Containers share the host kernel.

VMs are isolated by hardware virtualization. Containers are isolated by kernel namespaces.

Shared Kernel: Implications

Efficiency gains

No duplicate kernels—memory savings of hundreds of MB per workload.

No OS boot—containers start in milliseconds.

No hypervisor overhead—near-native performance.

Higher density—dozens or hundreds of containers per host.

Compatibility constraint

Containers must be compatible with host kernel.

Linux containers need Linux kernel. Windows containers need Windows kernel.

Docker Desktop on Mac/Windows runs a Linux VM to host Linux containers.

Security boundary

Kernel bugs affect all containers. A kernel vulnerability could allow container escape.

Containers share kernel attack surface. VMs have separate kernels.

For mutually untrusting tenants (public cloud), VMs provide stronger isolation.

For trusted workloads (your own services), containers are typically sufficient.

Additional hardening possible: seccomp (syscall filtering), AppArmor/SELinux (mandatory access control), rootless containers.

Container Startup is Fast

VMs boot an operating system: kernel initialization, init system, service startup.

Containers start a process. The kernel is already running. The container runtime sets up namespaces and cgroups, then executes the application.

This speed difference enables different deployment patterns—containers can be started and stopped rapidly in response to demand.

Container Density is High

A server with 256 GB RAM running VMs:

| Component | Memory |

|---|---|

| Hypervisor | ~2 GB |

| Per-VM OS overhead | ~1-2 GB |

| Available for 10 VMs | ~236 GB |

| Per-VM for applications | ~20-23 GB |

Same server running containers:

| Component | Memory |

|---|---|

| Host OS | ~2 GB |

| Container runtime | ~200 MB |

| Available for containers | ~253 GB |

| Per-container overhead | ~10-50 MB |

Docker

Namespaces and Cgroups Existed Before Docker

The Linux kernel has provided namespaces since 2002 and cgroups since 2007. Containers were possible—but painful to use.

To create a container manually:

- Create namespace for PID, mount, network, etc.

- Set up a root filesystem

- Configure cgroup limits

- Set up networking (veth pairs, bridges)

- Handle DNS, hostname, users

- Actually run the application

Each step requires detailed knowledge of kernel interfaces. Different tools for each piece. No standard format for packaging.

Docker, released in 2013, made containers accessible. Not by inventing containers—by making them usable.

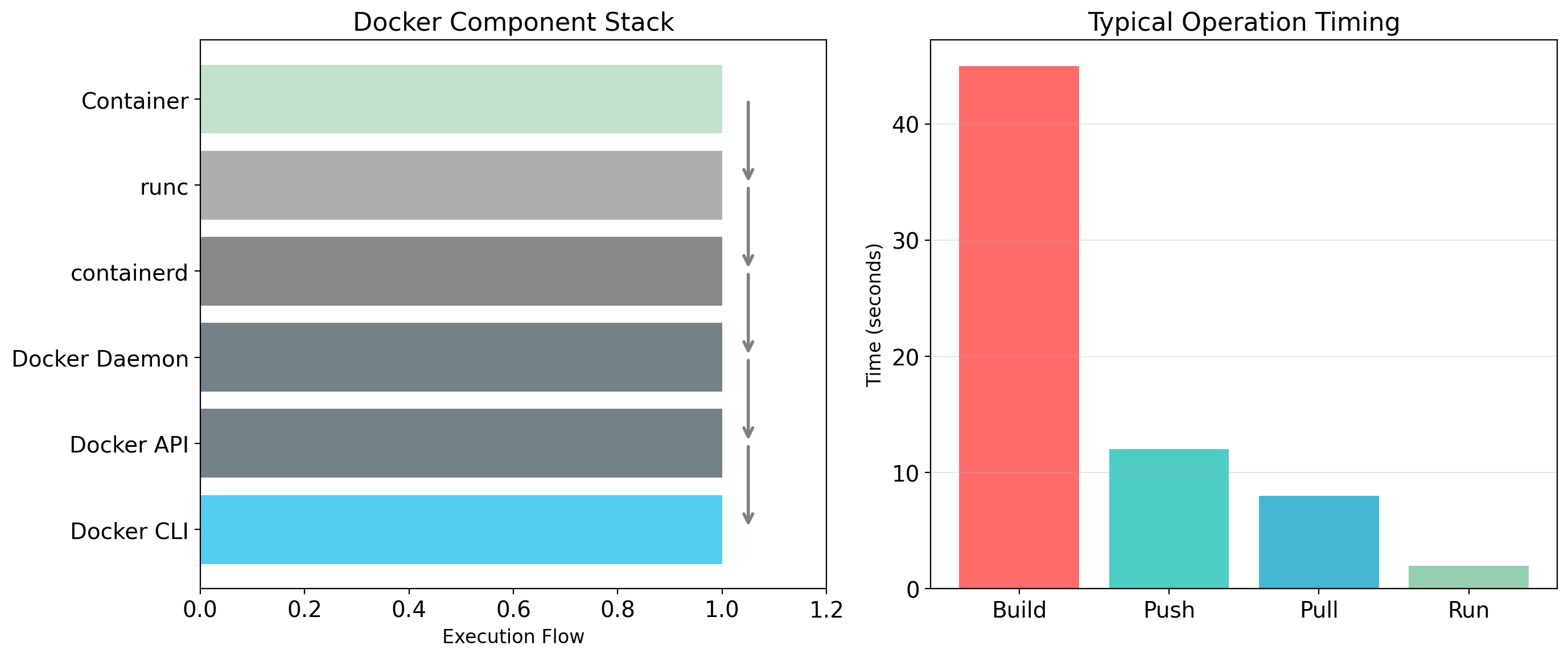

Docker Provides Tooling, Not Technology

Docker is a set of tools that make containers practical:

Image format

A standard way to package an application with its dependencies. Portable across machines running Docker.

Build system

Dockerfiles describe how to create images. Reproducible, automated builds.

Distribution

Registries store and serve images. Push images from one machine, pull to another.

Runtime

Commands to run, stop, inspect containers. Manages namespaces, cgroups, networking behind the scenes.

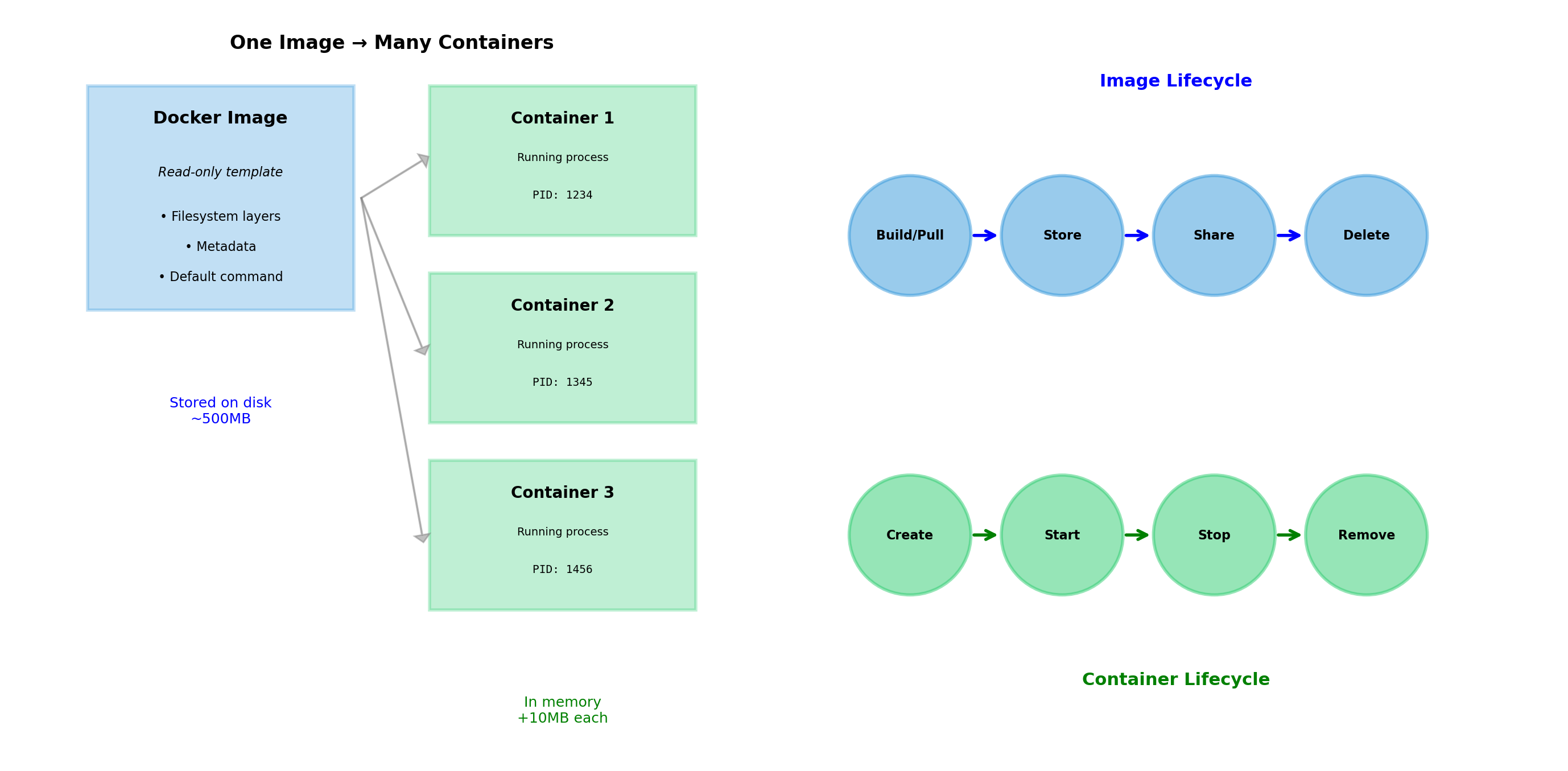

Images and Containers Are Different Things

Image

A read-only template. Contains:

- Filesystem contents (application code, libraries, config)

- Metadata (what command to run, environment variables)

Images are immutable. Once built, they don’t change.

Container

A running instance of an image. Has:

- The image’s filesystem (read-only)

- A writable layer for runtime changes

- Running processes

- Network interfaces

- State (running, stopped, etc.)

Many containers can run from the same image. Each has its own writable layer and process state.

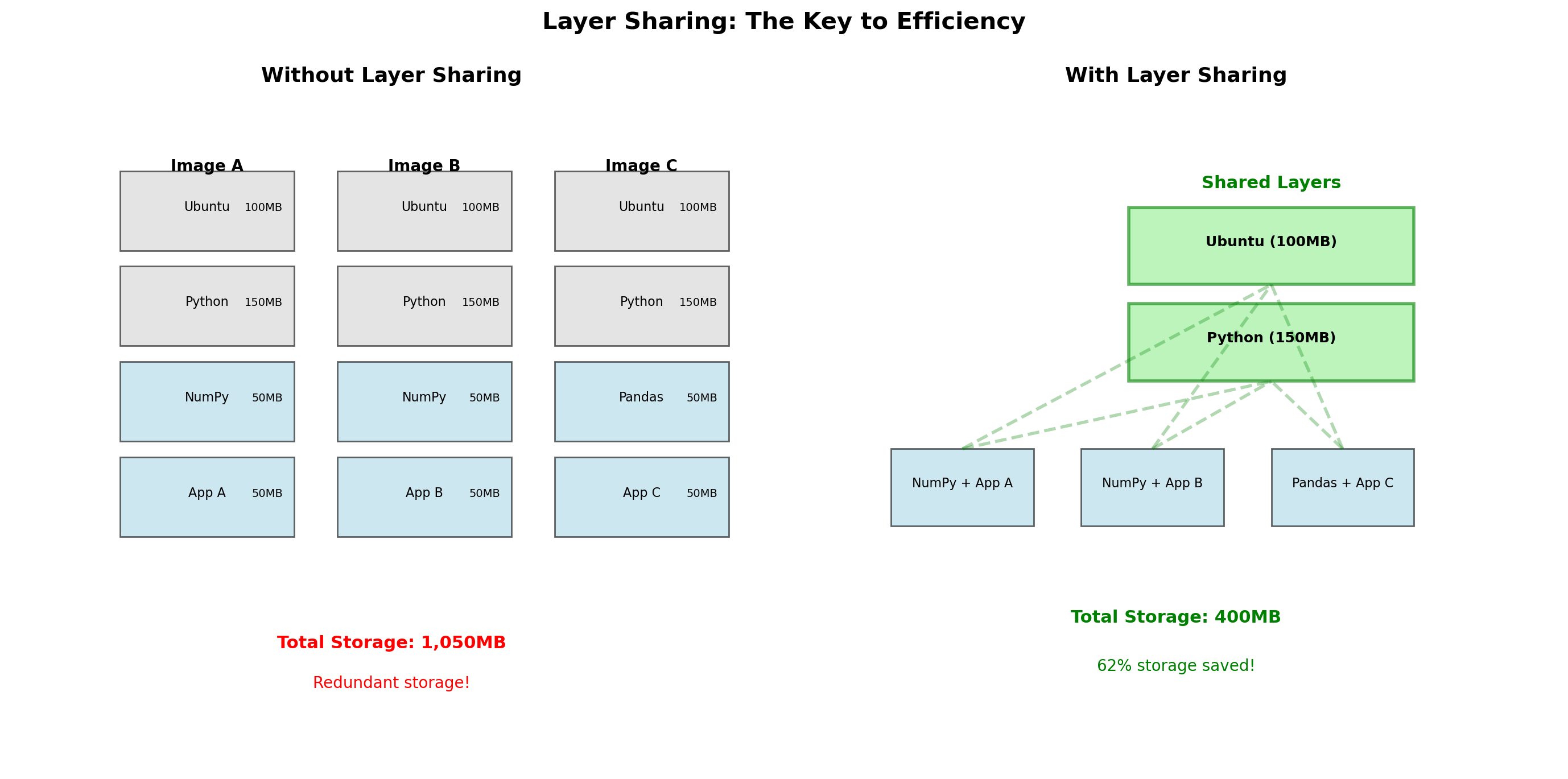

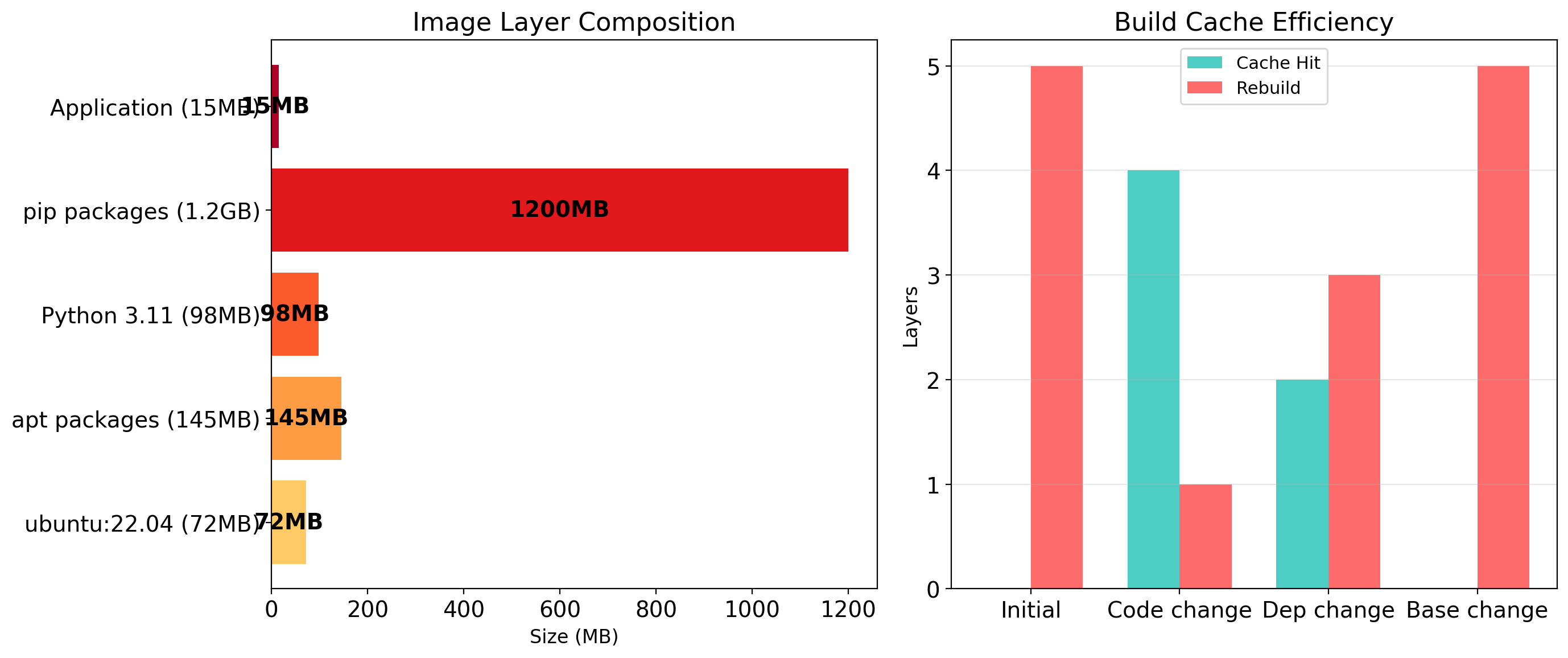

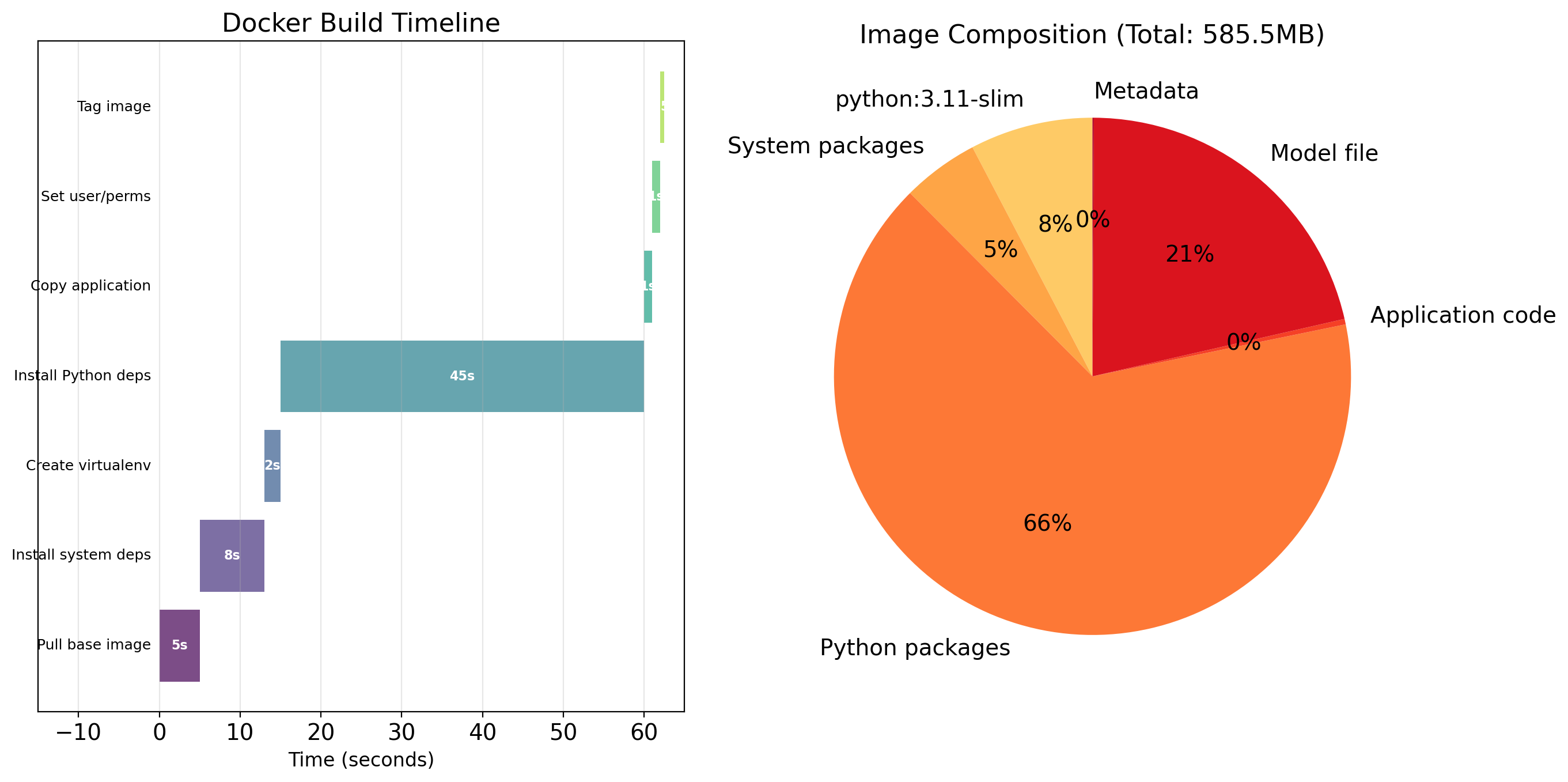

Images Are Built from Layers

An image is not a single blob. It’s a stack of layers.

Each layer represents a change:

- Base layer: Ubuntu filesystem

- Layer 2:

apt install python - Layer 3:

pip install flask - Layer 4: Copy application code

Layers are read-only and content-addressed. If two images share a base layer, they share the actual bytes on disk.

Image A Image B

┌───────────┐ ┌───────────┐

│ my app │ │ other app │

├───────────┤ ├───────────┤

│ flask │ │ django │

├───────────┼───────┼───────────┤

│ python:3.11 │

├─────────────────────────────┤

│ ubuntu │

└─────────────────────────────┘

(shared layers)

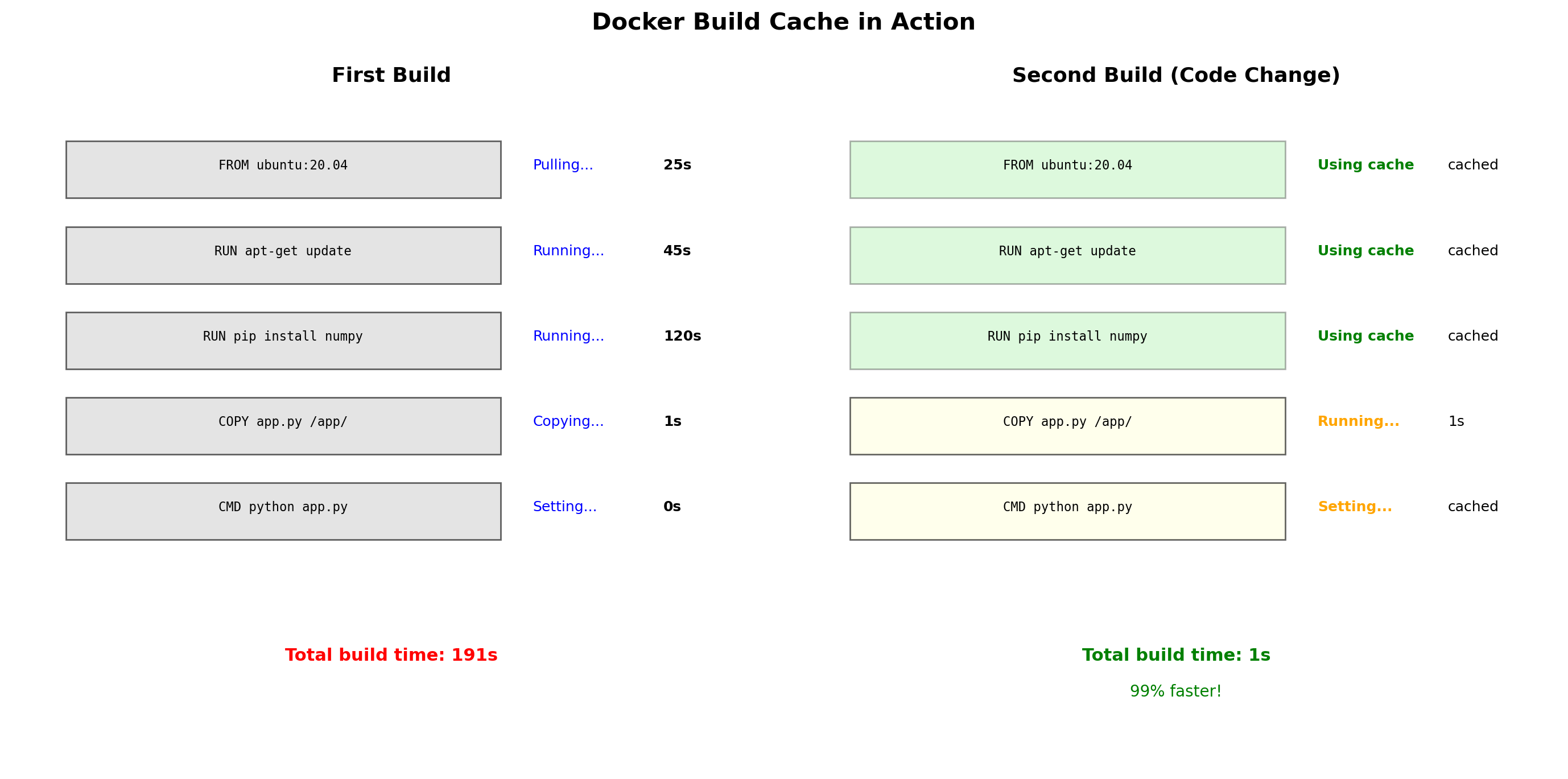

Layer Sharing Saves Space and Time

Storage efficiency

Ten applications using python:3.11 share one copy of that layer. 800 MB base × 10 = 800 MB, not 8 GB.

Distribution efficiency

Pulling a new image version that only changed application code? Only download the changed layer. The base layers are already present.

Build efficiency

Rebuilding after a code change? Docker reuses cached layers that haven’t changed. Only the COPY . /app layer needs to rebuild.

Layer ordering matters

Put things that change frequently (application code) in later layers. Put things that change rarely (OS, dependencies) in earlier layers.

Dockerfiles Define How to Build Images

A Dockerfile is a text file with instructions for building an image.

# Base image

FROM python:3.11-slim

# Set working directory

WORKDIR /app

# Install dependencies (cached if requirements.txt unchanged)

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

# Copy application code (changes frequently)

COPY . .

# Document the port

EXPOSE 8080

# Command to run

CMD ["python", "app.py"]Each instruction creates a layer. Order matters for cache efficiency—put dependencies before application code.

Key instructions:

| Instruction | Purpose |

|---|---|

FROM |

Base image to start from |

WORKDIR |

Set working directory |

COPY |

Add files from build context |

RUN |

Execute command |

ENV |

Set environment variable |

EXPOSE |

Document listening port |

CMD |

Default command to run |

ENTRYPOINT |

Command that always runs |

Building an Image

The build process:

- Docker reads the Dockerfile

- Creates a temporary container from the base image

- Executes each instruction in that container

- Saves the result as a new layer

- Stacks layers into the final image

The build context

The . specifies the build context—the directory whose contents are available to COPY commands. Docker sends this to the daemon before building.

Large build contexts slow down builds. Use .dockerignore to exclude unnecessary files.

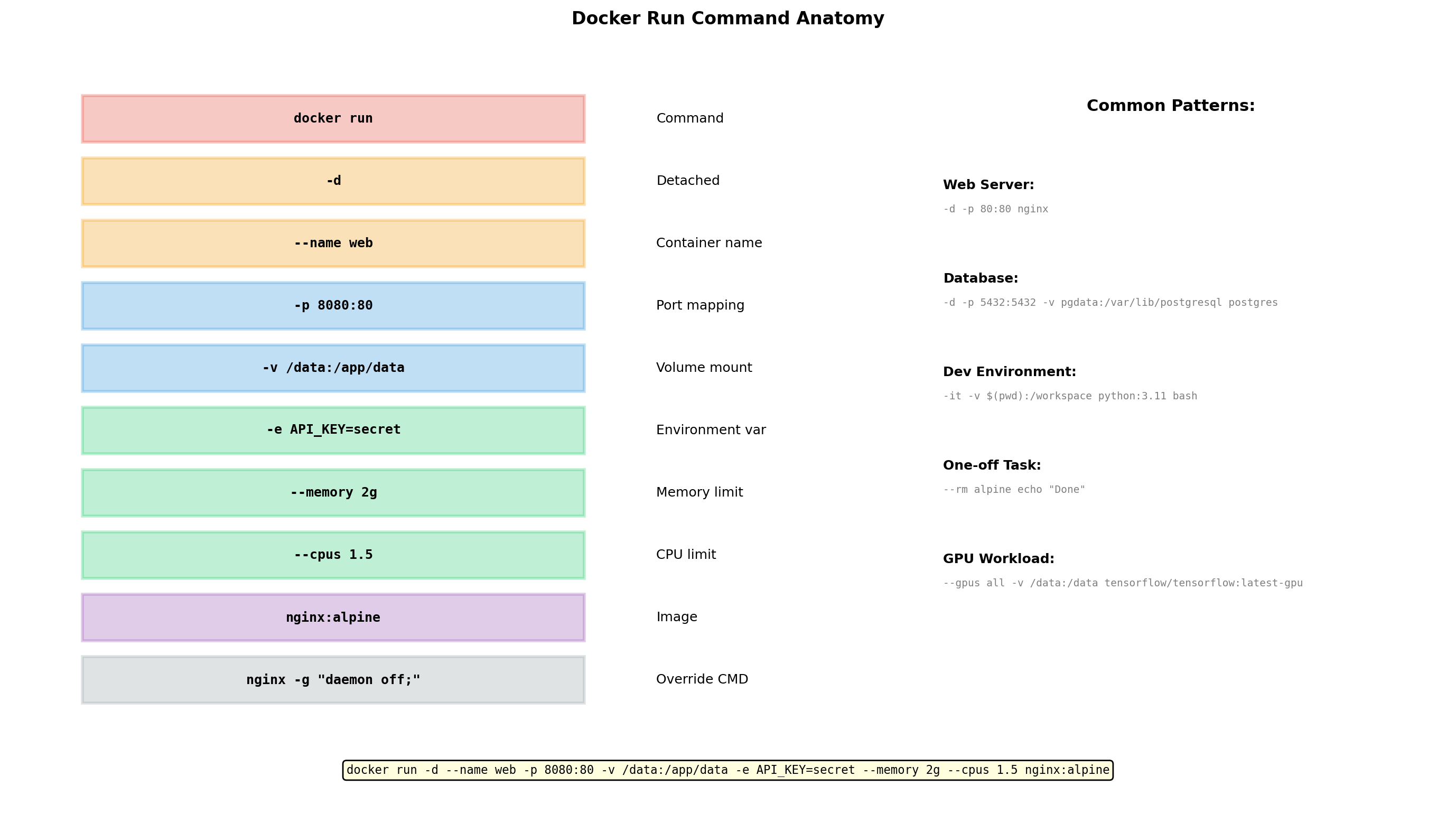

Running a Container

Docker:

- Creates container from image

- Sets up namespaces (PID, mount, network, etc.)

- Creates writable layer on top of image layers

- Configures cgroups if limits specified

- Executes the

CMDorENTRYPOINT

Foreground vs detached

# Foreground - attached to terminal

$ docker run myapp:v1

# Detached - runs in background

$ docker run -d myapp:v1Naming containers

Without --name, Docker assigns a random name.

Port Mapping Connects Containers to the Network

Containers have isolated network namespaces. A container listening on port 8080 is not accessible from the host by default.

Port mapping connects host ports to container ports:

This means: traffic to host port 8080 goes to container port 80.

Host Container

┌──────────┐ -p 8080:80 ┌──────────┐

│ :8080 │ ──────────────> │ :80 │

└──────────┘ └──────────┘Multiple mappings

Container Filesystems Are Ephemeral

Changes to a container’s filesystem are stored in its writable layer. When the container is removed, that layer is deleted.

$ docker run -d --name mydb postgres

$ docker exec mydb psql -c "CREATE TABLE users..."

# Database file created in container's writable layer

$ docker rm -f mydb

# Container removed - data gone

$ docker run -d --name mydb postgres

# Fresh container - no users tableThis is a feature, not a bug. Containers are disposable. Same image always starts from the same state.

But databases, uploaded files, and logs need to persist beyond container lifetime.

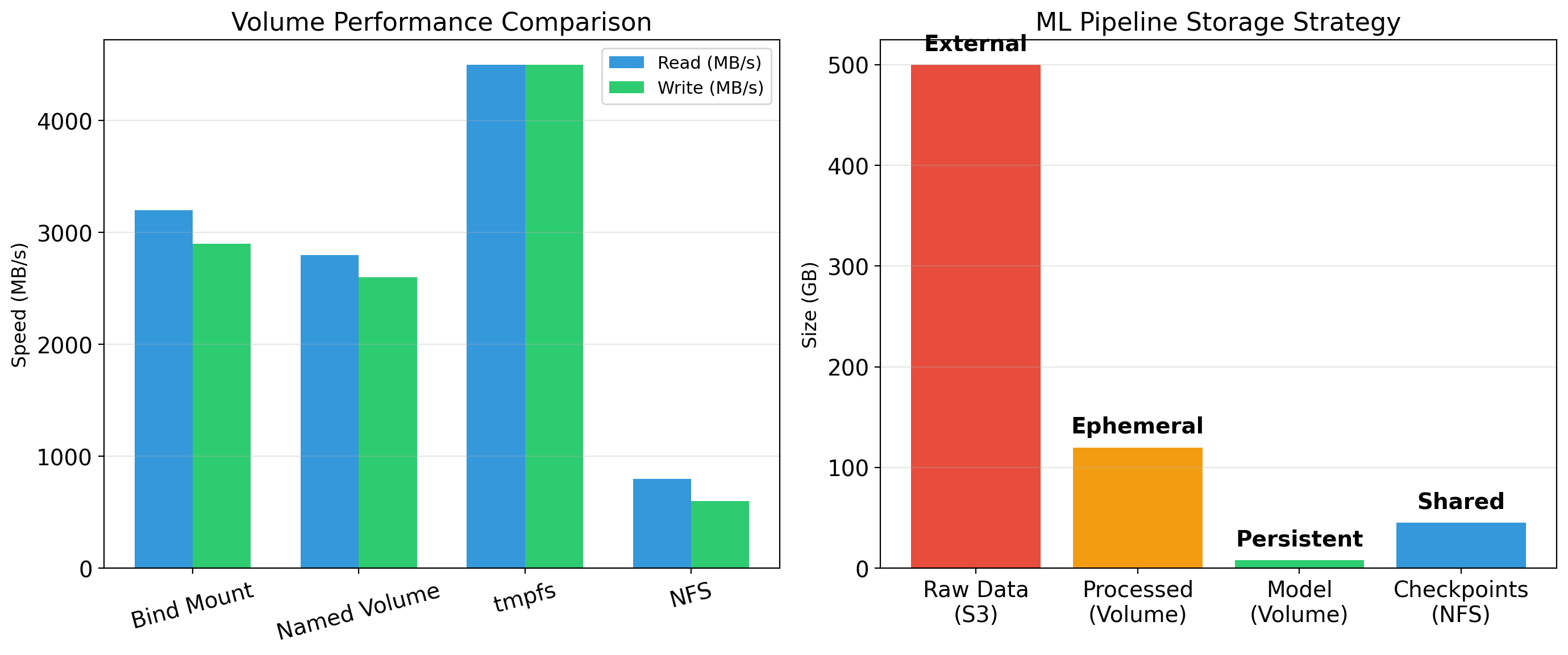

Volumes Persist Data Beyond Container Lifetime

A volume is storage managed by Docker that exists outside the container’s filesystem.

The volume pgdata persists even when the container is removed. A new container can attach to the same volume.

$ docker rm -f mydb

$ docker run -v pgdata:/var/lib/postgresql/data postgres

# Same data, new containerBind mounts map a host directory into the container:

Useful for development—edit code on host, container sees changes.

Environment Variables Configure Containers

Many applications are configured through environment variables. Docker makes this easy:

Inside the container, the application reads these:

Why environment variables?

- Same image, different configuration per environment

- Secrets don’t need to be baked into images

- Twelve-factor app pattern

Multiple variables

Container Networking: Containers Communicate

Containers on the same Docker network can communicate using container names.

# Create a network

$ docker network create mynet

# Run database on that network

$ docker run -d --name db --network mynet postgres

# Run app on same network

$ docker run -d --name api --network mynet \

-e DATABASE_URL=postgres://db:5432/app \

myappThe api container connects to db by name. Docker provides DNS resolution within the network.

No port mapping needed for container-to-container traffic. Port mapping is only for external access.

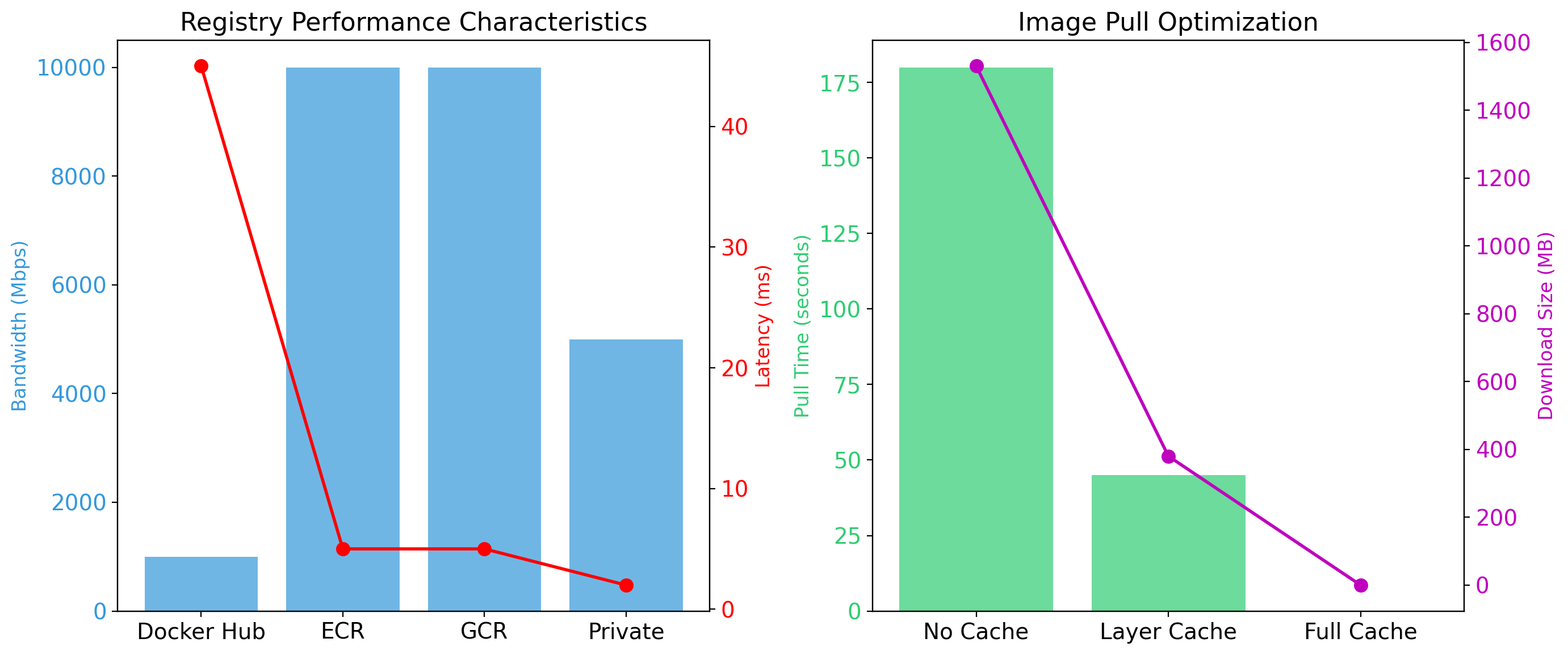

Registries Store and Distribute Images

Images need to move between machines—from build server to production, from developer to teammate.

Docker Hub is the default public registry. Millions of images available.

Private registries for proprietary images:

- Amazon ECR

- Google Container Registry

- Azure Container Registry

- Self-hosted registry

Image naming

registry/repository:tag

gcr.io/my-project/myapp:v1.2.3

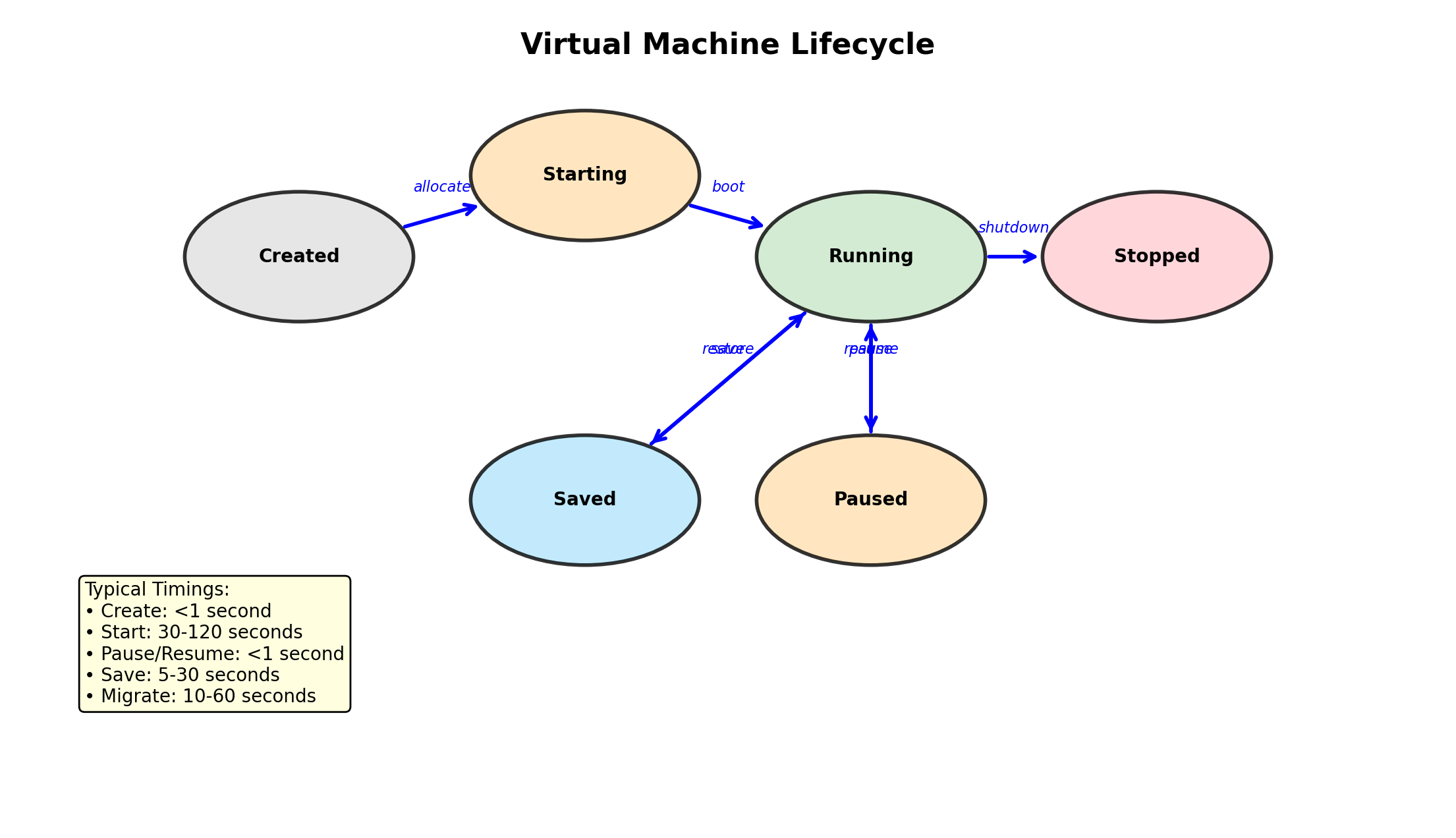

Container Lifecycle

Containers have states:

# Create and start

$ docker run -d --name web nginx

# State: running

# Stop (graceful shutdown)

$ docker stop web

# State: stopped (exited)

# Start again

$ docker start web

# State: running

# Remove

$ docker rm web

# Container deleted

# Force remove running container

$ docker rm -f webListing containers

Common Docker Commands

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

docker build -t name:tag . |

Build image from Dockerfile |

docker run image |

Create and start container |

docker run -d |

Run detached (background) |

docker run -p host:container |

Map ports |

docker run -v vol:/path |

Mount volume |

docker run -e VAR=value |

Set environment variable |

docker ps |

List running containers |

docker logs container |

View container output |

docker exec -it container sh |

Shell into running container |

docker stop container |

Stop container |

docker rm container |

Remove container |

docker images |

List images |

docker pull image |

Download image from registry |

docker push image |

Upload image to registry |

Docker Enables Reproducible Environments

The “works on my machine” problem

- Developer has Python 3.11, server has Python 3.9

- Developer has OpenSSL 3.0, server has 1.1.1

- Developer’s PATH includes local tools

Docker’s solution

The image contains everything the application needs. The same image runs the same way on:

- Developer laptop

- CI/CD server

- Staging environment

- Production

Build the image once. Test it. Deploy the same image to production. No environment drift.

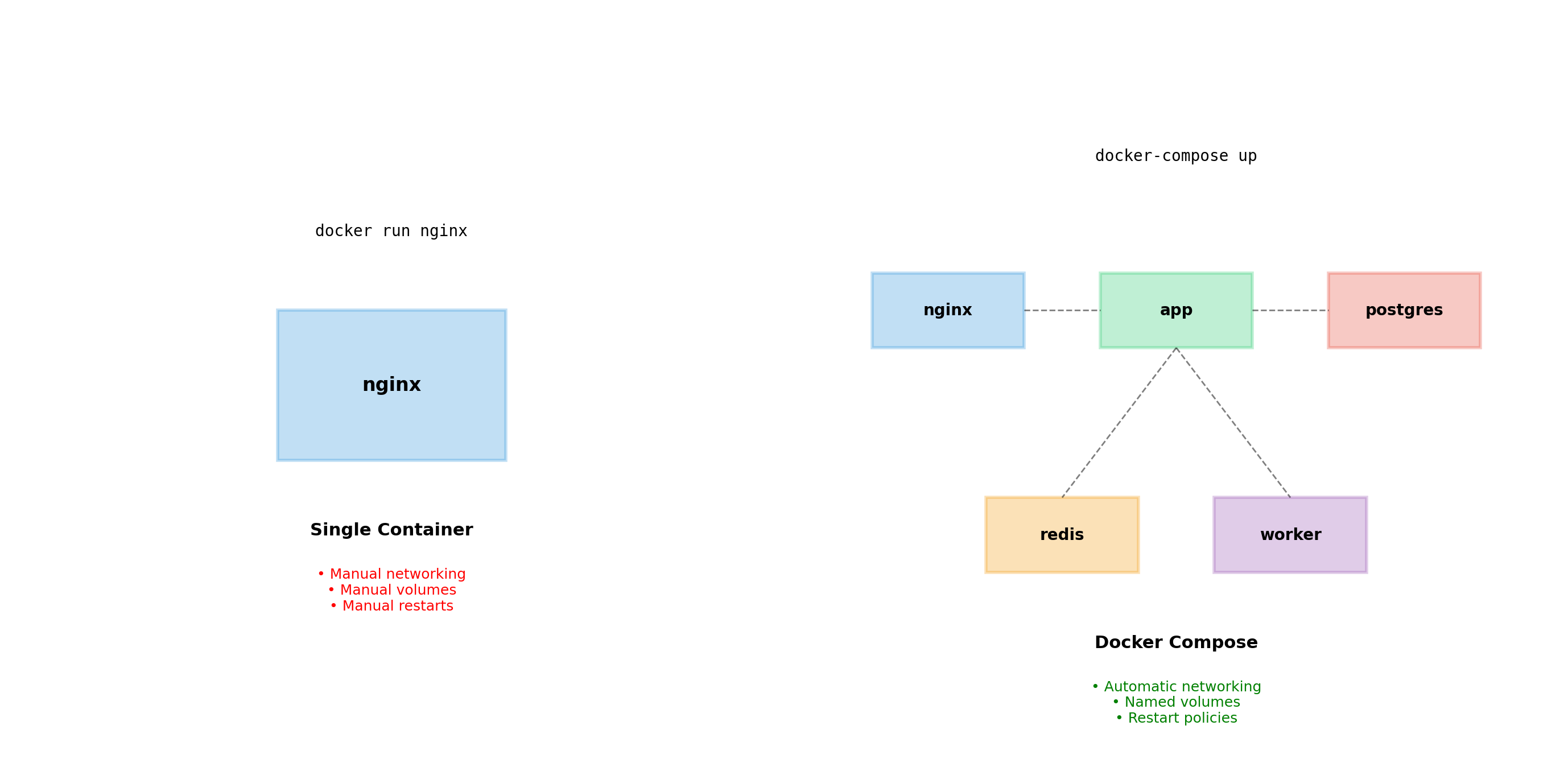

Docker Compose

Real Applications Have Multiple Containers

A web application typically requires several services:

- Web server — handles HTTP, serves static files

- Application server — runs business logic

- Database — stores persistent data

- Cache — speeds up frequent queries

- Background worker — processes async jobs

Each service runs in its own container. They need to communicate, share data, and start in the right order.

With what we’ve covered so far, this means many docker run commands with careful coordination.

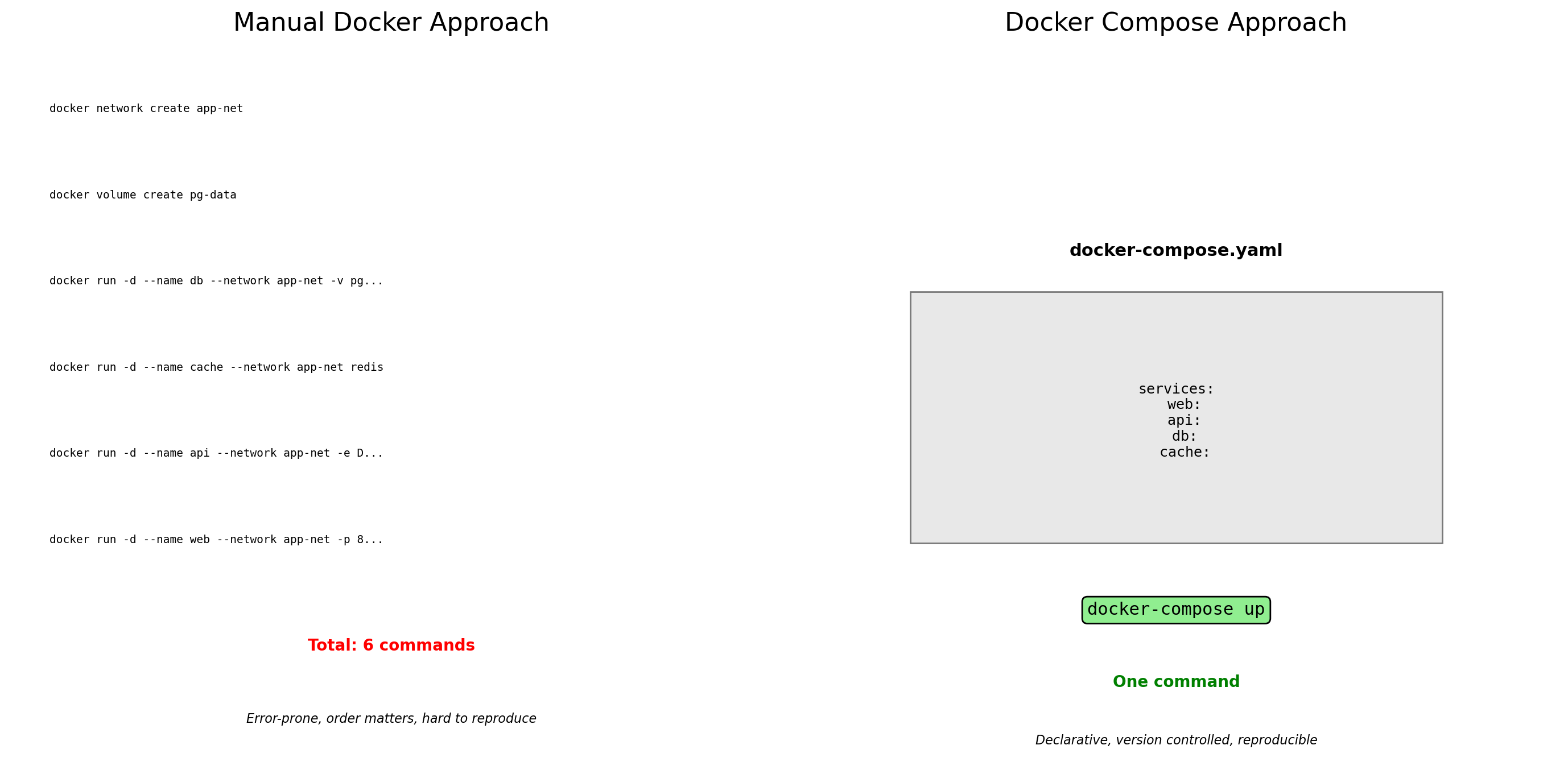

Managing Multiple Containers Manually

Starting the application with individual commands:

# Create network

docker network create myapp

# Start database

docker run -d --name db \

--network myapp \

-v pgdata:/var/lib/postgresql/data \

-e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=secret \

postgres:15

# Start cache

docker run -d --name cache \

--network myapp \

redis:7

# Start API

docker run -d --name api \

--network myapp \

-e DATABASE_URL=postgres://db:5432 \

-e REDIS_URL=redis://cache:6379 \

myapp-api:latest

# Start worker

docker run -d --name worker \

--network myapp \

-e DATABASE_URL=postgres://db:5432 \

-e REDIS_URL=redis://cache:6379 \

myapp-worker:latest

# Start web server

docker run -d --name web \

--network myapp \

-p 80:80 \

nginx:latestProblems with this approach:

Every time you start the application:

- Type or paste 6 long commands

- Get the order right (database before API)

- Remember all environment variables

- Remember all volume mounts

- Hope you didn’t make a typo

Every time you share with a teammate:

- Copy the commands somewhere

- Explain what each flag means

- Hope they run them correctly

Every time you update:

- Stop containers manually

- Remove them

- Run the commands again with changes

Error-prone, tedious, not reproducible.

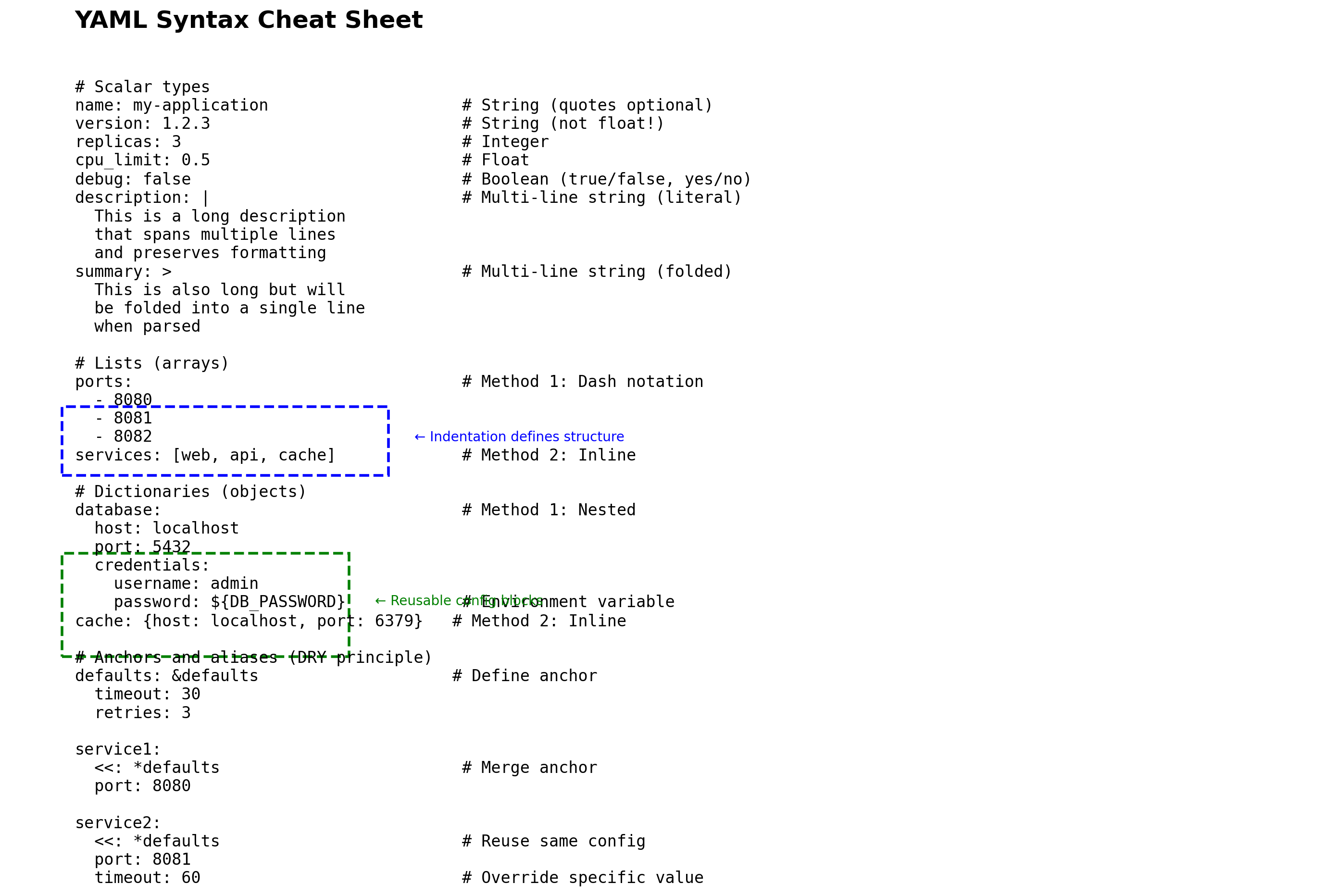

Docker Compose: Infrastructure as Code

Docker Compose replaces manual commands with a declarative YAML file.

docker-compose.yaml:

services:

db:

image: postgres:15

volumes:

- pgdata:/var/lib/postgresql/data

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: secret

cache:

image: redis:7

api:

build: ./api

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgres://db:5432

REDIS_URL: redis://cache:6379

depends_on:

- db

- cache

worker:

build: ./worker

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgres://db:5432

REDIS_URL: redis://cache:6379

depends_on:

- db

- cache

web:

image: nginx:latest

ports:

- "80:80"

depends_on:

- api

volumes:

pgdata:Starting the application:

One command. The file defines everything.

Benefits:

- Version controlled with your code

- Self-documenting

- Reproducible across machines

- Shareable with teammates

- No commands to memorize

The YAML file becomes the source of truth for your application’s infrastructure.

Compose File Structure

A docker-compose.yaml has several top-level sections:

services

The containers that make up your application. Each service becomes a container (or multiple containers if scaled).

volumes

Named volumes that persist data. Referenced by services.

networks (optional)

Custom networks for container communication. If not specified, Compose creates a default network.

The default network

Compose automatically creates a network for your application. All services join this network and can reach each other by service name.

Service named db is reachable at hostname db. No manual network creation needed.

Service Configuration Options

Image or build

# Use existing image

api:

image: nginx:1.24

# Build from Dockerfile

api:

build: ./api

# or with options:

build:

context: ./api

dockerfile: Dockerfile.prodPorts

Environment variables

depends_on Controls Start Order, Not Readiness

A common misconception: depends_on waits for the dependency to be “ready.”

What actually happens:

Compose starts db first, then starts api immediately after.

It does not wait for:

- PostgreSQL to finish initializing

- The database to accept connections

- Any health check to pass

The problem:

Database containers often take several seconds to initialize. Your API container starts, tries to connect, and fails because the database isn’t ready yet.

Handling Startup Dependencies

Option 1: Application-level retries

The application handles connection failures gracefully:

import time

import psycopg2

def connect_with_retry(url, max_attempts=30):

for attempt in range(max_attempts):

try:

return psycopg2.connect(url)

except psycopg2.OperationalError:

print(f"DB not ready, retry {attempt+1}")

time.sleep(1)

raise Exception("Could not connect to database")This is the most robust approach. Applications should handle transient failures anyway.

Option 2: Health checks with condition

Compose can wait for health checks:

services:

db:

image: postgres:15

healthcheck:

test: ["CMD", "pg_isready"]

interval: 5s

timeout: 5s

retries: 5

api:

depends_on:

db:

condition: service_healthyThis waits for db to pass its health check before starting api.

More complex setup, but useful when you can’t modify the application.

Compose Creates a Default Network

When you run docker compose up, Compose automatically:

- Creates a network named

{project}_default - Connects all services to this network

- Sets up DNS so services can reach each other by name

services:

api:

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgres://db:5432/app

# ^^

# Service name becomes hostnameThe api container can connect to db:5432. Docker’s internal DNS resolves db to the database container’s IP address.

No need to know IP addresses. No need to create networks manually. Service names are stable identifiers.

Compose Commands

Starting services

# Start all services

docker compose up

# Start in background (detached)

docker compose up -d

# Start specific service

docker compose up api

# Rebuild images before starting

docker compose up --buildStopping services

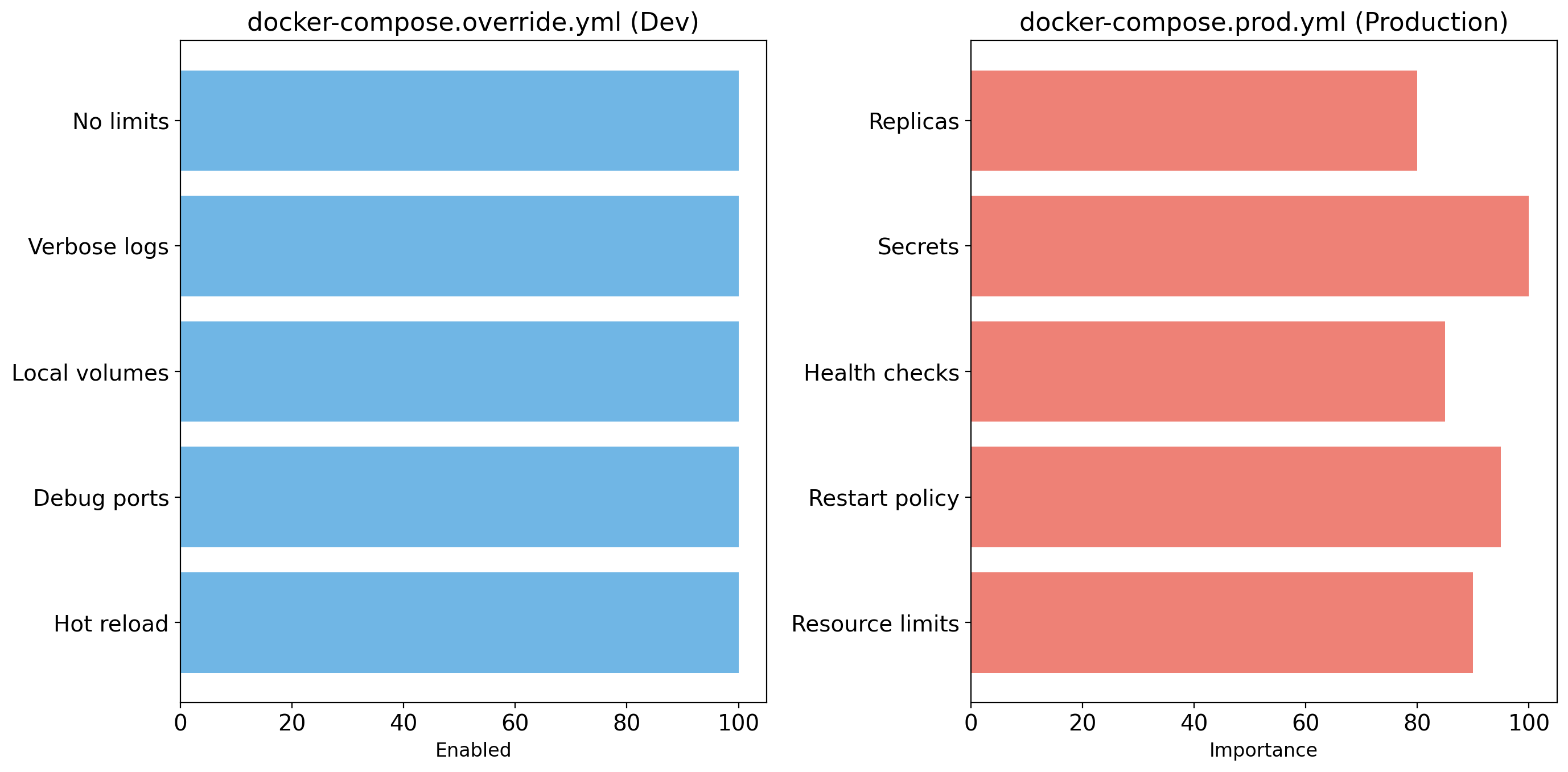

Development Workflow with Compose

Compose is particularly valuable for local development.

Mount source code for live reload:

services:

api:

build: ./api

volumes:

- ./api:/app # Mount local code into container

environment:

FLASK_DEBUG: "1" # Enable auto-reloadEdit code on your machine. The container sees changes immediately. Flask (or your framework’s dev server) reloads automatically.

Override files for dev vs prod:

Compose File for a Typical Web Application

services:

web:

image: nginx:1.24

ports:

- "80:80"

volumes:

- ./nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro

depends_on:

- api

api:

build: ./api

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgres://postgres:secret@db:5432/app

REDIS_URL: redis://cache:6379

depends_on:

- db

- cache

worker:

build: ./worker

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgres://postgres:secret@db:5432/app

REDIS_URL: redis://cache:6379

depends_on:

- db

- cache

db:

image: postgres:15

volumes:

- pgdata:/var/lib/postgresql/data

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: secret

POSTGRES_DB: app

cache:

image: redis:7

volumes:

pgdata:What Compose Does Well

Local development environments

Define the full stack once. Every developer runs the same environment. No “works on my machine” for local dependencies.

CI/CD testing

Spin up the application with its dependencies for integration tests. Tear down cleanly after tests complete.

Small-scale deployments

Single-server production is viable for many applications. Compose provides a clean way to manage it.

Documentation

The compose file documents your architecture. What services exist, how they connect, what they need.

Simple orchestration

Startup order, restart policies, health checks, logging—all declarative. No shell scripts to maintain.

Reproducibility

Check the compose file into version control. Anyone can run the same stack with docker compose up.

Rapid iteration

Bind mounts for live code reloading. Quickly test changes without rebuilding images.

What Compose Does Not Do

Multi-host deployment

Compose runs containers on a single machine. It cannot spread containers across multiple servers.

High availability

The host machine is a single point of failure. Machine goes down, application goes down.

Auto-scaling

Cannot automatically add containers based on load. Scaling requires manual intervention.

Rolling updates

No built-in zero-downtime deployments. docker compose up restarts containers, causing brief downtime.

Service discovery across hosts

DNS works within the Compose network on one host. No mechanism for cross-host service discovery.

Production-grade orchestration

For these capabilities, you need Kubernetes or a similar orchestration platform.

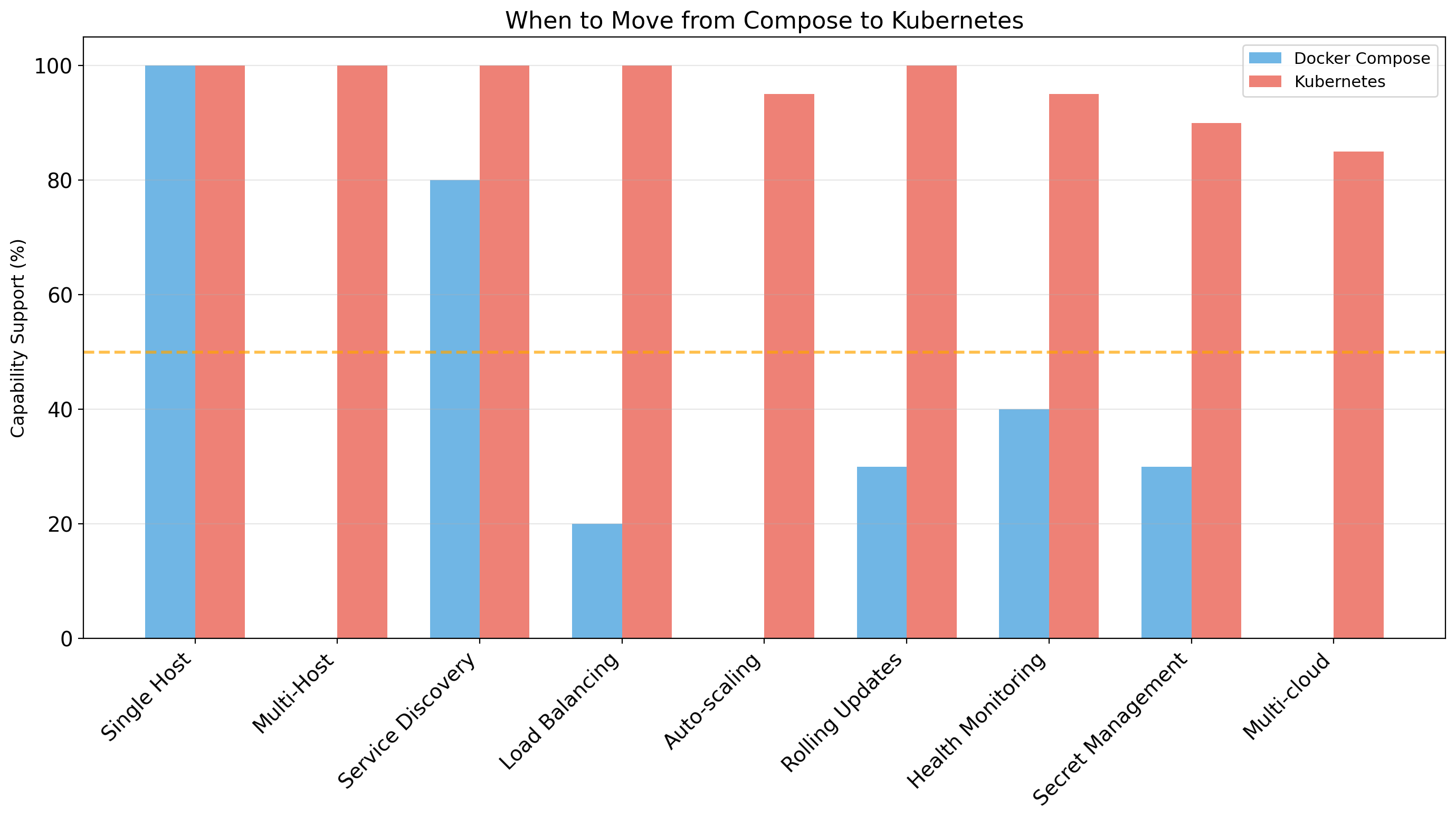

Compose vs Kubernetes: Different Tools, Different Scale

Compose is often sufficient. Don’t add Kubernetes complexity until you need its capabilities.

Common Compose Patterns

Shared environment variables

x-common-env: &common-env

DATABASE_URL: postgres://db:5432/app

REDIS_URL: redis://cache:6379

services:

api:

environment:

<<: *common-env

worker:

environment:

<<: *common-envMultiple instances of a service

Runs 3 worker containers. Useful for parallel processing.

Profiles for optional services

Extending services

Compose Command Reference

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

docker compose up |

Create and start containers |

docker compose up -d |

Start in background |

docker compose up --build |

Rebuild images first |

docker compose down |

Stop and remove containers |

docker compose down -v |

Also remove volumes |

docker compose ps |

List containers |

docker compose logs |

View output |

docker compose logs -f service |

Follow specific service |

docker compose exec service cmd |

Run command in container |

docker compose run service cmd |

Run one-off container |

docker compose build |

Build images |

docker compose pull |

Pull latest images |

docker compose restart |

Restart services |

Container Orchestration

Docker Compose Manages Containers on One Host

Compose solves multi-container coordination on a single machine:

- Define services in YAML

- Bring up entire application with one command

- Containers communicate by service name

- Shared volumes for data persistence

This works well for:

- Local development

- CI/CD testing

- Small-scale deployments

But the application runs on one machine. That machine is a single point of failure.

Single Host Limitations

Capacity ceiling

One machine has finite CPU, memory, disk. When the application needs more resources than one machine provides, Compose cannot help.

No fault tolerance

Machine fails (hardware, power, network) and the entire application goes down. No automatic failover.

Scaling constraints

Can run multiple containers of the same service, but all compete for the same machine’s resources. Cannot scale horizontally across machines.

Maintenance challenges

OS updates require application downtime. Hardware replacement means migrating everything manually.

Resource inefficiency

Some services need more resources at different times. Cannot dynamically redistribute across machines based on load.

Running production workloads on a single host means accepting these limitations—or finding a solution that spans multiple machines.

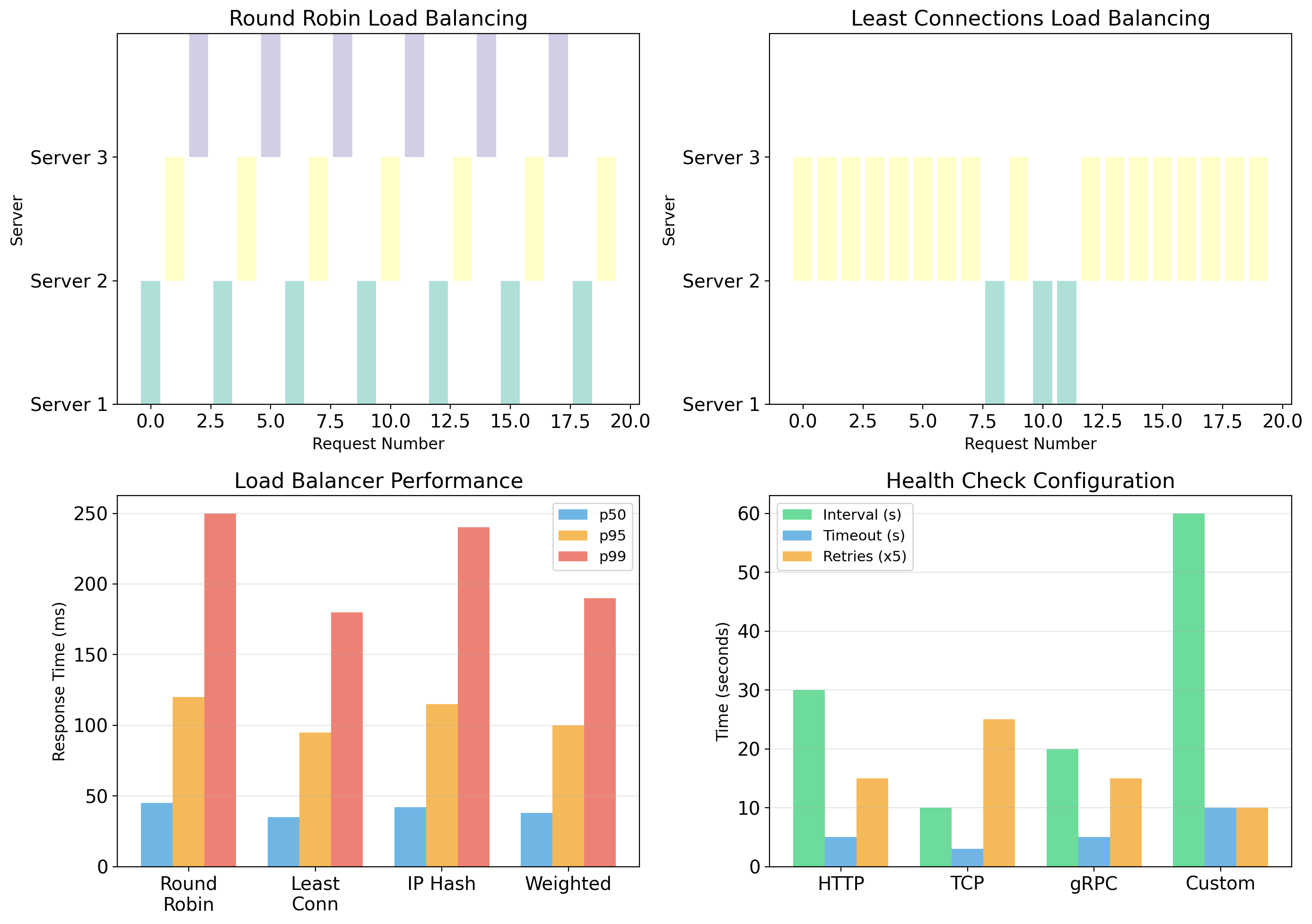

Multi-Host Deployment Requires Coordination

Running containers across multiple machines introduces new problems:

Scheduling

Which container runs on which machine? Need to consider available resources, existing workloads, constraints.

Networking

Containers on different hosts need to communicate. Container on Host A needs to reach container on Host B.

Service discovery

IP addresses change when containers restart or move. How do services find each other?

Failure recovery

Container crashes or host fails. Who notices? Who restarts the container? On which host?

Rolling updates

Deploying new version without downtime. Gradually replace old containers with new ones.

Container Orchestration Systems

Orchestration systems manage containers across clusters of machines.

They handle:

- Scheduling: Deciding where containers run

- Scaling: Running more or fewer instances based on demand

- Networking: Connecting containers across hosts

- Self-healing: Detecting and recovering from failures

- Rolling updates: Deploying new versions without downtime

- Configuration: Injecting settings and secrets

Major orchestration systems:

- Kubernetes — The dominant platform, originally from Google

- Docker Swarm — Docker’s built-in orchestration (simpler, less adopted)

- Amazon ECS — AWS-specific container service

- Nomad — HashiCorp’s alternative

Kubernetes Dominates Container Orchestration

Kubernetes (K8s) emerged from Google’s internal container system (Borg). Open-sourced in 2014, now maintained by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation.

Why Kubernetes won:

- Open source with broad industry support

- Runs on any infrastructure (cloud, on-premise, hybrid)

- Extensive ecosystem of tools and extensions

- All major cloud providers offer managed Kubernetes

Market reality:

Most organizations running containers at scale use Kubernetes. Job postings for “DevOps” or “Platform Engineer” typically require Kubernetes experience.

Understanding Kubernetes concepts—even without operating clusters—is valuable background for working in modern infrastructure.

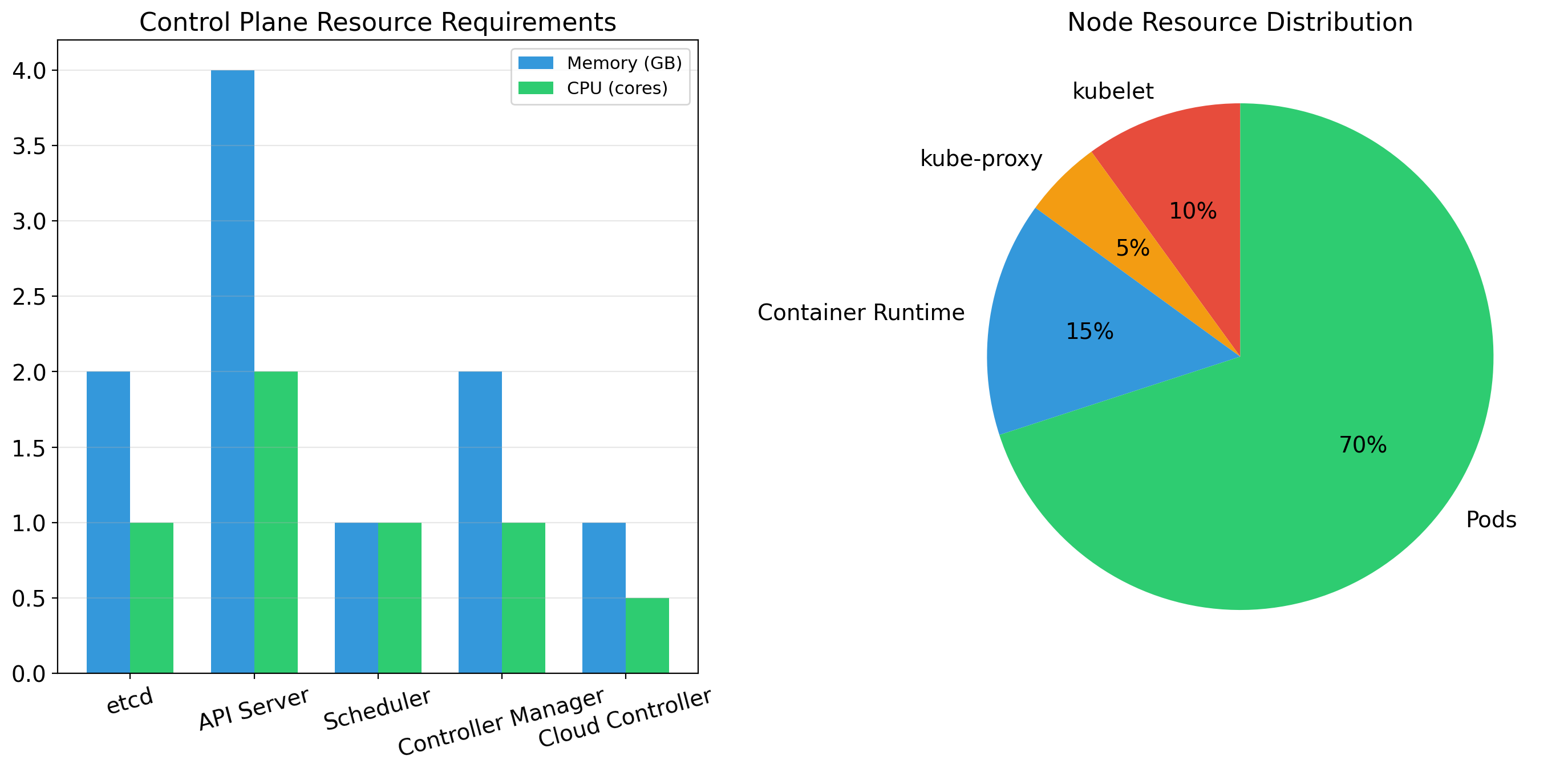

Kubernetes Cluster Architecture

A Kubernetes cluster has two types of machines:

Control Plane (master nodes)

The “brain” of the cluster. Runs:

- API Server: All operations go through REST API

- Scheduler: Decides which node runs each workload

- Controller Manager: Maintains desired state

- etcd: Distributed database storing cluster state

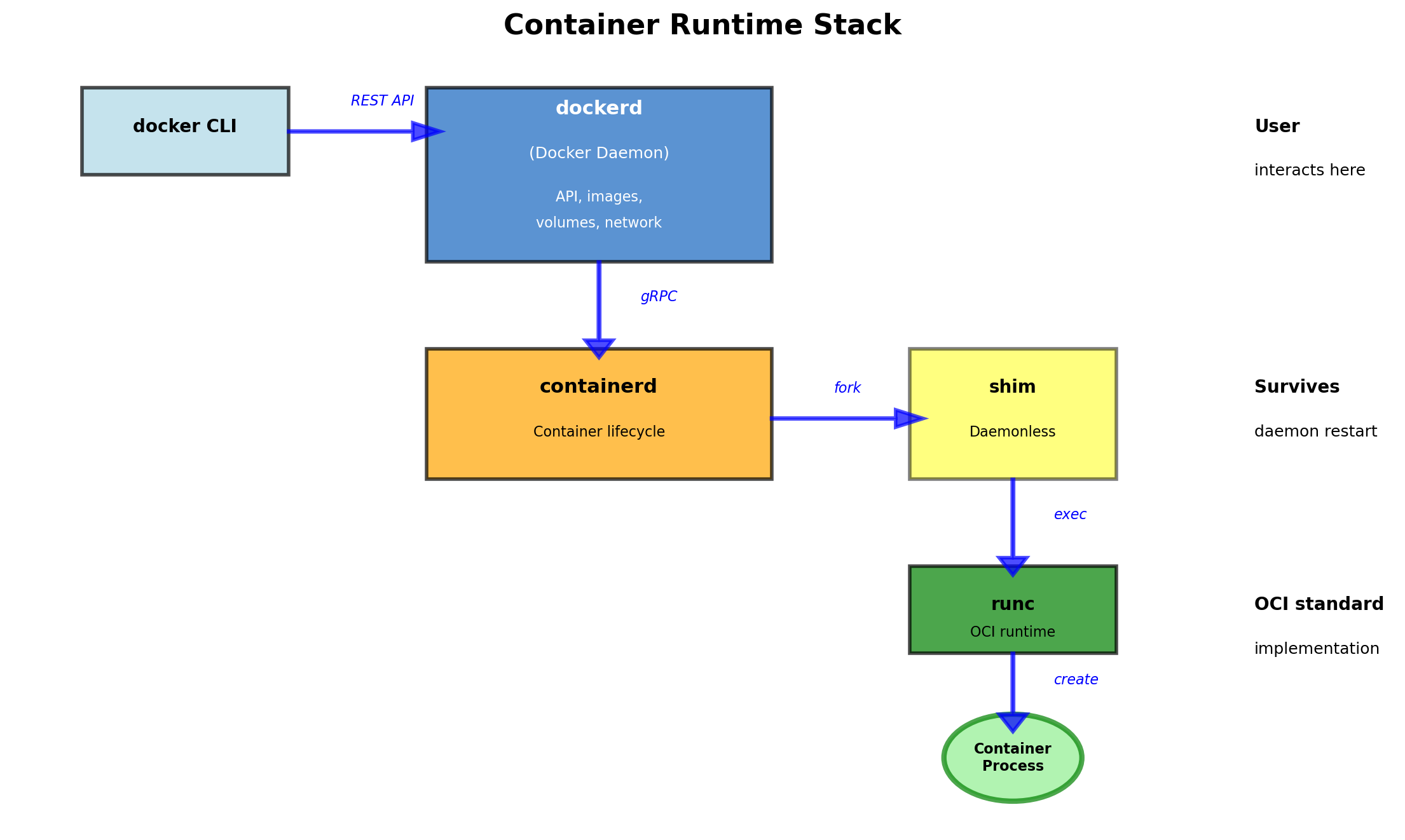

Worker Nodes

The machines that run your containers:

- Kubelet: Agent that manages containers on the node

- Container Runtime: Actually runs containers (containerd, CRI-O)

- Kube-proxy: Handles networking for services

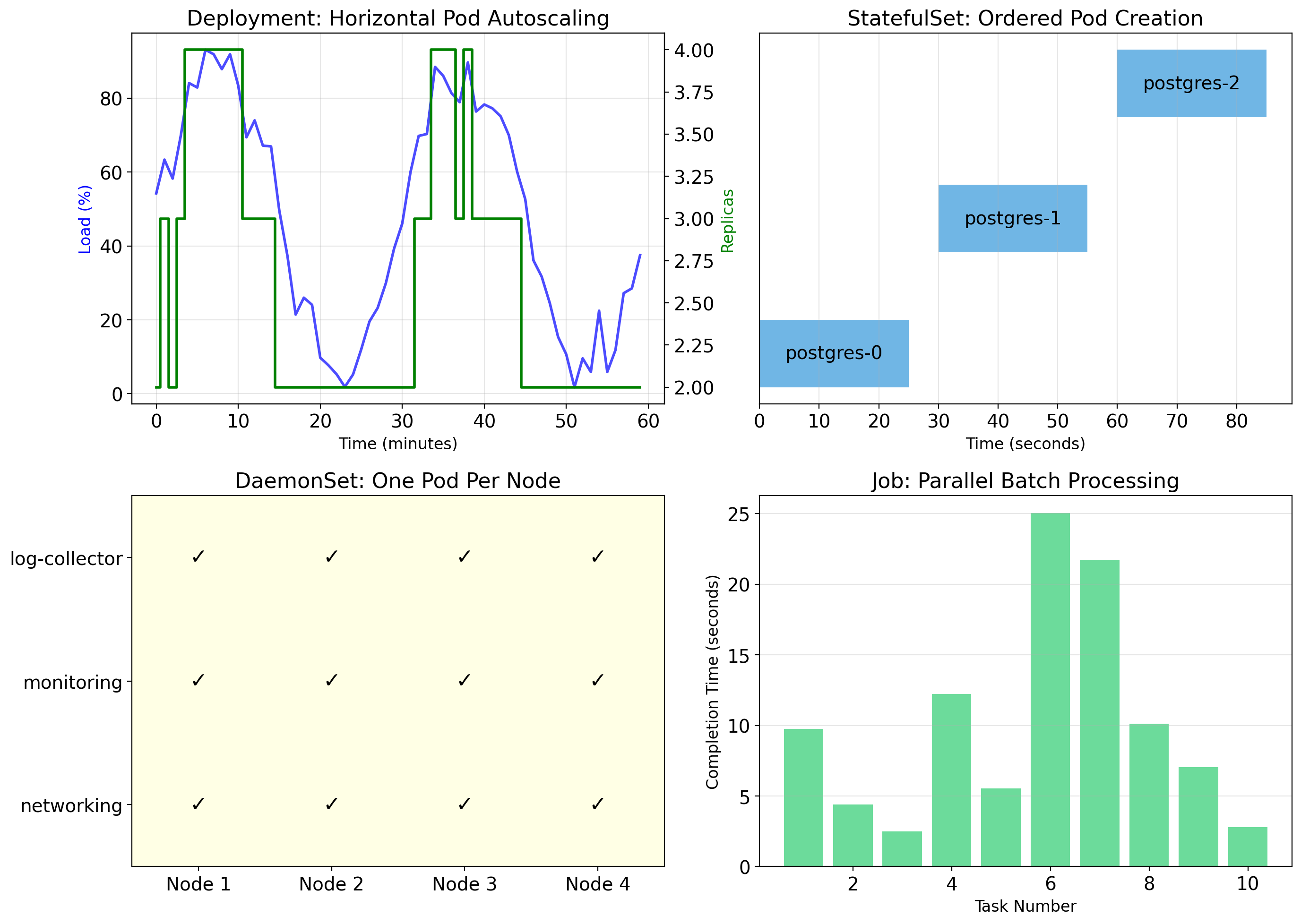

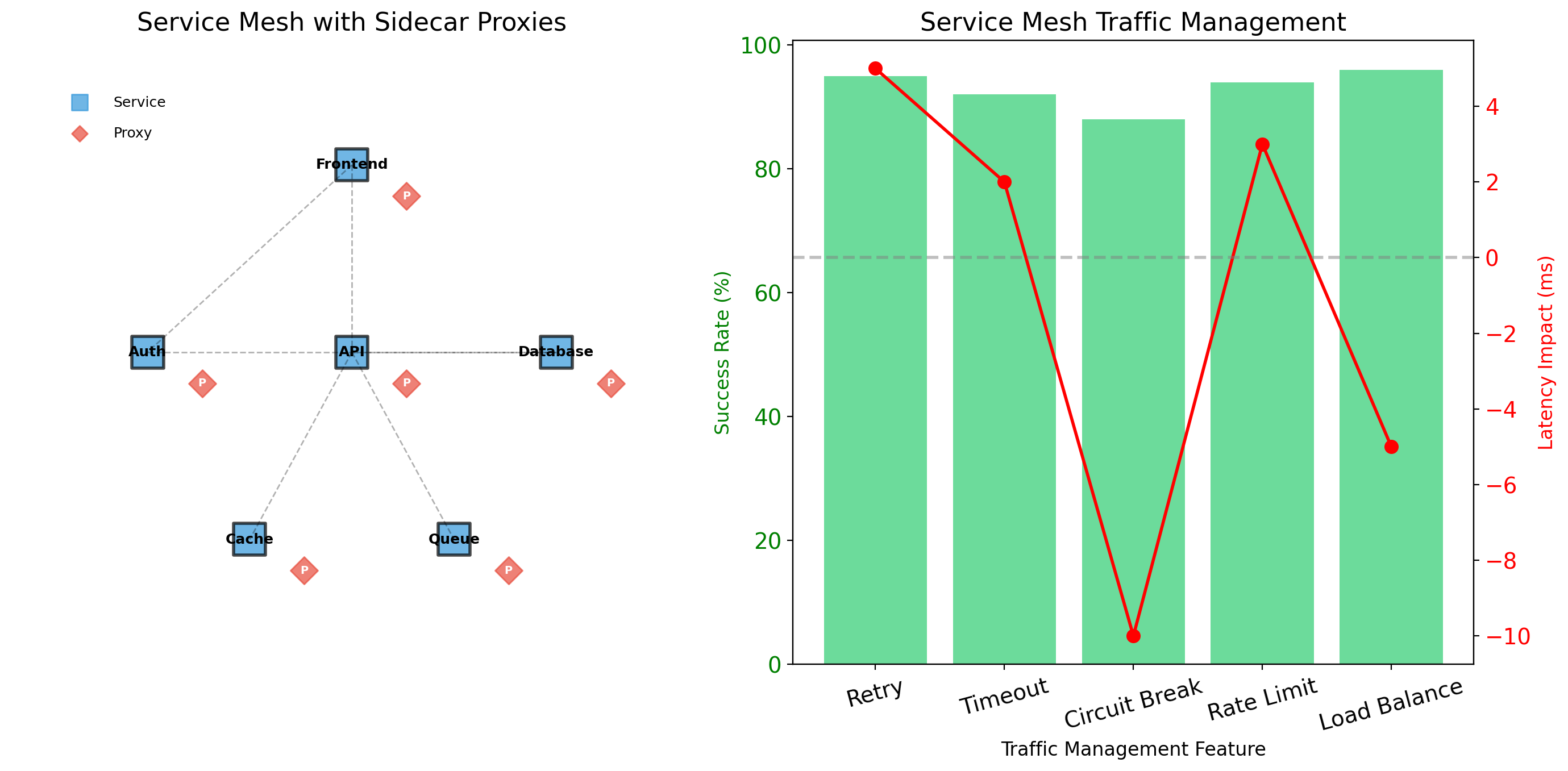

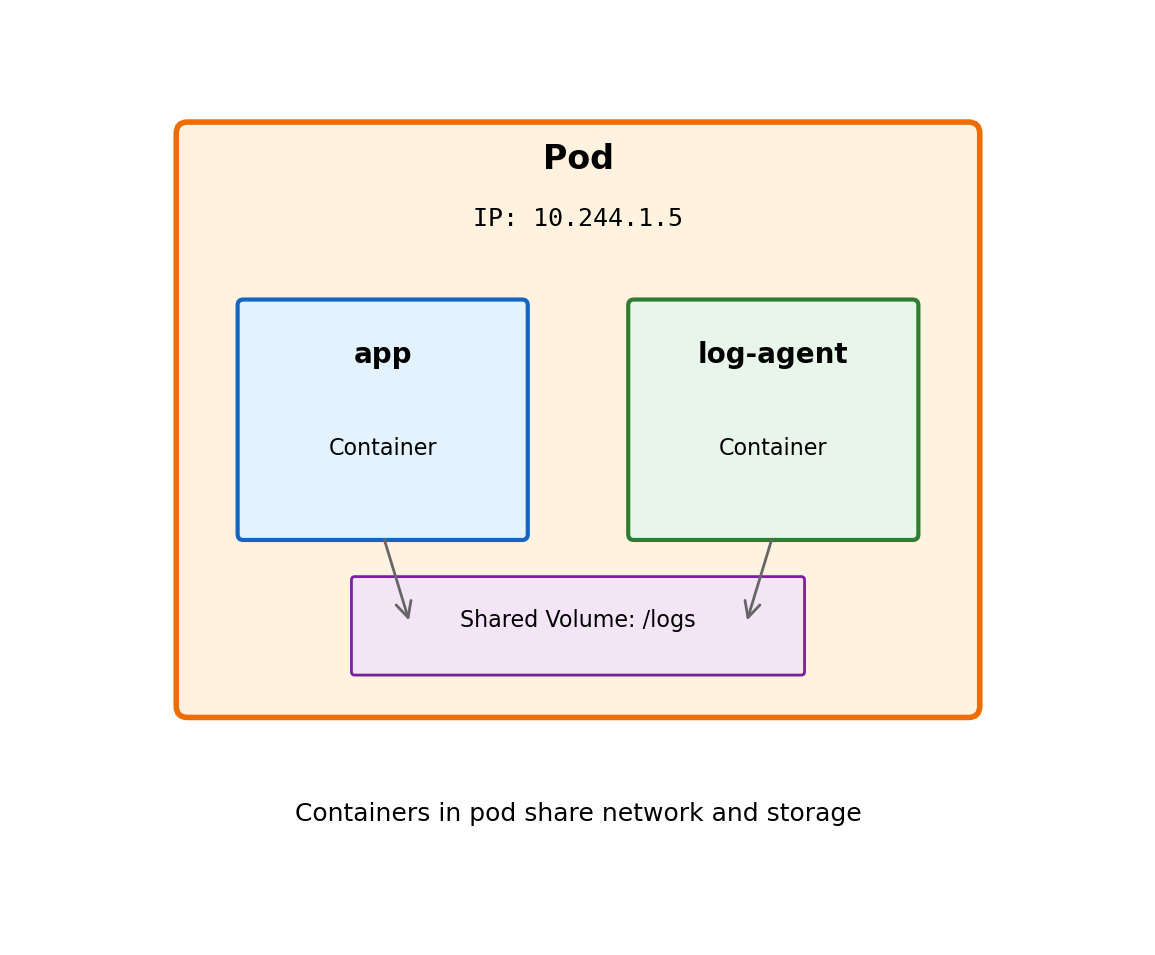

Pods: The Smallest Deployable Unit

Kubernetes does not manage containers directly. It manages Pods.

A Pod is:

- One or more containers that share resources

- The atomic unit of scheduling

- What Kubernetes creates, destroys, and moves

Containers in a Pod share:

- Network namespace (same IP address, localhost communication)

- Storage volumes

- Lifecycle (scheduled together, start/stop together)

Why not just containers?

Sometimes tightly-coupled containers need to be co-located. A logging sidecar that reads another container’s files. A proxy that handles network traffic for the main application.

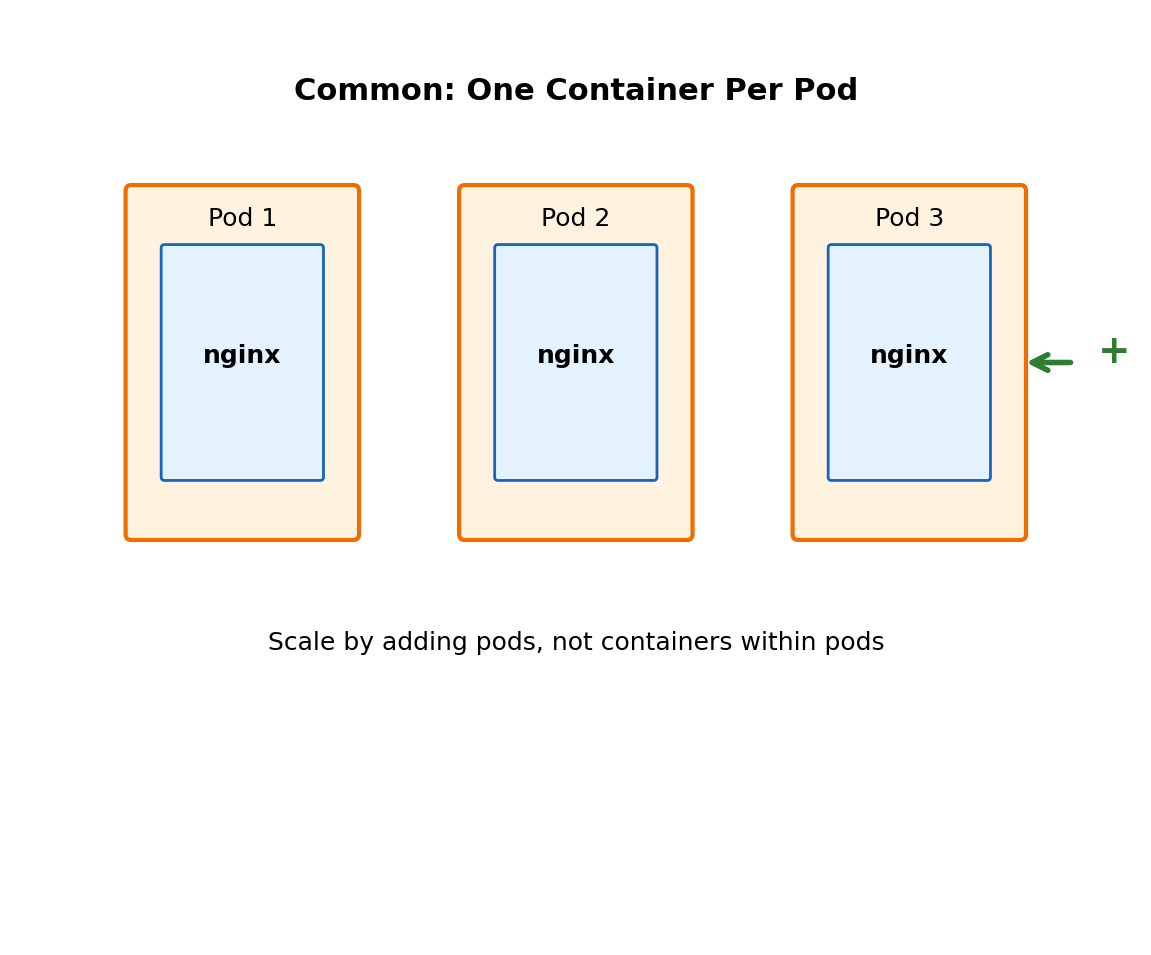

Most Pods Have One Container

Multi-container pods exist for specific patterns:

- Sidecar: Helper container (logging, monitoring, proxy)

- Ambassador: Proxy that simplifies network communication

- Adapter: Transform output format of main container

But the common case is one container per pod.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: web-server

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.24

ports:

- containerPort: 80The pod is the management unit. Kubernetes schedules the pod, not the container. When you scale up, you add pods—each containing its container.

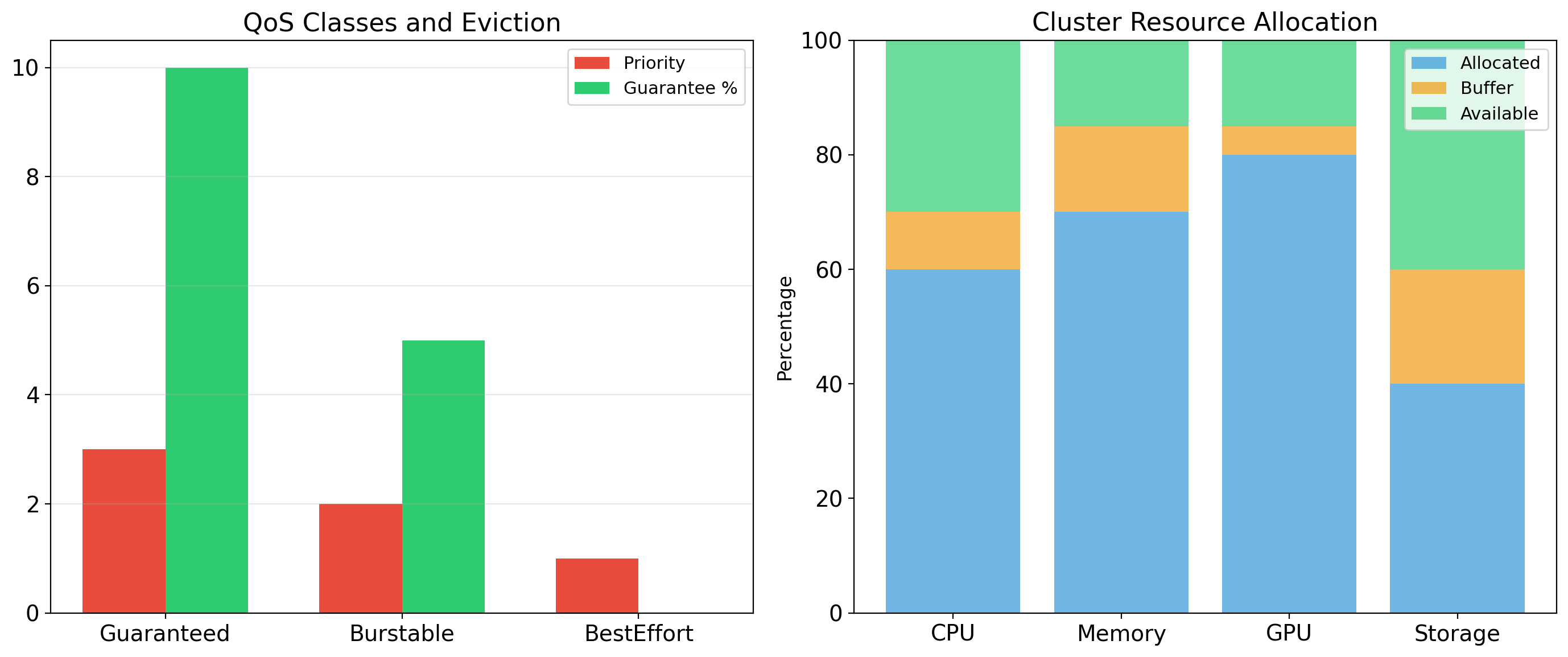

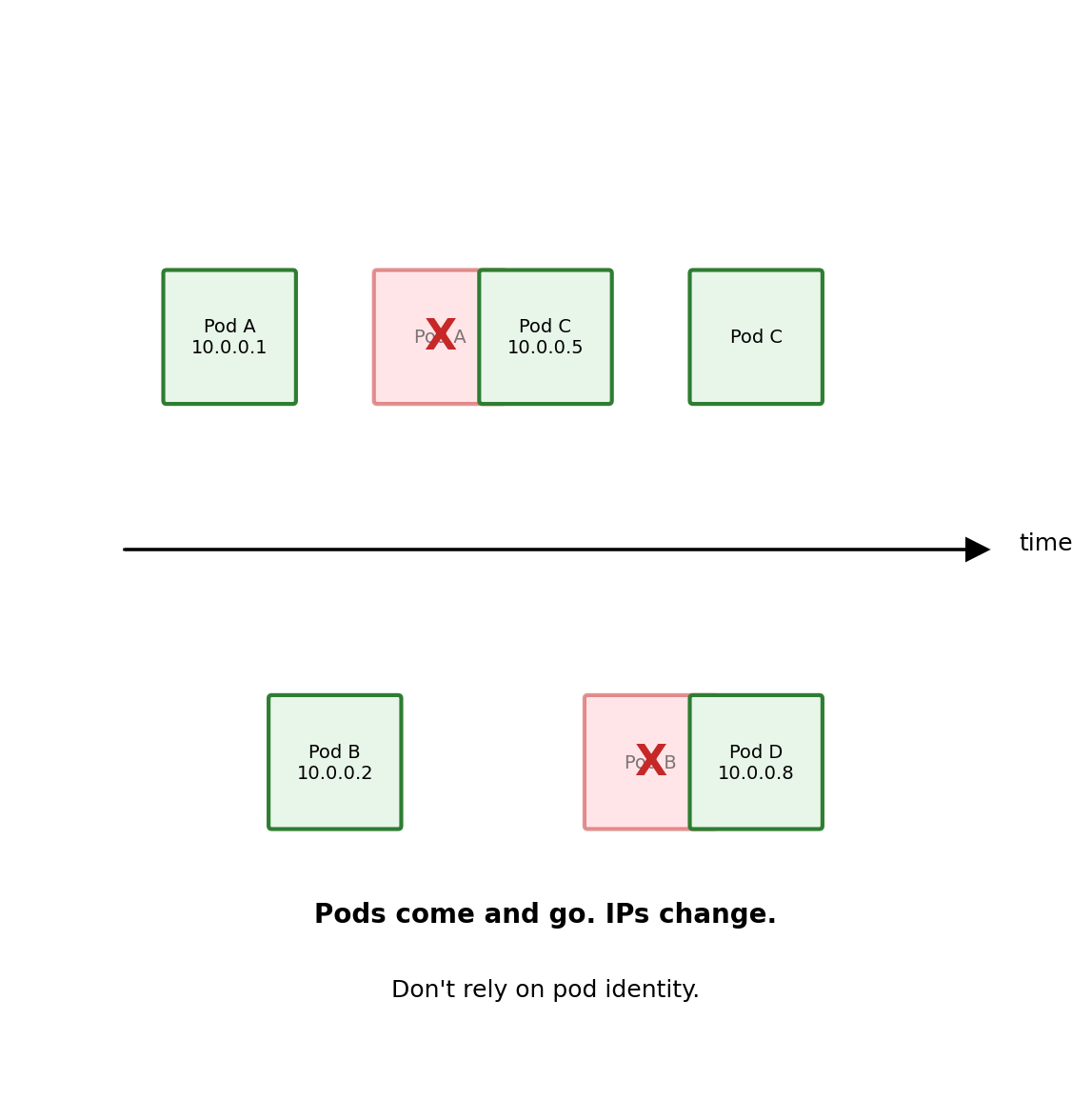

Pods Are Ephemeral

Pods are not permanent. They can be:

- Killed by the scheduler to free resources

- Evicted when a node runs out of memory

- Lost when a node fails

- Replaced during rolling updates

Each new pod gets a new IP address. You cannot rely on a pod’s identity persisting.

This is different from traditional servers where applications run on stable machines with fixed IPs.

Implication:

Don’t connect to pods directly by IP. Don’t store important data only in a pod’s filesystem. Treat pods as disposable.

Kubernetes provides abstractions (Services, Deployments) that handle this ephemerality.

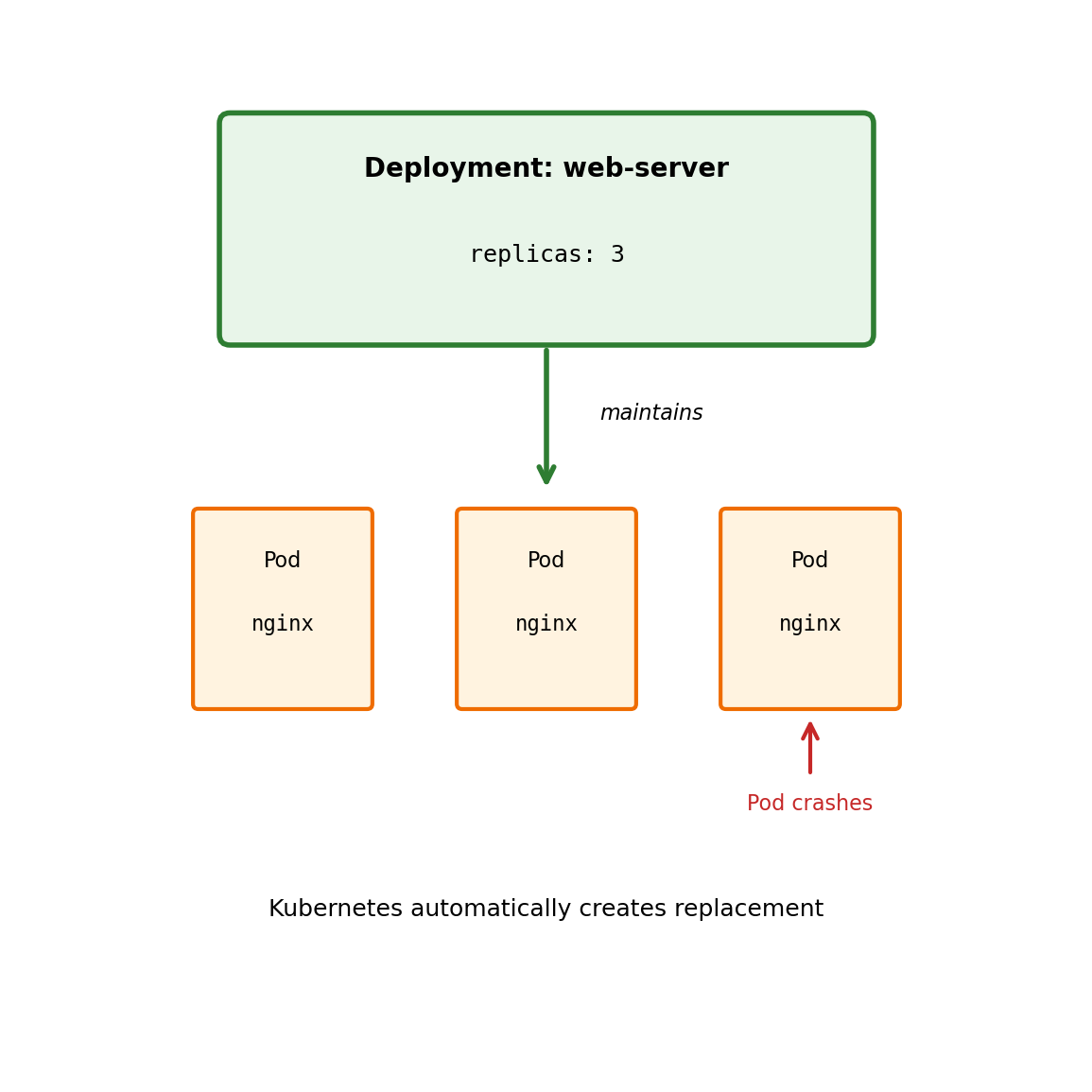

Deployments Manage Pod Lifecycles

You rarely create pods directly. Instead, you create a Deployment.

A Deployment declares:

- What container image to run

- How many replicas (pod instances)

- Resource requirements

- Update strategy

Kubernetes ensures reality matches the declaration:

- Pod crashes → Deployment creates a replacement

- Node fails → Pods rescheduled to other nodes

- You request 5 replicas → Kubernetes maintains exactly 5

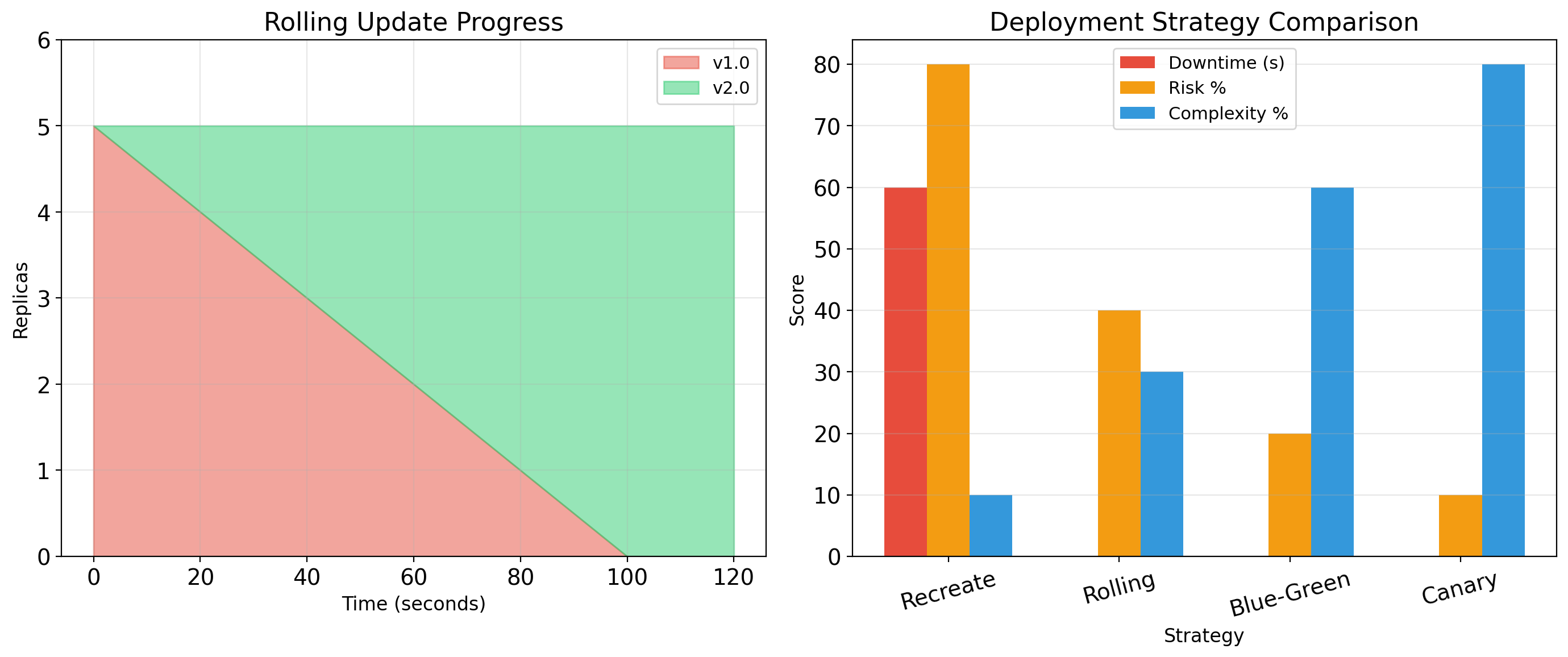

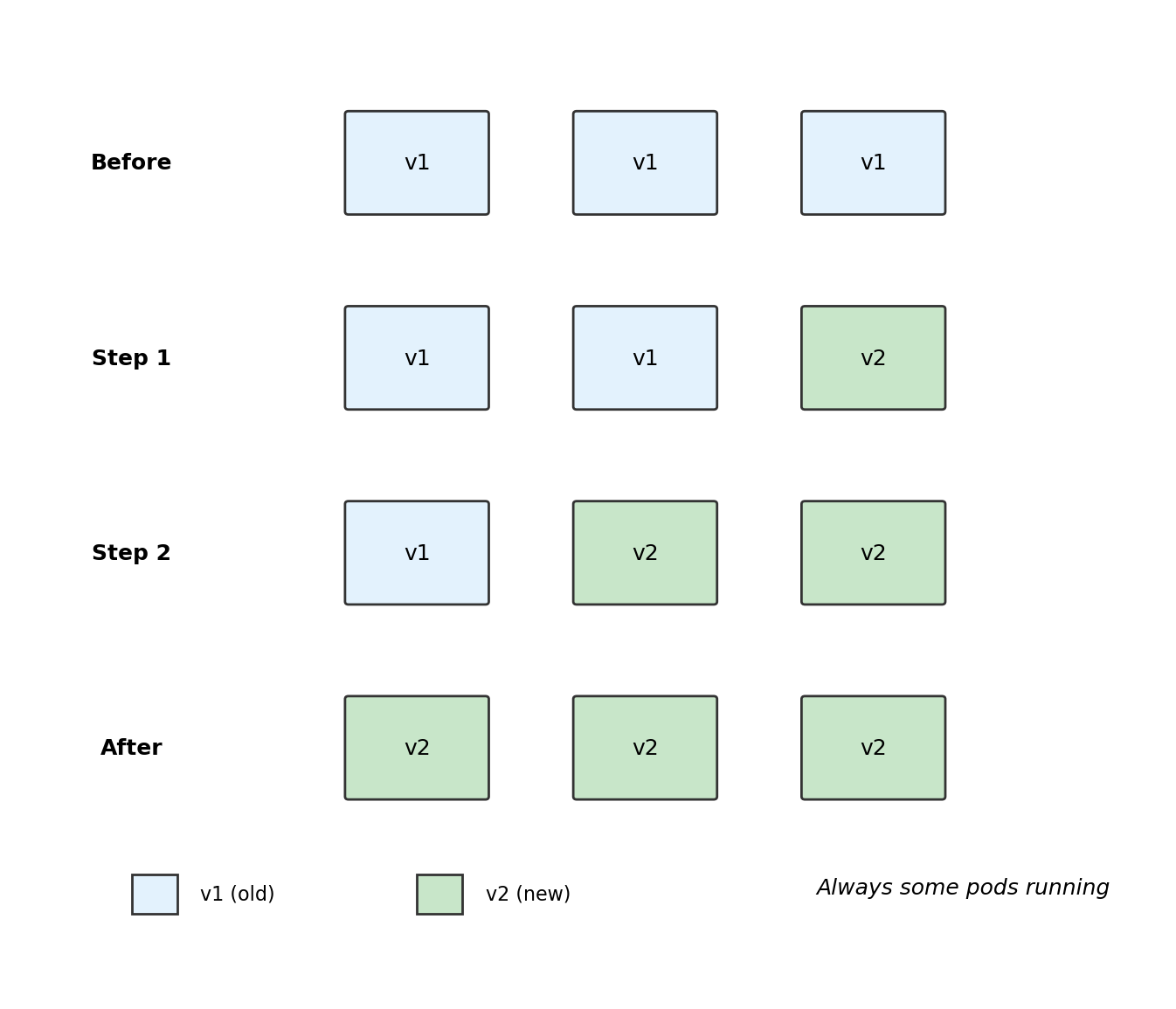

Deployments Handle Rolling Updates

When you update a Deployment (new image version), Kubernetes performs a rolling update:

- Create one new pod with new version

- Wait until it’s healthy

- Terminate one old pod

- Repeat until all pods are new version

No downtime

Some pods always running during the update. Traffic continues flowing.

Automatic rollback

If new pods fail health checks, Kubernetes stops the rollout. Old pods remain running.

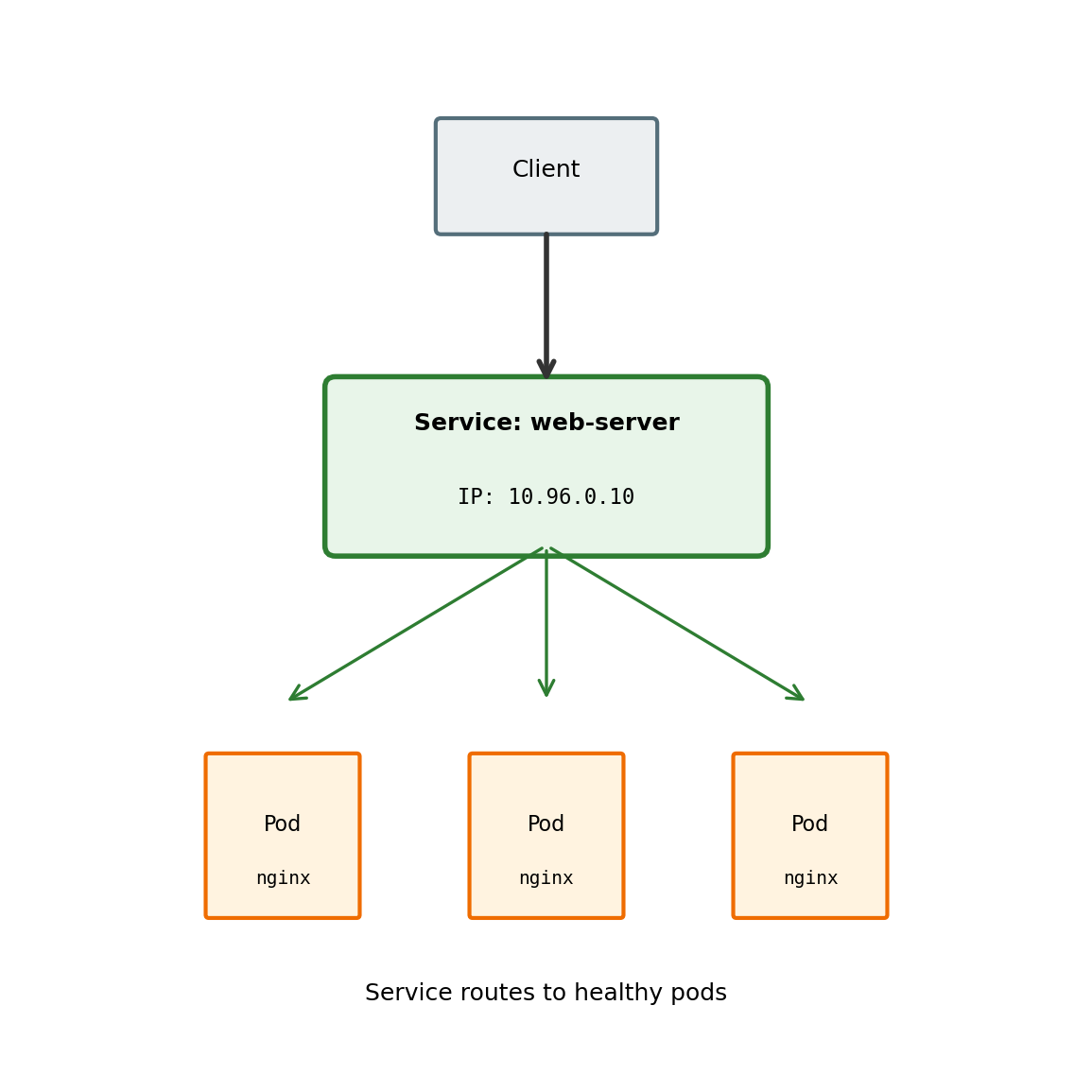

Services Provide Stable Network Endpoints

Pods have ephemeral IP addresses. A Service provides a stable endpoint.

A Service:

- Has a fixed cluster IP address

- Has a DNS name (e.g.,

web-server.default.svc.cluster.local) - Load balances traffic across matching pods

- Tracks pods using label selectors

When a pod dies and is replaced, the Service automatically routes to the new pod. Clients connect to the Service, not individual pods.

Service Types

Different Service types handle different access patterns:

ClusterIP (default)

Internal cluster IP only. Accessible within the cluster.

Used for: Internal services (databases, caches, internal APIs)

NodePort

Exposes service on each node’s IP at a static port (30000-32767).

Used for: Simple external access, development

Node IP:NodePort → Service → PodsLoadBalancer

Creates external load balancer (in cloud environments). Gets public IP.

Used for: Production external access

Public IP → Cloud LB → Service → PodsExternalName

Maps service to external DNS name. No proxying.

Used for: Referencing external services

For external traffic in production, LoadBalancer or an Ingress controller (HTTP routing) is typical.

Kubernetes Manages Configuration

ConfigMaps store non-sensitive configuration:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: app-config

data:

DATABASE_HOST: "db.default.svc"

LOG_LEVEL: "info"Secrets store sensitive data (base64 encoded, can be encrypted at rest):

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: db-credentials

type: Opaque

data:

password: cGFzc3dvcmQxMjM=Both can be mounted as files or exposed as environment variables in pods.

Why separate from images?

- Same image, different config per environment

- Rotate secrets without rebuilding images

- Configuration versioned separately from code

Injecting into pods:

containers:

- name: app

image: myapp:v1

envFrom:

- configMapRef:

name: app-config

- secretRef:

name: db-credentialsKubernetes handles mounting and updating configuration.

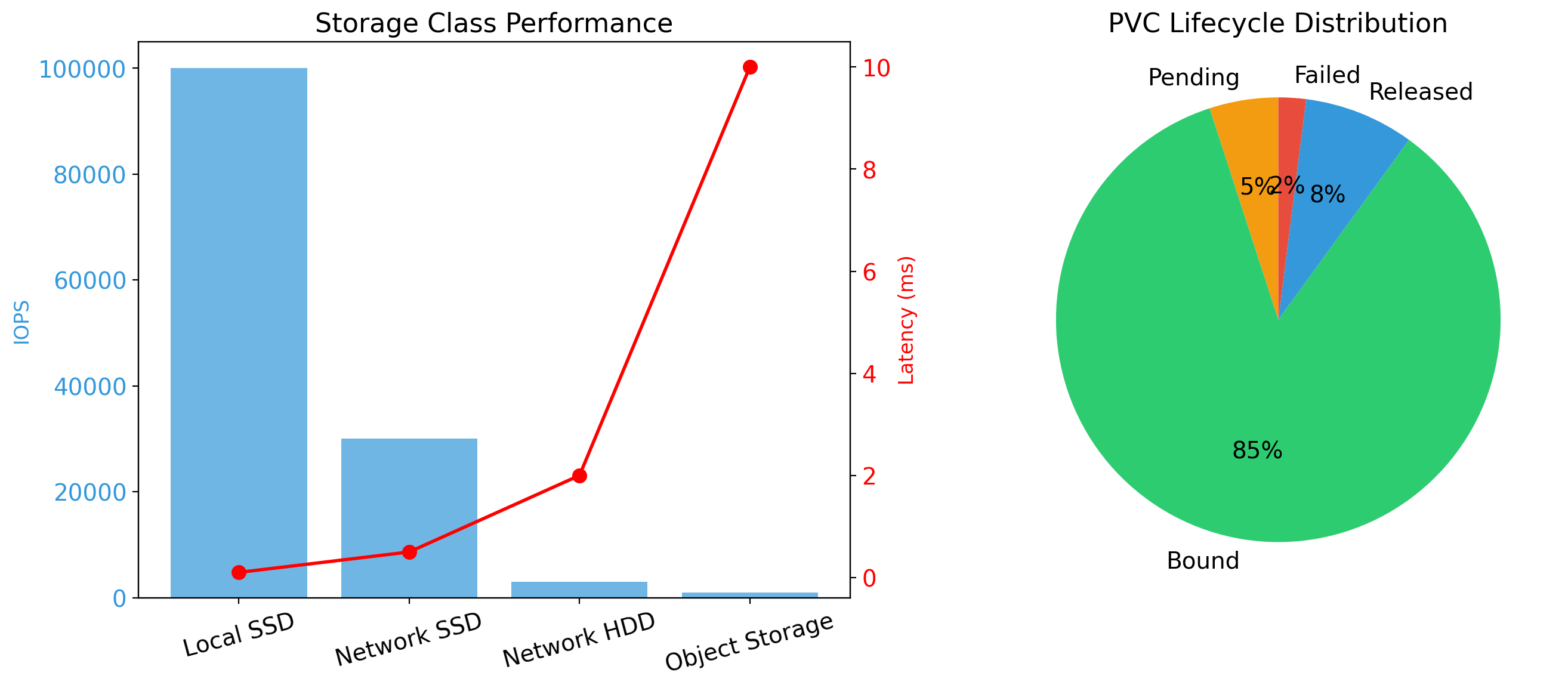

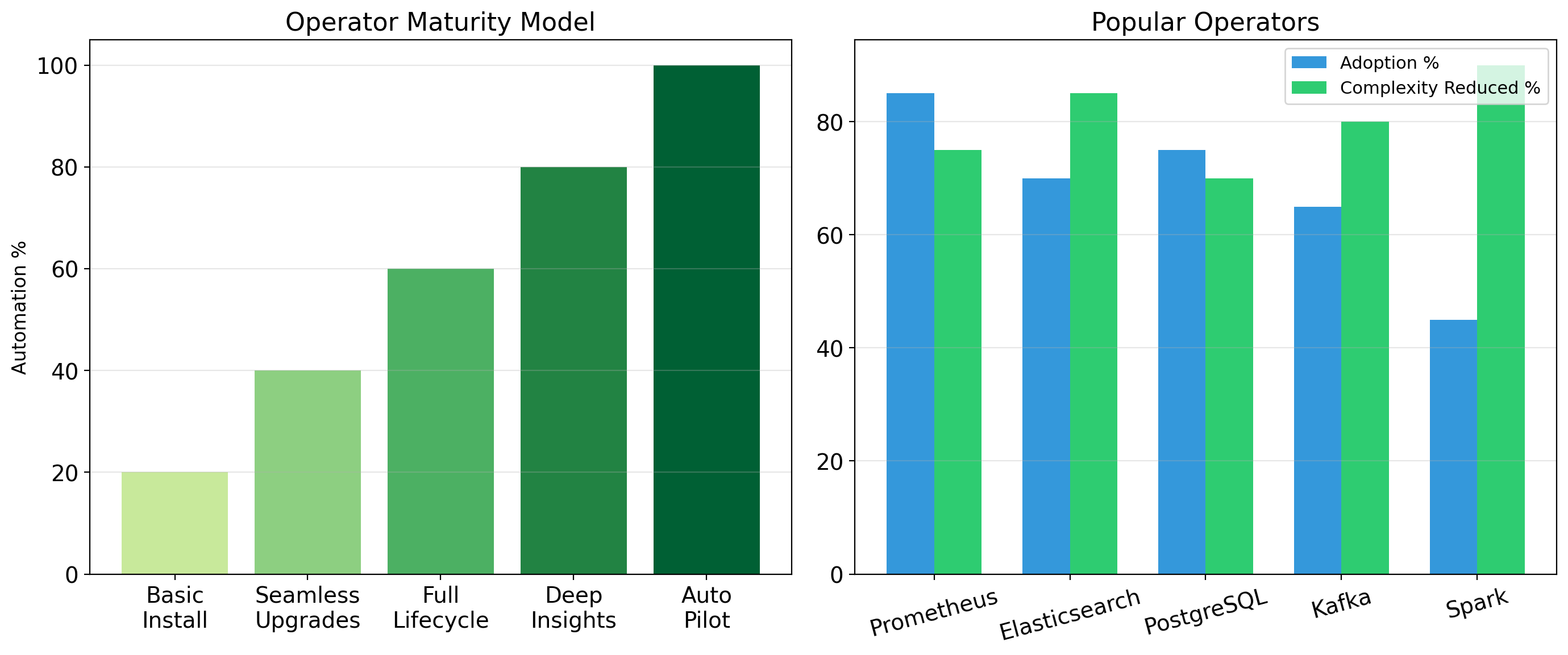

Kubernetes is Complex

The concepts covered here are foundational. Production Kubernetes involves much more:

- Ingress: HTTP routing, TLS termination

- NetworkPolicies: Firewall rules between pods

- PersistentVolumes: Storage management

- StatefulSets: For databases and stateful apps

- DaemonSets: One pod per node (logging, monitoring)

- RBAC: Access control

- Operators: Custom controllers

- Service mesh: Istio, Linkerd for advanced networking

Operating Kubernetes clusters requires significant expertise. Most organizations use managed services (EKS, GKE, AKS) to reduce operational burden.

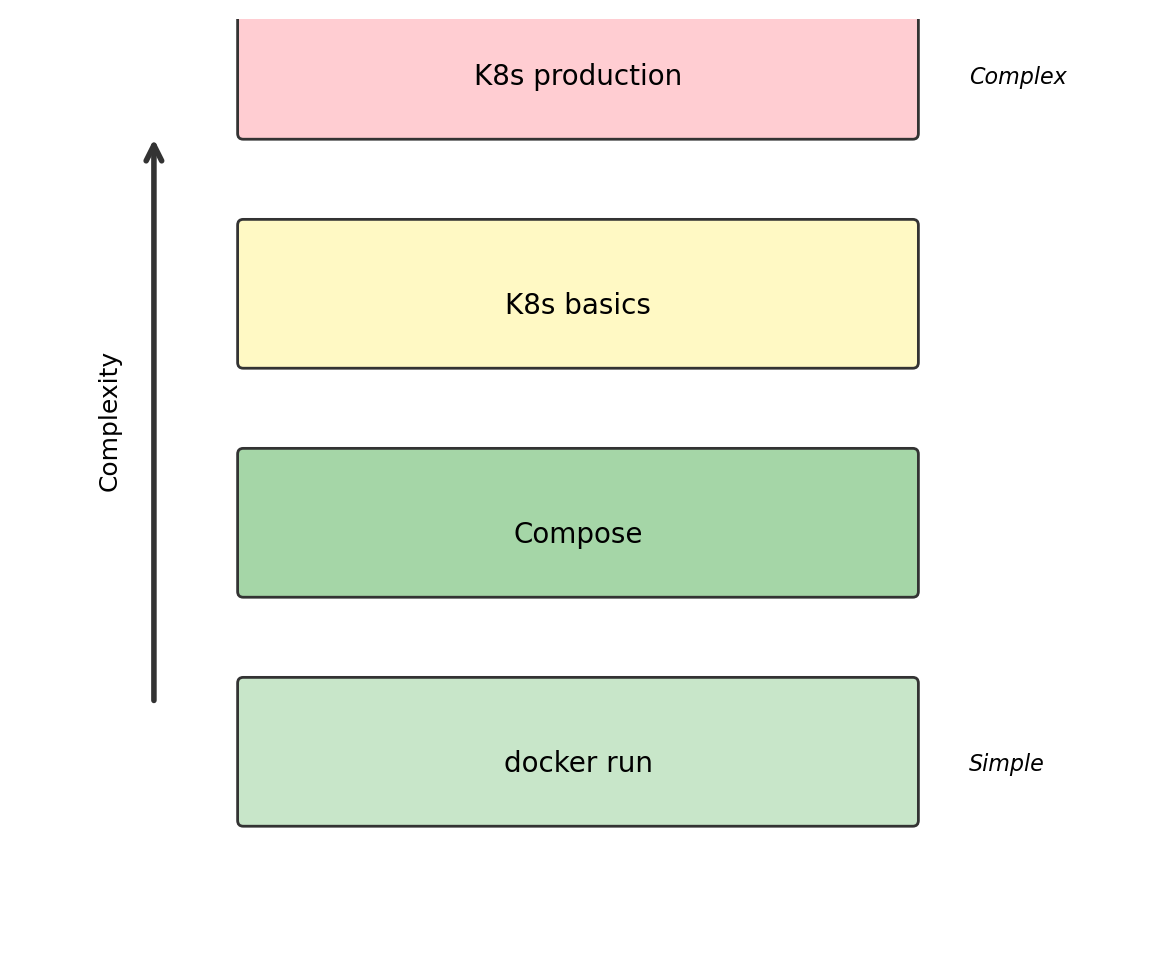

When to Use What

| Scenario | Tool |

|---|---|

| Single container, quick test | docker run |

| Multi-container, local development | Docker Compose |

| Multi-container, CI/CD testing | Docker Compose |

| Small-scale production, single host | Docker Compose (with monitoring) |

| Production requiring HA, scaling | Kubernetes (managed) |

| Large-scale, complex microservices | Kubernetes |

Start simple. Compose is sufficient for many production workloads. Add Kubernetes complexity when you need its capabilities—not before.

Managed services reduce burden. EKS, GKE, AKS handle control plane operations. You focus on deploying workloads, not maintaining clusters.

The concepts transfer. Understanding pods, deployments, and services helps even if you use AWS ECS or another platform. The problems are the same; the solutions are similar.

Kubernetes Concepts Summary

Cluster

Set of machines managed as a unit. Control plane + worker nodes.

Pod

Smallest deployable unit. Usually one container. Ephemeral—comes and goes.

Deployment

Declares desired state. Maintains replica count. Handles rolling updates.

Service

Stable network endpoint for pods. Load balances across replicas. Provides DNS name.

ConfigMap / Secret

Externalized configuration. Injected into pods as env vars or files.

Node

Worker machine in the cluster. Runs kubelet, container runtime, pods.

These concepts appear in various forms across orchestration platforms. Understanding them prepares you for working with container infrastructure regardless of the specific tool.