Cloud Infrastructure

EE 547 - Unit 3

Spring 2026

Outline

AWS Foundations

- Regions, availability zones, and global footprint

- Service endpoints and the API model

- Virtual machines on demand

- Instance types, AMIs, and lifecycle

- Security groups as stateful firewalls

Identity and Access Management

- Principals, policies, and ARNs

- Roles and temporary credentials

- Instance profiles for EC2

Storage, Networking, and Services

- Object storage vs block storage

- Buckets, keys, and the flat namespace

- VPCs, subnets, and route tables

- Public vs private subnets

- Security groups and load balancers

- Managed databases, queues, and serverless

- Pay-per-use economics and cost awareness

Cloud Infrastructure

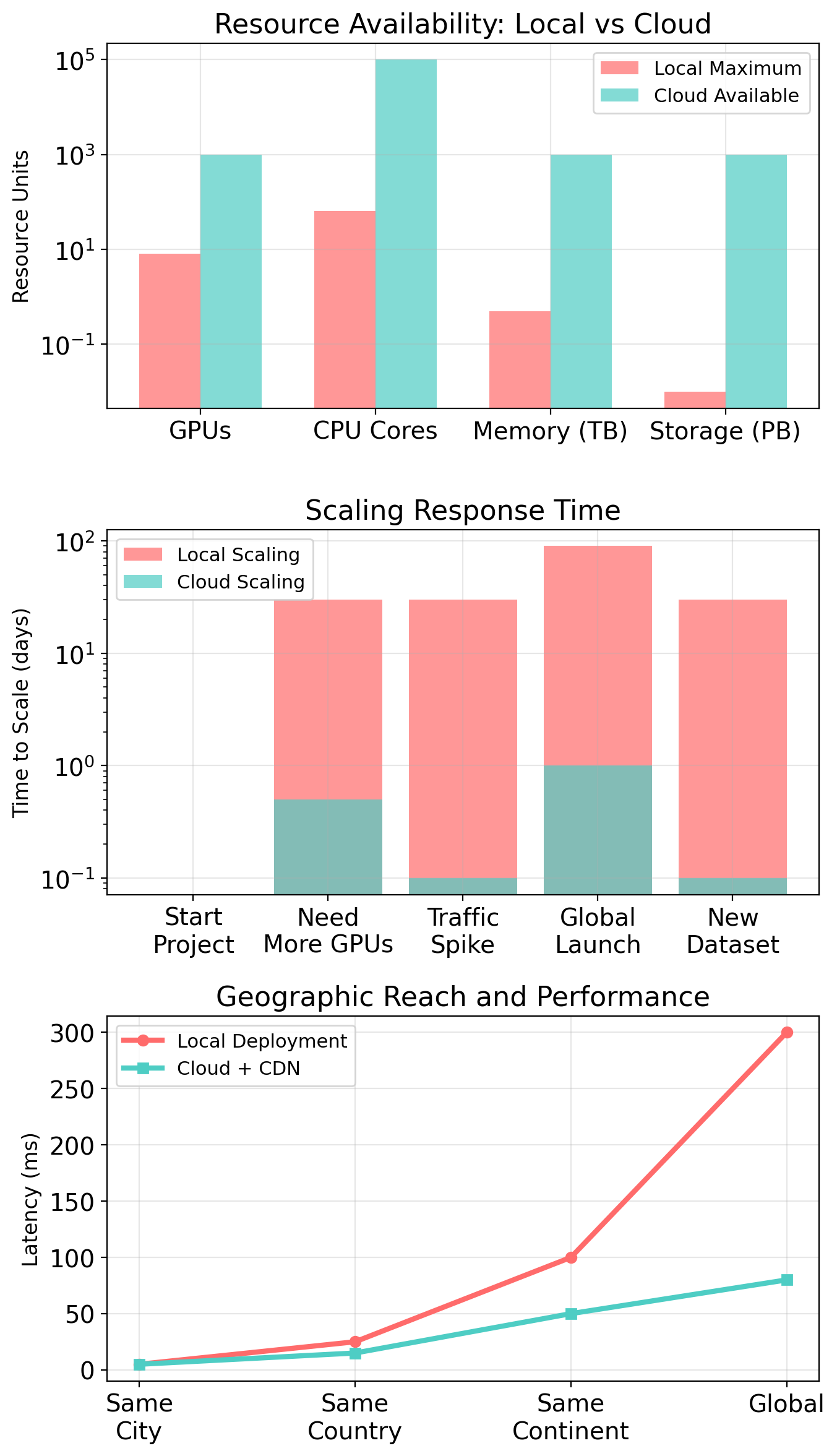

When Local Resources Aren’t Enough

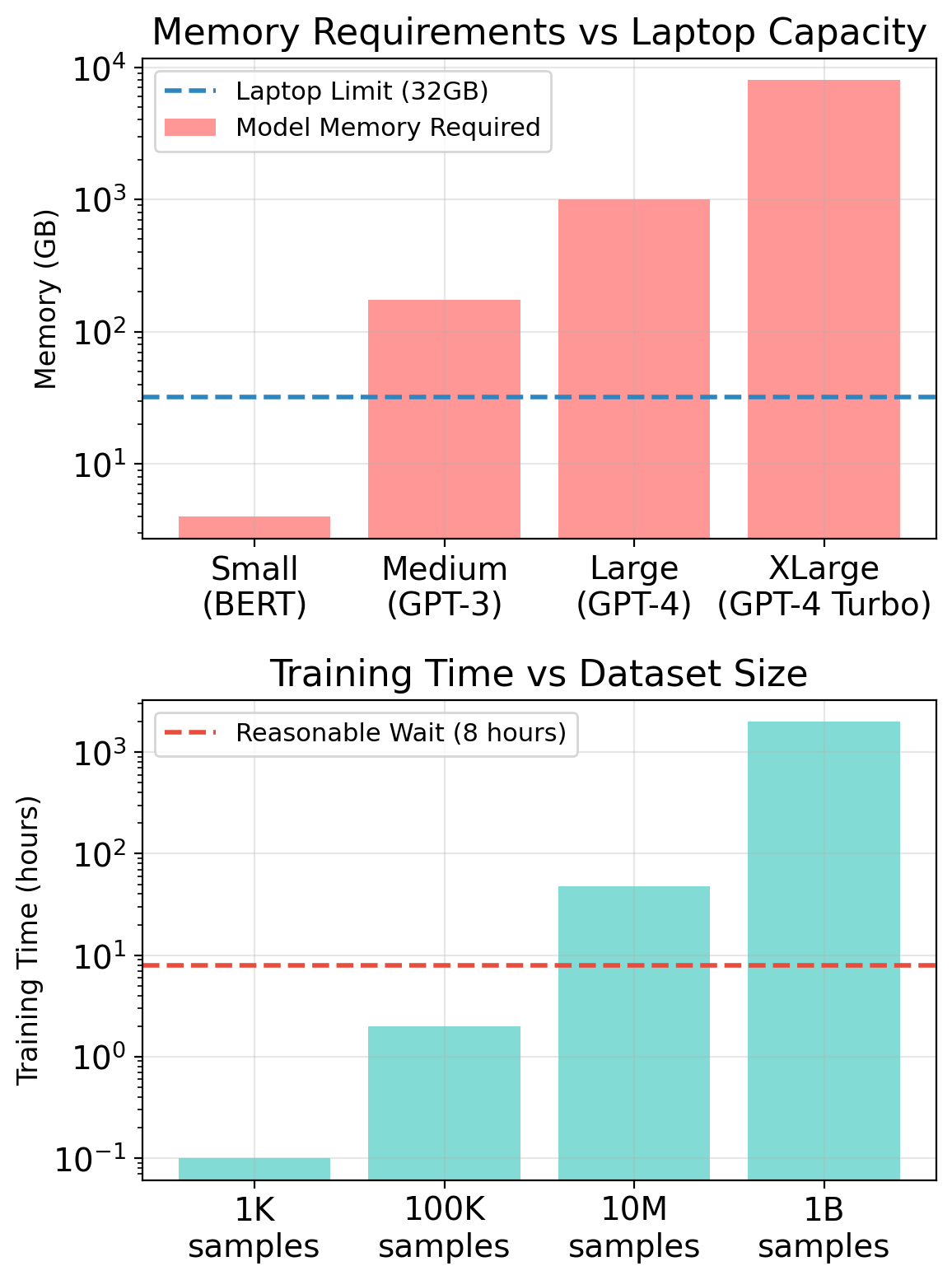

Your development machine is a single point of failure with fixed capacity.

What one machine provides

| Resource | Typical Range |

|---|---|

| RAM | 16–64 GB |

| CPU cores | 8–16 |

| Storage | 1–2 TB SSD |

| GPU VRAM | 0–24 GB |

| Network | Your ISP |

| Availability | When it’s on |

This is enough for development. It’s not enough for production.

Where single machines fail

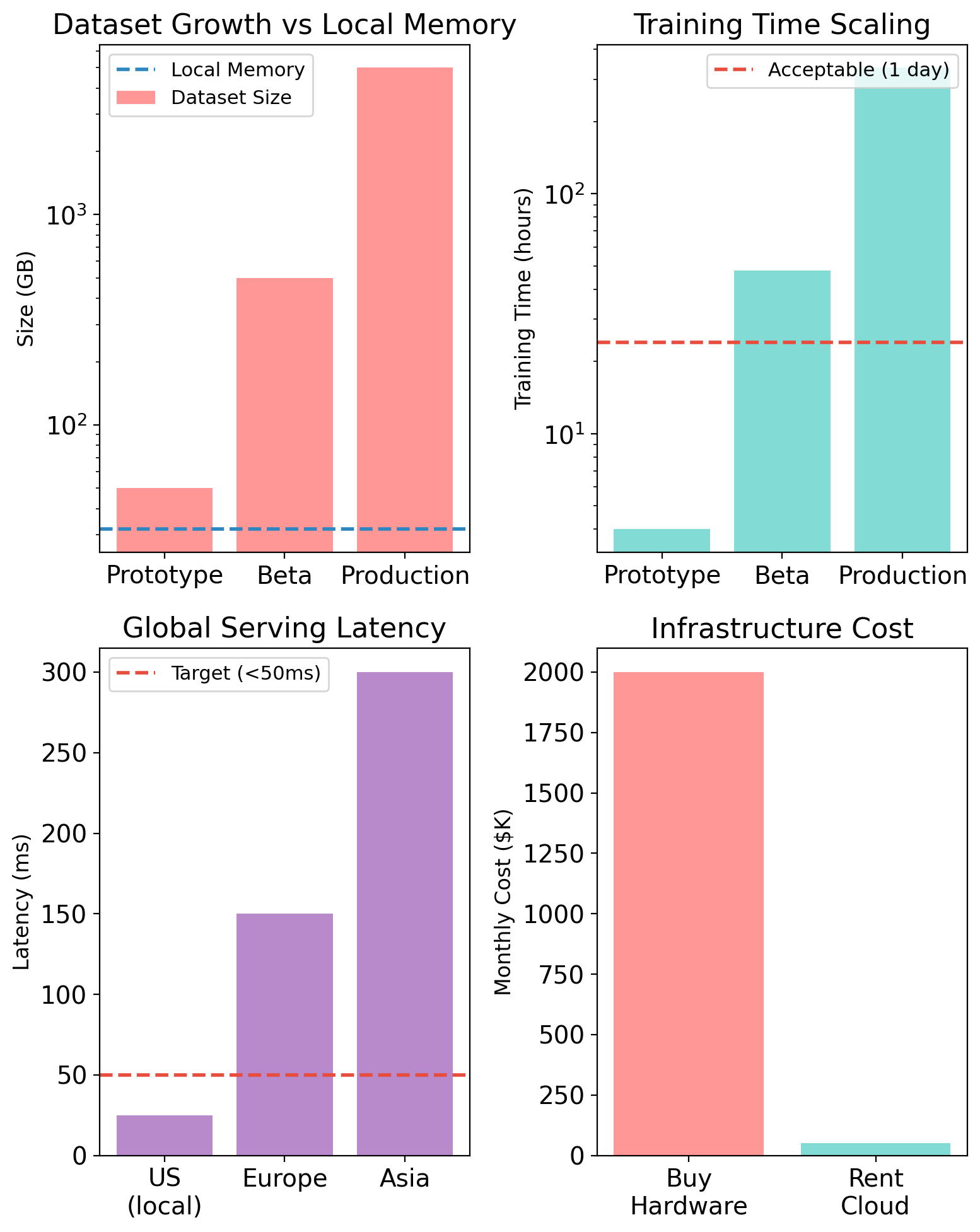

Scale: Dataset exceeds memory. Model exceeds GPU. Traffic exceeds capacity. You can’t add more hardware to a laptop.

Reliability: Hardware fails. Power goes out. Your machine restarts for updates. One machine means one failure domain.

Geography: Users in Tokyo experience 150ms latency to your server in Los Angeles. Physics doesn’t negotiate.

Elasticity: Traffic spikes 10× during launch. You either over-provision (waste money) or under-provision (drop requests).

These problems share a solution: access to infrastructure you don’t own.

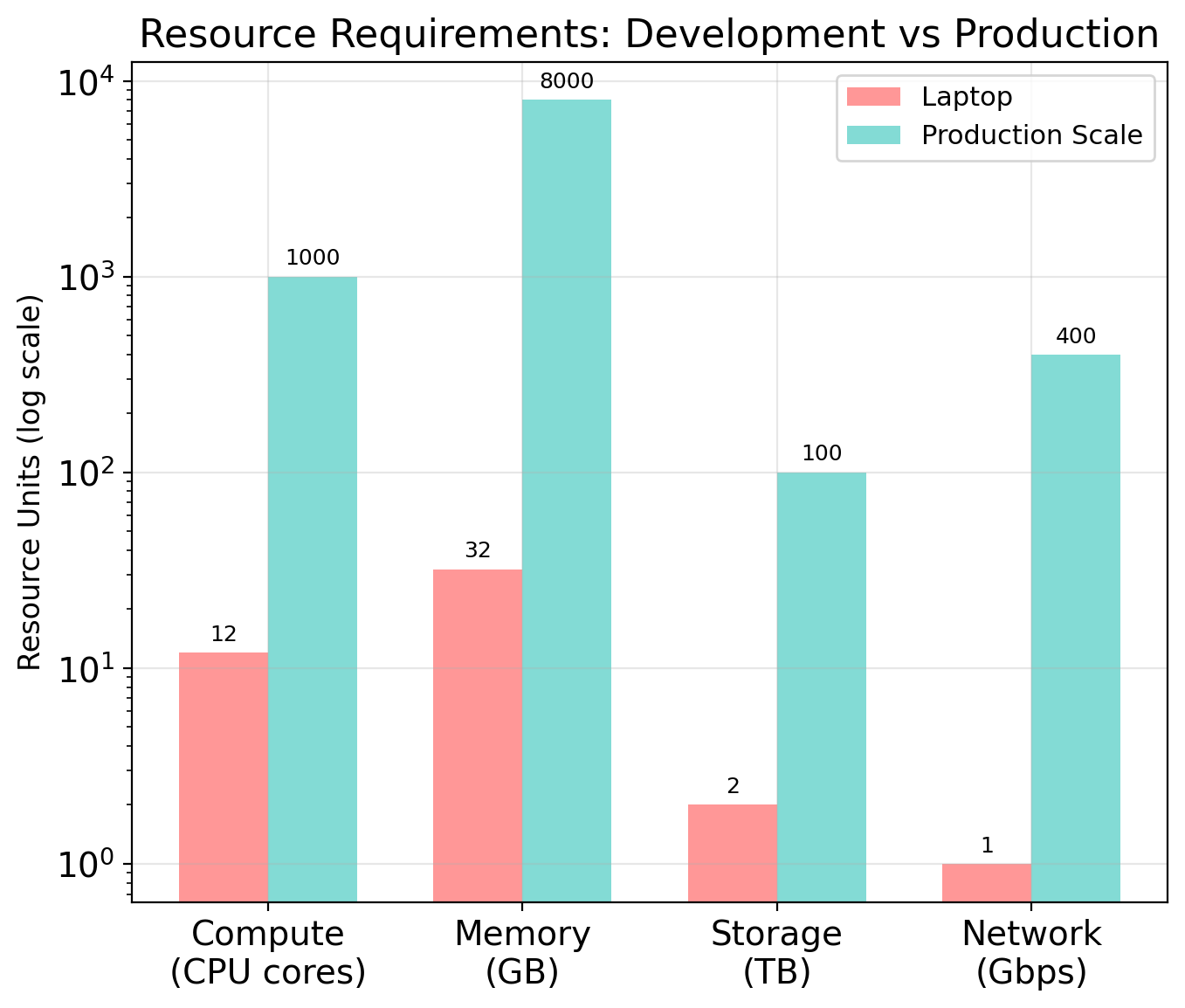

Infrastructure as a Service

Someone else operates the hardware. You rent capacity.

Operating infrastructure requires:

- Physical hardware (servers, storage, networking)

- Facilities (power, cooling, physical security)

- Staff (installation, maintenance, monitoring)

- Capacity planning (lead times measured in months)

These costs are largely fixed. A datacenter serving 100 users costs nearly as much as one serving 10,000.

Cloud model:

Providers operate infrastructure at massive scale, amortize fixed costs across many customers.

You pay for what you use. Capacity appears on demand.

Major providers:

- Amazon Web Services (AWS)

- Microsoft Azure

- Google Cloud Platform

Same underlying model, different APIs. This course uses AWS.

Why Hyperscalers Exist

The enterprise infrastructure problem

- Provision for peak load → idle most of the time

- Retail: 10× capacity for Black Friday

- Tax software: 50× capacity in April

- Measured utilization: 15–25% average

- 3–5 year hardware lifecycle locks in capacity

Expertise gap

- Network, storage, security, DBA specialists

- $150K–$300K salaries, on-call coverage

- 50-person startup can’t afford 10-person infra team

Hyperscaler economics

- AWS: ~2 million servers

Statistical multiplexing

- Your peak = someone else’s trough

- Pooled utilization: 60–70% vs enterprise 15–25%

Scale advantages

- Bulk purchasing: hundreds of thousands of servers/year

- Custom hardware, industrial power rates

- Automation amortized across millions of customers

- Thousands of engineers per domain

Pay-per-Use Changes Financial Risk

CapEx: locked in upfront

- Servers: $5K–$50K each

- Modest deployment: $500K–$5M before first customer

- Depreciates over 3–5 years regardless of use

- Lead time: weeks to months

- Forecast wrong → stranded capital or lost customers

OpEx: scales with usage

- Start at $0, pay per hour/second/request

- Use more → pay more; shut down → pay nothing

- Capacity adjusts in minutes

- Experiments are cheap to try and discard

| Scenario | CapEx | OpEx |

|---|---|---|

| Bought 50, need 20 | Pay for 50 | Pay for 20 |

| Bought 50, need 100 | Can’t serve | Scale to 100 |

| Project canceled | Stranded asset | Stop paying |

Why AWS?

Market position

- 30% market share (Q2 2025) — largest provider

- Azure: 20%, GCP: 13%

- First mover: S3 launched March 2006, EC2 August 2006

- 19 years of production operation

Maturity and stability

- 200+ services across compute, storage, networking, ML, etc.

- APIs versioned by date (S3:

2006-03-01— still works) - Backwards compatibility: old code keeps running

- Enterprise adoption: Netflix, Airbnb, NASA, FDA

Ecosystem

- Most extensive documentation and tutorials

- Largest community: Stack Overflow, forums, blogs

- Most third-party tools and integrations

- Broadest hiring market for AWS skills

For this course

- Skills transfer: concepts apply to Azure/GCP

- Industry standard: most likely to encounter professionally

- Deepest free tier for learning

- Best tooling for programmatic access (boto3, CLI)

AWS as a Platform

AWS provides access to infrastructure through services.

Each service encapsulates a specific capability:

| Service | Capability |

|---|---|

| EC2 | Virtual machines |

| S3 | Object storage |

| EBS | Block storage (virtual disks) |

| VPC | Virtual networks |

| IAM | Identity and access control |

| RDS | Managed relational databases |

| DynamoDB | Key-value database |

| Lambda | Function execution |

| SQS | Message queues |

~200+ services exist. They share common patterns: API access, regional deployment, metered billing.

API-Driven Infrastructure

Every AWS operation is an API call.

Creating an EC2 instance:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: ec2.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 ...

Action=RunInstances

&ImageId=ami-0abcdef1234567890

&InstanceType=t3.micro

&MinCount=1&MaxCount=1The response contains an instance ID—a handle to a running VM somewhere in AWS infrastructure.

Three interfaces to the same API:

Console — Web UI that constructs HTTP requests

CLI — Command-line tool that constructs HTTP requests

SDK — Library (Python, Go, etc.) that constructs HTTP requests

All three provide different ergonomics for the same underlying operations. The Console is convenient for exploration; the CLI and SDK enable automation.

Service Endpoints

Each service exposes an endpoint per region.

| Service | Region | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|

| EC2 | N. Virginia | ec2.us-east-1.amazonaws.com |

| EC2 | Ireland | ec2.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com |

| S3 | N. Virginia | s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com |

| IAM | (global) | iam.amazonaws.com |

The region in the endpoint determines where the request is processed and where resources are created.

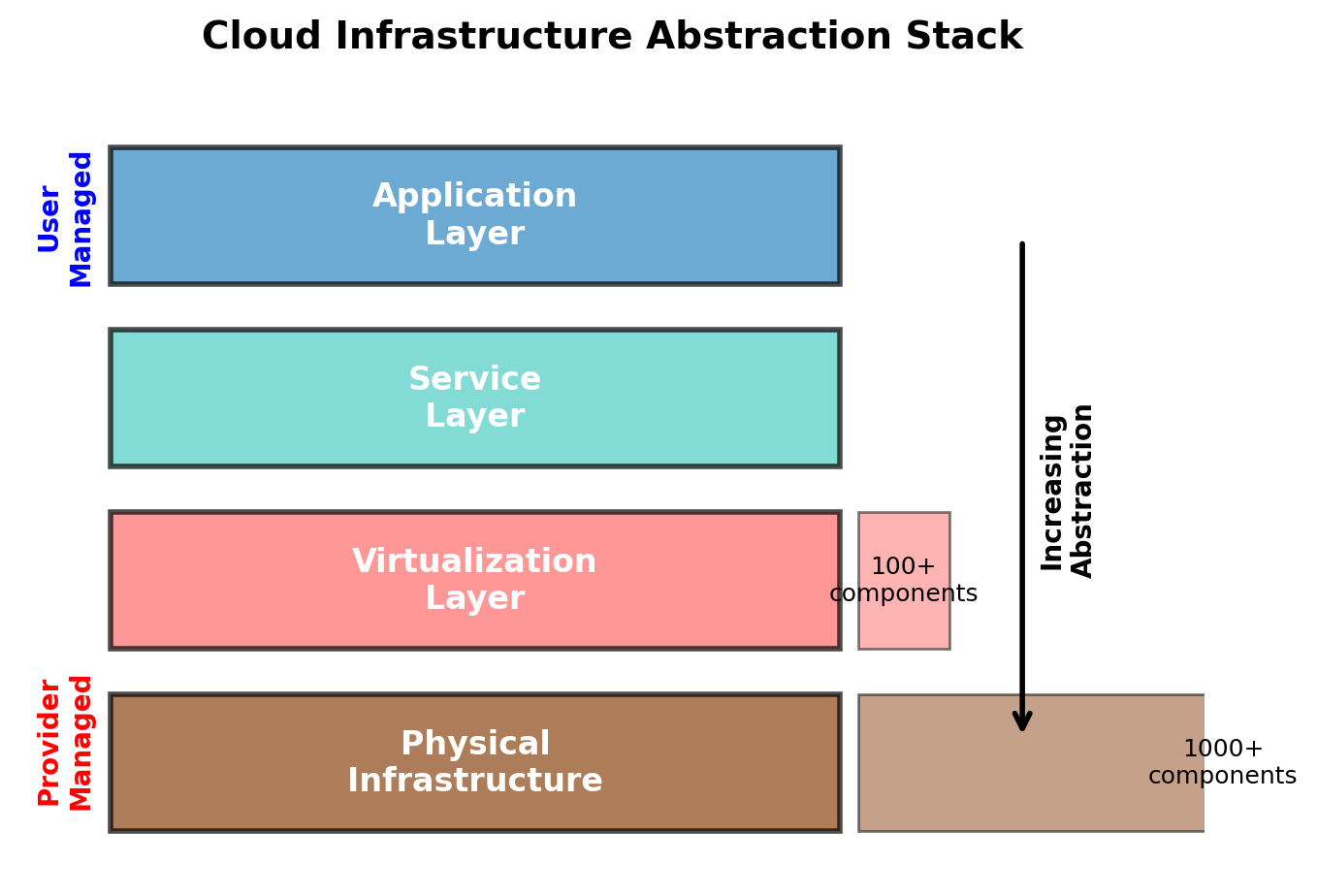

Abstraction Over Physical Infrastructure

AWS operates datacenters. You interact with abstractions over them.

What you specify:

- “A virtual machine with 2 CPUs and 8GB RAM”

- “A storage bucket for objects”

- “A PostgreSQL database with 100GB”

What AWS decides:

- Which physical server hosts your VM

- Which storage arrays hold your data

- When to migrate workloads for maintenance

Physical constraints still apply:

Latency — Data travels at finite speed. Virginia to Tokyo ≈ 90ms minimum round-trip.

Jurisdiction — Data stored in eu-west-1 physically resides in Ireland, subject to EU law.

Failure — Hardware fails. AWS handles many failure modes transparently; some propagate to your applications.

The abstraction hides operational complexity, not physical reality.

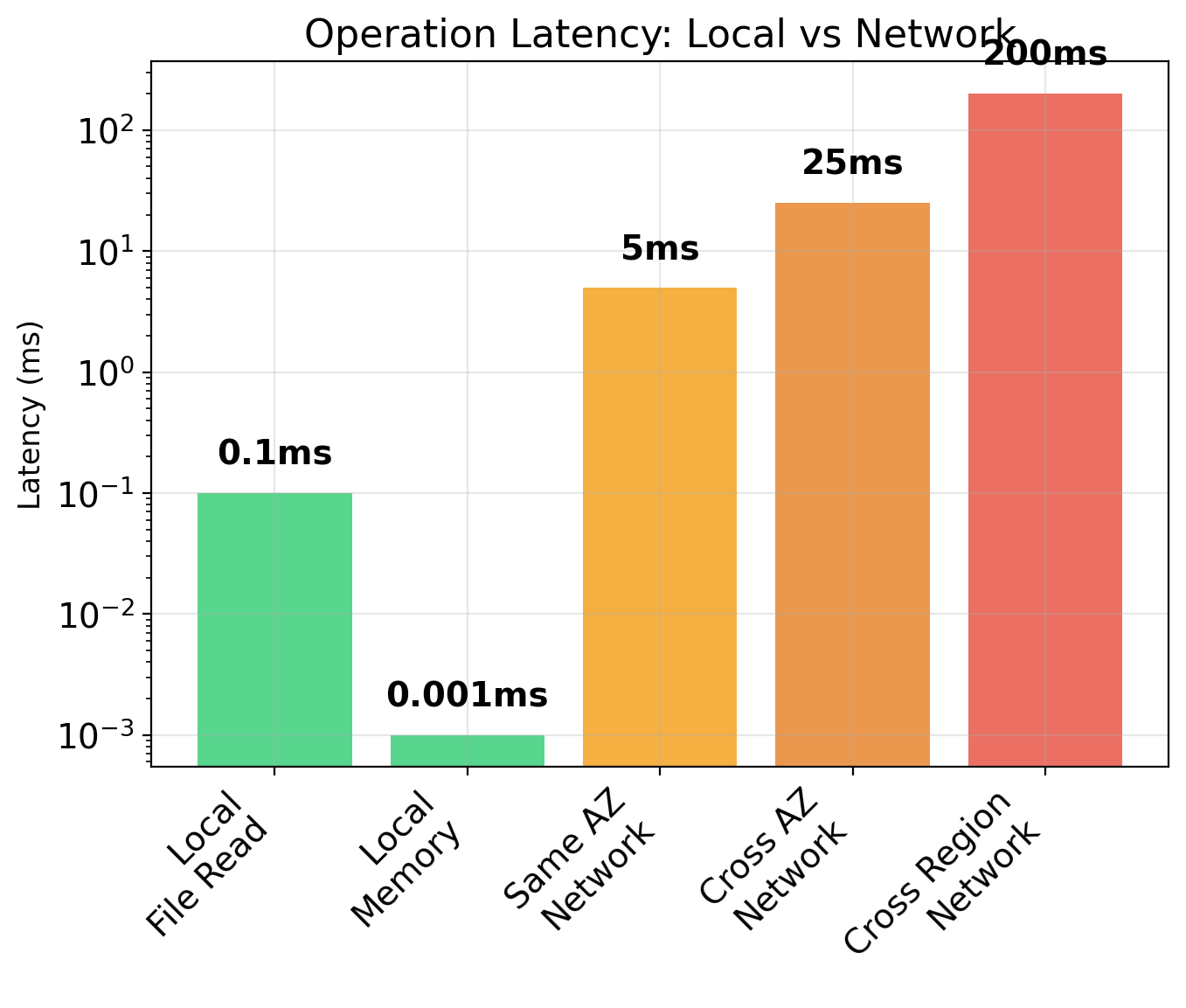

Network Latency Changes Everything

Local operations are fast. Network operations are not.

Orders of magnitude

| Operation | Latency |

|---|---|

| Memory access | 0.0001 ms |

| SSD read | 0.1 ms |

| Same-AZ network | 1–5 ms |

| Cross-AZ network | 5–20 ms |

| Cross-region | 50–200 ms |

What took nanoseconds now takes milliseconds. That’s 10,000× to 1,000,000× slower.

Practical impact

A web request that makes 10 database queries:

- Local SQLite: 10 × 0.1ms = 1ms total

- Same-AZ RDS: 10 × 3ms = 30ms total

- Cross-region: 10 × 100ms = 1 second total

Suddenly your “fast” code is slow. The algorithm didn’t change—the environment did.

Design responses:

- Batch operations (1 query returning 100 rows, not 100 queries)

- Cache aggressively (avoid repeated network calls)

- Co-locate data and compute (same AZ when possible)

Partial Failures Are Normal

On your laptop, things either work or they don’t. In distributed systems, things partially work.

Local failure model

Program crashes → everything stops. Out of memory → process dies. Disk full → all writes fail.

Failure is total and obvious. You fix it and restart.

Distributed failure model

- Database responds, but slowly (2 seconds instead of 20ms)

- S3 returns errors for some requests, not all

- One of five servers is unreachable

- Network drops 0.1% of packets

Failure is partial and subtle. Your system keeps running, but wrong.

Example: uploading a file

# Local: this either works or throws

with open('output.csv', 'w') as f:

f.write(data)

# S3: what if the network blips mid-upload?

s3.put_object(Bucket='b', Key='output.csv', Body=data)

# Did it succeed? Partially succeed? Need to retry?Patterns you’ll need:

- Timeouts: Don’t wait forever

- Retries with backoff: Try again, but not too aggressively

- Idempotency: Safe to retry without duplicating effects

- Health checks: Detect degraded components

These aren’t edge cases—they’re normal operation at scale.

AWS Global Infrastructure

Regions → Availability Zones → Data Centers

- 39 regions worldwide (2025)

- 100+ availability zones

- Each region: minimum 3 AZs

- Each AZ: one or more data centers

AZ isolation

- Separate power substations

- Independent cooling, networking

- 10–60 miles apart within region

- Single-digit millisecond latency between AZs

Failure containment

- Power outage hits one AZ, not the region

- Flood/fire affects one facility

- No shared fate between AZs

Data residency

- Data stays in region unless you move it

- EU regions for GDPR

- GovCloud for US government

- China regions isolated

Deploy across multiple AZs → survive AZ failure

Regions

AWS deploys infrastructure in multiple geographic locations called regions.

| Code | Location |

|---|---|

us-east-1 |

N. Virginia |

us-east-2 |

Ohio |

us-west-2 |

Oregon |

eu-west-1 |

Ireland |

eu-central-1 |

Frankfurt |

ap-northeast-1 |

Tokyo |

ap-southeast-1 |

Singapore |

sa-east-1 |

São Paulo |

Scale (2025):

- 34 regions, 108 availability zones

- Millions of active servers

- 100+ Tbps network backbone capacity

Regions are independent deployments.

Each region has its own:

- Compute and storage infrastructure

- Control plane (API endpoints)

- Network connectivity

Resources in us-east-1 don’t exist in eu-west-1. An outage in one region doesn’t directly affect others.

Region selection determines:

- Physical location of data and compute

- Latency to end users

- Applicable legal jurisdiction

- Available services (varies by region)

- Pricing (varies ~10-20%)

Availability Zones

Each region contains multiple Availability Zones (AZs)—physically separate datacenter facilities.

us-east-1 contains six AZs:

us-east-1a through us-east-1f

Physical characteristics:

- Separate buildings, miles apart

- Independent power (different substations)

- Independent cooling

- Independent network paths

Interconnected:

- Dedicated high-bandwidth fiber

- Sub-millisecond latency within region

Purpose: failure isolation

Datacenter failures happen—power outages, cooling failures, network cuts, fires.

AZs are designed so that a failure affecting one facility doesn’t affect the others (mostly). If us-east-1a loses power, us-east-1b through us-east-1f continue operating.

AZ names are per-account:

Your us-east-1a may map to a different physical facility than another account’s us-east-1a. AWS randomizes the mapping to distribute load across facilities.

For cross-account coordination, use AZ IDs: use1-az1, use1-az2, etc.

Resource Placement

Different AWS resources exist at different scopes within this hierarchy.

Resource Scope

Global

Exist once, accessible everywhere:

- IAM users and roles

- Route 53 DNS zones

- CloudFront distributions

These resources have no region. IAM policies apply across all regions.

Regional

Exist in one region, span AZs within that region:

- S3 buckets

- VPCs

- Lambda functions

- DynamoDB tables

Data is automatically replicated across AZs for durability.

Per-AZ

Exist in a specific AZ:

- EC2 instances

- EBS volumes

- Subnets

An EC2 instance runs on physical hardware in one AZ. An EBS volume stores data on drives in one AZ.

Placement constraint: Per-AZ resources can only attach to other resources in the same AZ. An EBS volume in us-east-1a cannot attach to an EC2 instance in us-east-1b.

Services Compose Through APIs

Your application calls AWS services through their APIs. Services also call each other—an EC2 instance reading from S3, a Lambda function writing to DynamoDB. All API calls are authenticated and authorized through IAM.

Platform Model

What AWS provides:

- Physical infrastructure (datacenters, hardware, networking)

- Abstraction layer (services, APIs)

- Operational management (maintenance, failures, capacity)

- Geographic distribution (regions, availability zones)

What you provide:

- Configuration (what resources, where, how connected)

- Application code (runs on the infrastructure)

- Access policies (who can do what)

The API contract:

You describe desired state through API calls. AWS materializes that state on physical infrastructure.

RunInstances → VM running on some server

CreateBucket → Storage allocated on some drives

CreateDBInstance → Database on some hardwareThe mapping from logical resource to physical infrastructure is AWS’s responsibility. Your responsibility is understanding what the logical resources provide and how they compose.

Compute: EC2

Virtual Machines as a Service

EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) provides virtual machines.

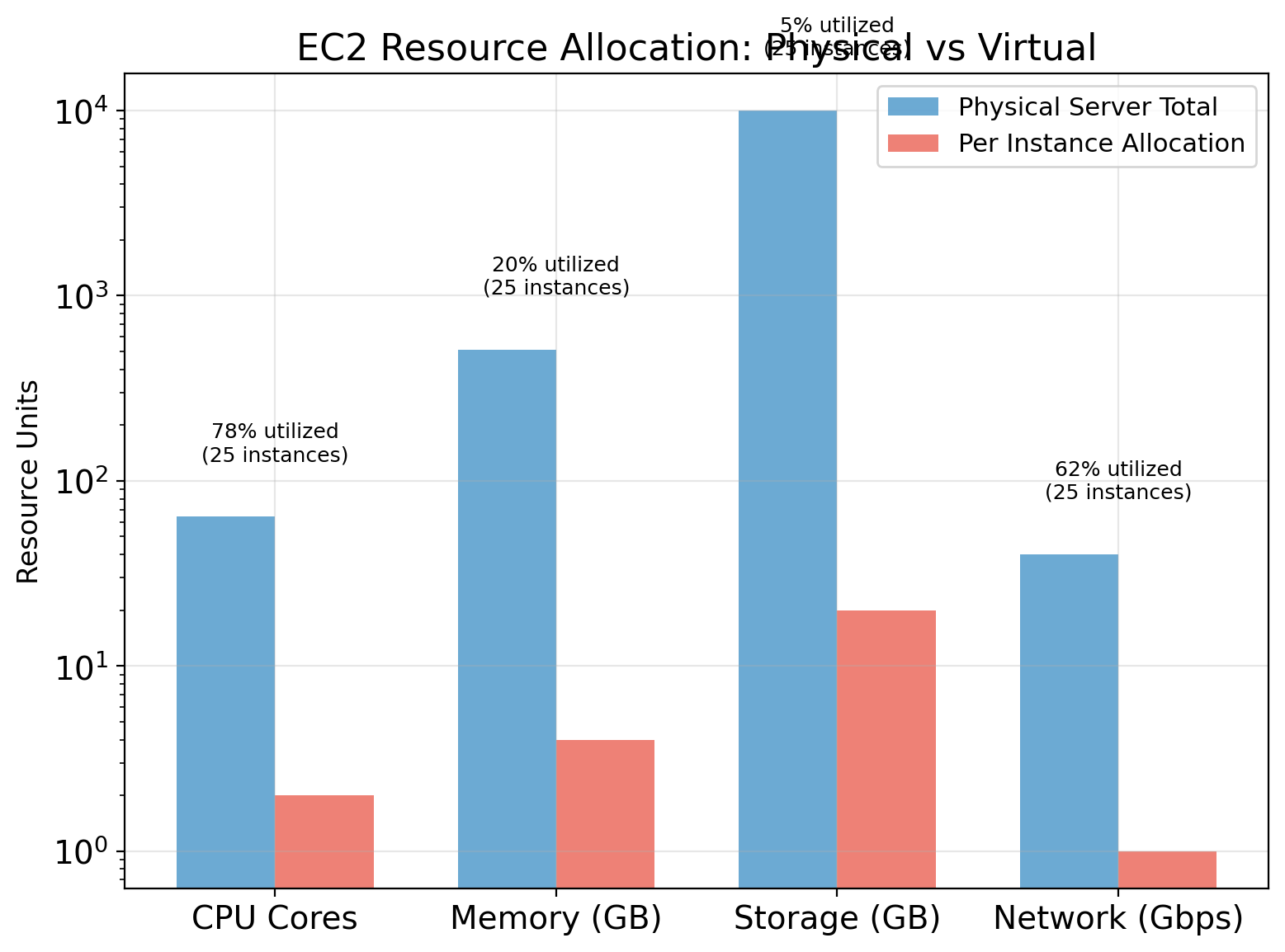

A physical server in an AWS datacenter runs a hypervisor. The hypervisor partitions hardware resources—CPU cores, memory, network bandwidth—and presents them to multiple virtual machines as if each had dedicated hardware.

What you receive:

- Virtualized CPU cores

- Allocated memory

- Virtual network interface

- Block device for storage

From inside the VM, this looks like a physical machine. The OS sees CPUs, RAM, disks, network interfaces.

What remains with AWS:

- Physical server selection and placement

- Hypervisor operation

- Hardware failure handling

- Physical network infrastructure

- Datacenter operations

You specify what you want. AWS decides which physical server provides it.

The Hypervisor Layer

Multiple EC2 instances share a physical server. The hypervisor enforces isolation—one instance cannot access another’s memory or see its network traffic. From each instance’s perspective, it has dedicated hardware.

Instance Types Represent Resource Profiles

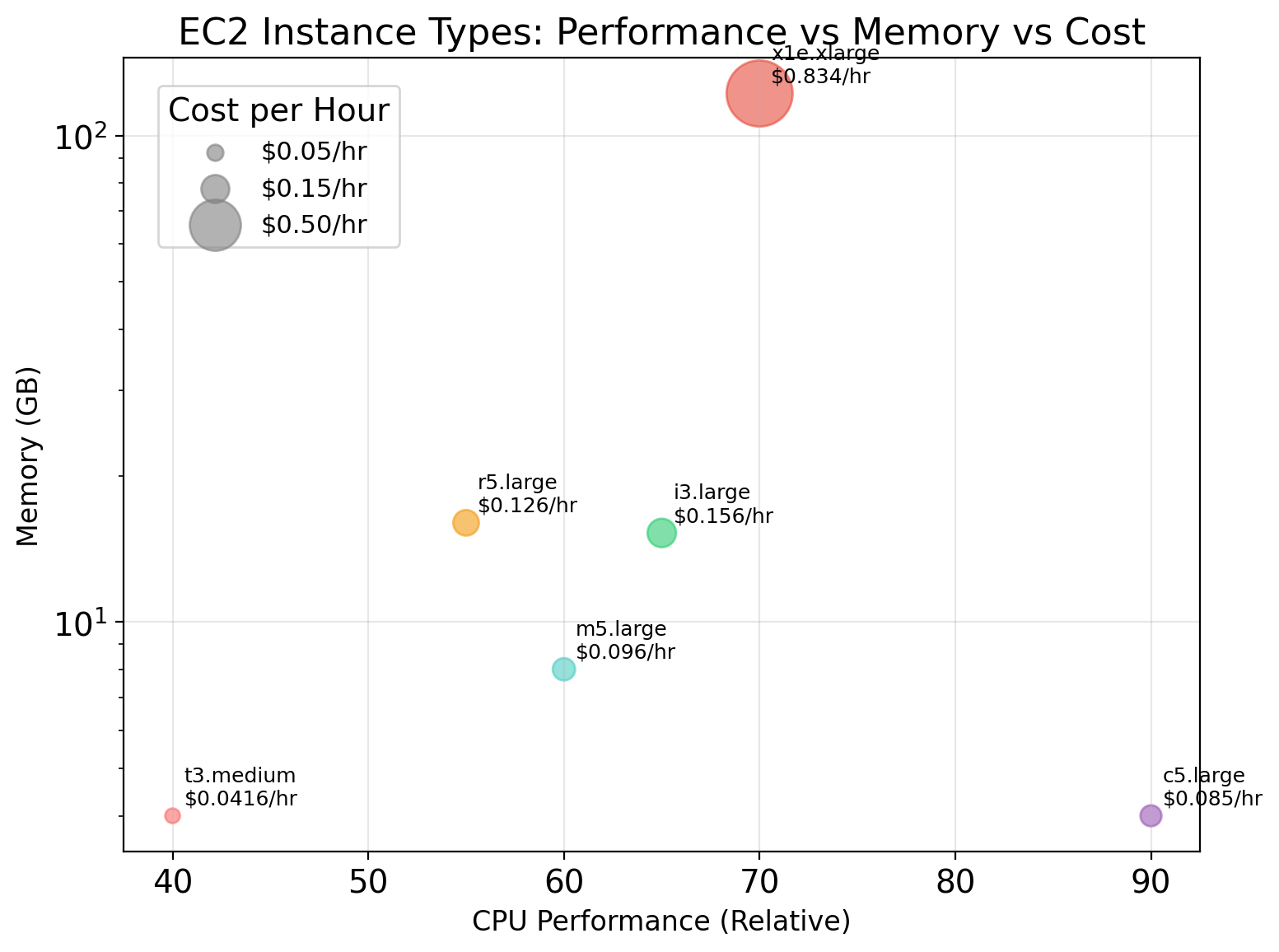

EC2 offers many instance types—different allocations of CPU, memory, storage, and network.

Naming convention: {family}{generation}.{size}

- Family: optimized for a workload category

- Generation: hardware revision (higher = newer)

- Size: scale within the family

| Type | vCPUs | Memory | Network | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t3.micro | 2 | 1 GB | Low | Development, light workloads |

| t3.large | 2 | 8 GB | Low-Mod | Small applications |

| m5.large | 2 | 8 GB | Moderate | Balanced workloads |

| m5.4xlarge | 16 | 64 GB | High | Larger applications |

| c5.4xlarge | 16 | 32 GB | High | Compute-intensive |

| r5.4xlarge | 16 | 128 GB | High | Memory-intensive |

Instance Families Target Different Workloads

General purpose (t3, m5):

Balanced CPU-to-memory ratio. Suitable for most workloads that don’t have extreme requirements in either dimension.

- m5: consistent performance

- t3: burstable (accumulates CPU credits when idle)

Compute optimized (c5):

High CPU-to-memory ratio. For workloads that are CPU-bound: batch processing, scientific modeling, video encoding.

c5.4xlarge: 16 vCPUs, 32 GB memory (2:1 ratio)

Memory optimized (r5, x1):

High memory-to-CPU ratio. For workloads that keep large datasets in memory: in-memory databases, caching, analytics.

r5.4xlarge: 16 vCPUs, 128 GB memory (1:8 ratio)

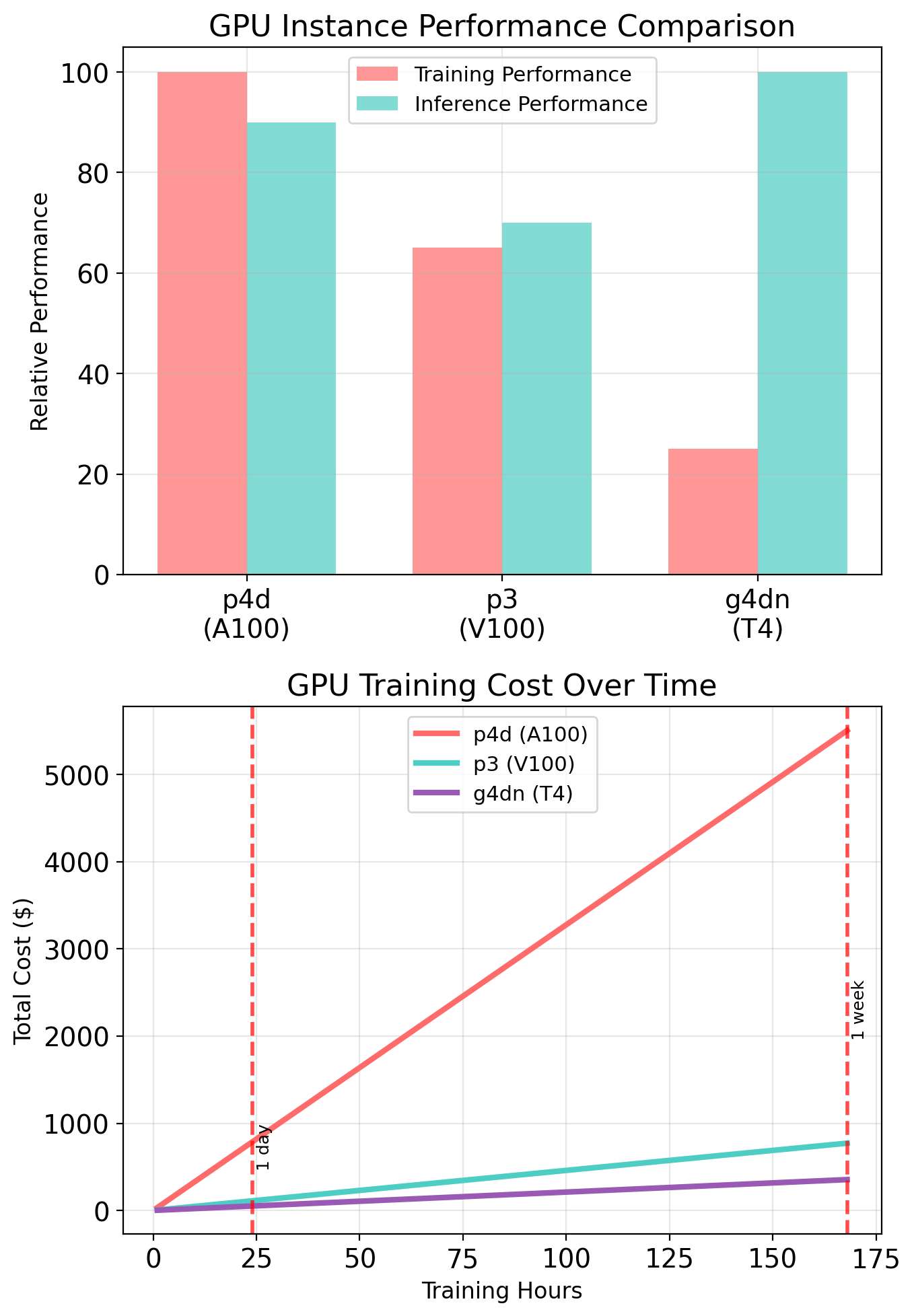

GPU instances (p3, g4):

Include NVIDIA GPUs. For ML training, inference, graphics rendering.

p3.2xlarge: 8 vCPUs, 61 GB, 1× V100 GPU

Storage optimized (i3, d2):

High sequential I/O. For data warehousing, distributed filesystems.

Burstable Instances (t3 Family)

The t3 family uses a CPU credit model.

How it works:

- Each t3 size has a baseline CPU utilization

- When below baseline, instance accumulates credits

- When above baseline, instance spends credits

- Credits exhausted → throttled to baseline

| Type | Baseline | Credits/hour |

|---|---|---|

| t3.micro | 10% | 6 |

| t3.small | 20% | 12 |

| t3.medium | 20% | 24 |

| t3.large | 30% | 36 |

t3.micro can burst to 100% CPU, but sustained usage above 10% depletes credits.

Implications:

Good for:

- Variable workloads with idle periods

- Development and testing

- Small services with occasional spikes

Not good for:

- Sustained high CPU usage

- Predictable heavy computation

- Latency-sensitive under load

For sustained workloads, m5 or c5 provide consistent performance without the credit system.

Course work: t3.micro is sufficient and free-tier eligible.

An Instance is Assembled from Components

Launching an EC2 instance combines several configuration elements:

Each component contributes a different aspect: what software runs, what resources it has, how it’s accessed, what network it’s on, what it can do.

Component Roles

| Component | What It Determines | When Specified |

|---|---|---|

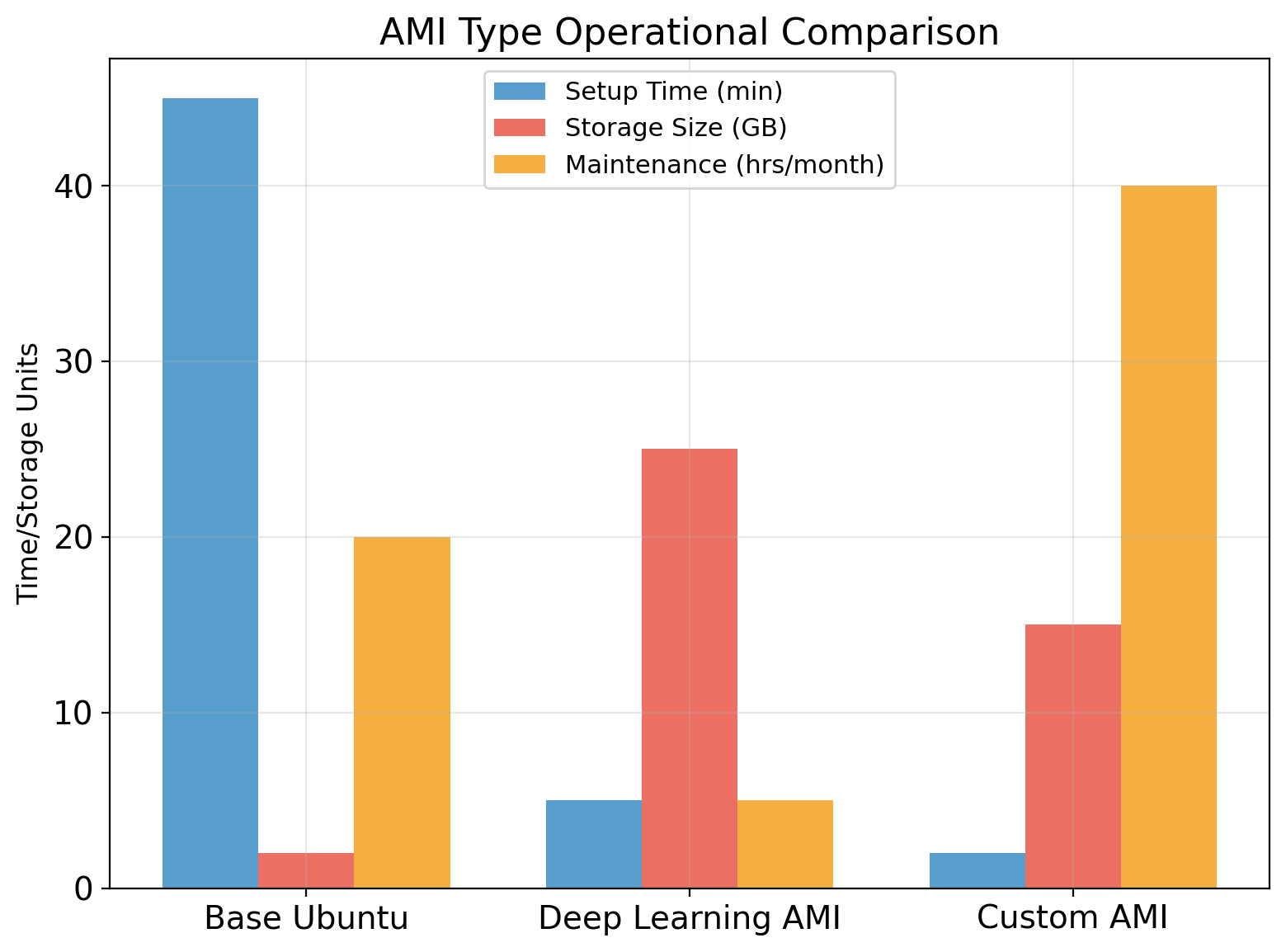

| AMI | Operating system, pre-installed software | At launch (immutable) |

| Instance type | CPU, memory, network capacity | At launch (can change when stopped) |

| Key pair | SSH authentication | At launch (cannot change) |

| Security group | Allowed inbound/outbound traffic | At launch (can modify later) |

| Subnet | VPC, Availability Zone, IP range | At launch (immutable) |

| IAM role | Permissions for AWS API calls | At launch (can change) |

| EBS volumes | Persistent storage | At launch or attach later |

AMI (Amazon Machine Image):

Template containing OS and software. AWS provides Amazon Linux, Ubuntu, Windows. AMI IDs are region-specific—the same Ubuntu version has different IDs in different regions.

Security Groups Control Traffic

A security group is a stateful firewall applied to instances.

Inbound rules specify what traffic can reach the instance:

Type Port Source

─────────────────────────────

SSH 22 0.0.0.0/0

HTTP 80 0.0.0.0/0

HTTPS 443 0.0.0.0/0

PostgreSQL 5432 10.0.0.0/16

Custom 8080 sg-0abc1234Each rule: protocol, port range, source (CIDR or security group).

Default inbound: deny all

Outbound rules specify what traffic the instance can send:

Default outbound: allow all

Stateful behavior:

If an inbound request is allowed (e.g., HTTP on port 80), the response is automatically allowed outbound—no explicit outbound rule needed.

Similarly, if an outbound request is allowed, the response is allowed inbound.

Security Group Evaluation

Rules are evaluated per-packet. If no rule allows traffic, it’s denied (default deny). Multiple security groups can attach to one instance—rules combine as union.

Instance Lifecycle

An EC2 instance moves through states:

| State | Compute Billing | Storage |

|---|---|---|

| pending | No | — |

| running | Yes | Attached |

| stopped | No | Persists |

| terminated | No | Deleted* |

*Root volume deleted by default; can configure to retain.

Stop preserves the instance. EBS volumes remain, private IP preserved. Restart later—may land on different physical host.

Terminate destroys the instance permanently. Cannot recover.

EBS: Persistent Block Storage

EBS (Elastic Block Store) provides persistent storage for EC2 instances.

Characteristics:

- Network-attached (not local disk)

- Persists independently of instance lifecycle

- Can detach and reattach to different instances

- Replicated within AZ for durability

Volume types:

| Type | Performance | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| gp3 | Balanced SSD | General purpose |

| io2 | High IOPS SSD | Databases |

| st1 | Throughput HDD | Big data |

| sc1 | Cold HDD | Infrequent access |

The AZ constraint:

EBS volumes exist in a specific Availability Zone. They can only attach to instances in the same AZ.

Volume in us-east-1a → Instance must be in us-east-1a

This is a consequence of the physical architecture: the volume’s data is stored on drives in that AZ’s datacenter.

Snapshots:

Point-in-time backup stored in S3 (regionally). Can create new volumes from snapshots in any AZ within the region.

EBS and Instance Relationship

By default, root volumes are deleted on termination. Additional volumes persist unless explicitly deleted. This allows data to survive instance replacement.

Connecting to Instances

To reach an EC2 instance:

Network path must exist:

- Instance has public IP (or you’re within the VPC)

- Security group allows traffic on the port (22 for SSH)

- Network ACLs permit traffic (usually default-allow)

- Route tables direct traffic appropriately

Authentication must succeed:

- SSH: private key matching the instance’s key pair

- Instance metadata can provide temporary credentials for AWS API access

The username depends on the AMI: ec2-user (Amazon Linux), ubuntu (Ubuntu), Administrator (Windows).

Instance Metadata Service

Every EC2 instance can query information about itself:

This link-local address is routed to the instance metadata service, accessible only from within the instance.

Available information:

| Path | Returns |

|---|---|

/instance-id |

i-0123456789abcdef0 |

/instance-type |

t3.micro |

/ami-id |

ami-0abcdef1234567890 |

/local-ipv4 |

172.31.16.42 |

/public-ipv4 |

54.xxx.xxx.xxx |

/placement/availability-zone |

us-east-1a |

/iam/security-credentials/{role} |

Temporary credentials JSON |

The SDKs use this endpoint to automatically obtain IAM role credentials when running on EC2—no access keys needed in code.

Identity and Access Management

EC2 Needs to Call AWS APIs

An EC2 instance runs your code. That code needs to access other AWS services:

- Read training data from S3

- Write results to S3

- Send messages to SQS

- Query DynamoDB

Each of these is an API call. S3 doesn’t know your EC2 instance—it receives an HTTPS request and must decide: should I allow this?

The request arrives at S3:

S3 must determine:

- Who is making this request?

- Are they allowed to write to this bucket?

Without proof of identity and permission, S3 rejects the request.

This is what IAM provides.

Two Questions Every API Call Must Answer

Authentication: Who is making this request?

- Requests are signed with credentials

- AWS verifies the signature matches a known identity

- Identity is a principal: user, role, or service

Authorization: Is this principal allowed to perform this action?

- Permissions defined in policies

- Policy specifies: this principal can do these actions on these resources

- AWS evaluates policies and returns allow or deny

Every AWS API call—from any source—goes through this evaluation. No exceptions.

Principals: Who Can Make Requests

Principal Identifiers: ARNs

Every AWS resource and principal has an Amazon Resource Name (ARN):

| Component | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Partition | aws |

Usually aws; aws-cn for China |

| Service | iam, s3, ec2 |

The AWS service |

| Region | us-east-1 |

Empty for global services (IAM) |

| Account | 123456789012 |

12-digit AWS account ID |

| Resource | user/alice, role/MyRole |

Service-specific format |

Examples:

arn:aws:iam::123456789012:user/alice

arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/EC2-S3-Reader

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/data/*

arn:aws:ec2:us-east-1:123456789012:instance/i-0abc123ARNs uniquely identify resources across all of AWS. Policies reference ARNs to specify who can do what to which resources.

Resource Identifiers

AWS generates unique identifiers for resources. The prefix indicates the resource type.

AWS-Generated IDs

| Prefix | Resource Type |

|---|---|

i- |

EC2 instance |

vol- |

EBS volume |

sg- |

Security group |

vpc- |

VPC |

subnet- |

Subnet |

ami- |

Machine image |

snap- |

EBS snapshot |

Example: i-0abcd1234efgh5678

These IDs are immutable—an instance keeps its ID through stop/start cycles. They’re region-scoped (except AMIs, which are region-specific but can be copied).

User-Defined Names

Some resources have user-chosen names:

- S3 buckets: globally unique (

my-company-data-2025) - IAM users/roles: account-scoped (

EC2-S3-Reader) - Tags: key-value metadata on any resource

Tags don’t affect behavior—they’re for organization, billing attribution, and automation (e.g., “terminate all instances tagged Environment=dev”).

Credentials: Proving Identity

API requests must be signed with credentials. AWS verifies the signature to authenticate the caller.

Long-term credentials:

- Access Key ID + Secret Access Key

- Created for IAM users

- Valid until explicitly revoked

- Stored in

~/.aws/credentialsor environment variables

# ~/.aws/credentials

[default]

aws_access_key_id = AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE

aws_secret_access_key = wJalrXUtnFE...Risk: If leaked, attacker has indefinite access until you notice and revoke.

Short-term credentials:

- Access Key ID + Secret Access Key + Session Token

- Obtained from STS (Security Token Service)

- Expire automatically (15 minutes to 12 hours)

- Cannot be revoked individually—just wait for expiration

{

"AccessKeyId": "ASIAXXX...",

"SecretAccessKey": "xxx...",

"SessionToken": "FwoGZX...",

"Expiration": "2025-01-28T14:30:00Z"

}Benefit: Limited blast radius. Leaked credentials expire.

How Credentials Become Requests

The SDK handles signing. You provide credentials (or it finds them automatically); it constructs the Authorization header. AWS verifies the signature by recomputing it with the same secret key.

Policies: The Permission Language

Permissions are defined in policy documents—JSON that specifies what’s allowed or denied.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/*"

}

]

}| Field | Purpose | Values |

|---|---|---|

Version |

Policy language version | Always "2012-10-17" |

Statement |

Array of permission rules | One or more statements |

Effect |

Allow or deny | "Allow" or "Deny" |

Action |

API operations | "s3:GetObject", "ec2:*", etc. |

Resource |

What the action applies to | ARN or ARN pattern |

Policy Statements in Detail

Actions are service:operation:

s3:GetObject # Read object

s3:PutObject # Write object

s3:DeleteObject # Delete object

s3:ListBucket # List bucket contents

s3:* # All S3 actions

ec2:RunInstances # Launch instance

ec2:TerminateInstances

ec2:Describe* # All Describe actionsWildcards match patterns:

s3:*— all S3 actionsec2:Describe*— all Describe actions*— all actions (dangerous)

Resources are ARNs or patterns:

# Specific object

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/data/file.json

# All objects in bucket

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/*

# All objects in prefix

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/data/*

# All buckets (rarely appropriate)

arn:aws:s3:::*

# All resources (dangerous)

*The bucket itself vs objects in it:

s3:ListBucket applies to the bucket. s3:GetObject applies to objects.

Multiple Statements

A policy can contain multiple statements. Common pattern: different permissions for different resources.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "ListBucket",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket"

},

{

"Sid": "ReadWriteObjects",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": ["s3:GetObject", "s3:PutObject"],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/*"

}

]

}Sid (statement ID) is optional—useful for documentation and debugging.

Both statements must be present: listing requires permission on the bucket, reading/writing requires permission on objects.

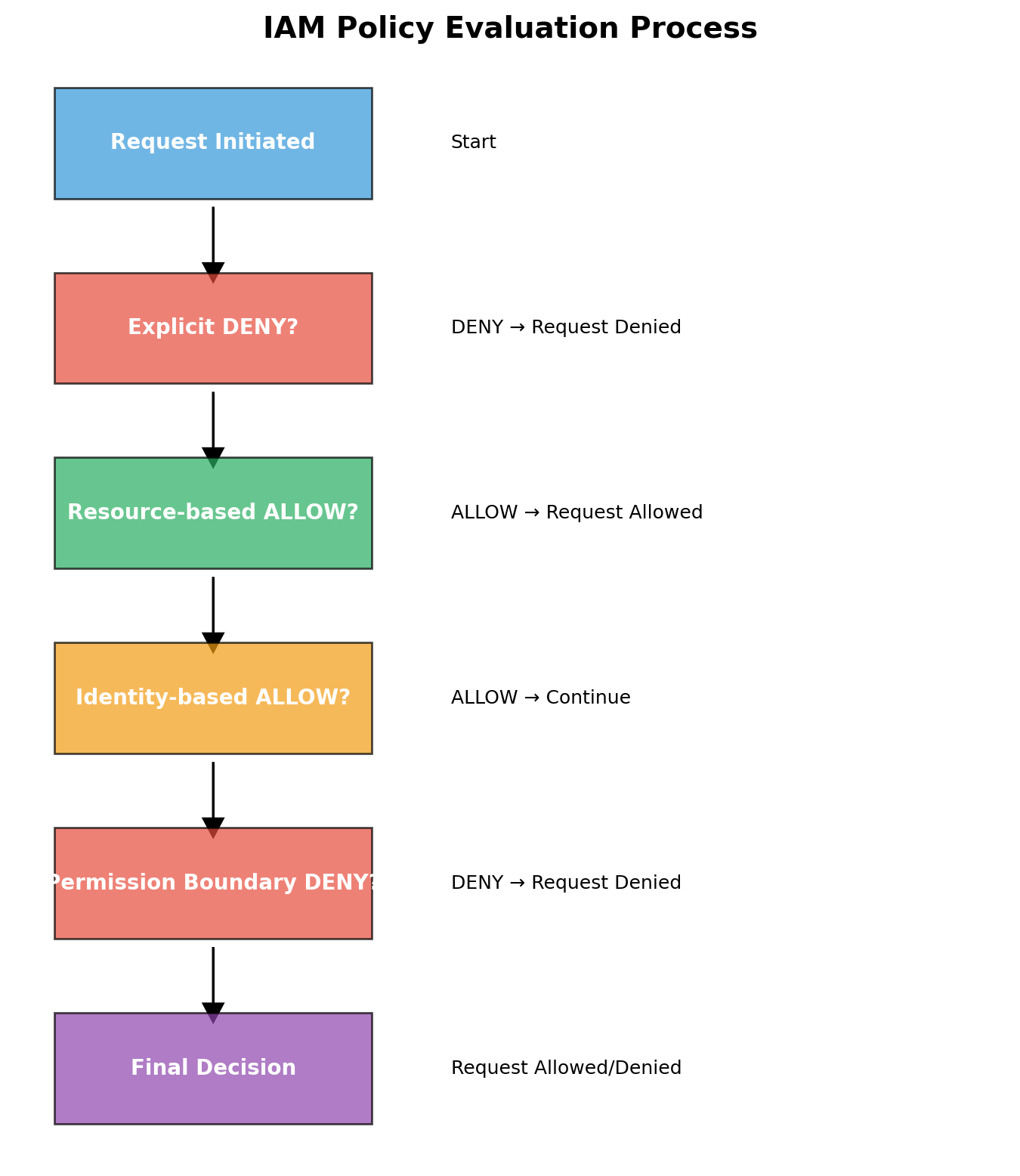

Policy Evaluation Logic

When a request arrives, AWS evaluates all applicable policies:

Evaluation Rules

| Rule | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Default deny | If no policy mentions the action, it’s denied |

| Explicit deny wins | A "Deny" statement overrides any "Allow" |

| Explicit allow grants | An "Allow" statement permits the action (unless denied) |

Practical implications:

- You must explicitly grant permissions—nothing is allowed by default

- You can’t “un-deny” something—deny is final

- Least privilege: start with nothing, add what’s needed

{

"Statement": [

{"Effect": "Allow", "Action": "s3:*", "Resource": "*"},

{"Effect": "Deny", "Action": "s3:DeleteBucket", "Resource": "*"}

]

}This allows all S3 actions except DeleteBucket. The deny wins.

Where Policies Attach

Identity-based: “This user/role can do X to Y”

Resource-based: “This resource allows X from Y” (includes Principal field)

Both are evaluated. For same-account access, either can grant. We focus on identity-based policies—they’re more common.

The Problem with Access Keys

Back to EC2 accessing S3. One approach: create an IAM user, generate access keys, put them in your code.

import boto3

s3 = boto3.client(

's3',

aws_access_key_id='AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE',

aws_secret_access_key='wJalrXUtnFEMI/K7MDENG/bPxRfiCYEXAMPLEKEY'

)

s3.get_object(Bucket='my-bucket', Key='data.json')Problems:

| Issue | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Keys in code | Checked into git, visible in repository |

| Keys on disk | Anyone with instance access can read them |

| Keys don’t expire | Leaked key = indefinite access |

| Keys per application | Managing many keys is error-prone |

| Key rotation | Manual process, often neglected |

This is how credentials get leaked. Public GitHub repositories are scanned constantly for AWS keys.

IAM Roles: Identity Without Permanent Credentials

A role is an IAM identity that:

- Has permissions (via attached policies)

- Has no permanent credentials

- Can be assumed by trusted entities

- Issues temporary credentials when assumed

Assuming a Role

When an entity assumes a role, AWS STS (Security Token Service) issues temporary credentials:

Credentials expire (default 1 hour, configurable). When they expire, assume the role again to get new ones.

Instance Profiles: Roles for EC2

EC2 instances assume roles through instance profiles.

Instance profile = container that holds an IAM role

When you launch an instance with an instance profile:

- EC2 service assumes the role on the instance’s behalf

- Temporary credentials are made available inside the instance

- Credentials are served at the metadata endpoint

http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/MyRoleResponse:

Instance Profile Architecture

- boto3 queries metadata service for credentials

- Metadata service obtains temporary credentials from STS using instance profile’s role

- boto3 signs request to S3 with those credentials

The Credential Chain

SDKs search for credentials in a defined order:

On EC2 with an instance profile, the SDK automatically uses instance metadata. No configuration needed.

Complete Example: EC2 Reading S3

1. Create IAM Role with trust policy:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {"Service": "ec2.amazonaws.com"},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole"

}]

}2. Attach permissions policy to role:

Complete Example (continued)

3. Create instance profile and attach role:

aws iam create-instance-profile --instance-profile-name EC2-S3-Reader

aws iam add-role-to-instance-profile \

--instance-profile-name EC2-S3-Reader \

--role-name EC2-S3-Reader-Role4. Launch EC2 with instance profile:

aws ec2 run-instances \

--image-id ami-0c55b159cbfafe1f0 \

--instance-type t3.micro \

--iam-instance-profile Name=EC2-S3-Reader \

--key-name my-key5. Code on the instance:

Why This Matters

| With access keys | With IAM roles |

|---|---|

| Keys in code or config files | No keys to leak |

| Keys valid indefinitely | Credentials expire automatically |

| Manual rotation required | Automatic rotation |

| Keys can be copied anywhere | Credentials tied to instance |

| Compromised key = long-term access | Compromised instance = temporary access |

Instance compromise is still serious—attacker gets whatever permissions the role has. But they don’t get permanent credentials they can use after losing access to the instance.

Least privilege: give roles only the permissions they need. s3:GetObject on one bucket, not s3:* on *.

Storage: S3

Object Storage

EBS provides block storage—raw disk that an OS formats and manages as a filesystem. S3 provides object storage—a different abstraction entirely.

Block storage (EBS):

- Raw blocks, OS manages filesystem

- Attached to one instance

- POSIX semantics: open, read, write, seek, close

- Directories, permissions, links

- Mutable: change byte 1000 without touching rest

The filesystem abstraction you already know.

Object storage (S3):

- Key-value store over HTTP

- Accessible from anywhere

- HTTP semantics: PUT, GET, DELETE

- No directories, no permissions bits

- Immutable: replace entire object or nothing

A different model optimized for different access patterns.

S3 is not a filesystem you mount. It’s a service you call.

The S3 Data Model

S3 organizes data into buckets containing objects.

Bucket: a container with a globally unique name

training-data-2025— yours, no one else can use this name- Exists in one region (data stored there)

- Holds any number of objects

Object: a key-value pair

- Key: a string identifying the object (

models/v1/weights.pt) - Value: bytes (the actual data, up to 5 TB)

- Metadata: key-value pairs describing the object

That’s it. Buckets hold objects. Objects are key + bytes + metadata.

Keys Are Strings, Not Paths

The “/” Is Just a Character

The AWS Console and CLI show a folder-like view. This is a UI convenience, not reality.

# These are three separate objects with no relationship:

data/train/batch-001.csv

data/train/batch-002.csv

data/test/batch-001.csv

# There is no "data" directory

# There is no "data/train" directory

# You cannot "cd" into anything

# You cannot "ls" a directory (you filter by prefix)What “listing a directory” actually does:

This calls ListObjectsV2 with Prefix="data/train/" and Delimiter="/". S3 returns objects whose keys start with that prefix. The slash delimiter groups results to simulate folders.

No directory was traversed. A string filter was applied.

Why This Matters

The flat namespace has consequences:

No “rename” operation

Renaming old-name.csv to new-name.csv requires:

- Copy object to new key

- Delete object at old key

For a 5 GB file, this means uploading 5 GB again (within S3, but still a copy).

Filesystems rename by changing a pointer. S3 doesn’t have pointers.

No “move” operation

Same as rename—copy then delete.

No “append” operation

Adding 100 bytes to a 5 GB file requires:

- Download 5 GB

- Append 100 bytes locally

- Upload 5.000000095 GB

Or: store as separate objects and concatenate at read time.

Filesystems append by extending allocation. S3 objects are immutable blobs.

No partial update

Changing byte 1000 requires replacing the entire object.

Objects Are Immutable

Once written, an object cannot be modified—only replaced entirely.

# This doesn't append—it overwrites

s3.put_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='log.txt',

Body='new content' # Replaces everything

)Design implications:

- Logs: write each entry as separate object, or batch and write periodically

- Large datasets: partition into multiple objects

- Results: write once when complete, not incrementally

This isn’t a limitation to work around—it’s a model to design for. Many distributed systems work well with immutable data.

HTTP Operations

S3 is an HTTP API. Every operation is an HTTP request.

| Operation | HTTP Method | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

PutObject |

PUT | Create/replace object |

GetObject |

GET | Retrieve object (or byte range) |

DeleteObject |

DELETE | Remove object |

HeadObject |

HEAD | Get metadata without body |

ListObjectsV2 |

GET on bucket | List keys matching prefix |

PUT /my-bucket/data/file.csv HTTP/1.1

Host: s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Content-Length: 1048576

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 ...

<file bytes>The CLI and SDK construct these requests. Understanding that it’s HTTP explains the operation set—HTTP doesn’t have “append” or “rename” either.

Working with S3: CLI

# Create bucket (name must be globally unique)

aws s3 mb s3://my-bucket-unique-name-12345

# Upload file

aws s3 cp ./local-file.csv s3://my-bucket/data/file.csv

# Download file

aws s3 cp s3://my-bucket/data/file.csv ./local-file.csv

# List objects (with prefix filter, not directory listing)

aws s3 ls s3://my-bucket/data/

# Sync local directory to S3 (uploads new/changed files)

aws s3 sync ./local-dir/ s3://my-bucket/data/

# Delete object

aws s3 rm s3://my-bucket/data/file.csv

# Delete all objects with prefix

aws s3 rm s3://my-bucket/data/ --recursiveaws s3 commands are high-level conveniences. aws s3api exposes the raw API operations.

Working with S3: SDK

import boto3

import json

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# Upload object

s3.put_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='results/experiment-001.json',

Body=json.dumps({'accuracy': 0.94, 'loss': 0.23}),

ContentType='application/json'

)

# Download object

response = s3.get_object(Bucket='my-bucket', Key='results/experiment-001.json')

data = json.loads(response['Body'].read())

# List objects with prefix

response = s3.list_objects_v2(Bucket='my-bucket', Prefix='results/')

for obj in response.get('Contents', []):

print(f"{obj['Key']}: {obj['Size']} bytes")S3 from EC2: The IAM Pattern

EC2 instance needs to read from S3. This is the IAM role pattern from Part 3.

Role trust policy (who can assume):

{

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {"Service": "ec2.amazonaws.com"},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole"

}]

}Role permissions policy (what they can do):

{

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": ["s3:GetObject", "s3:PutObject"],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::training-data-bucket/*"

}]

}Instance launched with this role’s instance profile. Code on instance:

Bucket ARN vs Object ARN

A common permissions mistake: policy grants object access but not bucket access.

This allows downloading objects. But listing what’s in the bucket:

ListBucket is a bucket operation, not an object operation. It needs the bucket ARN:

{

"Statement": [

{

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket"

},

{

"Action": ["s3:GetObject", "s3:PutObject"],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/*"

}

]

}Note: my-bucket (the bucket) vs my-bucket/* (objects in the bucket).

ARN Structure for S3

S3 ARNs don’t include region or account for buckets (bucket names are globally unique):

arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name # The bucket itself

arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name/* # All objects in bucket

arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name/prefix/* # Objects under prefix

arn:aws:s3:::bucket-name/exact-key # Specific object| ARN | Applies To |

|---|---|

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket |

ListBucket, GetBucketLocation, bucket operations |

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/* |

GetObject, PutObject, DeleteObject, object operations |

arn:aws:s3:::my-bucket/data/* |

Object operations on keys starting with data/ |

Getting this wrong is the most common S3 permissions error.

Durability and Availability

Two different guarantees:

Durability: probability data survives

S3 Standard: 99.999999999% (11 nines)

S3 stores copies across multiple facilities in the region. Designed to sustain simultaneous loss of two facilities.

10 million objects → expect to lose 1 every 10,000 years.

If you PUT successfully, the data is safe.

Availability: probability you can access it

S3 Standard: 99.99%

About 53 minutes/year of potential unavailability.

Availability failures are transient—retry and it works. Data isn’t lost, just temporarily unreachable.

GET might fail occasionally; data is still there.

High durability doesn’t guarantee high availability. They’re independent properties.

S3 in Application Architecture

S3 serves as durable storage accessible from any compute resource:

Training runs, writes model to S3, terminates. Serving instances start, read model from S3. Lambda processes uploads. All access the same data. S3 persists regardless of which compute resources exist.

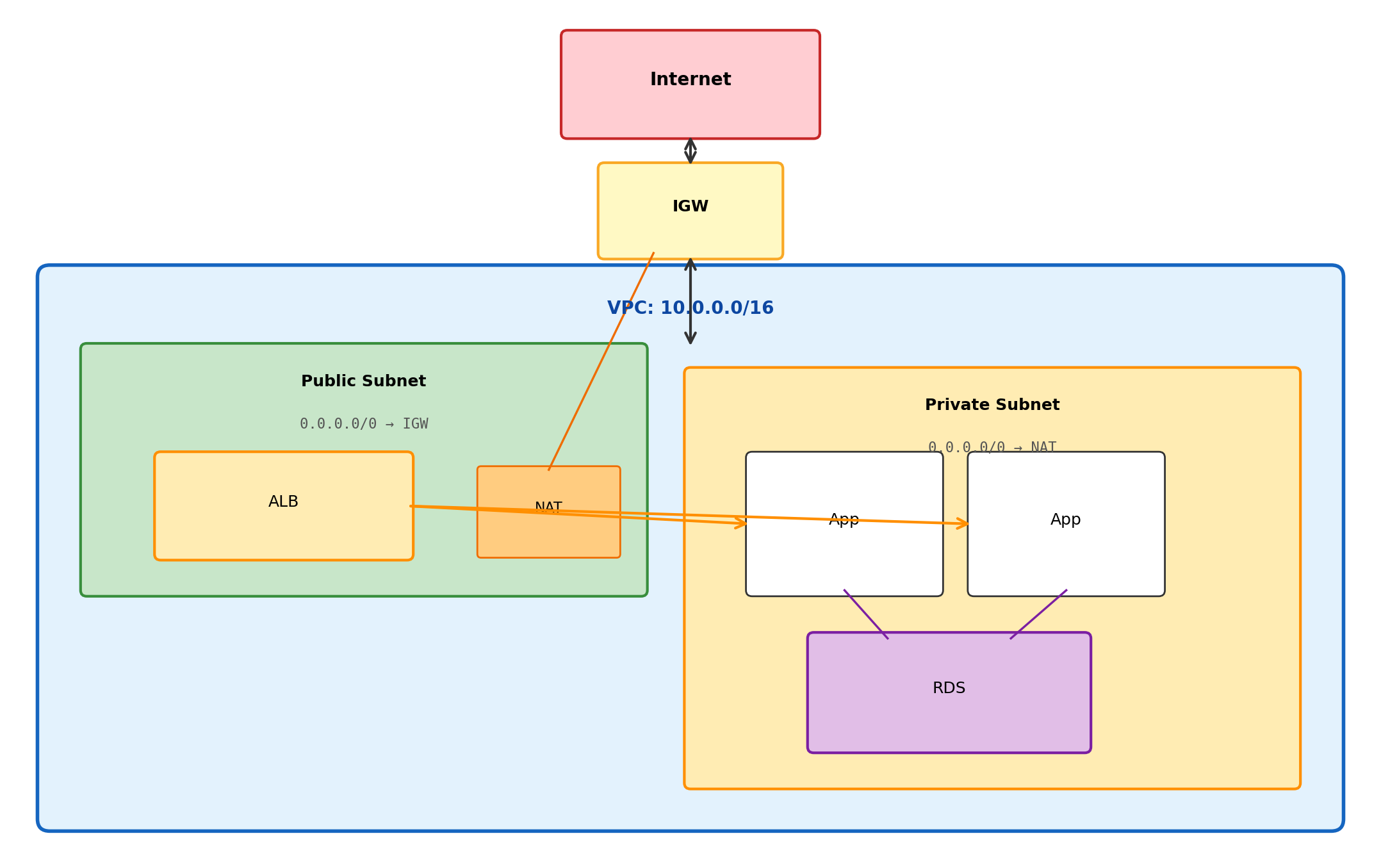

Networking

Where Instances Live

When you launch an EC2 instance, it needs a network. IP address, routing, connectivity to other instances and the internet.

AWS doesn’t put your instance on a shared public network. It goes into a VPC—a Virtual Private Cloud that belongs to your account.

VPC properties:

- Isolated network within AWS

- You define the IP address range

- Spans all AZs in a region

- Your instances, your network, your rules

Other AWS accounts can’t see into your VPC. Traffic between VPCs is isolated by default.

Default VPC:

Every region has a default VPC created automatically. When you launch an instance without specifying networking, it goes here.

For learning and simple deployments, the default VPC works fine. Production environments typically use custom VPCs with deliberate network design.

We’ll use the default VPC.

IP Address Ranges

A VPC has a CIDR block—the range of private IP addresses available within it.

10.0.0.0/16This notation specifies a range:

10.0.0.0— starting address/16— first 16 bits are fixed, remaining 16 bits vary

10.0.0.0/16 includes 10.0.0.0 through 10.0.255.255 — 65,536 addresses.

| CIDR | Range | Addresses |

|---|---|---|

10.0.0.0/16 |

10.0.0.0 – 10.0.255.255 | 65,536 |

10.0.0.0/24 |

10.0.0.0 – 10.0.0.255 | 256 |

10.0.1.0/24 |

10.0.1.0 – 10.0.1.255 | 256 |

These are private IP addresses—not routable on the public internet. Within your VPC, instances use these addresses to communicate.

To reach the internet, instances need either:

- A public IP (mapped to private IP)

- NAT (translates private to public)

Subnets Partition the VPC

A VPC spans an entire region. Subnets divide it into segments, each in a specific AZ.

Subnet Properties

Each subnet:

| Property | Implication |

|---|---|

| Exists in one AZ | Instances in this subnet run in this AZ |

| Has a CIDR block | Subset of VPC’s range (e.g., 10.0.1.0/24 within 10.0.0.0/16) |

| Has a route table | Determines where traffic goes |

| Is public or private | Based on routing, not a flag |

The AZ constraint revisited:

When you launch an EC2 instance, you specify a subnet. The subnet determines the AZ. This is why EBS volumes must match—the volume and instance must be in the same AZ, and subnet selection determines instance AZ.

Public vs Private Subnets

The terms “public” and “private” describe routing behavior, not a setting you toggle.

Public subnet:

Route table includes:

Destination Target

10.0.0.0/16 local

0.0.0.0/0 igw-xxx ← Internet GatewayTraffic to addresses outside the VPC routes to the Internet Gateway. Instances with public IPs can receive inbound traffic from the internet.

Private subnet:

Route table includes:

Destination Target

10.0.0.0/16 localNo route to internet. Traffic to external addresses has nowhere to go.

Instances here cannot be reached from the internet—no inbound path exists.

The subnet becomes “public” by having a route to an Internet Gateway. Remove that route, it becomes “private.”

Internet Gateway

An Internet Gateway (IGW) connects your VPC to the public internet.

IGW is horizontally scaled and highly available—AWS manages it. You attach one to your VPC; it handles the translation between public and private IPs.

Public IP Addresses

An instance in a public subnet still needs a public IP to be reachable from the internet.

Auto-assigned public IP:

- Assigned at launch from AWS’s pool

- Released when instance stops

- New IP on restart

- Free

Elastic IP:

- Static public IP you allocate

- Persists until you release it

- Can move between instances

- Small charge when not attached

Useful when you need a stable IP (DNS records, firewall whitelists).

The mapping:

Instance has private IP 10.0.1.5 and public IP 54.x.x.x. The IGW translates—outbound traffic appears from 54.x.x.x, inbound traffic to 54.x.x.x routes to 10.0.1.5.

Private Subnet Outbound Access

Instances in private subnets often need outbound internet access—downloading packages, calling external APIs—without being reachable from the internet.

NAT Gateway enables this:

Private subnet route table: 0.0.0.0/0 → nat-xxx. Outbound traffic goes to NAT Gateway (in public subnet), which forwards to IGW. Inbound from internet still has no path to private instances.

NAT Gateway Costs

NAT Gateway is a managed service with meaningful cost:

| Component | Price |

|---|---|

| Hourly charge | ~$0.045/hour (~$32/month) |

| Data processing | $0.045/GB |

A NAT Gateway running continuously with moderate traffic can cost $50-100/month. For development, consider:

- NAT Instance (EC2 instance doing NAT—cheaper, more management)

- Only create NAT Gateway when needed

- Use VPC Endpoints for AWS service traffic (avoids NAT)

Production typically uses NAT Gateway for reliability. Development often skips it or uses alternatives.

Traffic Flow: Internet to Instance

A request from the internet reaching an instance traverses multiple layers:

For traffic to reach an instance:

- Route must exist (public subnet with IGW route)

- Network ACL must allow (default allows all—we won’t modify these)

- Security group must allow (you configure this)

Security Groups in Network Context

Security groups control traffic at the instance level. Recap from EC2 section:

Inbound rules:

Type Port Source

────────────────────────────

SSH 22 0.0.0.0/0

HTTP 80 0.0.0.0/0

Custom 5432 10.0.0.0/16Each rule: allow traffic matching protocol, port, source.

Default: deny all inbound

Stateful behavior:

If inbound request is allowed, response is automatically allowed outbound.

An HTTP request allowed inbound on port 80 can respond without an explicit outbound rule for that connection.

Implication: You typically only configure inbound rules. Outbound defaults to allow-all, and stateful tracking handles responses.

Security groups apply regardless of subnet type. A public subnet instance still needs security group rules to accept traffic.

Security Group References

Security groups can reference other security groups, not just IP ranges:

“Allow traffic from instances in security group sg-loadbalancer” — even if their IPs change.

App servers accept HTTP only from load balancer, regardless of IP changes. Database accepts connections only from app servers.

VPC Endpoints

S3, DynamoDB, and other AWS services exist outside your VPC. By default, traffic goes over the public internet (through IGW or NAT).

VPC Endpoints provide private connectivity:

Gateway Endpoints (S3, DynamoDB):

- Route table entry directs traffic

- No NAT, no IGW for this traffic

- Free

- Traffic stays on AWS network

Destination Target

pl-xxx (S3 prefix) vpce-xxxInterface Endpoints (most other services):

- ENI in your subnet with private IP

- Service accessible at that IP

- Hourly charge + data processing

- Useful for private subnets accessing AWS APIs

For private subnets that need S3 access, a Gateway Endpoint avoids NAT Gateway costs and keeps traffic private.

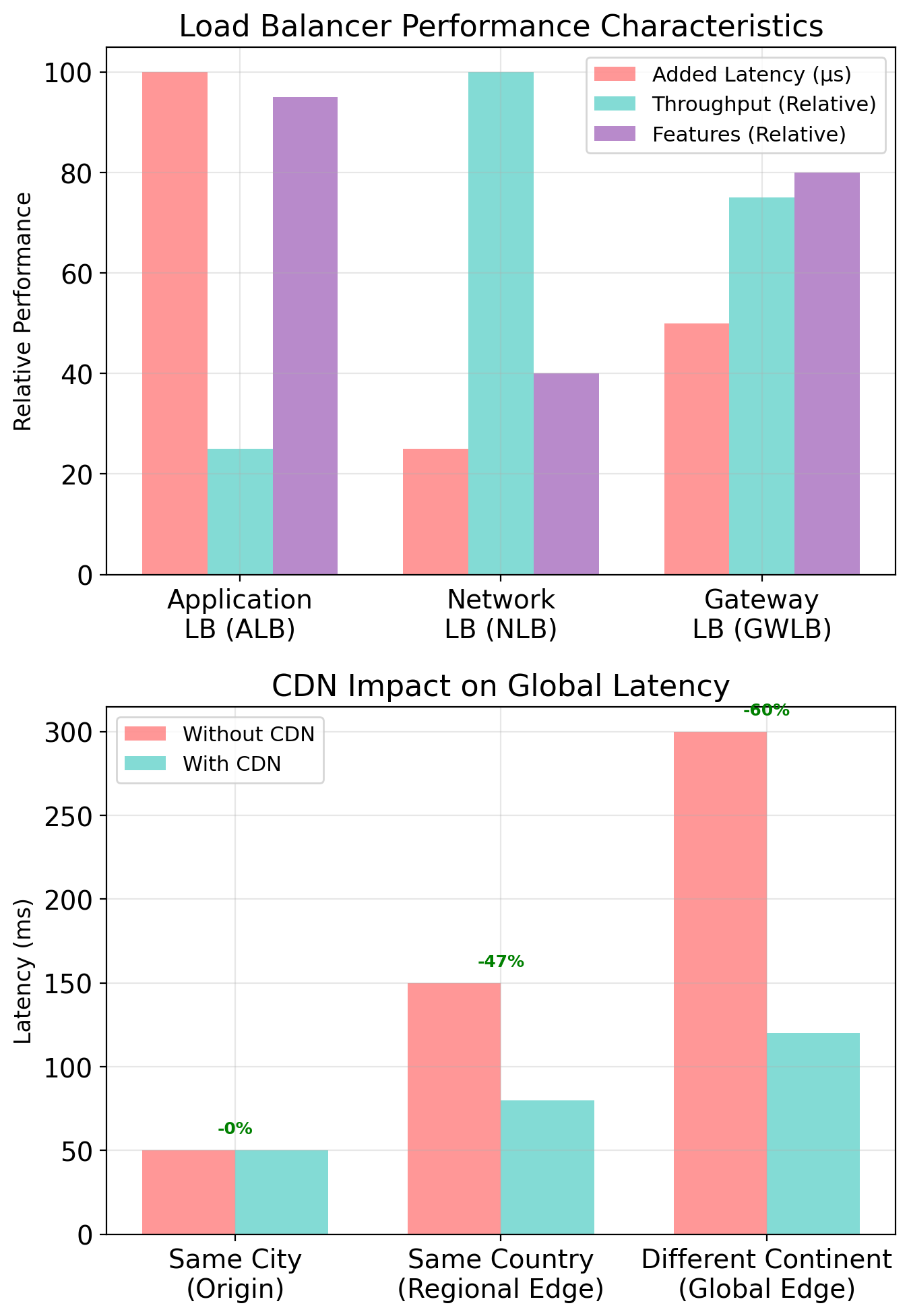

Load Balancing

Distributing traffic across multiple instances:

Application Load Balancer (ALB):

- Operates at HTTP layer (Layer 7)

- Routes based on path, host, headers

- Health checks instances

- Single DNS endpoint, multiple backends

Users hit one DNS name. ALB distributes requests. If an instance fails health checks, ALB stops sending it traffic. We’ll configure this in later assignments.

Public and Private Subnets Together

Public subnet — internet-facing components

- Load balancer (receives user traffic)

- NAT gateway (enables private outbound)

- Bastion host if needed (SSH jump box)

Private subnet — internal components

- Application servers (behind load balancer)

- Databases (no internet exposure)

- Outbound via NAT (updates, external APIs)

Networking in the AWS Model

VPC provides isolation—your network, your rules. Within it:

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| Subnets | Determine AZ placement and routing behavior |

| Route tables | Define public vs private (IGW route or not) |

| Security groups | Control traffic at instance level |

| NAT/Endpoints | Enable private subnet outbound access |

Networking is foundational. EC2 instances, RDS databases, Lambda functions (in VPC mode), and load balancers all exist within this structure. The choices made here—which subnets, which security groups, which routes—determine what can communicate with what.

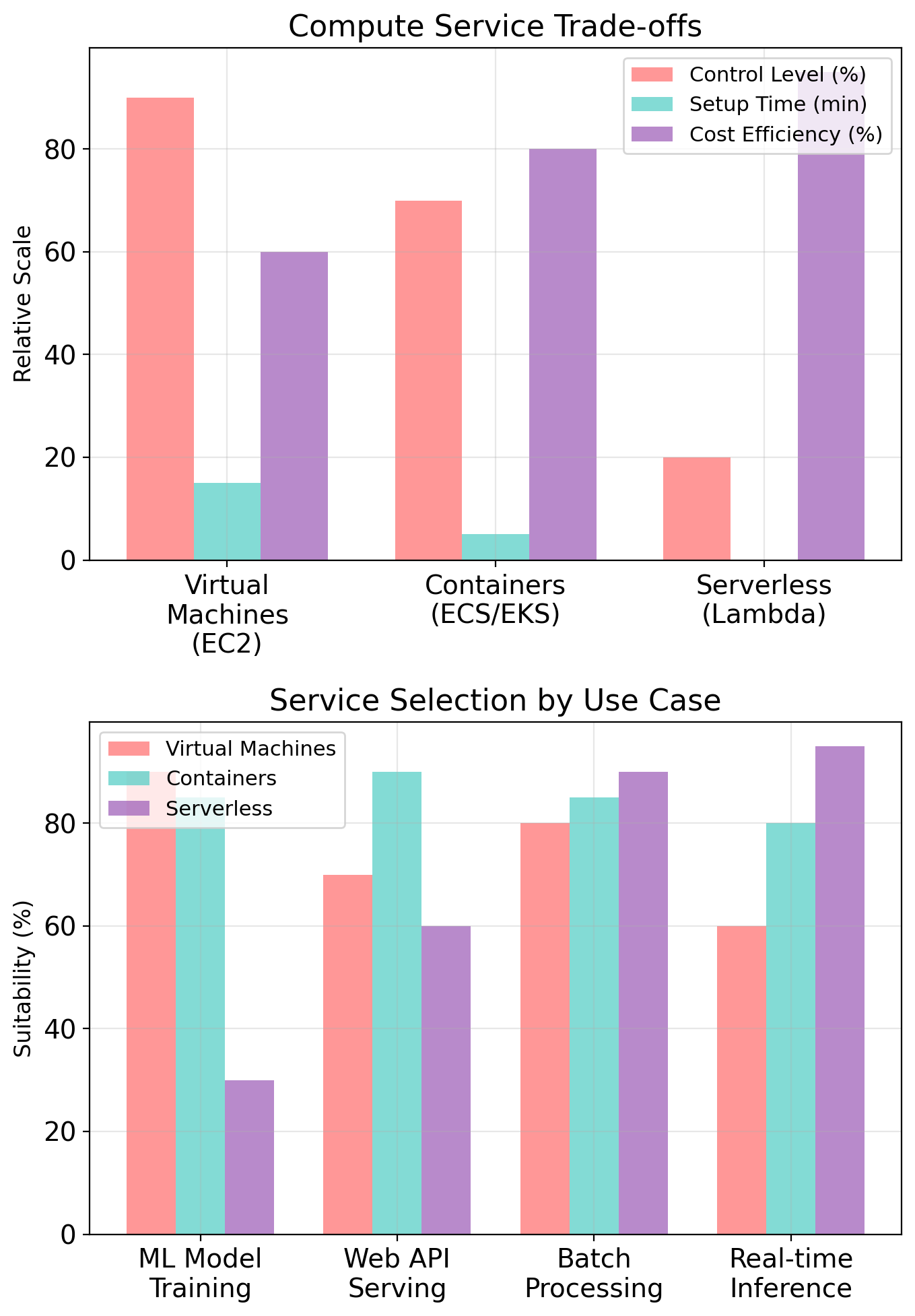

Service Survey

Beyond EC2 and S3

EC2 provides virtual machines. S3 provides object storage. These are foundational, but AWS offers other models for computation and data.

This section briefly introduces services you’ll encounter in assignments and later lectures:

| Service | What It Provides |

|---|---|

| Lambda | Run code without managing servers |

| SQS | Message queues |

| SNS | Notification delivery |

| RDS | Managed relational databases |

| DynamoDB | Managed NoSQL database |

We cover what each does and when you might use it. Deeper treatment comes in dedicated lectures on databases and application patterns.

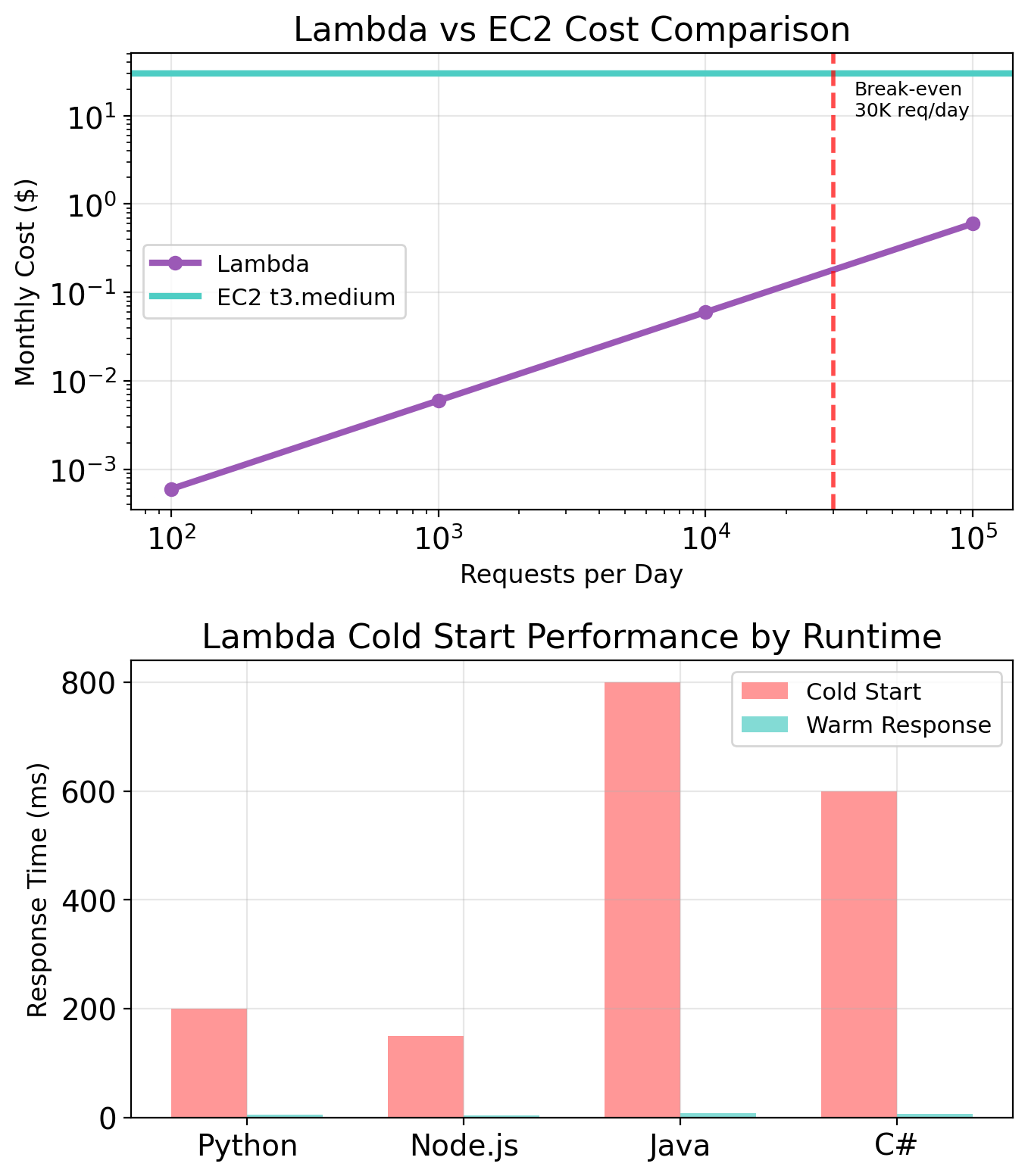

Lambda: Functions as a Service

EC2 requires you to provision instances, keep them running, and pay by the hour. Lambda offers a different model: upload code, AWS runs it when triggered.

How it works:

- You write a function (Python, Node.js, etc.)

- You upload it to Lambda

- Something triggers it (HTTP request, S3 upload, schedule)

- Lambda runs your function

- You pay for execution time

No instances to manage. No servers to patch. Code runs, then nothing exists until next trigger.

Lambda Triggers and Use Cases

Lambda functions respond to events from various sources:

| Trigger | Example Use |

|---|---|

| API Gateway | HTTP endpoint calls Lambda |

| S3 | Object uploaded → process it |

| Schedule | Run every hour (cron-like) |

| SQS | Message arrives → process it |

| DynamoDB | Record changes → react |

Common patterns:

- Resize images when uploaded to S3

- Process webhook callbacks

- Run periodic cleanup tasks

- Handle API requests without running a server

Lambda suits workloads that are event-driven, short-lived, and don’t need persistent state between invocations.

Lambda Constraints

Lambda trades flexibility for simplicity. Constraints to know:

| Constraint | Limit |

|---|---|

| Execution timeout | 15 minutes maximum |

| Memory | 128 MB to 10 GB |

| Deployment package | 250 MB (unzipped) |

| Concurrency | 1000 default (can request increase) |

| Stateless | No persistent local storage between invocations |

Cold starts: First invocation (or after idle period) takes longer—Lambda must initialize your code. Subsequent invocations reuse the warm environment. Latency-sensitive applications may notice this delay.

Lambda isn’t a replacement for EC2. It’s a different tool for different workload shapes. Long-running processes, persistent connections, or large memory requirements typically need EC2.

Lambda Pricing

Pay for what you execute:

| Component | Price |

|---|---|

| Requests | $0.20 per million |

| Duration | $0.0000166667 per GB-second |

A function using 512 MB running for 200ms:

- 0.5 GB × 0.2 seconds = 0.1 GB-seconds

- 0.1 × $0.0000166667 ≈ $0.0000017 per invocation

1 million invocations at this configuration ≈ $2.

Contrast with EC2: a t3.micro running continuously costs ~$7.50/month regardless of whether it’s doing work. Lambda costs nothing when idle.

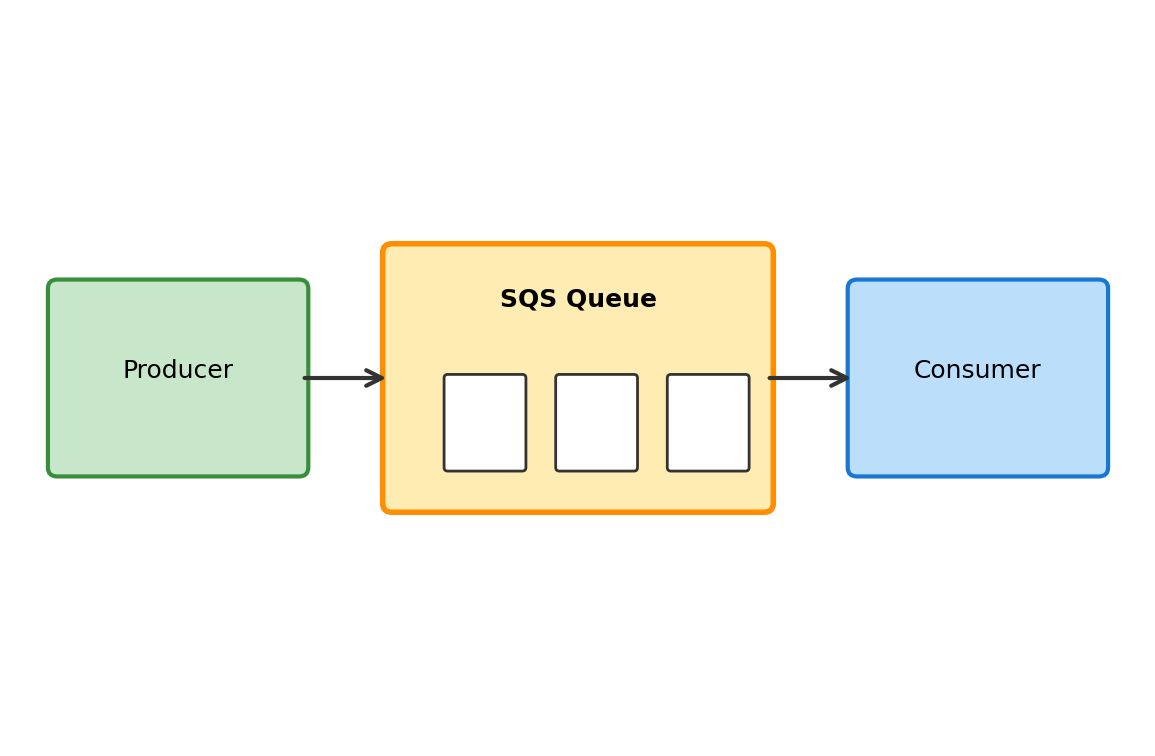

SQS: Message Queues

SQS (Simple Queue Service) provides message queues—a way for one component to send work to another without direct connection.

The concept:

A queue holds messages. One component (producer) puts messages in. Another component (consumer) takes messages out and processes them.

Producer and consumer don’t communicate directly. The queue sits between them.

# Producer: send message

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl='https://sqs.../my-queue',

MessageBody='{"task": "process", "id": 123}'

)

# Consumer: receive and process

messages = sqs.receive_message(QueueUrl='...')

for msg in messages.get('Messages', []):

process(msg['Body'])

sqs.delete_message(...) # Acknowledge

Why Queues Matter

Queues enable patterns we’ll study in depth later. For now, the key ideas:

Producer doesn’t wait for consumer

Send a message and continue. If the consumer is slow or temporarily unavailable, messages accumulate in the queue. No work is lost.

Consumer processes at its own pace

Consumer pulls messages when ready. If overwhelmed, messages wait. Can add more consumers to process faster.

Components are independent

Producer and consumer can be deployed, scaled, and updated separately. They agree on message format, not on being available simultaneously.

We’ll explore these patterns in the lecture on asynchronous communication. SQS is the AWS service that implements them.

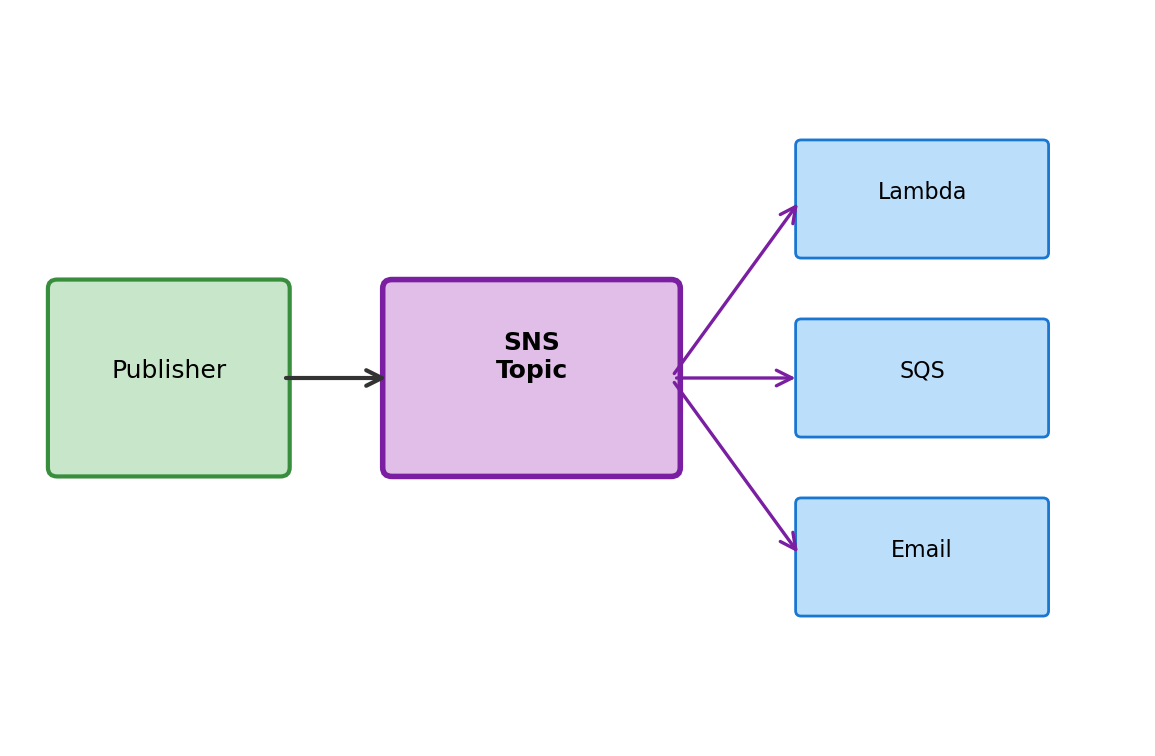

SNS: Notifications

SNS (Simple Notification Service) delivers messages to subscribers—one message, potentially many recipients.

The concept:

A topic is a channel. Publishers send messages to topics. Subscribers receive messages from topics they’re subscribed to.

One publish → many deliveries.

Subscriber types:

- Lambda functions

- SQS queues

- HTTP endpoints

- Email addresses

- SMS

Example: Order placed → publish to “orders” topic → triggers: inventory Lambda, send email confirmation, queue for shipping system. One event, multiple reactions.

SQS vs SNS

| SQS | SNS | |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Queue (one consumer per message) | Pub/sub (many subscribers per message) |

| Delivery | Consumer pulls | SNS pushes to subscribers |

| Persistence | Messages wait in queue | Delivery attempted immediately |

| Use case | Work distribution | Event notification |

Often used together: SNS publishes to multiple SQS queues, each processed by different consumer applications.

RDS: Managed Relational Databases

Applications often need to store structured data—users, orders, inventory—with relationships between records. Relational databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL) provide this.

Running a database yourself requires:

- Installing and configuring the software

- Managing storage and backups

- Applying security patches

- Setting up replication for reliability

- Monitoring performance

RDS (Relational Database Service) handles this operational work. You get a database endpoint; AWS manages the infrastructure.

RDS Characteristics

What you choose:

- Database engine (PostgreSQL, MySQL, MariaDB, Oracle, SQL Server)

- Instance size (CPU, memory)

- Storage type and size

- Multi-AZ (automatic failover replica)

What AWS manages:

- Backups (automated, point-in-time recovery)

- Patches (maintenance windows)

- Monitoring (CloudWatch metrics)

- Failover (if Multi-AZ enabled)

What you get:

An endpoint:

mydb.abc123.us-east-1.rds.amazonaws.com:5432Connect with standard database tools and libraries:

import psycopg2

conn = psycopg2.connect(

host='mydb.abc123.us-east-1.rds.amazonaws.com',

database='myapp',

user='admin',

password='...'

)From your application’s perspective, it’s a PostgreSQL database. The managed part is invisible.

DynamoDB: Managed NoSQL

DynamoDB is a different kind of database—NoSQL, specifically key-value and document storage.

Different model from relational:

- No fixed schema—each item can have different attributes

- Access by primary key (fast) or scan (slow)

- No joins—denormalized data

- Scales horizontally

Serverless pricing model:

Pay per request or provision capacity. No instance to size—scales automatically.

import boto3

dynamodb = boto3.resource('dynamodb')

table = dynamodb.Table('Users')

# Write item

table.put_item(Item={

'user_id': 'u123',

'name': 'Alice',

'email': 'alice@example.com'

})

# Read item by key

response = table.get_item(Key={'user_id': 'u123'})

user = response['Item']Access patterns are different from SQL. We’ll cover when each model fits in the database lectures.

RDS vs DynamoDB

| RDS | DynamoDB | |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Relational (SQL) | Key-value / document (NoSQL) |

| Schema | Fixed, defined upfront | Flexible, per-item |

| Queries | SQL, joins, complex queries | Key lookup, limited queries |

| Scaling | Vertical (bigger instance) | Horizontal (automatic) |

| Pricing | Instance hours | Request-based or provisioned |

| Managed | Partially (you choose instance) | Fully (no servers to size) |

Neither is better—they fit different problems. Applications often use both: RDS for relational data with complex queries, DynamoDB for high-scale key-value access.

We’ll study these tradeoffs in the database lectures.

Costs

Resource Metering

AWS bills based on resource usage. Different resources meter in fundamentally different ways:

| Metering Model | How It Works | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Time-based | Charge per unit time resource exists/runs | EC2 instances, RDS instances, NAT Gateway |

| Capacity-based | Charge per unit capacity provisioned | EBS volumes, provisioned IOPS |

| Usage-based | Charge per unit actually consumed | S3 storage, S3 requests, Lambda invocations |

| Movement-based | Charge per unit data transferred | Data transfer out, cross-region transfer |

A single deployment involves multiple metering models simultaneously. An EC2 instance incurs time-based charges (compute), capacity-based charges (EBS), and potentially movement-based charges (data transfer).

Understanding the metering model lets you reason about costs before incurring them.

EC2 Costs

EC2 instances charge per-second while in the running state (60-second minimum).

| Instance Type | Hourly | Monthly (continuous) |

|---|---|---|

| t3.micro | $0.0104 | $7.59 |

| t3.small | $0.0208 | $15.18 |

| t3.medium | $0.0416 | $30.37 |

| m5.large | $0.096 | $70.08 |

| m5.xlarge | $0.192 | $140.16 |

On-Demand pricing, us-east-1, Linux. Other regions ±10-20%.

Instance state determines billing:

| State | Compute Charge | EBS Charge |

|---|---|---|

| running | Yes | Yes |

| stopped | No | Yes |

| terminated | No | No (volume deleted) |

Stopping an instance stops compute charges. The EBS volume still exists and still bills. Terminating ends all charges (root volume deleted by default).

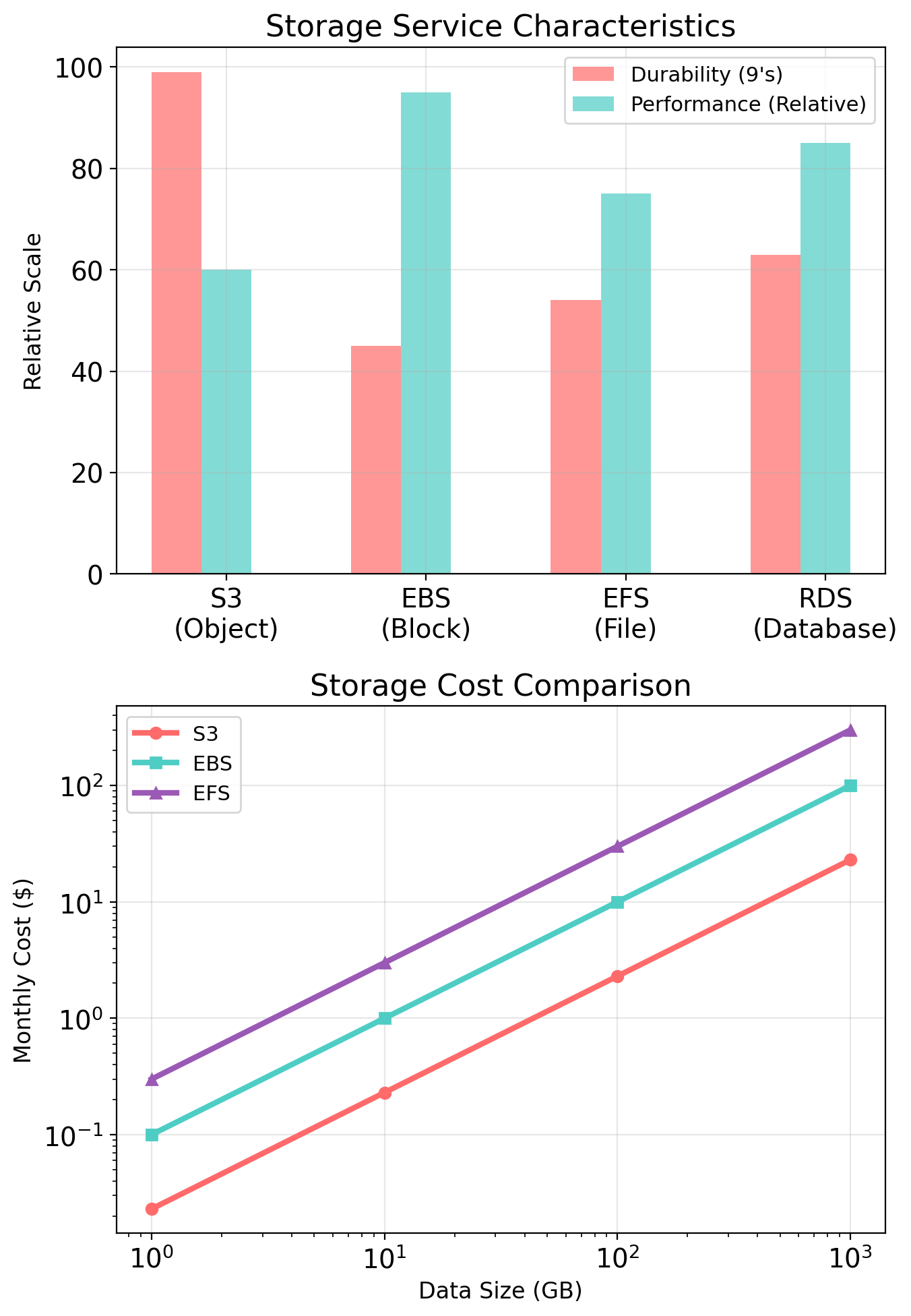

Storage Costs

EBS and S3 use different metering models:

EBS: Capacity-based

Charges for provisioned size, not used space.

| Volume Type | Per GB-month |

|---|---|

| gp3 | $0.08 |

| gp2 | $0.10 |

| io2 | $0.125 + IOPS |

A 100 GB gp3 volume: $8/month

Whether you store 1 GB or 100 GB on it, the charge is the same. You’re paying for the capacity you reserved.

S3: Usage-based

Charges for actual storage plus operations.

| Component | Price |

|---|---|

| Storage (Standard) | $0.023/GB-month |

| PUT/POST/LIST | $0.005/1,000 |

| GET/SELECT | $0.0004/1,000 |

100 GB stored: $2.30/month

S3 charges grow with actual data stored. Empty bucket costs nothing.

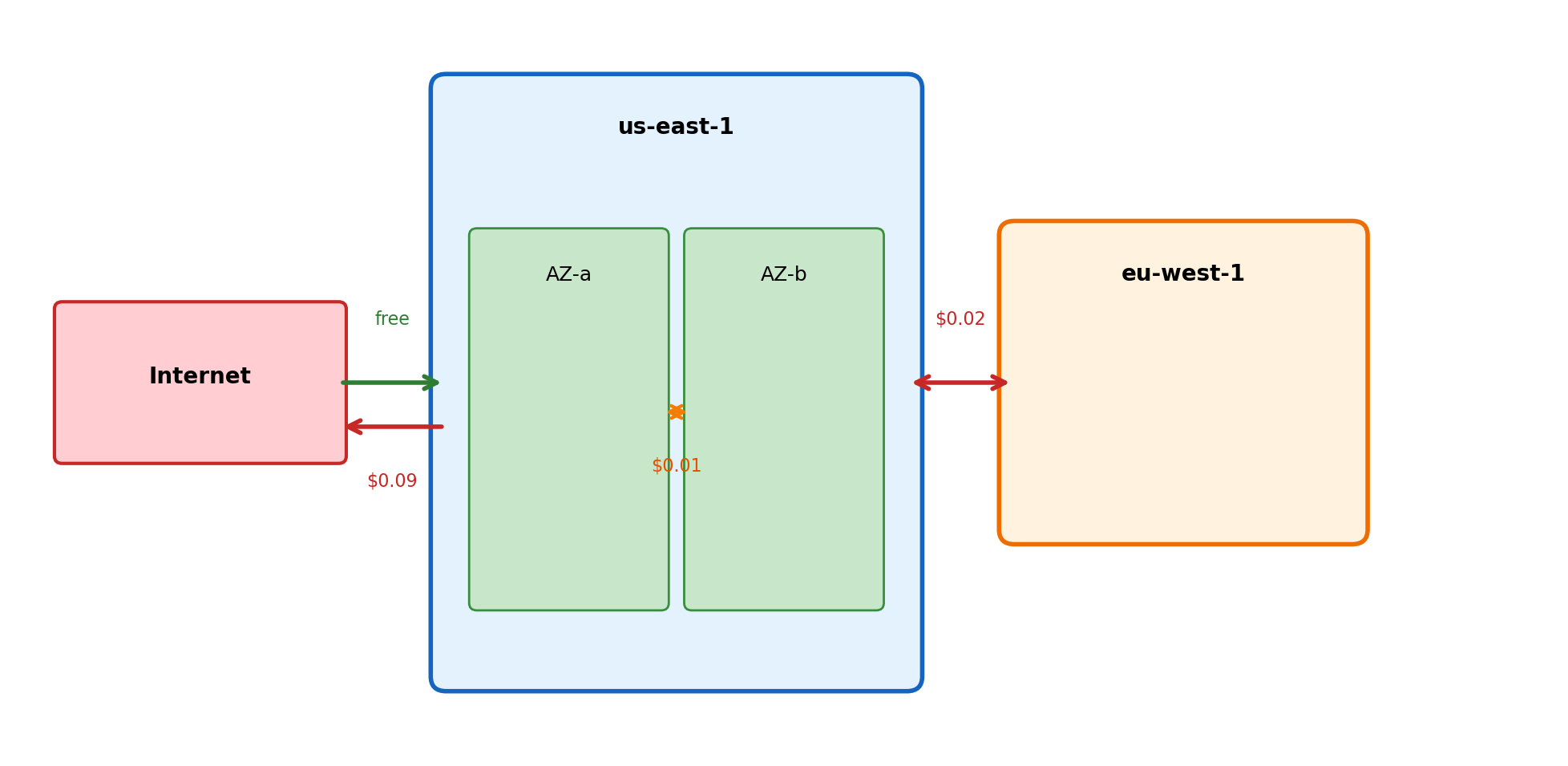

Data Transfer Costs

Data transfer charges based on movement, independent of the resources involved:

| Transfer | Price |

|---|---|

| Inbound from internet | Free |

| Outbound to internet | $0.09/GB |

| Between regions | $0.02/GB |

| Between AZs (same region) | $0.01/GB each direction |

| Within same AZ | Free |

| To S3/DynamoDB (same region) | Free |

Architectures that move large amounts of data across regions or to the internet accumulate transfer costs.

Free Tier

New AWS accounts receive a free tier for 12 months from account creation:

| Service | Monthly Allowance |

|---|---|

| EC2 | 750 hours of t3.micro |

| EBS | 30 GB of gp2/gp3 |

| S3 | 5 GB storage, 20,000 GET, 2,000 PUT |

| RDS | 750 hours of db.t3.micro |

| Data transfer | 100 GB outbound |

The 750-hour boundary:

One month ≈ 730 hours. The free tier covers approximately one t3.micro instance running continuously.

1 × t3.micro × 24h × 31d = 744 hours → within free tier

2 × t3.micro × 24h × 31d = 1,488 hours → 738 hours charged

1 × t3.small × 24h × 31d = 744 hours → all hours charged (t3.small not covered)Free tier applies to specific instance types. A t3.small incurs full charges regardless of free tier status.

Cost Monitoring

AWS provides mechanisms for tracking costs:

Billing Dashboard

Current month charges by service. Updated multiple times daily.

Cost Explorer

Historical cost data, filtering by service/region/tag, forecasting based on current usage patterns.

Budgets

Configurable thresholds with alert notifications. Set a monthly budget, receive email when approaching or exceeding it.

These mechanisms surface cost information. The billing model is pay-as-you-go—charges accumulate automatically. Monitoring makes accumulation visible.

ML System Design on AWS

From Local to Distributed

Your laptop runs ML training as a single process. Data, compute, and storage are all local.

Local training

data = pd.read_csv('dataset.csv') # Local disk

model = train(data) # Local CPU/GPU

torch.save(model, 'model.pth') # Local diskEverything shares memory, disk, and failure fate. If the process crashes, everything stops together. If the disk fails, you lose data and model.

One machine, one failure domain.

Distributed training

data = load_from_s3('bucket', 'data.csv') # Network call

model = train(data) # EC2 instance

save_to_s3(model, 'bucket', 'model.pth') # Network callComponents are networked. S3 can fail while EC2 runs. EC2 can terminate while S3 persists. Network can drop between them.

Data outlives compute. Compute is ephemeral. Network connects (and separates) them.

Where Latency Hides

Every arrow in your architecture diagram is network latency.

Local operations

| Operation | Time |

|---|---|

| Read 1MB from SSD | 1 ms |

| Load pandas DataFrame | 10 ms |

| PyTorch forward pass | 5 ms |

| Write checkpoint to disk | 2 ms |

Total per batch: ~20 ms. Predictable. Consistent.

With S3 in the loop

| Operation | Time |

|---|---|

| Fetch 1MB from S3 | 20–50 ms |

| Load pandas DataFrame | 10 ms |

| PyTorch forward pass | 5 ms |

| Write checkpoint to S3 | 30–100 ms |

Total per batch: 65–165 ms. Variable. Depends on network.

If you checkpoint every batch, you’ve added 3–5× overhead. Checkpoint every 100 batches instead.

Design for latency: batch S3 operations, prefetch data, checkpoint strategically.

Where Failures Happen

Distributed systems fail partially. Each component fails independently.

Independent failure domains

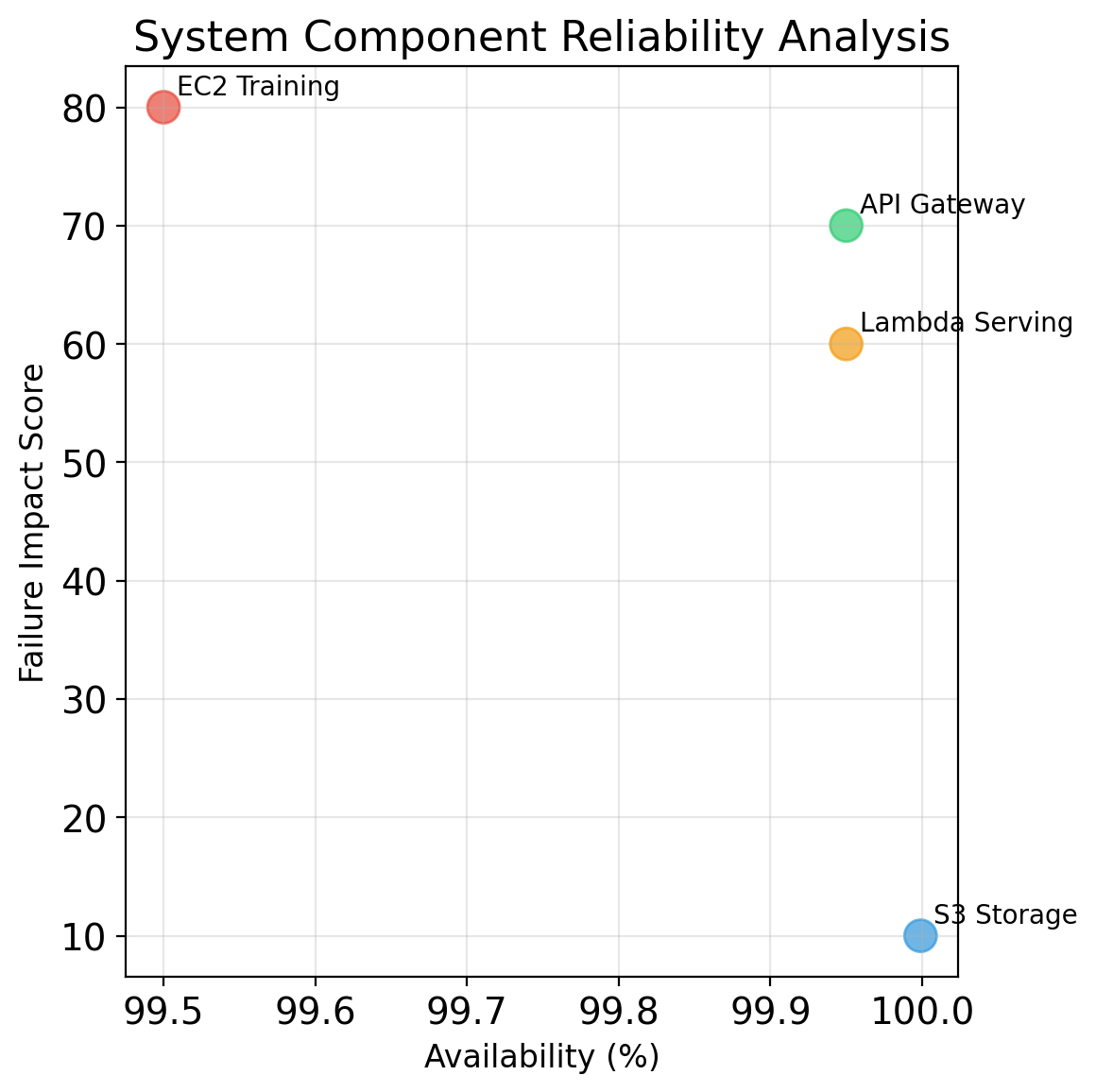

- S3: Available (11 nines durability), but individual requests can fail transiently

- EC2: Your instance can terminate (spot reclamation, hardware failure, your bug)

- Network: Packets drop, connections timeout, DNS fails

- Your code: Exceptions, OOM, infinite loops

S3 doesn’t know your EC2 instance crashed. EC2 doesn’t know S3 returned an error. You must handle the boundaries.

Failure scenarios

| Event | Data | Model | Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC2 terminates | Safe (S3) | Lost (if not saved) | Lost |

| S3 request fails | Retry works | Retry works | Continues |

| OOM on EC2 | Safe (S3) | Lost (if not saved) | Lost |

| Network partition | Safe (S3) | Stuck | Stuck |

The pattern: S3 is durable, EC2 is ephemeral. Save state to S3 frequently enough that losing EC2 is recoverable.

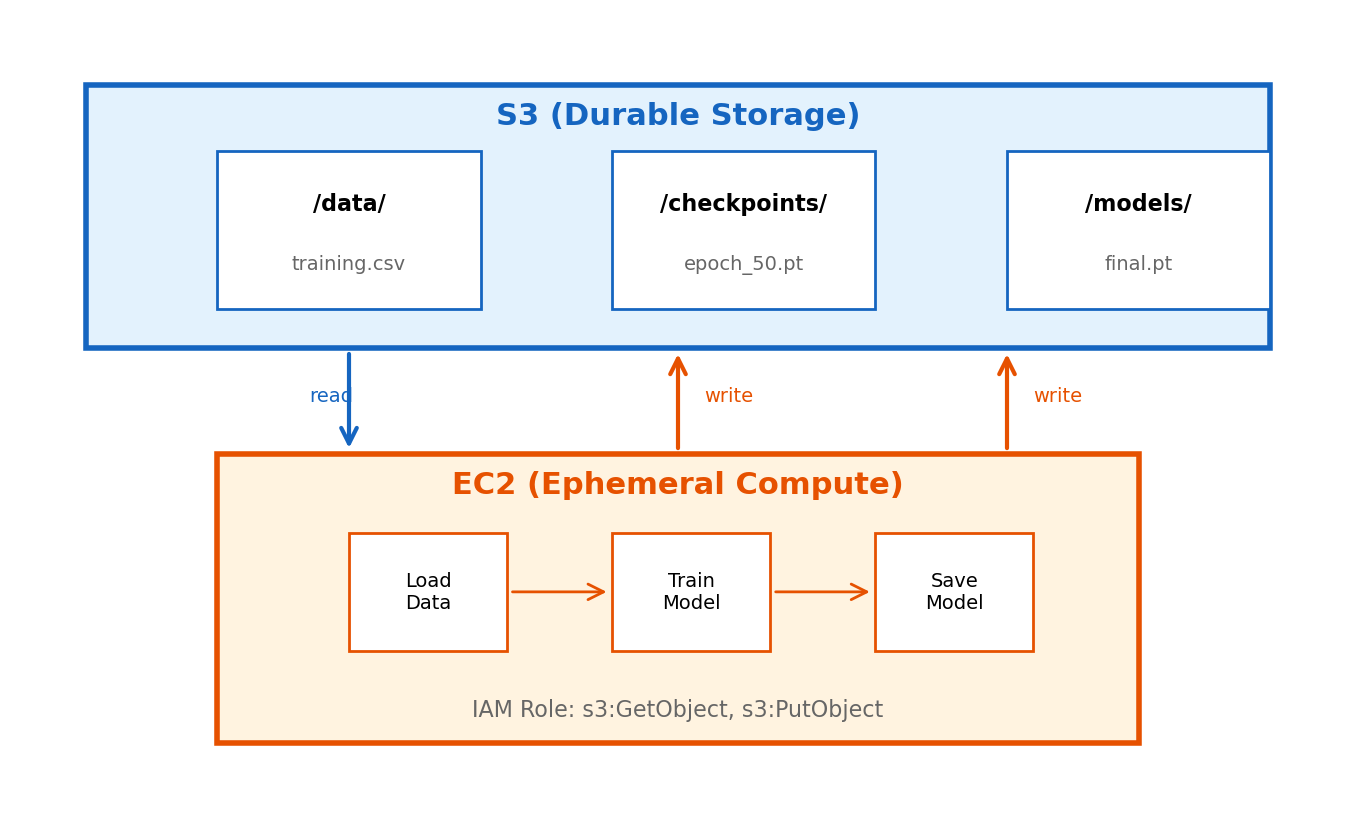

Data Flow Architecture

S3 is the durable integration point. EC2 is stateless compute.

Data flow pattern

- EC2 reads training data from S3

- EC2 processes (trains model)

- EC2 writes checkpoints and final model to S3

Why this works

- S3 is durable — data survives EC2 termination

- EC2 is ephemeral — no state lives only on the instance

- If EC2 terminates: launch new instance, load last checkpoint, continue

Recovery

No state is lost because state lives in S3, not EC2.

Credential Flow

EC2 instances assume IAM roles. No access keys in code.

How it works

- EC2 instance launches with an instance profile

- Instance profile contains an IAM role

- Role has policies granting S3 access

- SDK queries instance metadata for temporary credentials

- SDK signs S3 requests with those credentials

- Credentials rotate automatically (no management)

What the role needs

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::training-bucket/*"

]

},

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::training-bucket"

}

]

}Bucket ARN for ListBucket. Object ARN (with /*) for GetObject/PutObject. This distinction matters.

Checkpoint Strategy

Checkpoints convert EC2 failures from catastrophic to recoverable.

Without checkpoints

- Training runs for 10 hours

- EC2 spot instance reclaimed at hour 8

- Result: 8 hours of compute wasted, start over

With checkpoints every epoch

- Training runs for 10 hours (100 epochs)

- Checkpoint saved to S3 after each epoch

- EC2 reclaimed at hour 8 (epoch 80)

- New instance loads epoch 80 checkpoint

- Result: 20 minutes lost, not 8 hours

Checkpoint frequency trade-off

| Frequency | S3 Writes | Recovery Loss | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Every batch | 10,000/epoch | Seconds | High (latency) |

| Every epoch | 100 total | Minutes | Low |

| Every 10 epochs | 10 total | ~1 hour | Minimal |

Choose based on:

- Training cost per hour (expensive = checkpoint more)

- S3 write latency tolerance

- Spot interruption frequency (2 min warning)

For spot instances: checkpoint at least every 2 minutes or on interruption signal.

Idempotent Operations

Operations should be safe to retry. Network failures mean you often don’t know if something succeeded.

The problem

# Upload model to S3

s3.put_object(Bucket='b', Key='model.pt', Body=data)

# Network timeout. Did it succeed?

# If you retry and it already succeeded, is that okay?For S3 put_object: yes, safe to retry. Same key overwrites with same content. No harm.

Design for idempotency

Safe to retry:

- Writing a file to a deterministic path

- Overwriting a checkpoint with newer version

- Reading data (no side effects)

Not safe to retry (without care):

- Incrementing a counter

- Appending to a log

- Sending a notification

Pattern: Use deterministic keys

Cost-Aware Design

Three things cost money: compute time, storage, and data transfer.

Compute (EC2)

- Billed per second (minimum 60 seconds)

- Running instance = paying, even if idle

- Terminated instance = not paying

- Stopped instance = still paying for EBS storage

Design response: Terminate when done. Use spot instances for fault-tolerant work. Don’t leave instances running overnight.

Storage (S3)

- Billed per GB-month

- Also billed per request (but usually negligible)

- Data persists until you delete it

Design response: Delete intermediate files. Use lifecycle policies for old checkpoints.

Data transfer

| Path | Cost |

|---|---|

| Into AWS | Free |

| Within AZ | Free |

| Cross-AZ (same region) | $0.01/GB |

| Cross-region | $0.02–0.09/GB |

| Out to internet | $0.09/GB |

Design response: Keep data and compute in the same region. Avoid repeatedly downloading large datasets from S3 to local machine.

Example costs for a training job

| Resource | Usage | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| EC2 p3.2xlarge | 8 hours | $24.48 |

| S3 storage | 50 GB/month | $1.15 |

| Data transfer | Within region | $0 |

Compute dominates. Optimize instance usage first.

AWS Billing is Real

AWS charges your credit card. Resources cost money from the moment they’re created.

What catches students

| Mistake | Cost |

|---|---|

| p3.2xlarge left running over weekend | $220 |

| Forgot to delete 500GB S3 bucket | $12/month forever |

| Auto-scaling launched 20 instances | $50/hour |

| Cross-region replication enabled | $45 transfer |

These are real examples from students.

Protection measures

- Set billing alerts ($10, $25, $50 thresholds)

- Check running instances daily during coursework

- Terminate (not just stop) instances when done

- Delete S3 buckets you’re not using

Free tier limits

| Service | Free Amount |

|---|---|

| EC2 t2.micro | 750 hours/month |

| S3 | 5 GB storage |

| Data transfer out | 100 GB/month |

Beyond free tier, you pay.

Safe practices

- Use

t3.microfor development/testing - Use GPU instances only when actually training

- Set up billing alerts before launching anything

- When in doubt, terminate everything

S3 Bucket Organization

Structure enables automation. Predictable paths enable programmatic access.

ml-project-{username}/

├── data/

│ ├── raw/ # Original, immutable

│ │ └── dataset_v1.csv

│ └── processed/ # Transformed, ready for training

│ ├── train.parquet

│ └── test.parquet

├── checkpoints/

│ └── experiment_001/

│ ├── epoch_0010.pt

│ ├── epoch_0020.pt

│ └── epoch_0030.pt

├── models/

│ └── experiment_001/

│ └── final.pt

└── logs/

└── experiment_001/

└── training.logConventions that help:

- Zero-pad numbers (

epoch_0010notepoch_10) — sorts correctly - Include experiment ID — enables multiple concurrent runs

- Separate raw from processed — raw is immutable backup

- Separate checkpoints from final models — checkpoints are disposable

Putting It Together

A training job as cloud operations:

Startup

- EC2 instance launches with IAM role

- SDK discovers credentials via instance metadata

- Download training data from S3

- Download latest checkpoint (if resuming)

Training loop

- Train for N epochs

- After each epoch: save checkpoint to S3

- If spot interruption warning: save immediately, exit gracefully

Completion

- Save final model to S3

- Instance terminates (or you terminate it)

- Model persists in S3 for serving

What can fail and what happens

| Failure | Impact | Recovery |

|---|---|---|

| S3 read fails | Training can’t start | Retry with backoff |

| S3 write fails | Checkpoint lost | Retry; if persistent, alert |

| EC2 terminates | Training stops | New instance + last checkpoint |

| OOM | Process crashes | Reduce batch size, restart |

| Code bug | Process crashes | Fix bug, restart from checkpoint |

Every failure mode has a recovery path because:

- State lives in S3, not EC2

- Checkpoints are frequent enough

- Operations are idempotent

Implementation Patterns

S3: Reading Data

Two approaches: download to file, or stream into memory.

Download to local file

import boto3

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# Download to local filesystem

s3.download_file(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='data/training.csv',

Filename='/tmp/training.csv'

)

# Then read locally

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('/tmp/training.csv')Use when:

- File is large (streaming would hold in memory)

- You need to read the file multiple times

- Library expects a file path

Stream directly into memory

import boto3

import pandas as pd

from io import BytesIO

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# Get object returns a streaming body

response = s3.get_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='data/training.csv'

)

# Read directly into pandas

df = pd.read_csv(response['Body'])Use when:

- File fits comfortably in memory

- You only need to read it once

- You want to avoid disk I/O