Relational Databases and SQL

EE 547 - Unit 4

Spring 2026

Outline

Model and Language

- Durable shared state and structured access

- Declarative vs procedural queries

- Tables, types, keys, and constraints

- SELECT, JOIN, aggregation

- Subqueries, CTEs, window functions

Design and Operations

- ER modeling, cardinality, and implementation

- Redundancy, anomalies, and normal forms

- Denormalization and the NoSQL connection

- ACID, isolation levels, and locking

- B-trees, composite indexes, and write costs

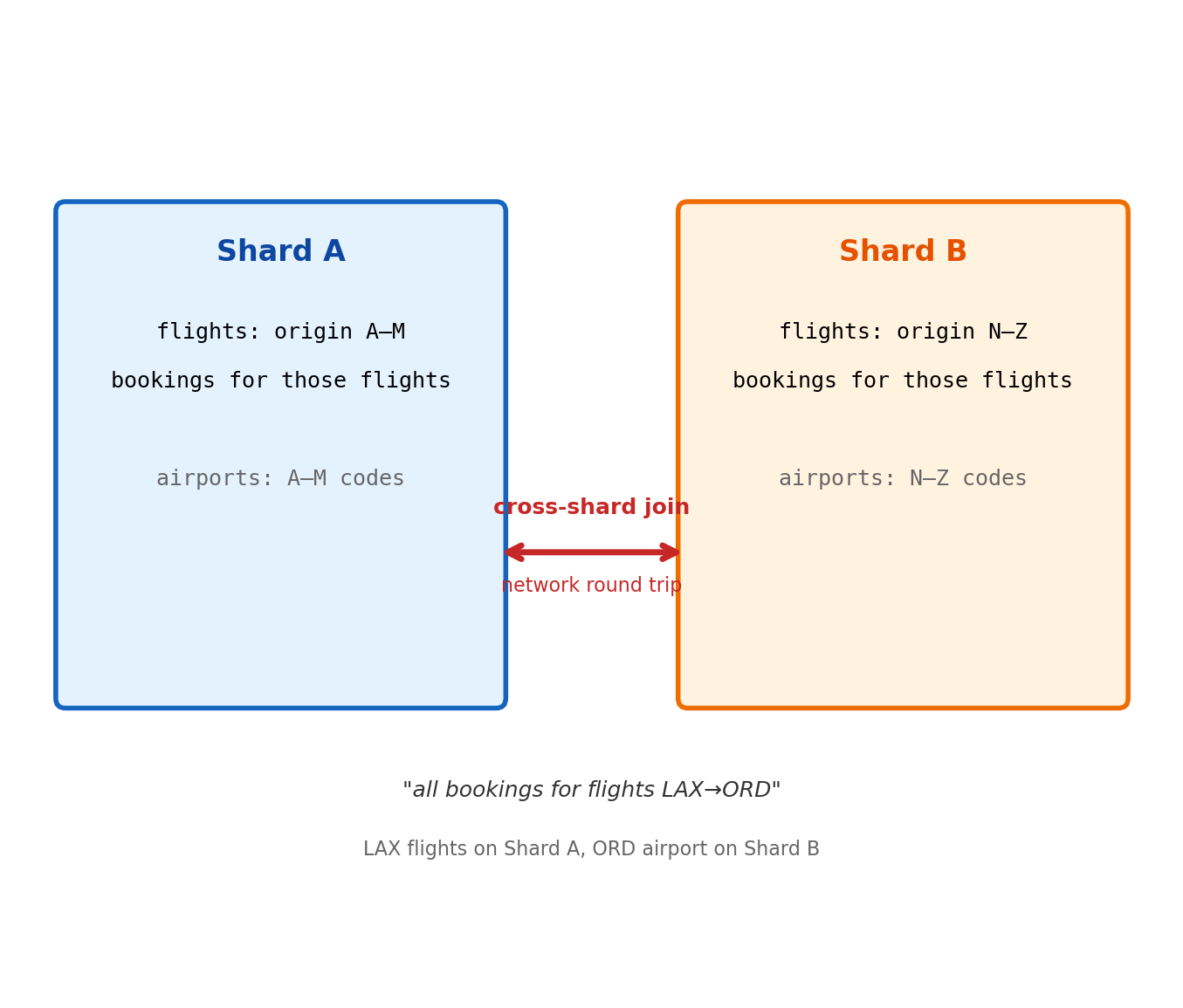

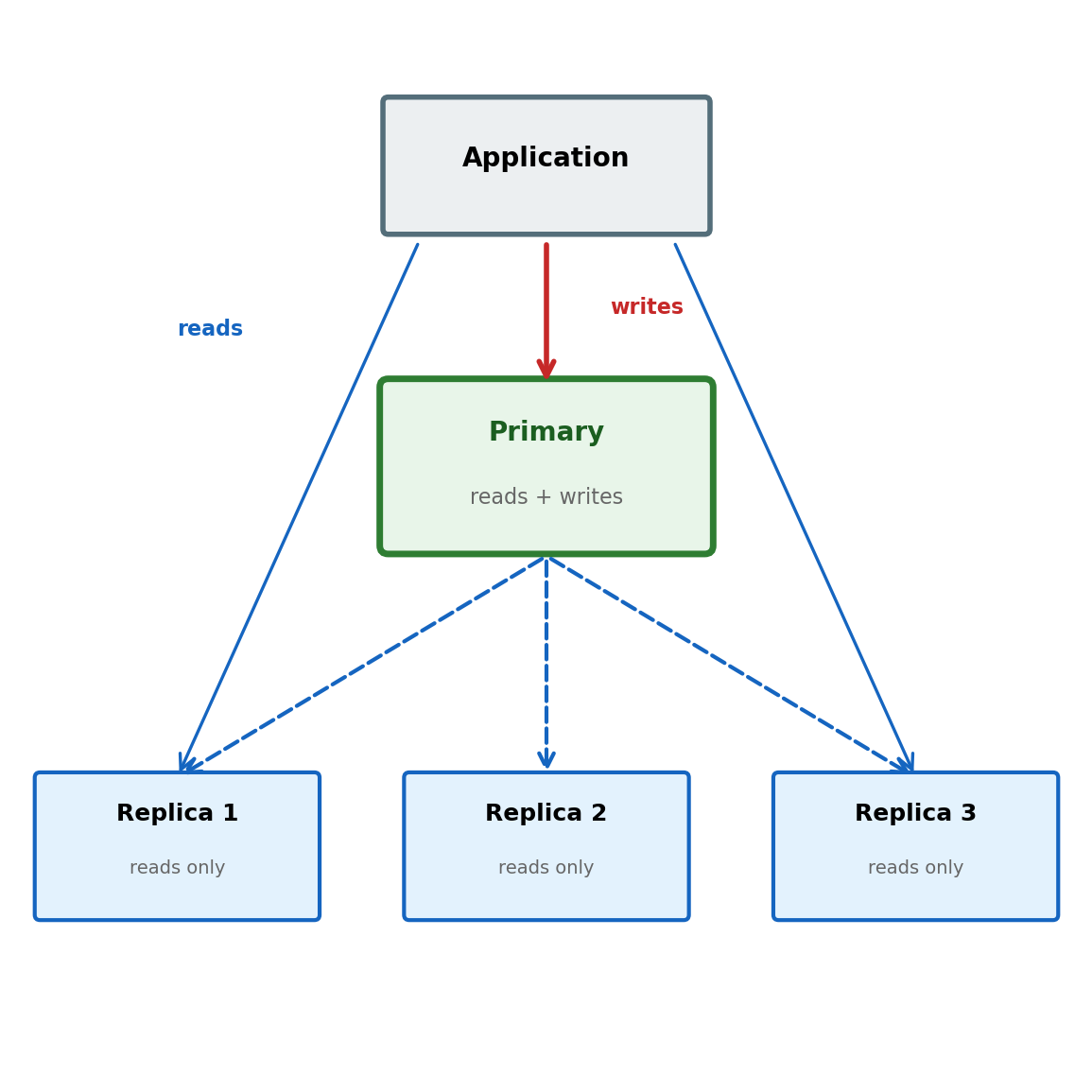

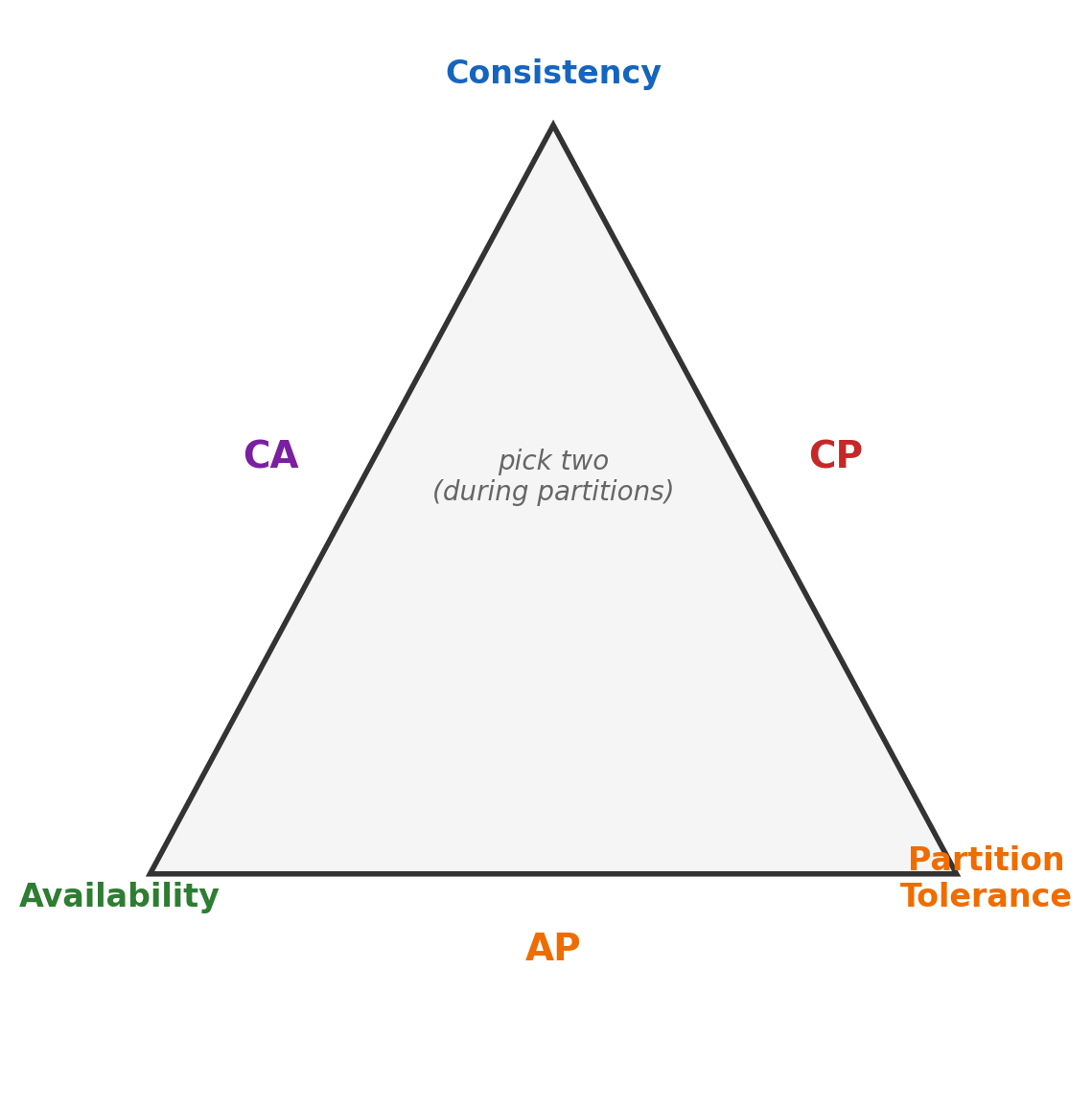

- Vertical limits, sharding, and CAP

Persistent Structured Storage

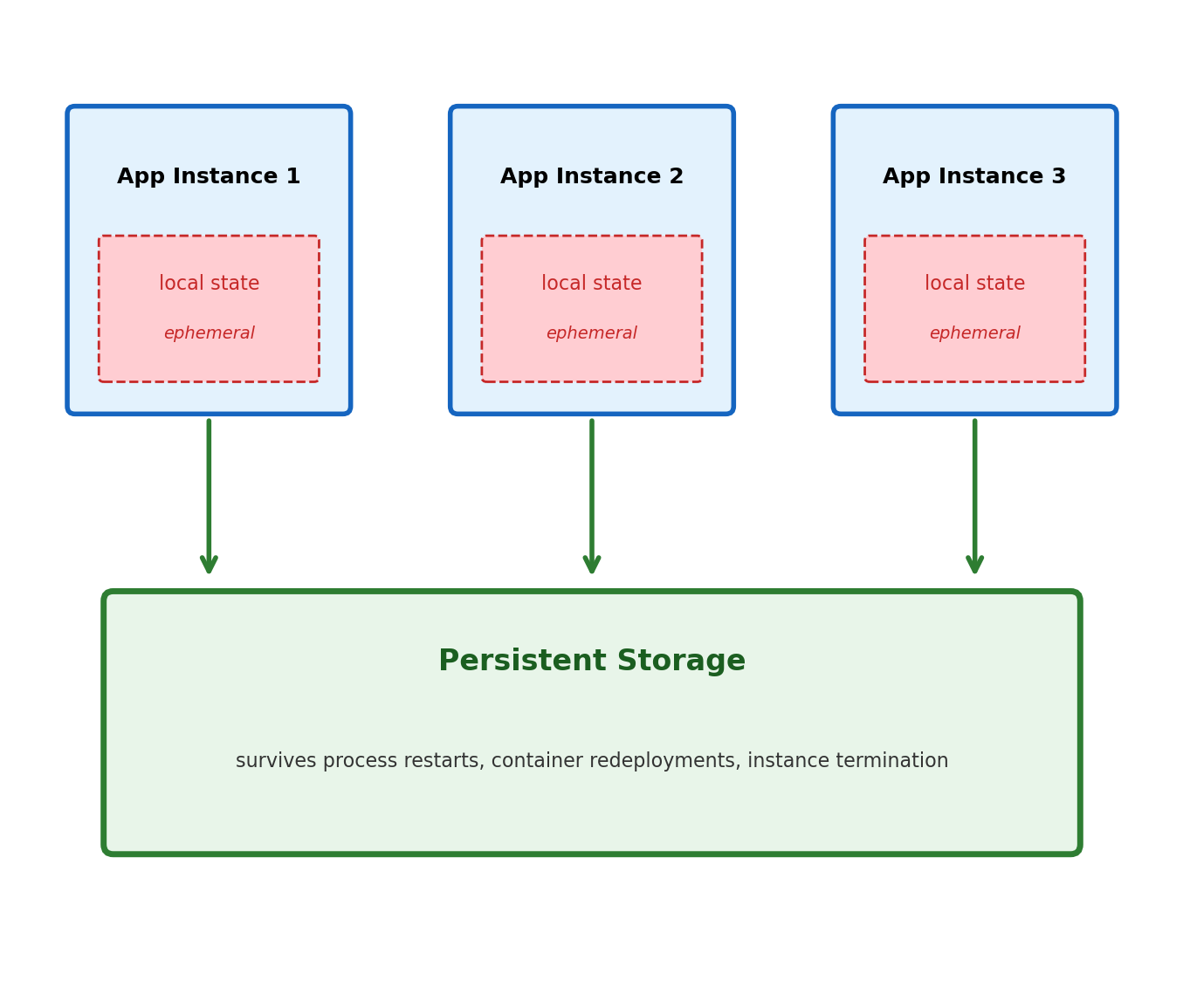

Application State Lives in Process Memory

Every application maintains state while running. A web server tracks active connections. An application server holds session data, cached computations, in-flight request context.

This state exists only in process memory.

Python dictionaries, object attributes, class instances — all reside in the process heap

A running container writes temporary files to its writable layer

Redis holds its dataset in RAM

Application logs accumulate in local buffers

When the process exits, the memory is reclaimed

When the container restarts, the writable layer is replaced

When the instance terminates, local storage is gone

This is by design — stateless processes are straightforward to scale, replace, and restart. But the data they operated on must exist somewhere that outlives any individual process:

- The actual records

- The accumulated results

- The shared state

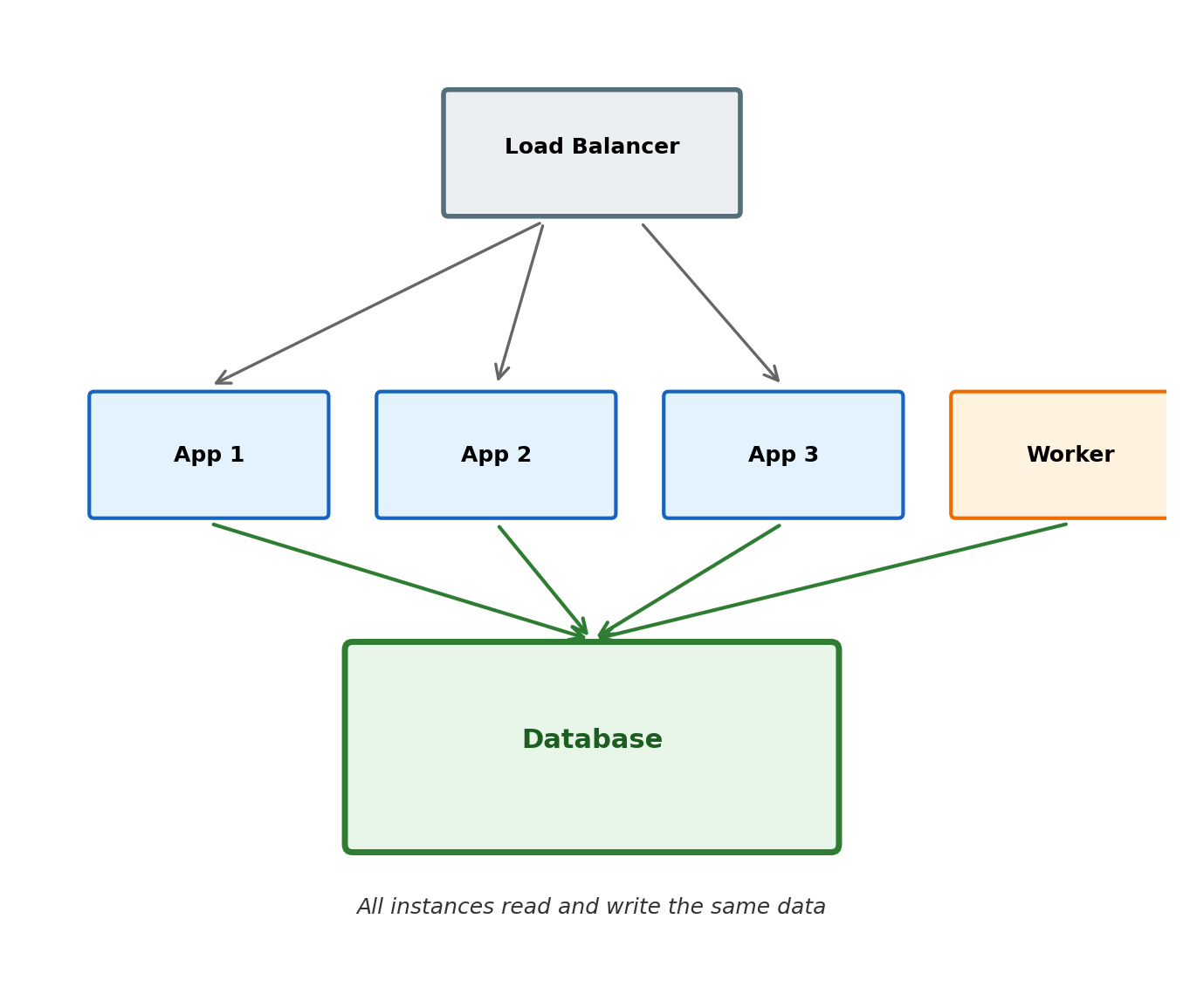

Multiple Processes Need Access to the Same Data

A typical application runs multiple instances of the same service behind a load balancer. Each instance handles a fraction of incoming requests.

Shared state is the norm, not the exception.

- User A creates an account through instance 1. User B looks up that account through instance 3. Both need access to the same user record.

- A background worker processes jobs queued by the web tier. The worker reads data the web tier wrote.

Example: an airline booking system runs 20 application servers. All 20 must see the same seat map — a seat sold through one instance must immediately be unavailable to all others.

Each process cannot maintain its own copy. Copies diverge immediately under concurrent writes. Reconciling divergent copies is one of the hardest problems in distributed systems.

Durable Writes Survive the Process That Made Them

Data written to a persistent store must survive the failure of the process that wrote it — a stronger guarantee than “data is saved to a file.”

Process crash — the application segfaults mid-operation. A kill -9 terminates it without cleanup. Completed writes are still present when the replacement process starts.

Container restart — a deployment rolls out new code. The orchestrator terminates the old container and starts a new one. Data written by the old version is available to the new version without any migration step.

Host failure — the physical server loses power. The disk may have had buffered writes that never been persisted. After recovery, committed data is intact because the database wrote it to a transaction log before acknowledging the commit.

An application that writes to a local file and calls flush() has no guarantee the data reached disk — the OS may buffer it. Databases use write-ahead logging (WAL) to close this gap: the commit is not acknowledged until the log entry is on stable storage.

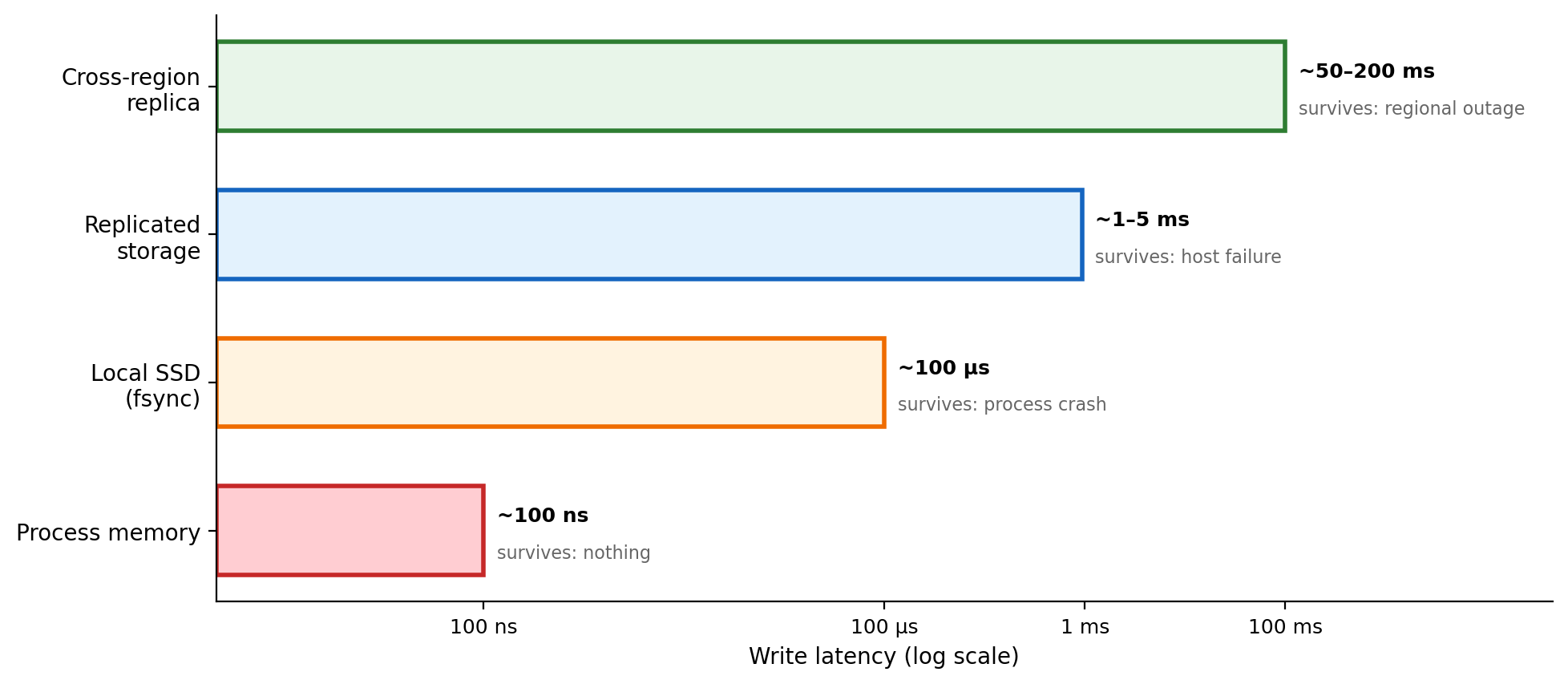

Durability Has Measurable Cost

Every level of durability corresponds to a specific mechanism. Stronger guarantees cost more time.

The gap between process memory (~100 ns) and a cross-region replica (~100 ms) is six orders of magnitude. A write that takes nanoseconds locally takes hundreds of milliseconds to guarantee survival of a regional outage.

Higher durability adds latency cost.

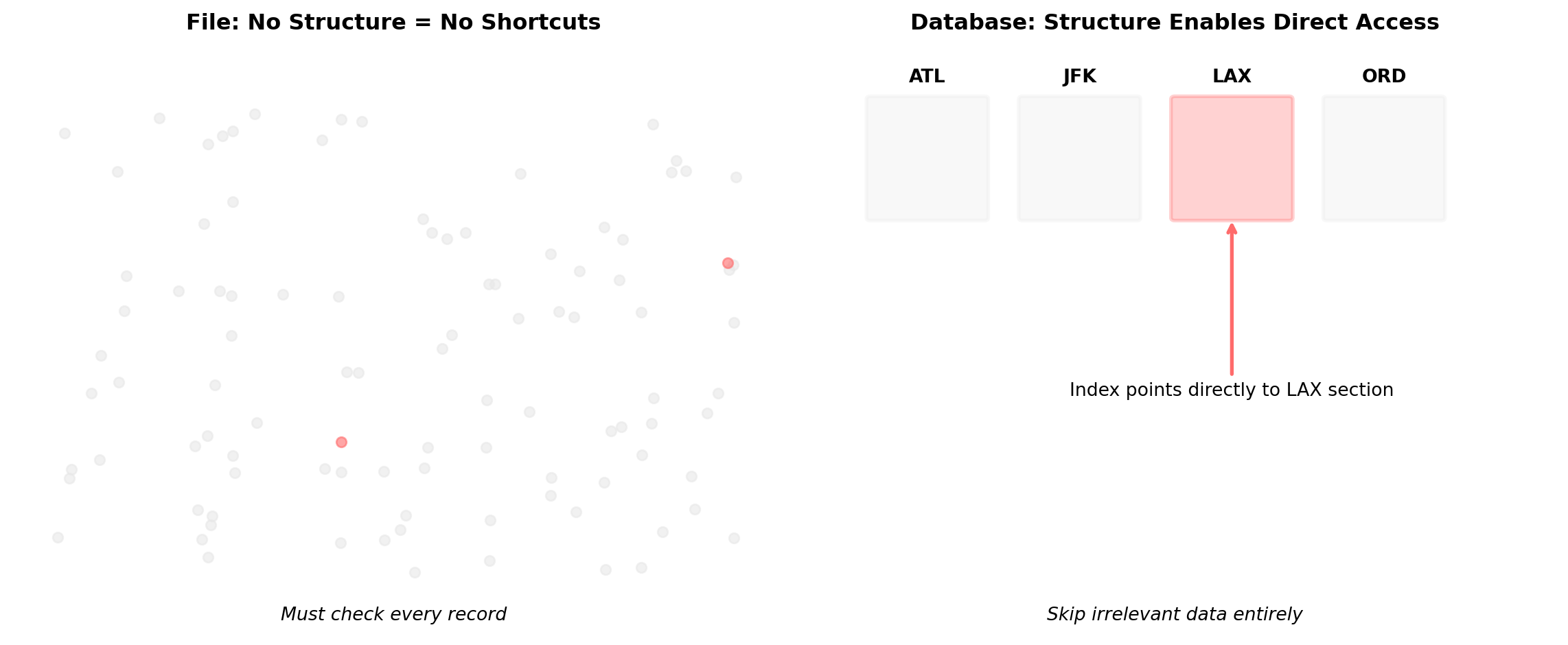

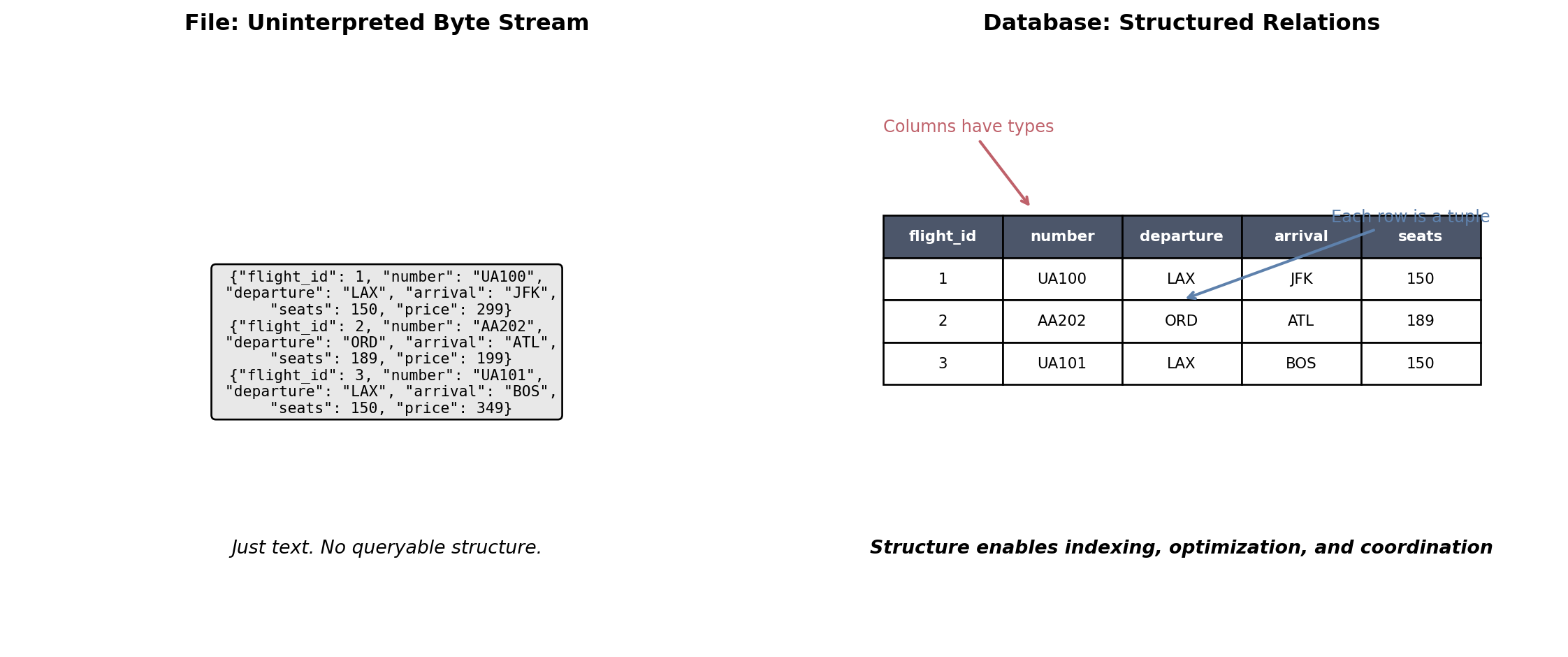

Unstructured Storage Forces Full Scans

An application that stores flight records as flat files — one JSON blob per flight, or a single CSV — must read and parse the entire dataset to answer any question about it.

File or object storage retrieves by name.

# S3: retrieve a known object

s3.get_object(Bucket='flights', Key='2026/02/lax-jfk.json')

# Filesystem: read a known file

open('/data/flights/2026/02/lax-jfk.json')The application must know which object to retrieve. There is no mechanism to ask the storage system for objects matching a condition.

“Which flights from LAX have available seats?”

- Download all flight objects

- Parse each one (JSON decode, CSV parse)

- Filter in application code

- 10 million records at 1 KB each = 10 GB transferred and parsed

The cost scales linearly with total data size, regardless of how selective the question is.

Structured Storage Knows the Shape of the Data

The storage system itself understands column names, types, and constraints. This knowledge is what enables selective access.

SELECT flight_number, departure_time, seats_remaining

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LAX'

AND seats_remaining > 0

AND departure_date = '2026-02-12';The database reads only matching records. With an index on (origin, departure_date), this touches a handful of disk pages regardless of total table size.

10 million records, same question: microseconds, reading kilobytes.

The database can do this because it knows:

originis a character column with an indexdeparture_dateis a date type, comparable with=seats_remainingis an integer, comparable with>- The table has statistics on value distribution that inform which access strategy is cheapest

Without database-level structure, every application is responsible for:

- Parsing and validating every record on read

- Ensuring consistency across related records

- Implementing its own search and filtering

- Preventing concurrent writes from corrupting shared files

Every application that accesses the data re-implements this logic. Each implementation is an opportunity for divergence.

Application A reads a flight record as JSON with departure_time as an ISO-8601 string. Application B reads the same file and parses it as a Unix timestamp. Both are “correct” until a timezone mismatch causes a booking for the wrong flight.

A database centralizes these responsibilities. The structure is defined once, enforced by the storage system, and consistent for every client that connects.

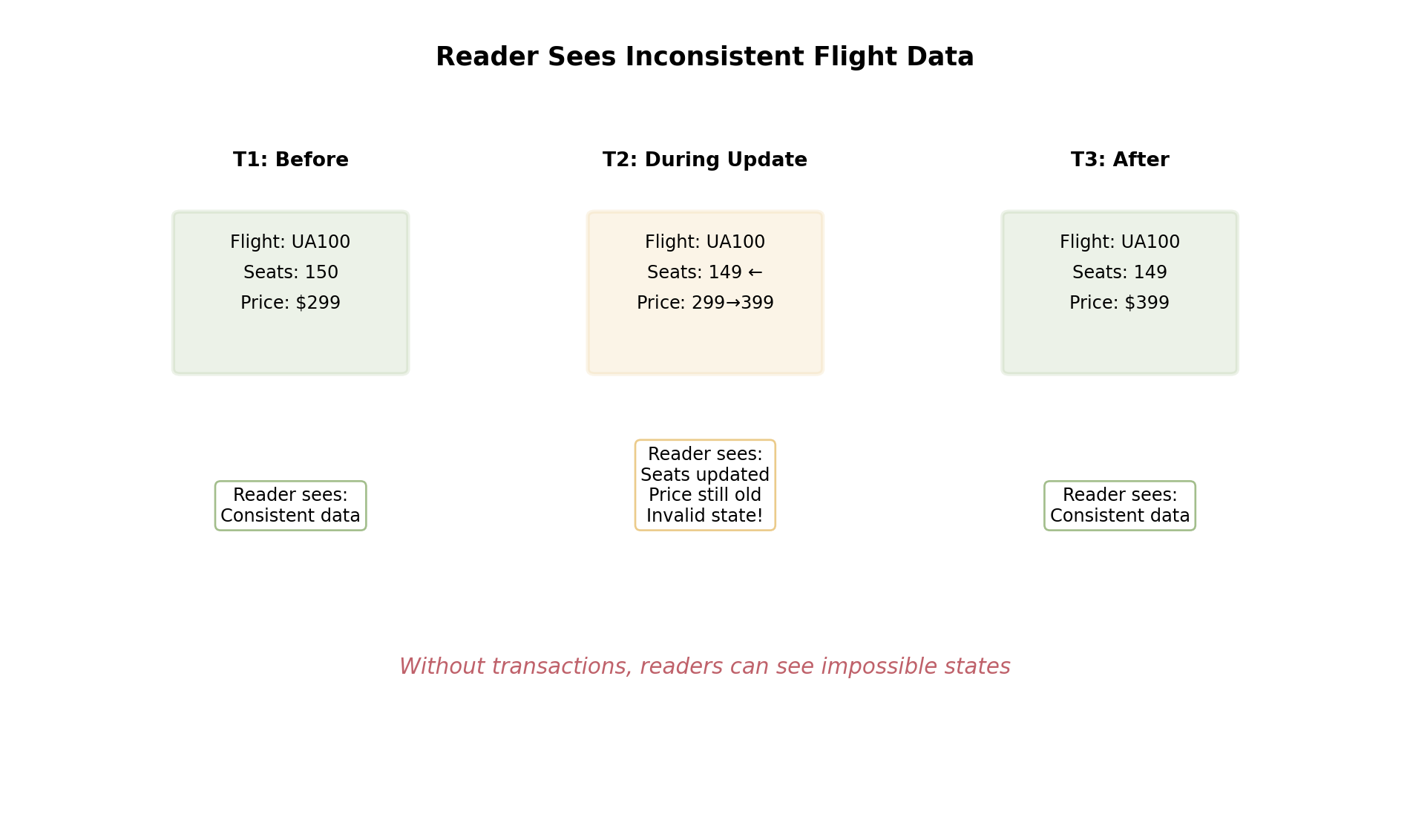

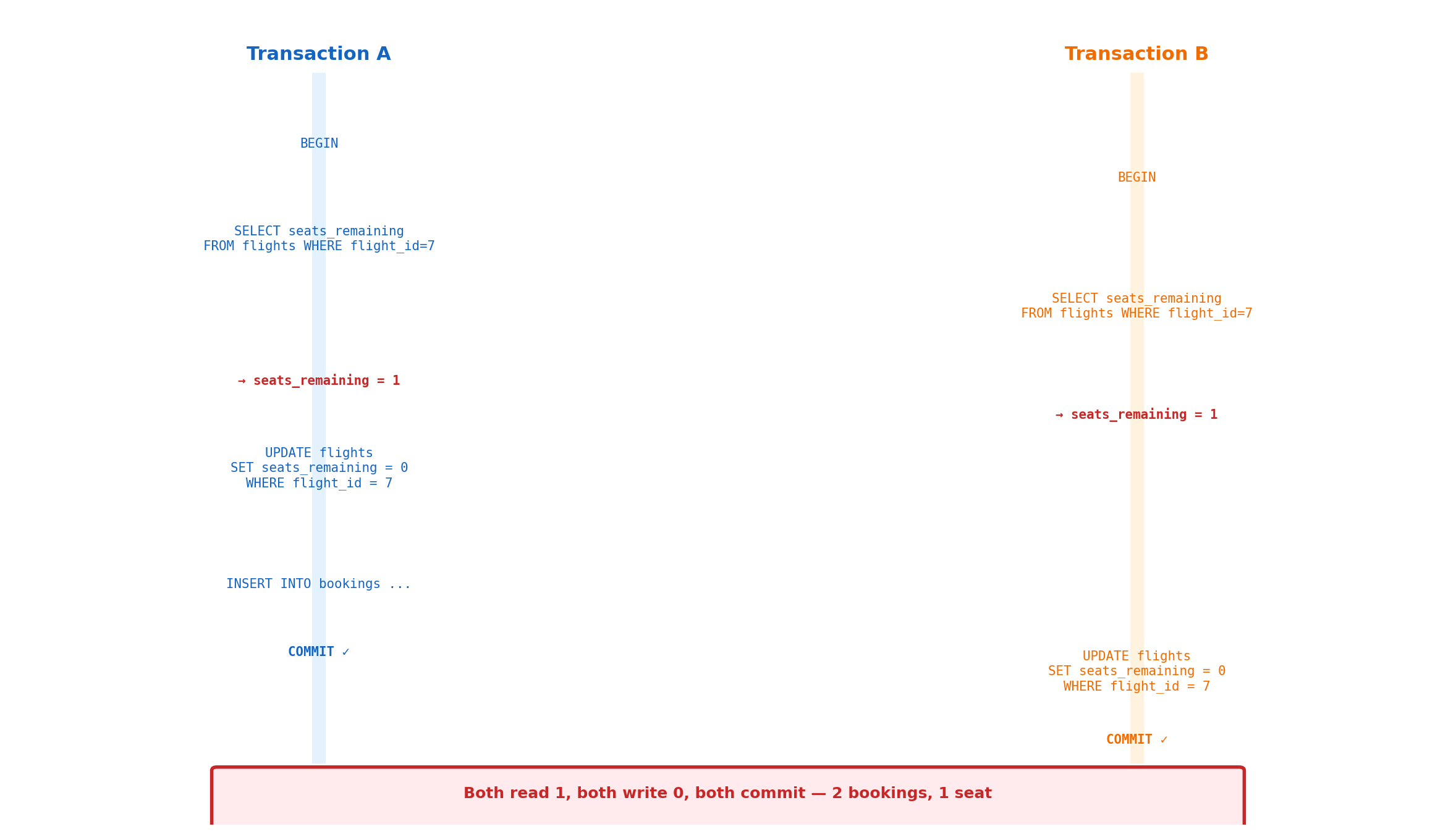

Concurrent Access Without Coordination Corrupts Data

Multiple processes writing to the same data simultaneously is the default operating condition for any shared storage system.

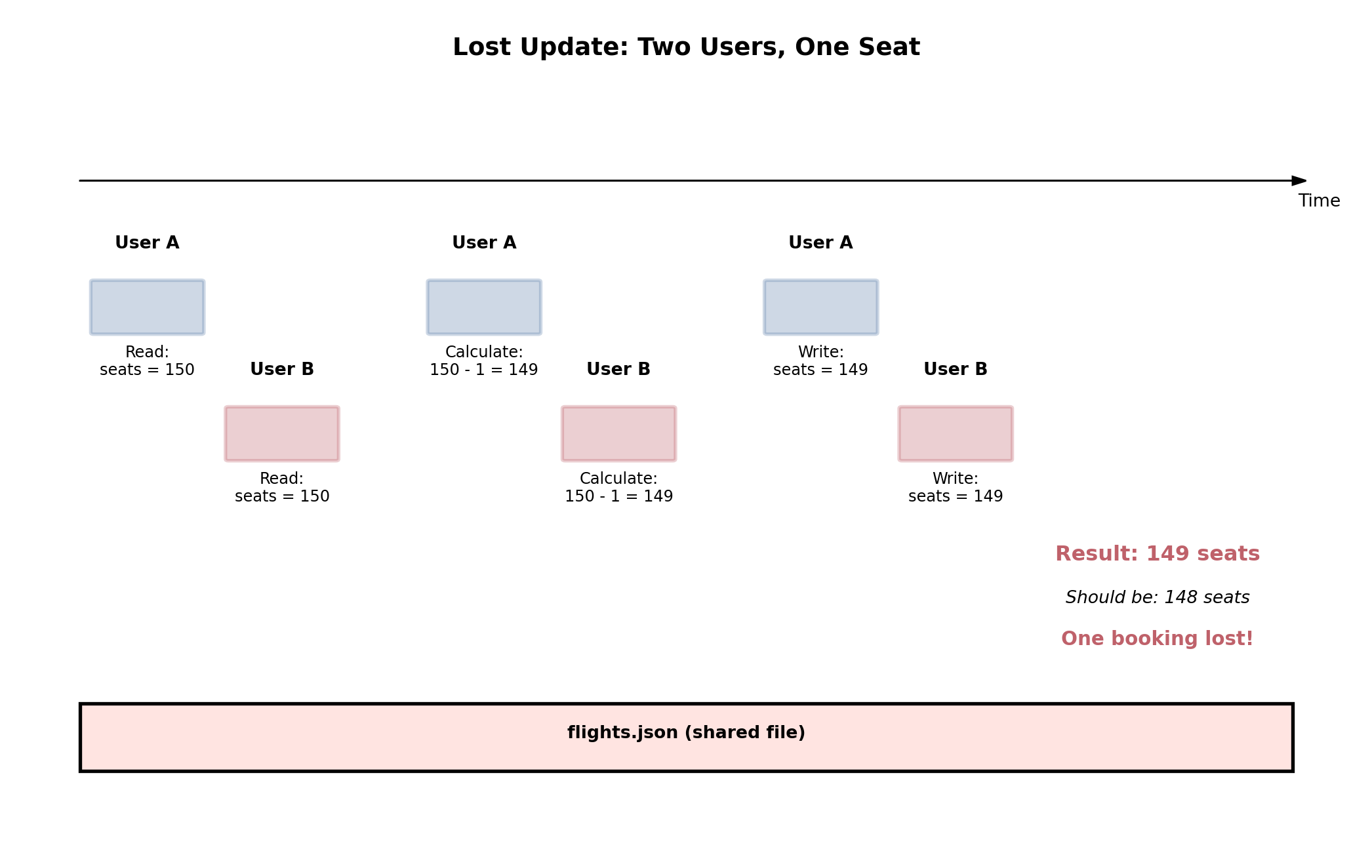

An airline booking system. Two users attempt to book the last seat on flight 547, at the same time, through different application servers:

- App server A reads seat count: 1 remaining

- App server B reads seat count: 1 remaining

- App server A writes: 1 - 1 = 0 remaining, confirms booking

- App server B writes: 1 - 1 = 0 remaining, confirms booking

Two confirmed bookings. One seat.

This is the lost update — a concurrency anomaly that occurs whenever read-then-write operations are not atomic. Both servers read the same value, both compute the same result, and the second write silently overwrites the first.

The anomaly is not caused by a bug in application logic. The code is correct for a single-writer system. It fails because the system has multiple writers and no coordination between them.

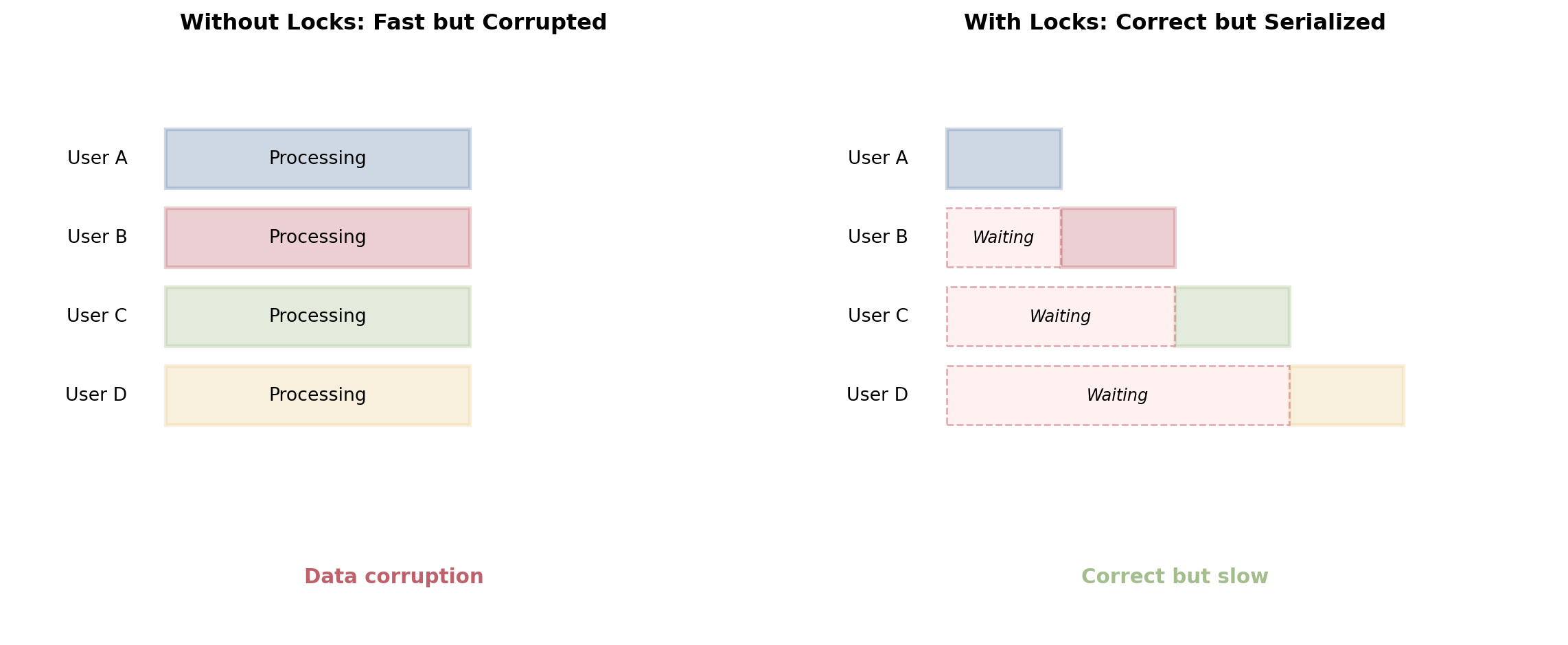

File Locking Does Not Scale

One workaround is file locking — flock() on Unix, LockFileEx() on Windows. One writer at a time.

File-level locking:

- Lock the entire flights file

- Read the seat count

- Update and write back

- Release the lock

This serializes all access. While one process holds the lock, every other process waits — including processes operating on completely unrelated flights.

A system with 10,000 flights and 100 concurrent users: every operation on every flight waits for a single global lock. Throughput falls.

Database row-level locking:

- Lock only the row for flight 547

- Other flights are unaffected

- Processes operating on different flights proceed concurrently

- The lock is held for milliseconds, not for the duration of a file I/O operation

Databases provide granular locking — down to individual rows — combined with transaction isolation that controls what concurrent readers can see. The coordination cost is proportional to actual contention, not to dataset size.

Replicating granular locking and transaction isolation on top of file storage means re-implementing substantial portions of a database engine.

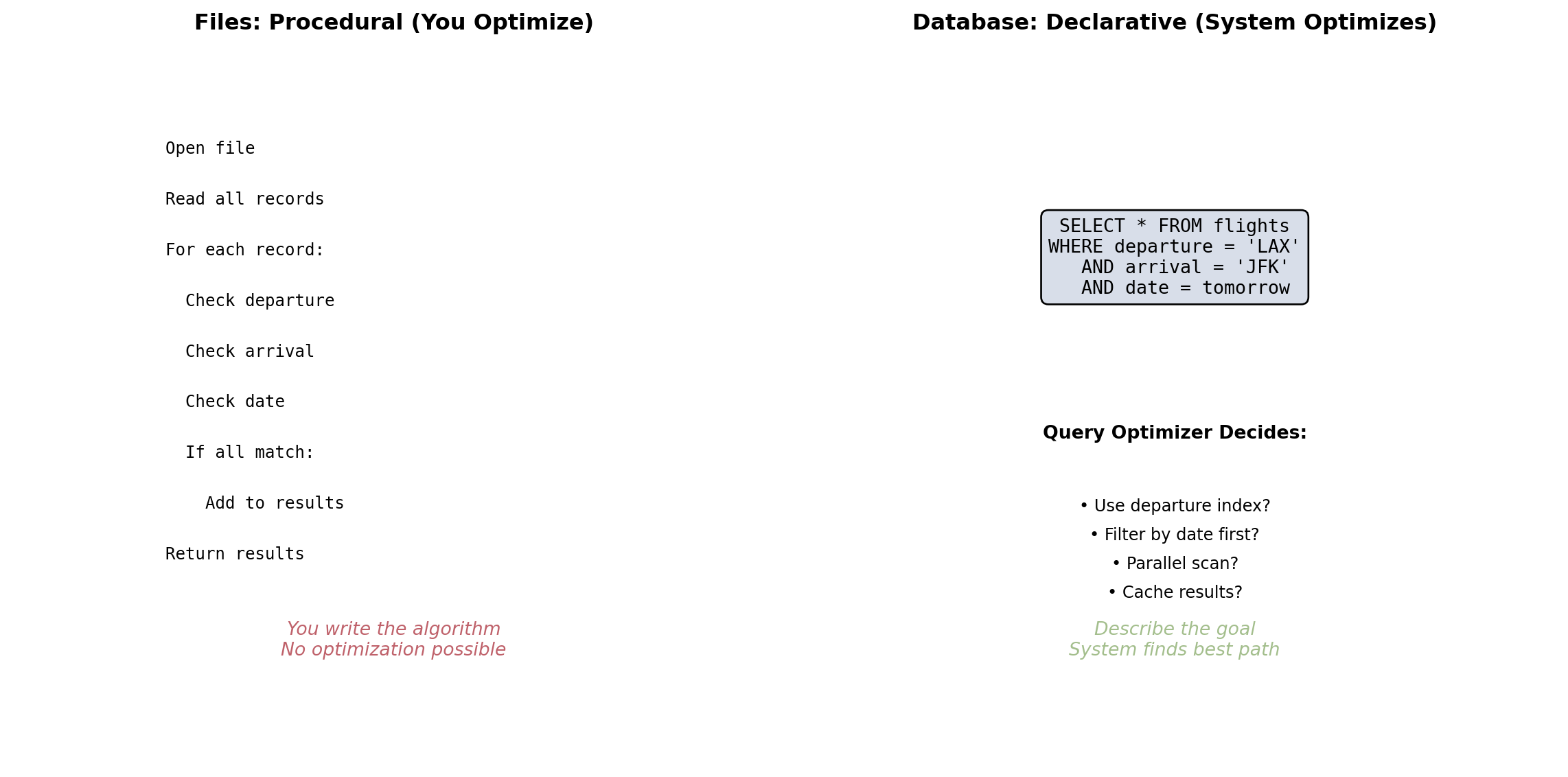

Procedural Data Access Binds Logic to Execution Strategy

When the application controls how data is accessed, the access strategy is embedded in the code.

# Find available flights from LAX on Feb 12

results = []

for flight in all_flights: # iterate every record

if flight['origin'] == 'LAX' \

and flight['seats'] > 0 \

and flight['date'] == '2026-02-12':

results.append(flight)The strategy is fixed:

- Sequential scan — always reads every record

- Application bears the full cost of filtering

- If data grows 100x, this code runs 100x slower

- No way to use indexes, caches, or pre-sorted data without rewriting the loop

Changing access patterns requires changing code:

- Want to speed up LAX lookups? Build an in-memory dictionary keyed by origin. Rewrite the query logic.

- Want to support date-range queries? Sort the data by date. Rewrite again.

- Want to join flights with bookings? Nested loops, careful key matching. More code, more bugs.

Every performance improvement is a code change. Every code change is a testing and deployment cycle.

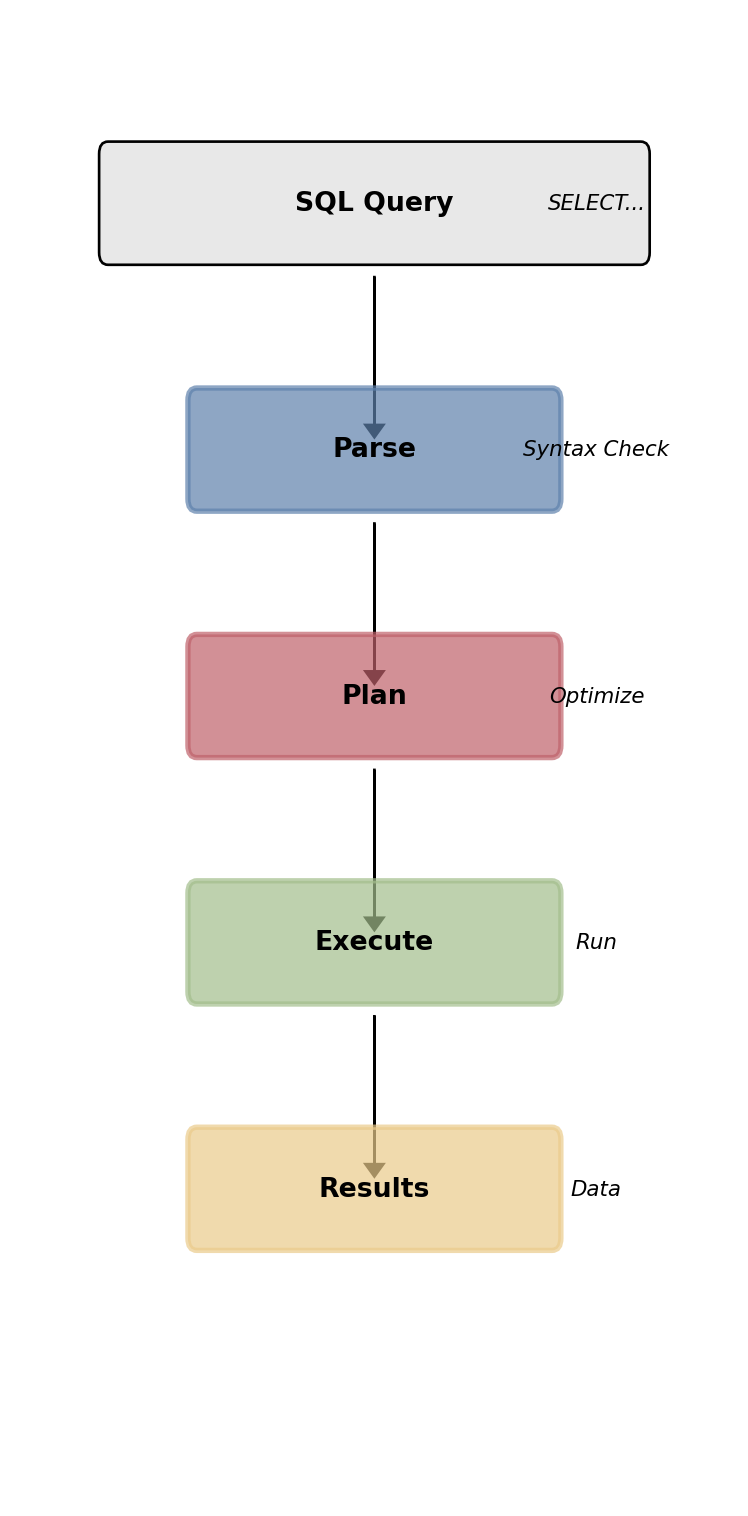

Declarative Queries Let the Database Choose the Strategy

SQL specifies what data to return, not how to find it.

SELECT flight_number, departure_time, seats_remaining

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LAX'

AND seats_remaining > 0

AND departure_date = '2026-02-12';The query optimizer evaluates execution strategies:

- No index on

origin? Sequential scan. - Index on

originexists? Index lookup, then filter. - Index on

(origin, departure_date)? Composite index lookup — reads only the exact set of matching rows.

Same SQL. The optimizer picks the cheapest plan based on:

- Available indexes

- Table size and row count estimates

- Column value distribution (selectivity statistics)

- Available memory for sorting and hashing

Performance improves without application changes.

An index is added on origin:

- The optimizer detects the new index

- Switches from sequential scan to index lookup

- Query goes from scanning 10 million rows to reading a few hundred

- No application code changes

This separation — application specifies intent, database chooses execution — is what allows databases to optimize independently of the applications that use them. It is the central architectural insight of the relational model.

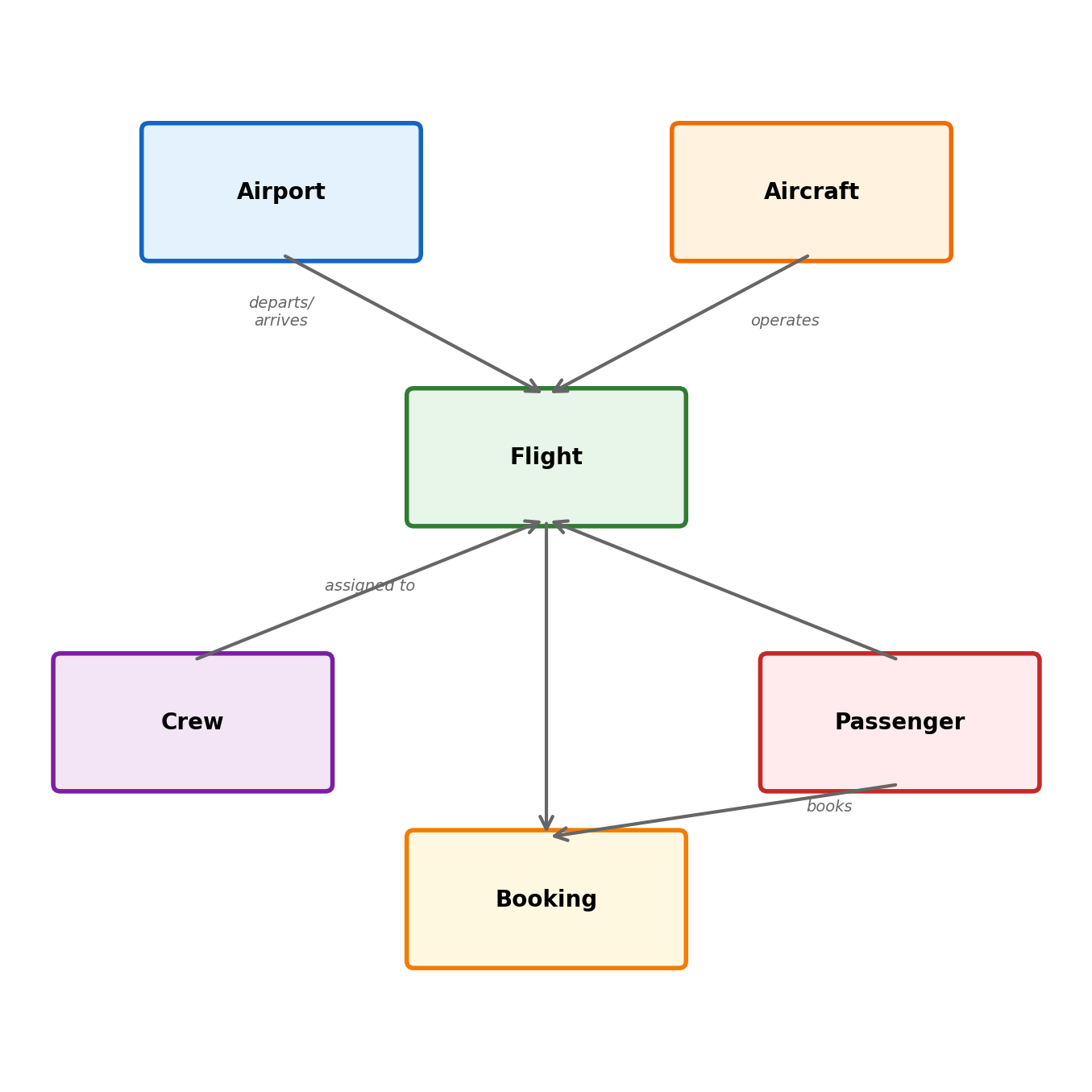

The Aviation Domain

An aviation domain: airlines, airports, flights, aircraft, crews, passengers, and bookings.

Core entities:

- Airports — code, name, city, timezone

- Aircraft — registration, model, seat capacity, range

- Flights — number, origin, destination, departure, arrival, aircraft assignment

- Crew members — employee ID, name, certifications

- Passengers — name, contact, frequent flyer status

- Bookings — passenger, flight, seat, fare class, status

Relationships:

- A flight departs from one airport, arrives at another

- A flight is operated by one aircraft

- A flight has multiple crew members (many-to-many)

- A booking connects a passenger to a flight

- An aircraft has a maintenance history

- Typed columns — timestamps, airport codes

- Constraints — a flight must reference existing airports

- Relationships — many-to-many crew assignments

- Concurrency — seat booking races

The Relational Model

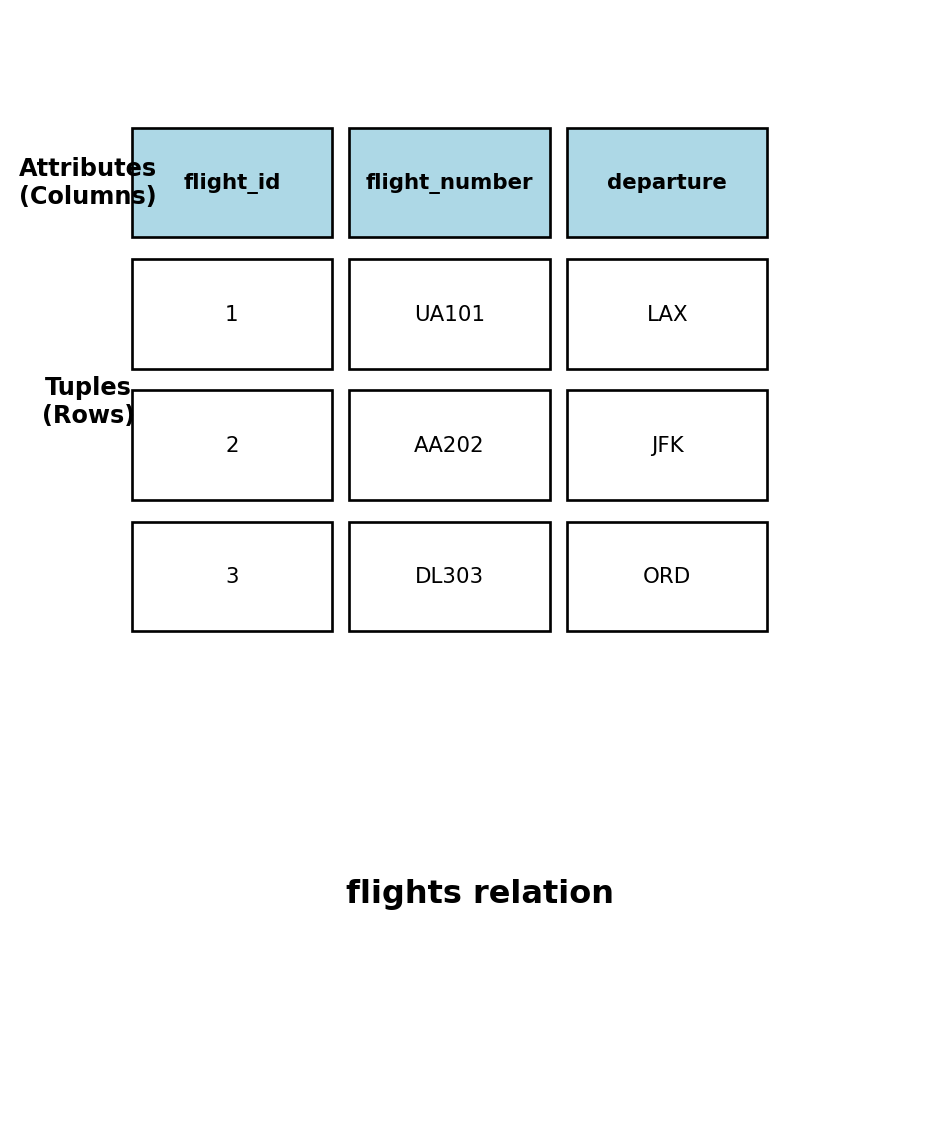

Data Organized into Tables

A relational database stores data in tables. Each table has a fixed set of columns with defined names and types. Each row is one record conforming to that structure.

| flight_id | flight_number | origin | destination | departure_time | seats_remaining |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AA 100 | LAX | JFK | 2026-02-12 08:00 | 23 |

| 2 | UA 512 | SFO | ORD | 2026-02-12 09:30 | 0 |

| 3 | DL 47 | ATL | LAX | 2026-02-12 11:15 | 84 |

This is not a spreadsheet. The structure is enforced:

- Every row has the same columns

- Every column has a declared type

- The database rejects data that violates the structure

- A row without a

flight_numberis not allowed (NOT NULL) - A

departure_timevalue of"next Thursday"is rejected — the column expects a timestamp

Types Restrict What Values a Column Can Hold

Column types are not annotations — they are enforced constraints. The database rejects operations that violate them.

Common types:

- INTEGER — whole numbers (flight_id, seat count)

- TEXT / VARCHAR(n) — character strings, optionally length-limited

- CHAR(n) — fixed-length strings (airport codes:

CHAR(3)) - TIMESTAMP — date and time with timezone

- BOOLEAN — true or false

- NUMERIC(p, s) — exact decimal with defined precision (monetary values, coordinates)

- UUID — 128-bit universally unique identifier

Type choice has consequences:

NUMERIC(10,2)for currency — floating-point arithmetic introduces rounding errors that are unacceptable for financial calculationsTIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONEfor departure times — a flight departing LAX at 08:00 Pacific is not the same instant as 08:00 EasternCHAR(3)for airport codes — fixed length enforces the IATA standard

What the database rejects:

-- Type mismatch: text in an integer column

INSERT INTO flights (seats_total) VALUES ('many');

-- ERROR: invalid input syntax for type integer

-- Constraint violation: string too long for CHAR(3)

INSERT INTO flights (origin) VALUES ('Los Angeles');

-- ERROR: value too long for type character(3)

-- Precision overflow

INSERT INTO fares (price) VALUES (999999999.99);

-- ERROR: numeric field overflowThe database enforces these at write time, not read time. Invalid data never enters the table. Every application that queries this table can rely on seats_total being an integer and origin being exactly 3 characters.

Contrast with JSON in a file: any value can appear in any field, and validation is the caller’s responsibility.

Every Row Needs an Identity

A table with duplicate rows is ambiguous. Which row should be updated? Which row was deleted? Without identity, operations on individual records are undefined.

Primary keys provide identity.

A primary key is a column (or combination of columns) whose value uniquely identifies each row. The database enforces two rules:

- Uniqueness — no two rows can have the same primary key value

- NOT NULL — the primary key cannot be absent

CREATE TABLE airports (

airport_code CHAR(3) PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT NOT NULL,

city TEXT NOT NULL,

timezone TEXT NOT NULL

);airport_code uniquely identifies each airport. Inserting a second row with 'LAX' is rejected. Inserting a row with no airport code is rejected.

Natural keys vs surrogate keys

A natural key uses data that already has meaning:

- Airport code (

LAX,JFK) — stable, universally understood - ISBN for books — assigned by external authority

A surrogate key is generated by the database:

- Auto-incrementing integer (

1, 2, 3, ...) - UUID (

550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000)

Trade-offs:

- Natural keys carry meaning but can change (airline mergers, code reassignments)

- Surrogates are stable and compact but carry no meaning —

flight_id = 7tells you nothing about the flight - Composite natural keys (multi-column) complicate joins

- Most systems use surrogates for internal identity and natural keys as unique constraints

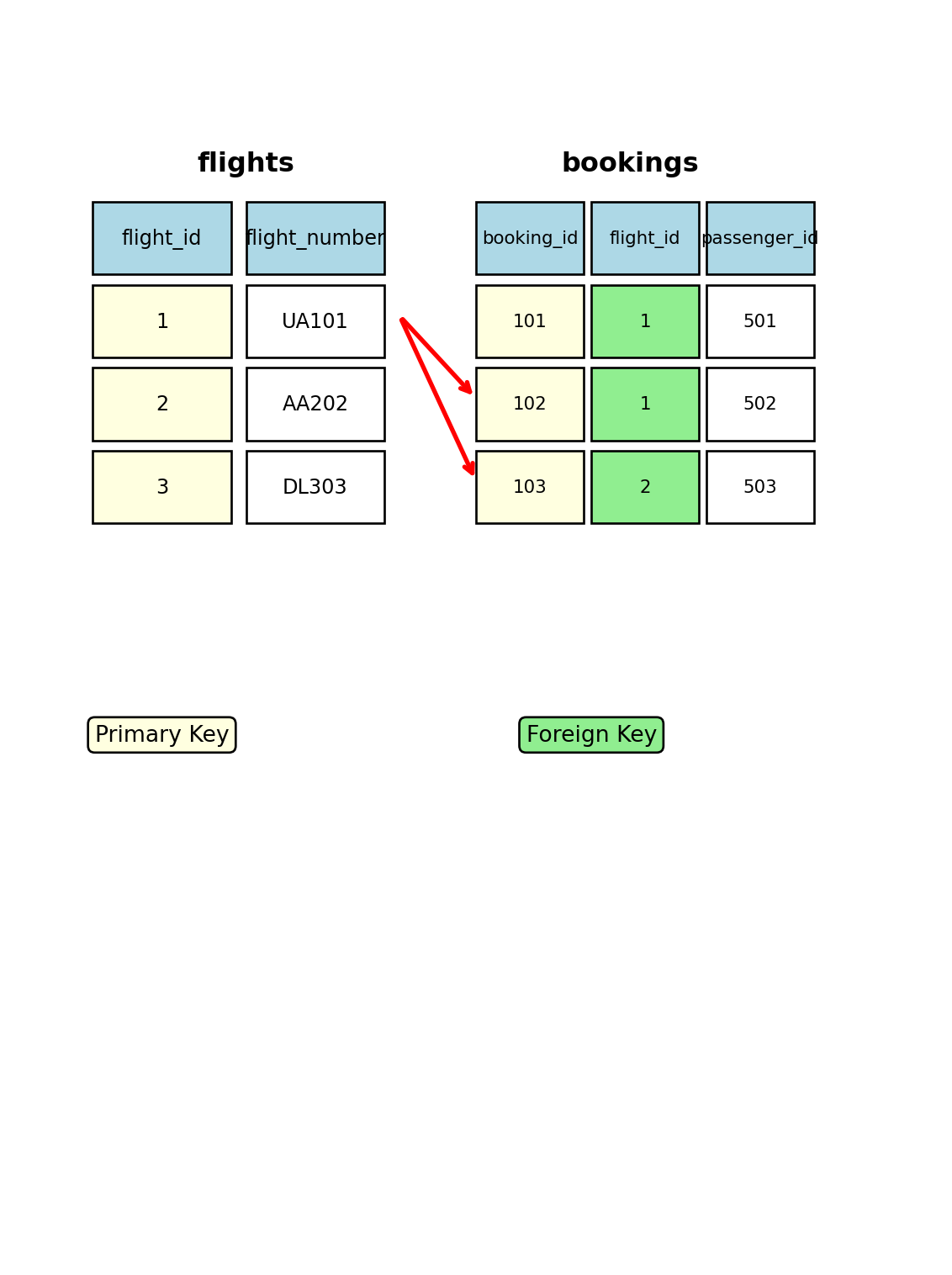

Foreign Keys Enforce Relationships Between Tables

Data about different entities lives in different tables. A flight has an origin airport and a destination airport. Rather than duplicating the airport name, city, and timezone in every flight row, the flight table references the airports table.

CREATE TABLE flights (

flight_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

flight_number TEXT NOT NULL,

origin CHAR(3) NOT NULL REFERENCES airports(airport_code),

destination CHAR(3) NOT NULL REFERENCES airports(airport_code),

departure_time TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE NOT NULL,

aircraft_id INTEGER REFERENCES aircraft(aircraft_id),

seats_remaining INTEGER NOT NULL

);What REFERENCES enforces:

originmust contain a value that exists inairports.airport_code- Inserting a flight with

origin = 'XYZ'fails if no airportXYZexists - This is referential integrity — the database guarantees that every reference points to a real record

Attempting to insert an invalid reference:

What happens when the referenced row is deleted:

An airport is decommissioned. Flights still reference it. The database has three options, specified when the foreign key is created:

- RESTRICT (default) — block the delete. Cannot remove an airport that flights reference.

- CASCADE — delete the airport and all flights that reference it

- SET NULL — delete the airport, set

originto NULL in referencing flights

Each represents a different business rule:

- RESTRICT: airports cannot be removed while flights exist (most common)

- CASCADE: removing an airport removes its flights (dangerous but appropriate in some contexts)

- SET NULL: flights become “orphaned” with unknown origin (rarely desirable)

References Eliminate Redundant Data

Without foreign keys: data duplicated in every row

| flight | origin_code | origin_name | origin_city | origin_tz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA 100 | LAX | Los Angeles International | Los Angeles | America/Los_Angeles |

| UA 200 | LAX | Los Angeles International | Los Angeles | America/Los_Angeles |

| DL 300 | LAX | Los Angeles International | Los Angeles | America/Los_Angeles |

The airport name, city, and timezone are repeated for every flight from LAX. If LAX changes its name (it was renamed in 2017), every flight row must be updated. Miss one and the data is inconsistent.

With 10,000 flights from LAX, the name "Los Angeles International" is stored 10,000 times.

With foreign keys: stored once, referenced by code

airports:

| airport_code | name | city | timezone |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAX | Los Angeles International | Los Angeles | America/Los_Angeles |

flights:

| flight_number | origin | destination |

|---|---|---|

| AA 100 | LAX | JFK |

| UA 200 | LAX | ORD |

| DL 300 | LAX | ATL |

Airport name stored once. Flights reference it by code. Name change: update one row in the airports table. All flights reflect the change immediately.

This principle — each fact stored once — is the foundation of normalization, developed in detail later.

Constraints Express Business Rules in the Schema

Beyond keys and types, the database can enforce arbitrary conditions on data.

NOT NULL — a value must be provided

A flight without a flight number cannot exist. The database rejects the insert rather than storing an incomplete record.

UNIQUE — no duplicates allowed

No two aircraft can share a registration number. Unlike a primary key, a UNIQUE column can be NULL (an aircraft awaiting registration).

DEFAULT — value when none is provided

A new booking without an explicit status is automatically 'confirmed'.

CHECK — arbitrary conditions

The seat count cannot go negative. The database rejects any update that would set seats_remaining to -1. This prevents overselling at the storage layer, regardless of application logic.

A flight cannot arrive before it departs. This catches data entry errors, application bugs, and timezone conversion mistakes before they become corrupt records.

These rules are enforced regardless of which application writes the data. The booking web application, the crew scheduling system, and the batch data loader all face the same constraints. No application can bypass them.

Constraints as Centralized Enforcement

Consider the alternative: every application validates independently.

- The web application checks

seats_remaining >= 0before confirming a booking - The batch import tool checks

seats_remaining >= 0before loading flight data - The admin console checks

seats_remaining >= 0before manual adjustments - A new mobile API is added six months later. The developer doesn’t know about the constraint. Negative seat counts enter the database.

Three applications enforced the rule correctly. The fourth didn’t. The data is now corrupt, and the source of the corruption is difficult to trace.

With a CHECK constraint on the column, the fourth application’s bad write is rejected at the database level. The rule is defined once, in the schema, and enforced universally.

NULL Represents Missing or Unknown Data

NULL is not zero. NULL is not an empty string. NULL is not false. NULL means the value is not known or does not apply.

When NULL is appropriate:

CREATE TABLE flights (

...

actual_departure TIMESTAMP, -- NULL until takeoff

gate_number TEXT, -- NULL if not assigned

delay_minutes INTEGER -- NULL if on time

);A flight that hasn’t departed yet has no actual_departure. The value is genuinely unknown — not zero, not “1970-01-01”, not a placeholder. NULL is the correct representation.

When NULL is not appropriate:

flight_number TEXT NOT NULL -- every flight has a number

origin CHAR(3) NOT NULL -- every flight has an originNOT NULL constraints prohibit NULL where absence would be nonsensical. A flight without an origin is not a flight.

NULL in expressions:

Any arithmetic or comparison with NULL yields NULL:

This is three-valued logic: TRUE, FALSE, NULL. Most languages have two truth values. SQL has three. This causes real bugs:

-- This finds NO rows where gate_number is NULL

SELECT * FROM flights WHERE gate_number = NULL;

-- This is correct

SELECT * FROM flights WHERE gate_number IS NULL;The first query compares each row’s gate_number with NULL. The comparison yields NULL, which is not TRUE, so no rows match — even the rows where gate_number is actually NULL.

NULL Propagation Affects Aggregation and Logic

Aggregation with NULLs:

-- delay_minutes: [10, NULL, 30, NULL, 20]

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM flights; -- 5

SELECT COUNT(delay_minutes) FROM flights; -- 3

SELECT AVG(delay_minutes) FROM flights; -- 20.0COUNT(*)counts rows — 5 rows existCOUNT(delay_minutes)counts non-NULL values — 3 values existAVG(delay_minutes)averages non-NULL values — (10 + 30 + 20) / 3 = 20.0, not (10 + 0 + 30 + 0 + 20) / 5

COUNT(*) and COUNT(column) return different numbers on the same data. Treating NULL as zero in averages silently changes the result.

Logical operations:

FALSE AND NULL is FALSE because regardless of the unknown value, the result is FALSE. TRUE OR NULL is TRUE for the same reason. But TRUE AND NULL is NULL — the result depends on the unknown value.

The Relational Model in One Table Definition

Putting it together — a CREATE TABLE statement that exercises types, primary key, foreign keys, and constraints:

CREATE TABLE bookings (

booking_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

passenger_id INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES passengers(passenger_id),

flight_id INTEGER NOT NULL REFERENCES flights(flight_id),

seat_number TEXT,

fare_class CHAR(1) NOT NULL CHECK (fare_class IN ('F', 'J', 'W', 'Y')),

booking_time TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE NOT NULL DEFAULT now(),

status TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'confirmed'

CHECK (status IN ('confirmed', 'cancelled', 'checked_in', 'boarded')),

UNIQUE (flight_id, seat_number)

);Identity and references:

booking_id— surrogate key, auto-generatedpassenger_id— must reference an existing passengerflight_id— must reference an existing flight- Neither reference can be NULL — a booking without a passenger or flight is meaningless

Constraints as business rules:

fare_classis one of F (first), J (business), W (premium economy), Y (economy) — no other values acceptedstatusfollows a defined lifecycle — no arbitrary strings(flight_id, seat_number)is UNIQUE — two passengers cannot occupy the same seat on the same flightseat_numbercan be NULL — seat assigned laterbooking_timedefaults to the current timestamp

The Aviation Schema

Four tables, connected by foreign keys. This is the working schema for the rest of the lecture.

Foreign key connections:

flights.origin→airports.airport_codeflights.destination→airports.airport_codeflights.aircraft_id→aircraft.aircraft_idbookings.flight_id→flights.flight_idbookings.passenger_id→passengers.passenger_id(table added later)

What the schema enforces:

- Flights cannot reference nonexistent airports or aircraft

- Bookings cannot reference nonexistent flights

- Seat counts cannot go negative

- Fare classes restricted to valid codes (F/J/W/Y)

- No duplicate seat assignments per flight

SQL

SQL Describes What, Not How

SQL is a declarative language. A query specifies the result — which rows, which columns, what conditions — and the database determines how to produce it.

SELECT flight_number, origin, departure_time

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LAX'

AND departure_time > '2026-02-12'

ORDER BY departure_time;What the query specifies:

- Three columns from the

flightstable - Only rows where origin is LAX

- Only future departures

- Sorted by departure time

What the query does not specify:

- Whether to use an index or scan the full table

- In what order to evaluate the conditions

- How to sort (in-memory, on-disk, using an index)

- How much memory to allocate

The database’s query optimizer makes these decisions based on table size, available indexes, and data distribution.

SELECT, FROM, WHERE

The core query pattern. Most SQL reads follow this structure.

SELECT flight_number, origin, destination, seats_remaining

FROM flights

WHERE seats_remaining > 0

AND departure_time BETWEEN '2026-02-12' AND '2026-02-13';SELECT — which columns to return

SELECT * -- all columns

SELECT flight_number -- one column

SELECT flight_number, origin -- multiple columns

SELECT DISTINCT origin -- unique values onlyFROM — which table (or tables) to read

WHERE — which rows to include

WHERE origin = 'LAX'

WHERE seats_remaining > 0

WHERE origin = 'LAX' AND destination = 'JFK'

WHERE origin IN ('LAX', 'SFO', 'SEA')

WHERE departure_time BETWEEN '2026-02-12' AND '2026-02-13'

WHERE flight_number LIKE 'AA%' -- starts with AA

WHERE gate_number IS NULL -- no gate assigned

WHERE gate_number IS NOT NULL -- gate assignedEach condition is a predicate. Predicates combine with AND, OR, and NOT. The database evaluates them against each row and returns those where the overall expression is TRUE.

SQL Execution Order Differs from Written Order

A query is written SELECT ... FROM ... WHERE ... GROUP BY ... ORDER BY, but the database evaluates clauses in a different order.

Why this matters:

- Column alias defined in SELECT cannot be used in WHERE — SELECT hasn’t executed yet

- HAVING can filter on aggregates, WHERE cannot — WHERE executes before GROUP BY

- ORDER BY can use SELECT aliases — it runs after SELECT

Sorting and Limiting Results

SELECT flight_number, departure_time, seats_remaining

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LAX'

AND seats_remaining > 0

ORDER BY departure_time ASC

LIMIT 10;ORDER BY — sort the result set

ORDER BY departure_time -- ascending (default)

ORDER BY departure_time ASC -- explicit ascending

ORDER BY departure_time DESC -- descending

ORDER BY origin, departure_time -- sort by origin first,

-- then by time within originWithout ORDER BY, the database returns rows in whatever order is cheapest to produce. That order is not guaranteed and may change between executions.

LIMIT — restrict result count

LIMIT without ORDER BY returns an arbitrary subset — which 10 rows is undefined.

Combining them:

“The next 5 flights departing LAX” requires both:

Writing Data: INSERT

Adding rows to a table.

INSERT INTO airports (airport_code, name, city, timezone)

VALUES ('LAX', 'Los Angeles International', 'Los Angeles', 'America/Los_Angeles');Column list is explicit — specifies which columns receive values, in what order. Columns with DEFAULT or NULL can be omitted.

-- booking_id is SERIAL (auto-generated)

-- booking_time has DEFAULT now()

INSERT INTO bookings (passenger_id, flight_id, fare_class)

VALUES (42, 7, 'Y');booking_id— auto-generated (SERIAL)booking_time— filled by DEFAULT (now())seat_number— set to NULL (no value provided)

Multi-row insert:

INSERT INTO airports (airport_code, name, city, timezone)

VALUES

('JFK', 'John F. Kennedy', 'New York', 'America/New_York'),

('ORD', 'O''Hare', 'Chicago', 'America/Chicago'),

('ATL', 'Hartsfield-Jackson', 'Atlanta', 'America/New_York');Constraint enforcement at insert time:

-- Foreign key violation

INSERT INTO flights (origin) VALUES ('ZZZ');

-- ERROR: Key (origin)=(ZZZ) is not present in "airports"

-- Unique violation

INSERT INTO airports (airport_code, ...) VALUES ('LAX', ...);

-- ERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraintConstraints are checked before the row enters the table.

Writing Data: UPDATE and DELETE

Modifying or removing existing rows.

UPDATE — change column values in rows matching a condition

-- Reassign all flights from decommissioned aircraft

UPDATE flights

SET aircraft_id = 501

WHERE aircraft_id = 299;Constraints apply to the new values. Setting seats_remaining to -1 is rejected if a CHECK constraint prohibits it.

DELETE — remove rows matching a condition

Foreign keys affect what can be deleted. Deleting an airport that flights reference is blocked (RESTRICT) unless the foreign key specifies CASCADE.

UPDATE and DELETE without WHERE:

These affect all rows in the table. No confirmation prompt, no undo. The WHERE clause is the only safeguard.

Data Lives in Separate Tables

Each table holds one kind of entity. Relationships are expressed through foreign keys — IDs and codes that reference rows in other tables.

A single booking row:

booking_id: 1001

passenger_id: 42

flight_id: 7

seat_number: 14A

fare_class: Y

status: confirmedPresent: the booking exists, which passenger, which flight, which seat.

Absent: passenger name, flight number, origin, destination, departure time — all in other tables.

To answer “passenger 42’s itinerary with flight details and airport names” requires combining four tables: bookings, flights, and airports (twice — origin and destination).

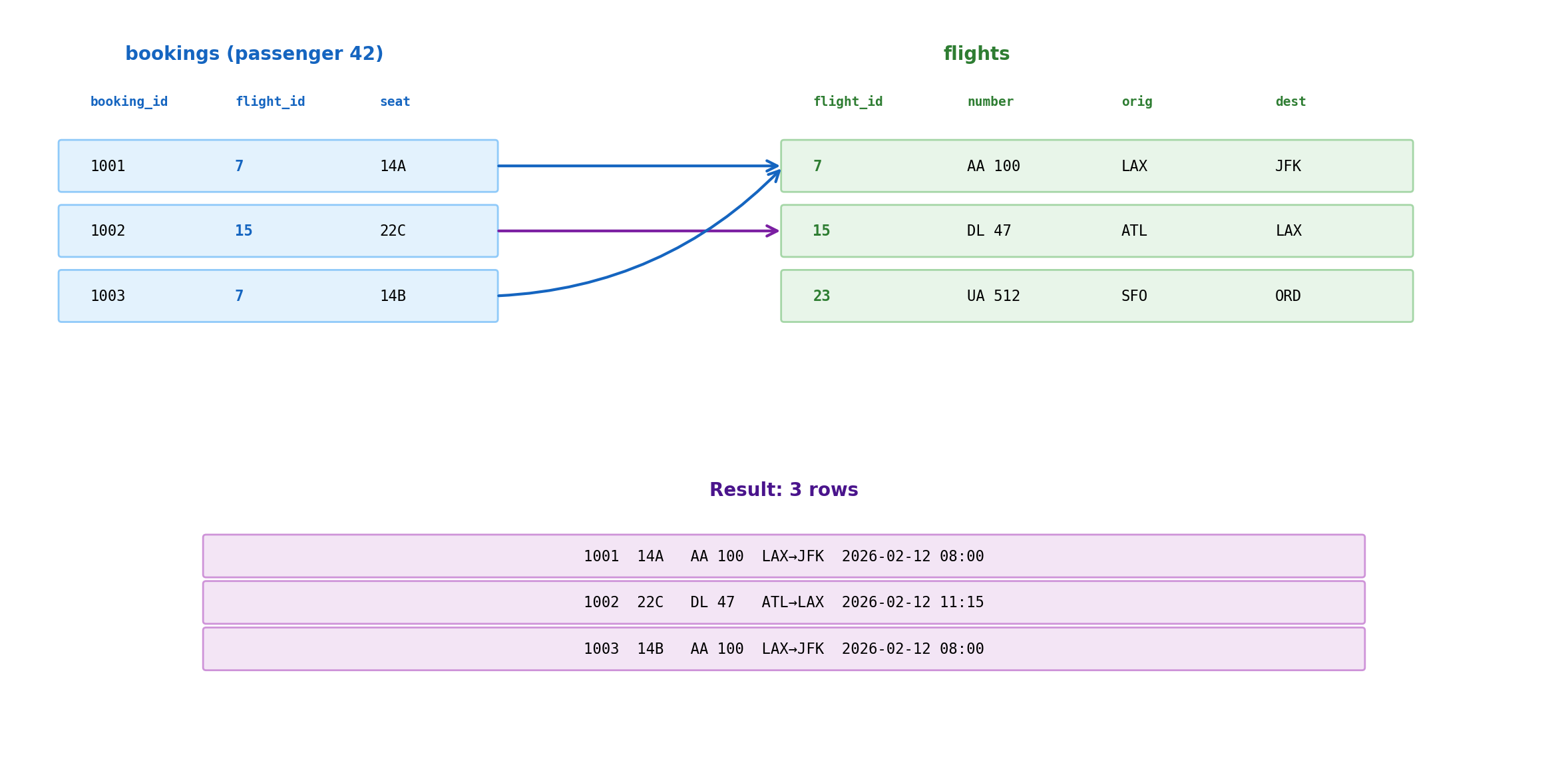

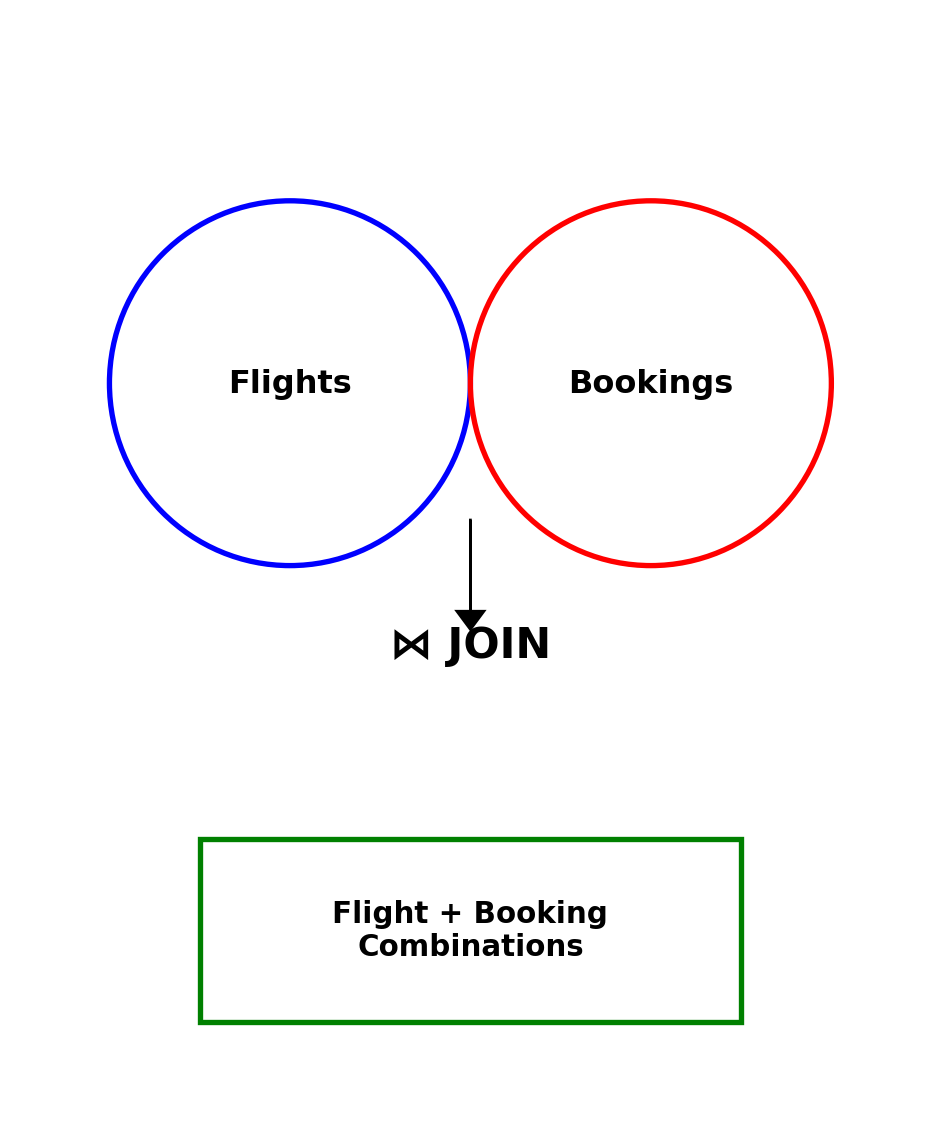

JOIN Matches Rows Across Tables

A JOIN combines rows from two tables based on a matching condition. For each row in the first table, the database finds rows in the second table where the condition holds, and produces a combined output row.

SELECT b.booking_id, b.seat_number, f.flight_number, f.departure_time

FROM bookings b

JOIN flights f ON b.flight_id = f.flight_id

WHERE b.passenger_id = 42;FROM bookings b— start with booking rows for passenger 42JOIN flights f— for each booking, find the flight whereflight_idmatchesON b.flight_id = f.flight_id— the match condition (foreign key = primary key)- Result: one row per booking, with flight details attached

- Bookings 1001 and 1003 both match flight 7 — two passengers on the same flight, two result rows

- Flight 23 has no bookings from passenger 42 — excluded from the result

- One-to-many: one flight, many bookings. The join produces one output row per booking, not per flight

The JOIN Condition Controls Matching

The ON clause specifies how rows from the two tables relate — typically a foreign key in one table matching a primary key in the other.

Without a join condition — the cross product:

Every booking paired with every flight. 1,000 bookings × 10,000 flights = 10 million rows. Almost all meaningless.

The ON clause filters the cross product down to only meaningful pairs — rows where the foreign key actually matches.

ON as a filter on the cross product:

| bookings.flight_id | flights.flight_id | match? |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 7 | yes → include |

| 7 | 15 | no → discard |

| 7 | 23 | no → discard |

| 15 | 7 | no → discard |

| 15 | 15 | yes → include |

| 15 | 23 | no → discard |

6 possible pairs → 2 matches

In production, the optimizer never materializes the full cross product — it uses indexes and hash tables to find matches directly.

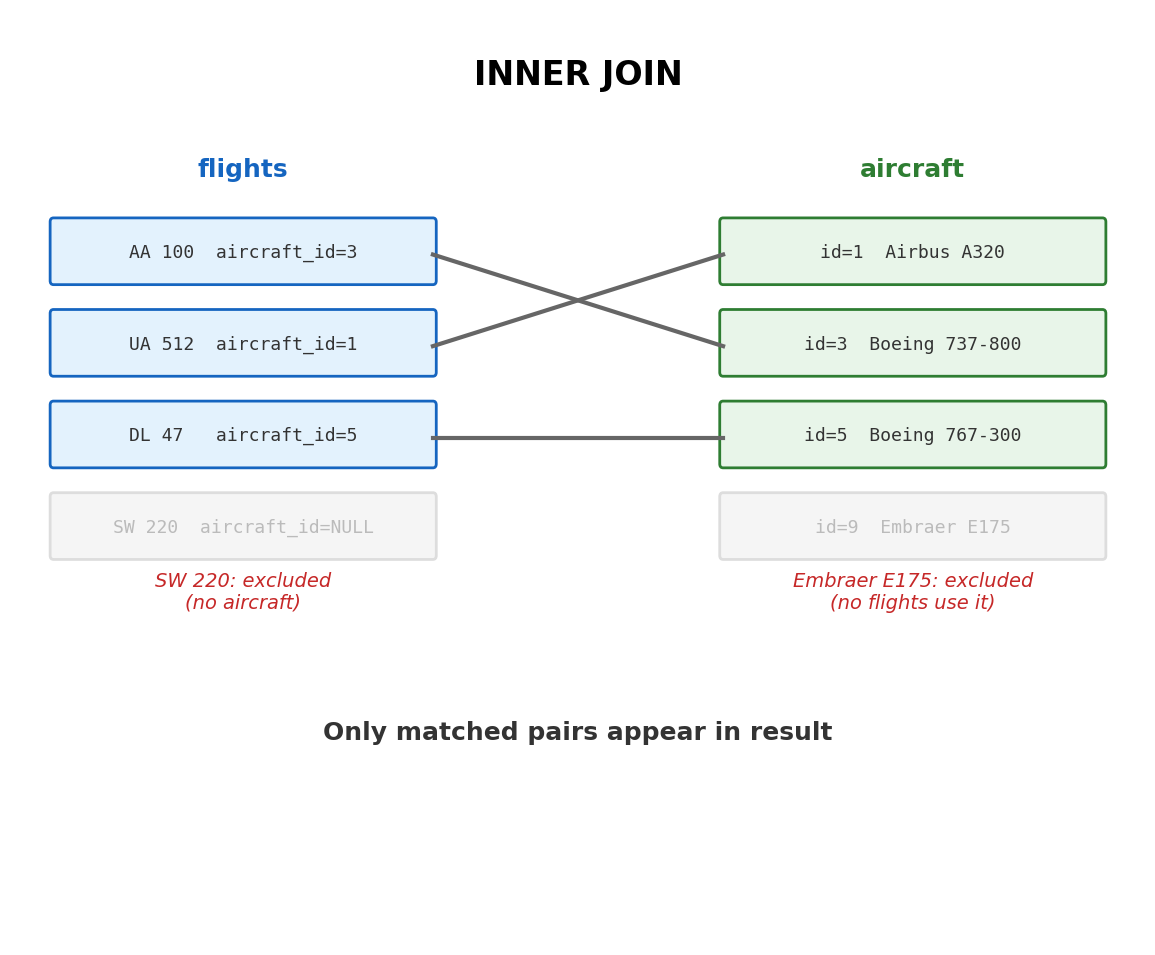

INNER JOIN Returns Only Matching Rows

The default JOIN (also written INNER JOIN) includes a row in the result only if a match exists in both tables.

SELECT f.flight_number, a.model AS aircraft

FROM flights f

JOIN aircraft a ON f.aircraft_id = a.aircraft_id;flight_number | aircraft

--------------+-----------------

AA 100 | Boeing 737-800

UA 512 | Airbus A320

DL 47 | Boeing 767-300500 flights, 20 have no aircraft assigned (aircraft_id is NULL). The result has 480 rows. The 20 unassigned flights are excluded — no match in the aircraft table.

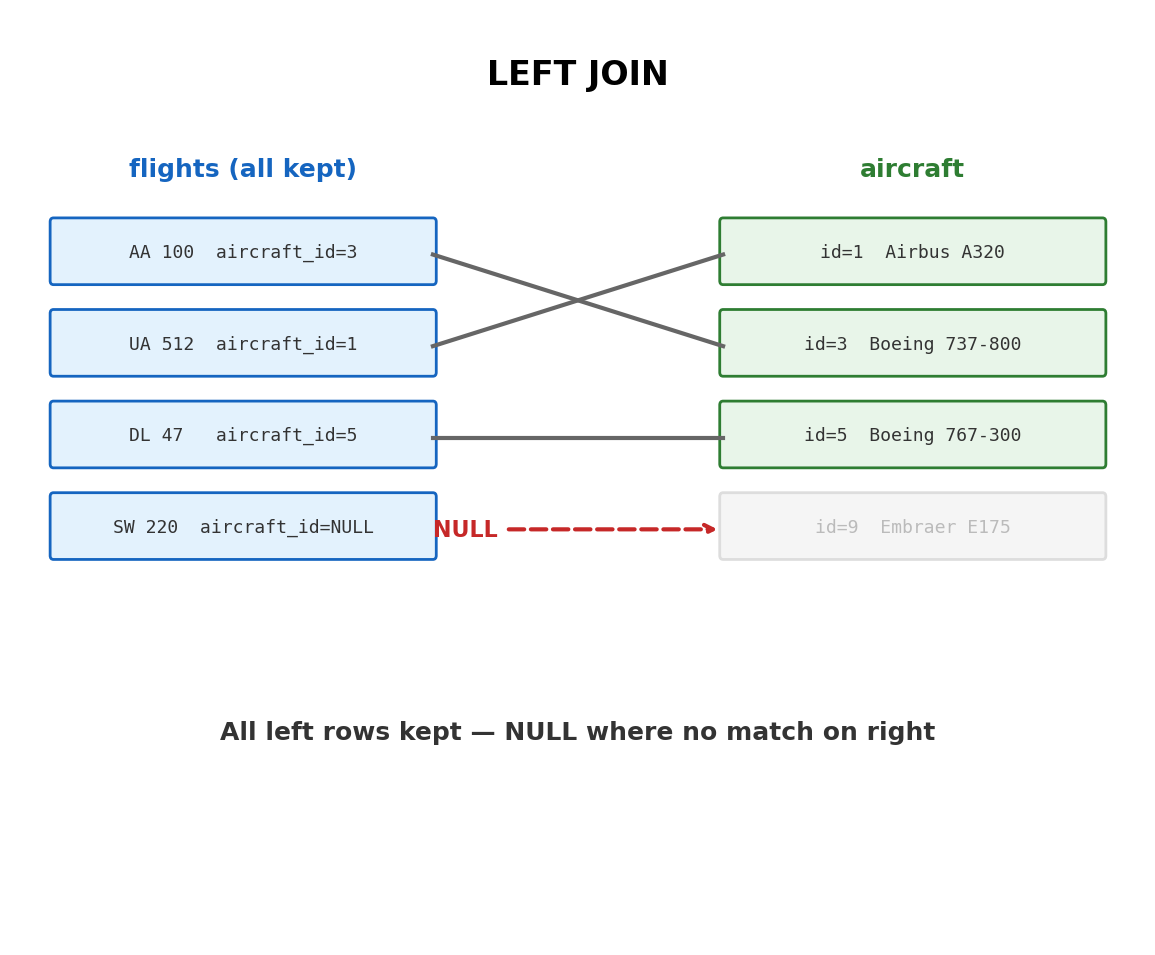

LEFT JOIN Preserves All Rows from the Left Table

LEFT JOIN returns every row from the left table. Where a match exists in the right table, the columns are filled. Where no match exists, the right-side columns are NULL.

SELECT f.flight_number, a.model AS aircraft

FROM flights f

LEFT JOIN aircraft a ON f.aircraft_id = a.aircraft_id;flight_number | aircraft

--------------+-----------------

AA 100 | Boeing 737-800

UA 512 | Airbus A320

DL 47 | Boeing 767-300

SW 220 | NULLAll 500 flights appear — including the 20 with no aircraft assignment. The aircraft column is NULL for those rows.

Joining Multiple Tables

Each JOIN adds one more table to the result, matching on its own condition. Chains of joins follow the foreign key relationships through the schema.

SELECT b.booking_id, b.fare_class, b.seat_number,

f.flight_number, f.departure_time,

a_orig.name AS origin_airport,

a_dest.name AS destination_airport

FROM bookings b

JOIN flights f ON b.flight_id = f.flight_id

JOIN airports a_orig ON f.origin = a_orig.airport_code

JOIN airports a_dest ON f.destination = a_dest.airport_code

WHERE b.passenger_id = 42;The join chain:

bookings— start with passenger 42’s bookings- →

flights— match each booking to its flight viaflight_id - →

airportsasa_orig— resolve origin code to airport name - →

airportsasa_dest— resolve destination code to airport name

The airports table appears twice with different aliases — a flight references two different airports. Aliases (a_orig, a_dest) disambiguate which role each join fills.

booking | fare | seat | flight | departure | origin | dest

--------+------+------+--------+------------------+------------------+-----------

1001 | Y | 14A | AA 100 | 2026-02-12 08:00 | Los Angeles Intl | John F. Kennedy

1002 | Y | 22C | DL 47 | 2026-02-12 11:15 | Hartsfield-Jksn | Los Angeles IntlEach result row assembles data from four tables:

booking_id,fare,seat— from bookingsflight,departure— from flightsorigin,dest— from airports (two separate joins)

Joins Reassemble Normalized Data

Each fact stored once — airport name in one row, flight details in one row — reassembled by joins at query time.

The cost of reassembly: CPU and I/O to match rows across tables. Indexes on join columns (foreign keys, primary keys) keep this cost proportional to result size, not table size.

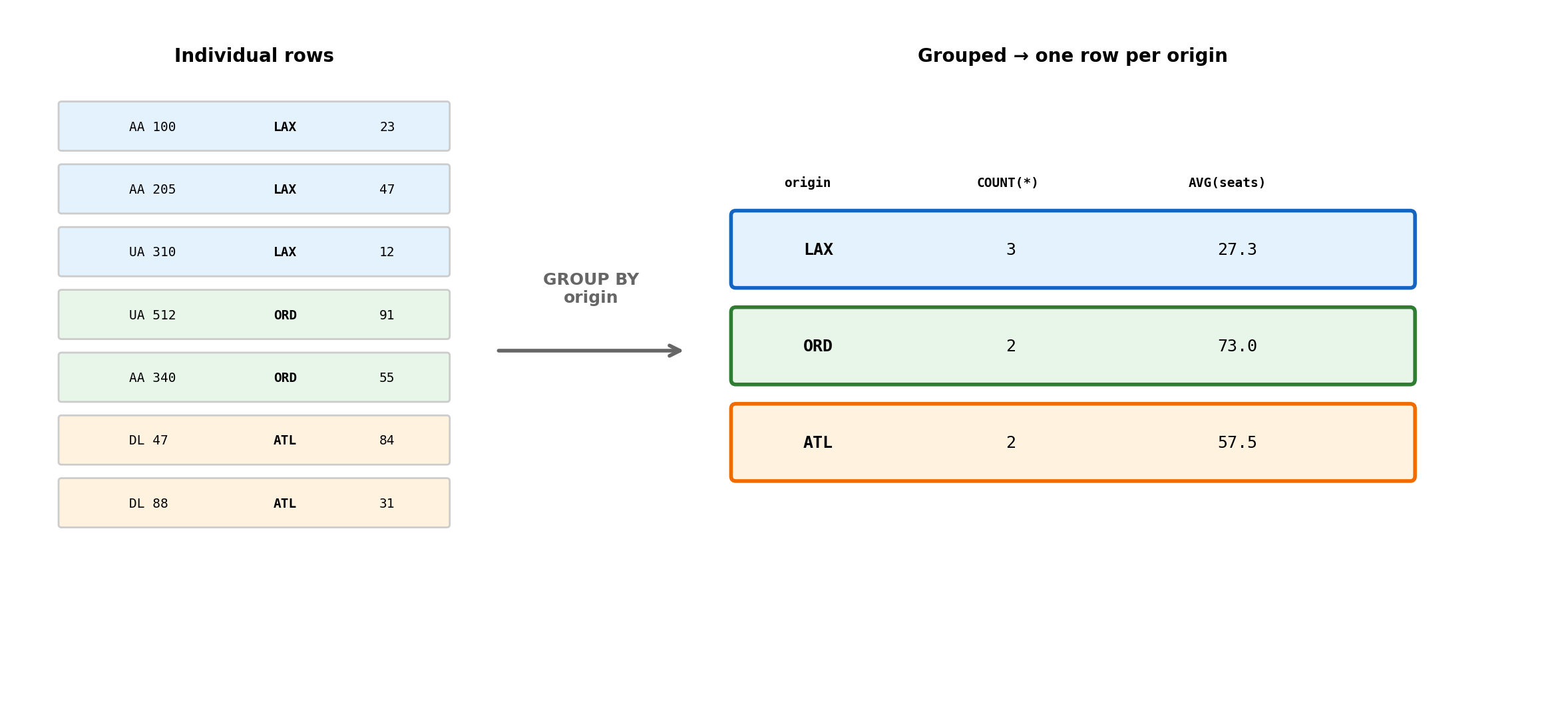

Aggregation: GROUP BY and Aggregate Functions

Aggregation computes summary values across sets of rows.

SELECT origin, COUNT(*) AS flight_count, AVG(seats_remaining) AS avg_seats

FROM flights

WHERE departure_time BETWEEN '2026-02-12' AND '2026-02-13'

GROUP BY origin

ORDER BY flight_count DESC;origin | flight_count | avg_seats

-------+--------------+----------

LAX | 47 | 34.2

ORD | 38 | 52.1

ATL | 35 | 28.7

JFK | 31 | 41.5Aggregate functions operate on sets of rows:

- **COUNT(*)** — number of rows

- COUNT(column) — number of non-NULL values

- SUM(column) — total

- AVG(column) — mean of non-NULL values

- MIN(column) / MAX(column) — extremes

Without GROUP BY, aggregates operate on the entire result set. With GROUP BY, they operate per-group.

WHERE vs HAVING:

WHERE filters individual rows before grouping. HAVING filters groups after aggregation.

SELECT origin, COUNT(*) AS flight_count

FROM flights

WHERE departure_time > '2026-02-12' -- filter rows

GROUP BY origin

HAVING COUNT(*) > 30; -- filter groups“Airports with more than 30 flights tomorrow” — WHERE selects tomorrow’s flights, GROUP BY groups by origin, HAVING keeps only groups with more than 30.

GROUP BY Partitions Rows, Then Collapses Them

7 rows → 3 summary rows. The detail is gone — only the aggregates remain. GROUP BY answers “how many” and “what’s the average” but discards individual row identity.

Aggregation Across Joins

Aggregation and joins combine to answer questions that span multiple tables.

Bookings per airline for a given date:

SELECT

substring(f.flight_number, 1, 2) AS airline,

COUNT(b.booking_id) AS total_bookings,

COUNT(DISTINCT f.flight_id) AS flights

FROM flights f

JOIN bookings b ON f.flight_id = b.flight_id

WHERE f.departure_time::date = '2026-02-12'

GROUP BY airline

ORDER BY total_bookings DESC;airline | total_bookings | flights

--------+----------------+--------

AA | 1247 | 23

UA | 983 | 18

DL | 871 | 21Execution order:

- FROM + JOIN — one row per booking-flight pair

- WHERE — keep only tomorrow’s flights

- GROUP BY — partition by airline prefix

- SELECT aggregates — count bookings and distinct flights per group

- ORDER BY — sort by total bookings

COUNT(b.booking_id) — counts every booking row in the group

COUNT(DISTINCT f.flight_id) — counts unique flights only

23 flights, 1,247 bookings → ~54 passengers per flight

Subqueries and CTEs

Complex questions often require composing queries — the result of one query becomes input to another.

Subquery — nested inside another query:

-- Flights with above-average bookings

SELECT f.flight_number, COUNT(b.booking_id) AS bookings

FROM flights f

JOIN bookings b ON f.flight_id = b.flight_id

GROUP BY f.flight_id, f.flight_number

HAVING COUNT(b.booking_id) > (

SELECT AVG(booking_count) FROM (

SELECT COUNT(*) AS booking_count

FROM bookings GROUP BY flight_id

) sub

);Reads inside-out:

- Innermost — count bookings per flight

- Middle — average those counts

- Outer — keep flights above average

CTE (Common Table Expression) — same logic, reads top-to-bottom:

WITH per_flight AS (

SELECT flight_id, COUNT(*) AS booking_count

FROM bookings

GROUP BY flight_id

),

avg_bookings AS (

SELECT AVG(booking_count) AS avg_count

FROM per_flight

)

SELECT f.flight_number, pf.booking_count

FROM per_flight pf

JOIN flights f ON pf.flight_id = f.flight_id

WHERE pf.booking_count > (SELECT avg_count FROM avg_bookings);- Each

WITHclause defines a named intermediate result - CTEs can reference earlier CTEs

- Main query uses them like tables

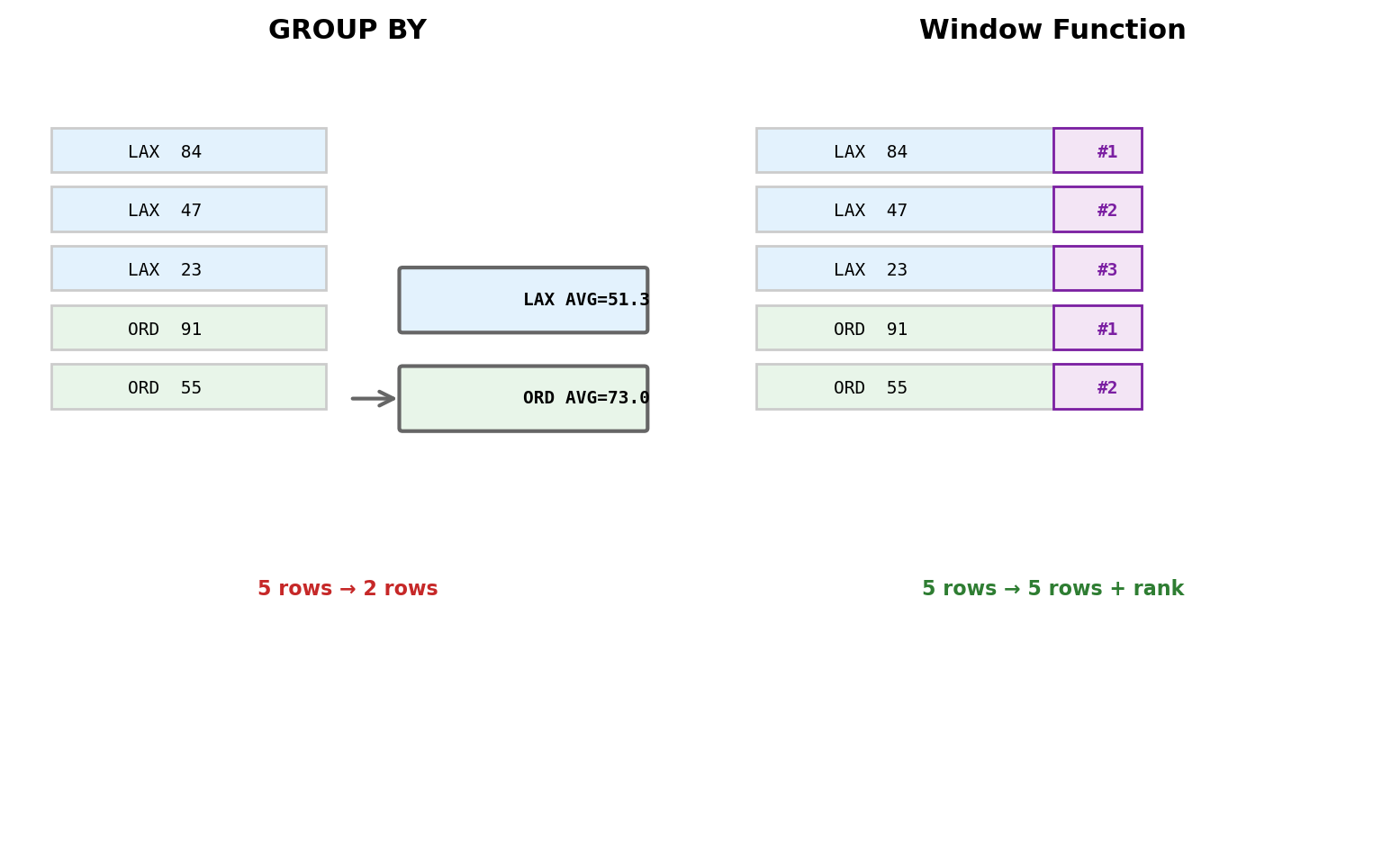

Window Functions

GROUP BY collapses rows — one output per group, detail discarded. Window functions compute across related rows while preserving every row in the result.

SELECT flight_number, origin, seats_remaining,

RANK() OVER (

PARTITION BY origin

ORDER BY seats_remaining DESC

) AS availability_rank

FROM flights

WHERE departure_time::date = '2026-02-12';flight_number | origin | seats | rank

--------------+--------+-------+-----

AA 100 | LAX | 84 | 1

UA 205 | LAX | 47 | 2

DL 300 | LAX | 23 | 3

UA 512 | ORD | 91 | 1

AA 340 | ORD | 55 | 2Every row is preserved. The rank is computed within each origin partition.

Common window functions:

- ROW_NUMBER() / RANK() / DENSE_RANK() — numbering and ranking

- SUM(…) OVER (…) — running totals

- LAG(col, n) / LEAD(col, n) — access previous/next row values

EXPLAIN: Seeing the Optimizer’s Plan

Every query gets an execution plan. EXPLAIN reveals what the optimizer chose.

EXPLAIN SELECT flight_number, departure_time

FROM flights

WHERE origin = 'LAX' AND departure_time > '2026-02-12';Without an index on origin:

Seq Scan on flights Filter: (origin = ‘LAX’ AND departure_time > …) Rows Removed by Filter: 9700 Actual Rows: 300

Sequential scan — reads every row, discards non-matches. Cost proportional to table size.

With an index on origin:

Index Scan using flights_origin_idx on flights Index Cond: (origin = ‘LAX’) Filter: (departure_time > …) Actual Rows: 300

Index scan — navigates directly to LAX flights, then filters by date. Reads hundreds of rows instead of tens of thousands.

Same SQL, different plans. The optimizer switched strategy because an index became available. No application code changed.

Common plan nodes:

- Seq Scan — full table read, O(n)

- Index Scan — index lookup, O(log n)

- Hash Join / Nested Loop — join strategies

- Sort — explicit sort (ORDER BY)

- Aggregate — GROUP BY computation

EXPLAIN ANALYZE — runs the query and reports actual times:

Planning Time: 0.2 ms Execution Time: 1.3 ms

Schema Design and ER Modeling

Querying vs Designing

SQL operates on existing tables. Someone decided those tables exist, chose the columns, defined the types, and drew the foreign key relationships.

Schema design is that prior step: given a domain (“airlines, flights, passengers, bookings”), decide:

- What entities need their own table

- What attributes each entity has

- How entities relate to each other

- What constraints enforce correctness

The aviation schema from section 02 was presented as given. This section develops the process that produces schemas like it.

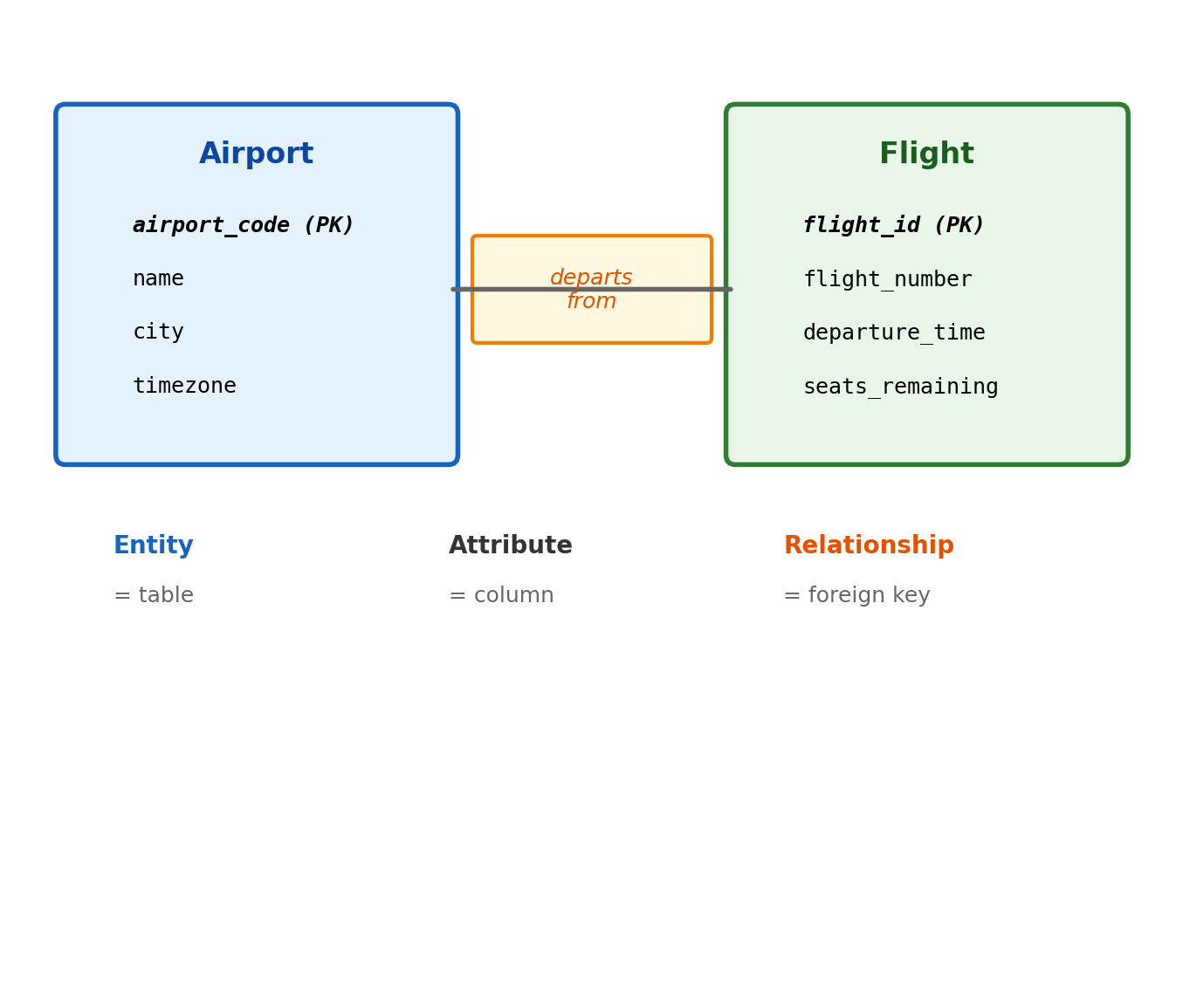

Entity-Relationship (ER) modeling is a design tool for this process.

- Visual notation for entities, attributes, and relationships

- Independent of any specific database — a design artifact, not SQL

- Forces decisions about cardinality (“can a flight have multiple aircraft?”) and participation (“must every aircraft be assigned to a flight?”) before writing DDL

- The ER diagram is a blueprint; the

CREATE TABLEstatements are the implementation

Entities, Attributes, Relationships

Entities — things with independent existence that the system needs to track.

- Airport, Aircraft, Flight, Crew Member, Passenger

- Each becomes a table

- Has a primary key that provides identity

Attributes — properties of an entity.

- Airport: code, name, city, timezone

- Aircraft: registration, model, seat capacity, range

- Each becomes a column with a type

Relationships — associations between entities.

- A flight departs from an airport

- A flight is operated by an aircraft

- A passenger books a flight

- Relationships are named — the verb matters for understanding direction and meaning

Cardinality: How Many on Each Side

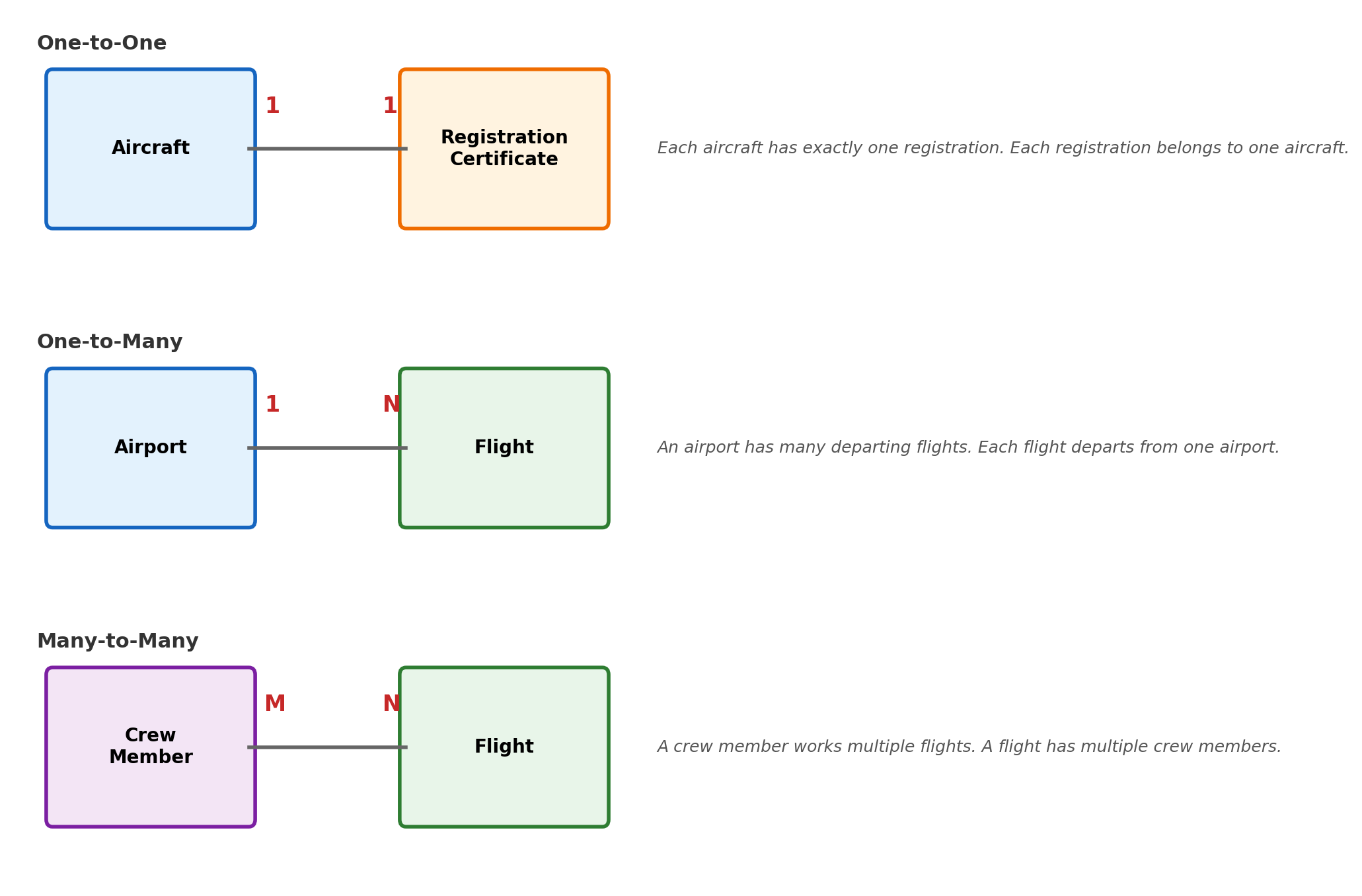

Cardinality specifies how many instances of one entity can be associated with instances of another. This determines how the relationship is implemented in tables.

Cardinality Determines Implementation

One-to-many → foreign key in the “many” table

An airport has many flights. The foreign key goes in flights:

The foreign key lives in flights (the “many” side). The airport table has no reference back — the relationship is navigated from the many side.

One-to-one → foreign key with UNIQUE

CREATE TABLE registration_certs (

cert_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

aircraft_id INTEGER UNIQUE

REFERENCES aircraft(aircraft_id),

...

);The UNIQUE constraint on aircraft_id enforces that no two certificates reference the same aircraft.

Many-to-many → junction table

Neither table can hold a single foreign key to the other — a crew member works multiple flights and a flight has multiple crew. A junction table represents the relationship:

CREATE TABLE crew_assignments (

crew_id INTEGER REFERENCES crew(crew_id),

flight_id INTEGER REFERENCES flights(flight_id),

role TEXT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (crew_id, flight_id)

);crew_id | flight_id | role

--------+-----------+---------

101 | 7 | captain

102 | 7 | first_officer

101 | 15 | captain

103 | 15 | first_officer- One row per crew-flight pair

- Composite primary key

(crew_id, flight_id)prevents duplicate assignments - Navigable in both directions: “who’s on flight 7?” and “what flights does crew 101 work?”

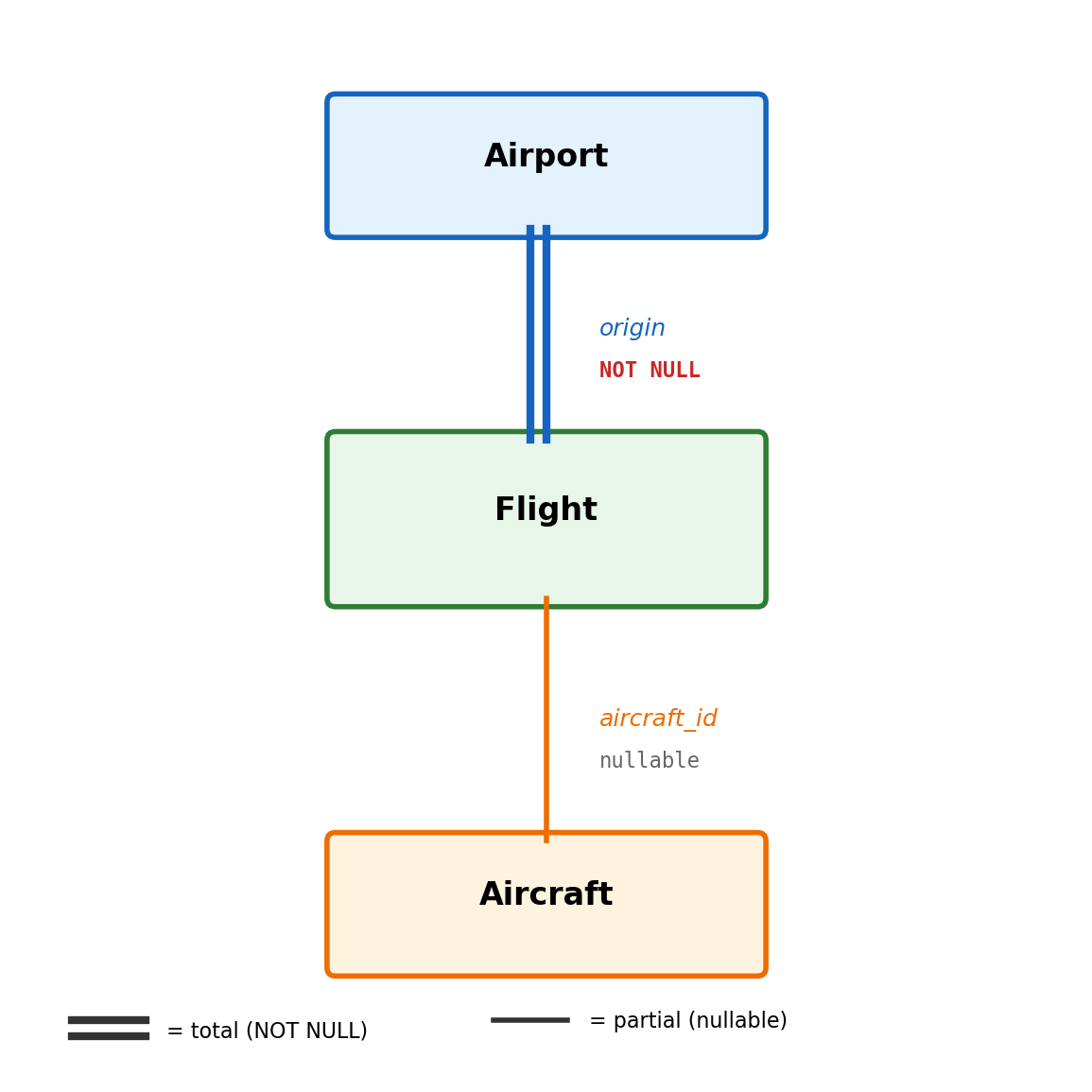

Participation: Must Every Entity Participate?

Total participation — every instance of the entity must participate in the relationship.

- Every flight must have an origin airport — a flight without an origin is nonsensical

- Implementation:

NOT NULLon the foreign key

Partial participation — participation is optional.

- An aircraft may or may not be assigned to a flight — new aircraft, or aircraft in maintenance

- Implementation: foreign key allows NULL

Total participation → NOT NULL on the foreign key. Partial participation → nullable foreign key. The ER diagram captures the business rule; the DDL enforces it.

Weak Entities Depend on a Parent for Identity

Most entities are identified by their own attributes — an airport by its code, an aircraft by its registration. Weak entities have meaning only within the context of a parent.

A flight leg — one segment of a multi-stop flight:

- Flight AA 100, Leg 1: LAX → DEN

- Flight AA 100, Leg 2: DEN → JFK

“Leg 1” alone is not unique — every multi-stop flight has a “leg 1.” The leg is only identifiable as leg 1 of flight AA 100.

CREATE TABLE flight_legs (

flight_id INTEGER REFERENCES flights(flight_id),

leg_number INTEGER,

origin CHAR(3) REFERENCES airports(airport_code),

destination CHAR(3) REFERENCES airports(airport_code),

departure_time TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE,

arrival_time TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE,

PRIMARY KEY (flight_id, leg_number)

);Composite primary key (flight_id, leg_number):

flight_id— identifies which flight (from parent)leg_number— identifies which leg within that flight (partial key)- Together: unique. Neither alone is sufficient.

Defining characteristics:

- Cannot exist without the parent — deleting the flight deletes its legs (CASCADE)

- Primary key includes parent’s key — identity depends on the parent

- Identifying relationship — the parent contributes to identity, not just association

Other examples: line items on an invoice, rooms within a building, episodes within a season.

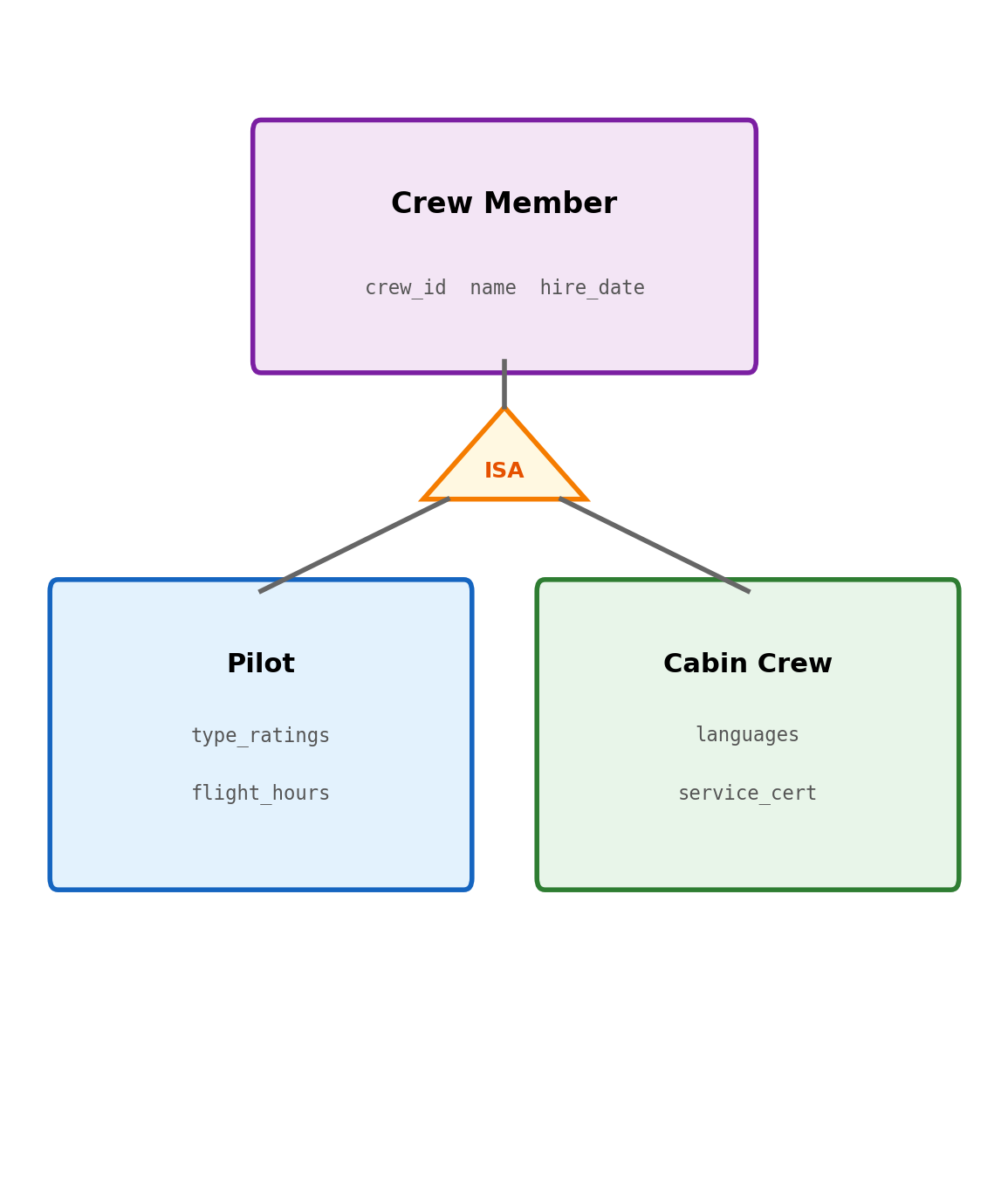

ISA Hierarchies: Specialization and Generalization

Some entities are subtypes of a more general entity. Crew members are all employees with shared attributes (name, employee ID, hire date), but pilots have type ratings and cabin crew have language certifications.

Implementation options:

Single table with type column:

CREATE TABLE crew (

crew_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT NOT NULL,

hire_date DATE NOT NULL,

crew_type TEXT NOT NULL CHECK (crew_type IN ('pilot', 'cabin')),

type_ratings TEXT[], -- NULL for cabin crew

flight_hours INTEGER, -- NULL for cabin crew

languages TEXT[], -- NULL for pilots

service_cert TEXT -- NULL for pilots

);- One table, simple queries, no joins

type_ratingsis NULL for every cabin crew row- Inapplicable columns accumulate as subtypes diverge

Separate tables, shared primary key:

CREATE TABLE crew (

crew_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT NOT NULL, hire_date DATE NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE pilots (

crew_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY REFERENCES crew(crew_id),

type_ratings TEXT[], flight_hours INTEGER

);

CREATE TABLE cabin_crew (

crew_id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY REFERENCES crew(crew_id),

languages TEXT[], service_cert TEXT

);- Each subtype holds only its own columns

- JOIN required for shared + specific attributes

- FK enforces subtype corresponds to real crew member

From Requirements to ER Diagram

Requirements (aviation booking system):

- Airlines operate flights between airports

- Each flight is operated by one aircraft

- Flights have scheduled departure and arrival times

- Crew members are assigned to flights; a flight has multiple crew

- Passengers book flights

- A booking records the passenger, flight, seat, and fare class

- Aircraft have maintenance records

Entities identified:

- Airport, Aircraft, Flight, Crew Member, Passenger, Booking, Maintenance Record

Relationships identified:

- Flight departs from / arrives at Airport (many-to-one, total)

- Flight operated by Aircraft (many-to-one, partial — aircraft may not be assigned yet)

- Crew Member assigned to Flight (many-to-many)

- Passenger makes Booking (one-to-many)

- Booking for Flight (many-to-one, total)

- Aircraft has Maintenance Record (one-to-many)

The Aviation ER Diagram

Cardinality summary:

- Airport 1 — N Flight (one airport, many flights)

- Aircraft 1 — N Flight (one aircraft, many flights)

- Crew M — N Flight (many-to-many)

- Passenger 1 — N Booking

- Booking N — 1 Flight (many bookings per flight)

- Aircraft 1 — N Maintenance

Implementation consequences:

- One-to-many: foreign key in the “many” table

- Many-to-many (Crew—Flight): junction table

crew_assignments - Booking is effectively a junction between Passenger and Flight, with additional attributes (seat, fare class, status)

- Maintenance is a weak entity — a maintenance record is identified by aircraft + date/sequence

Translating the ER Diagram to Tables

Each entity becomes a table. Relationships become foreign keys or junction tables. Cardinality and participation determine constraints.

Direct mapping rules:

- Entity → table

- Attribute → column with appropriate type

- Primary key → PRIMARY KEY constraint

- 1:N relationship → foreign key in the “many” table

- M:N relationship → junction table with composite key

- Total participation → NOT NULL on the foreign key

- Partial participation → nullable foreign key

- Weak entity → composite primary key including parent’s key

The aviation schema implements these rules:

-- Entity: Airport

CREATE TABLE airports (

airport_code CHAR(3) PRIMARY KEY, ...

);

-- Entity: Flight (1:N with Airport, total)

CREATE TABLE flights (

flight_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

origin CHAR(3) NOT NULL

REFERENCES airports(airport_code),

aircraft_id INTEGER -- partial: nullable

REFERENCES aircraft(aircraft_id),

...

);

-- M:N: Crew <-> Flight

CREATE TABLE crew_assignments (

crew_id INTEGER REFERENCES crew(crew_id),

flight_id INTEGER REFERENCES flights(flight_id),

role TEXT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (crew_id, flight_id)

);Design Decisions Have Downstream Consequences

The ER diagram forces decisions that affect every query, every constraint, and every future schema change.

“Can a booking exist without a flight?”

- If yes:

flight_idnullable, LEFT JOINs needed, application must handle orphaned bookings - If no:

NOT NULL REFERENCES, database prevents orphaned bookings at write time

“Can two passengers share a seat?”

- If no:

UNIQUE(flight_id, seat_number)— enforced by the database, regardless of application logic - If yes (standby, etc.): no unique constraint, application manages conflicts

“Is fare class a free-text field or an enumeration?”

- Free text: flexible, no validation, inconsistent values guaranteed over time (

"economy","Economy","Y","econ") - CHECK constraint:

fare_class IN ('F','J','W','Y')— consistent, but requires schema change to add a new class

These decisions are difficult to change later.

- Adding

NOT NULLto a column with existing NULLs → data migration - Splitting a table → rewrite every query that references it

- Changing a primary key → cascading changes to every foreign key

The cost of changing schema grows with the codebase that depends on it. Queries, application logic, indexes, migrations — all encode assumptions about table structure.

The ER diagram is where these decisions are made explicitly — before they are encoded in DDL and depended on by application code.

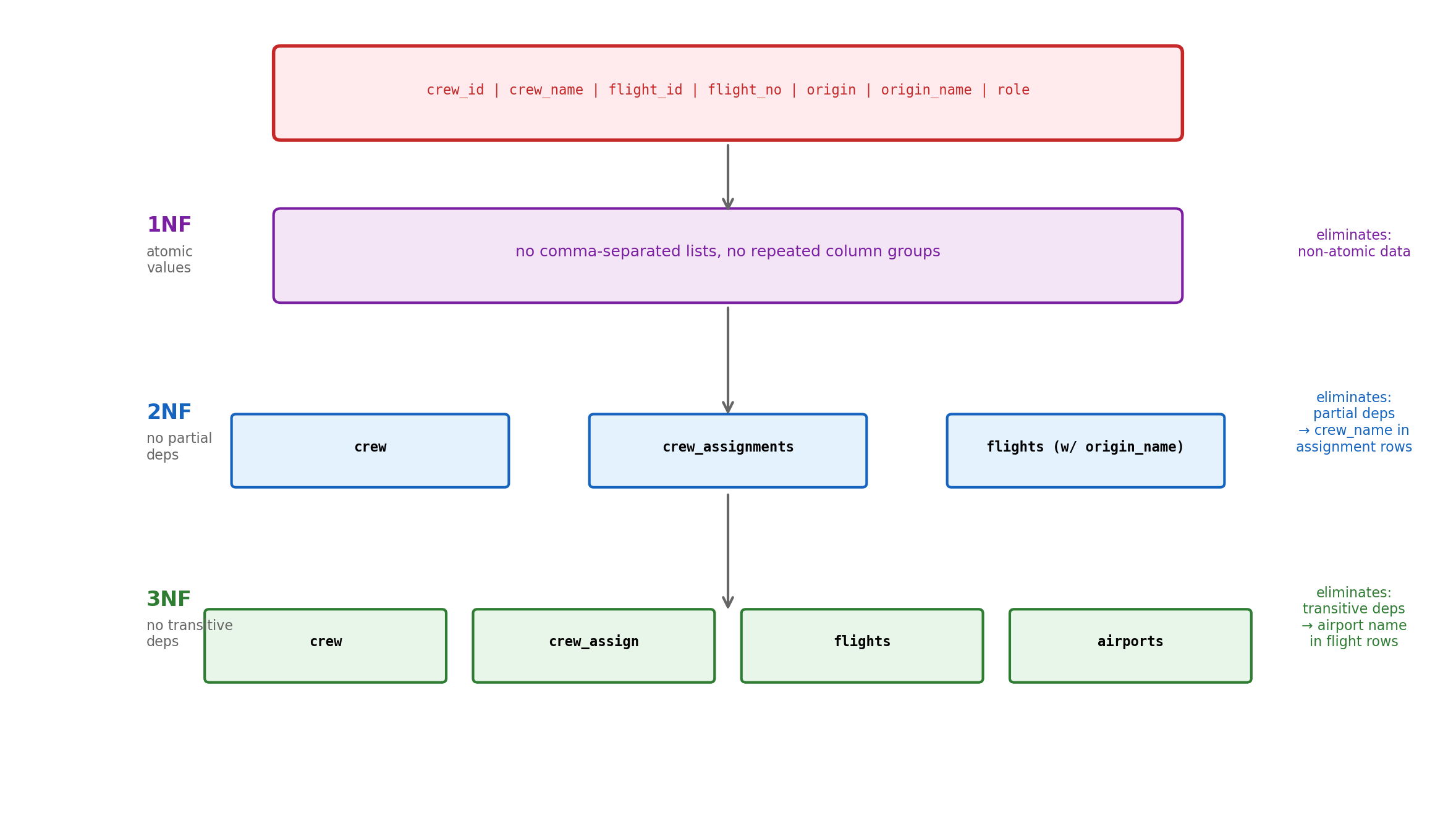

Normalization

Redundant Data Causes Anomalies

A single table tracking crew assignments with flight and airport details:

| crew_id | crew_name | flight_id | flight_number | origin | origin_name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | Chen | 7 | AA 100 | LAX | Los Angeles Intl |

| 102 | Okafor | 7 | AA 100 | LAX | Los Angeles Intl |

| 101 | Chen | 15 | DL 47 | ATL | Hartsfield-Jackson |

| 103 | Park | 15 | DL 47 | ATL | Hartsfield-Jackson |

The airport name "Los Angeles Intl" appears in every row for every crew member on every flight from LAX.

This is not just wasted storage. It creates three categories of anomaly:

- Update anomaly — LAX changes its name. Must update every row containing

LAX. Miss one → inconsistent data. - Insert anomaly — cannot record a new airport without a crew assignment to a flight from that airport.

- Delete anomaly — deleting the last crew assignment from ATL also deletes the fact that ATL is named “Hartsfield-Jackson.”

Anomalies in Practice

Update anomaly — partial update:

UPDATE crew_flights

SET origin_name = 'Los Angeles International'

WHERE origin = 'LAX';

-- Updates 2 of the 4 rows... application timeout

-- or WHERE clause was slightly wrongNow some rows say "Los Angeles Intl", others say "Los Angeles International". Same airport, two names. No constraint prevents this — no single source of truth.

Insert anomaly — forced coupling:

-- Want to add Denver International (DEN)

-- But the table requires crew_id and flight_id

INSERT INTO crew_flights (origin, origin_name)

VALUES ('DEN', 'Denver International');

-- ERROR: crew_id, flight_id cannot be NULLAn airport’s existence is coupled to a crew assignment existing — unrelated facts forced into one table.

Functional Dependencies

The formal basis for normalization. A functional dependency X → Y means: if two rows have the same value of X, they must have the same value of Y.

In the aviation domain:

airport_code → name, city, timezoneKnowing the airport code determines the name, city, and timezone. Two rows withLAXmust agree on"Los Angeles Intl".flight_id → flight_number, origin, destination, departure_timeA flight ID determines all the flight’s attributes.crew_id → crew_name, hire_dateA crew member’s ID determines their name and hire date.

Dependencies in the redundant table:

| crew_id | crew_name | flight_id | flight_number | origin | origin_name |

|---|

crew_id → crew_name(crew attribute)flight_id → flight_number, origin(flight attribute)origin → origin_name(airport attribute)

Three different entities mixed into one table, each with its own set of dependencies.

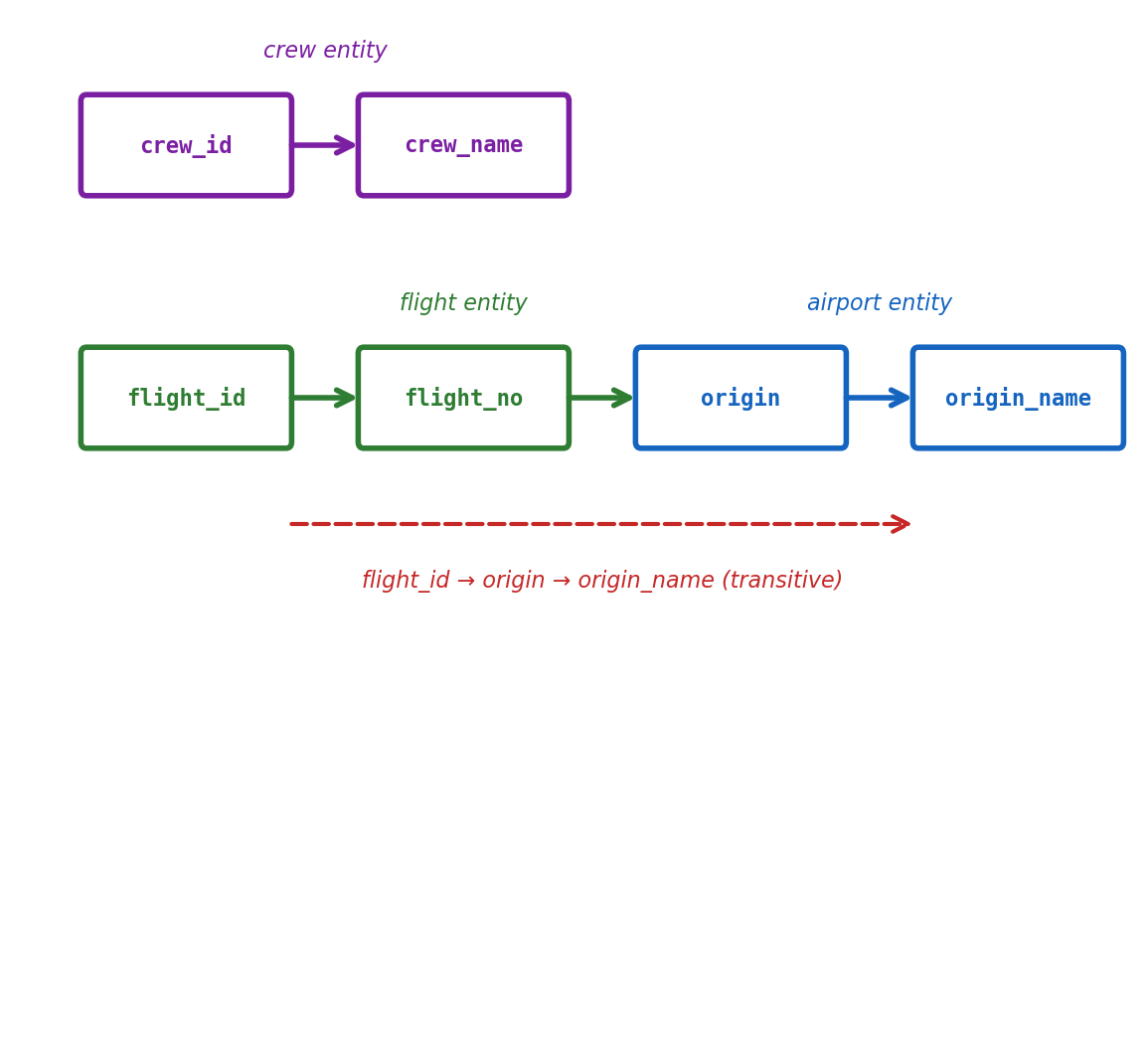

Transitive dependency: flight_id → origin → origin_name

The origin name depends on the origin code, not the flight. Storing it in the flights table duplicates it for every flight from that airport.

First Normal Form (1NF)

Each column holds a single atomic value. Each row is uniquely identifiable.

Violation — non-atomic values:

| crew_id | name | certifications |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | Chen | 737, 767, A320 |

| 102 | Okafor | 737 |

The certifications column holds a comma-separated list. Querying “which crew members are certified on 767” requires string parsing, not a simple comparison.

1NF — atomic values, separate rows or table:

Option 1: separate rows

| crew_id | name | certification |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | Chen | 737 |

| 101 | Chen | 767 |

| 101 | Chen | A320 |

| 102 | Okafor | 737 |

Option 2: separate table (better)

| crew_id | aircraft_type |

|---|---|

| 101 | 737 |

| 101 | 767 |

| 101 | A320 |

| 102 | 737 |

Eliminates the repeated crew_name and enables direct queries:

Second Normal Form (2NF)

In 1NF, plus: every non-key column depends on the entire primary key, not just part of it.

2NF violations only occur with composite primary keys — single-column keys cannot have partial dependencies.

Violation:

| crew_id | flight_id | role | crew_name | flight_number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 7 | captain | Chen | AA 100 |

| 102 | 7 | first_officer | Okafor | AA 100 |

| 101 | 15 | captain | Chen | DL 47 |

Primary key: (crew_id, flight_id)

crew_namedepends only oncrew_id— partial dependencyflight_numberdepends only onflight_id— partial dependencyroledepends on the full key(crew_id, flight_id)— correct

Result: "Chen" stored in every assignment row for crew 101.

2NF — decompose partial dependencies:

crew:

| crew_id | crew_name |

|---|---|

| 101 | Chen |

| 102 | Okafor |

flights: (already has flight_number)

crew_assignments:

| crew_id | flight_id | role |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | 7 | captain |

| 102 | 7 | first_officer |

| 101 | 15 | captain |

crew_name stored once per crew member. role depends on the full composite key — which crew member on which flight.

Third Normal Form (3NF)

In 2NF, plus: no non-key column depends on another non-key column. All non-key columns depend directly on the primary key.

Violation — transitive dependency:

| flight_id | flight_number | origin | origin_name | origin_tz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | AA 100 | LAX | Los Angeles Intl | America/Los_Angeles |

| 15 | DL 47 | ATL | Hartsfield-Jackson | America/New_York |

| 23 | UA 200 | LAX | Los Angeles Intl | America/Los_Angeles |

flight_id → origin(direct)origin → origin_name, origin_tz(direct, but origin is not a key)flight_id → origin → origin_name(transitive)

The airport name and timezone depend on the origin code, not on the flight. They belong in the airports table, not the flights table.

3NF — remove transitive dependencies:

flights:

| flight_id | flight_number | origin |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | AA 100 | LAX |

| 15 | DL 47 | ATL |

| 23 | UA 200 | LAX |

airports:

| airport_code | name | timezone |

|---|---|---|

| LAX | Los Angeles Intl | America/Los_Angeles |

| ATL | Hartsfield-Jackson | America/New_York |

Airport name stored once. "Los Angeles Intl" no longer duplicated across flights. Updating the name requires changing one row.

The aviation schema from section 02 is already in 3NF. Each table stores attributes that depend on that table’s primary key and nothing else.

Normalization Progression

Each step eliminates a class of dependency violation. The end state: each fact stored exactly once.

Denormalization as a Deliberate Trade-off

Normalization eliminates redundancy. But normalized data is distributed across tables, and reassembling it requires joins.

Normalized — correct, join-dependent:

SELECT b.booking_id, f.flight_number,

a.name AS airport

FROM bookings b

JOIN flights f ON b.flight_id = f.flight_id

JOIN airports a ON f.origin = a.airport_code

WHERE b.passenger_id = 42;Three tables joined. Airport name stored once — always consistent.

Cost: CPU and I/O for the join. Negligible at small scale; measurable at millions of rows with complex join graphs.

Denormalized — redundant, join-free:

One table, no joins, faster reads. But origin_name duplicated in every booking row.

Cost: storage, write complexity, anomaly risk. Updating an airport name means updating every booking row that references it — partial updates produce inconsistency.

The trade-off:

- Normalized — consistency guaranteed, reads require joins

- Denormalized — faster reads, consistency becomes the application’s responsibility

Denormalization Is the Foundation of NoSQL

NoSQL databases make denormalization a first-class design principle rather than a reluctant optimization.

Relational (normalized):

- Schema enforces structure

- Joins reassemble related data

- Writes are simple (one fact, one place)

- Reads may require multiple joins

- Horizontal scaling is difficult — joins require data co-location

Any query can combine any tables. Schema evolves by adding tables and relationships. The cost: join complexity at scale.

Document store (denormalized):

- Data stored as self-contained documents

- Related data embedded within the document

- No joins — everything for one request in one read

- Writes must update every copy of duplicated data

- Horizontal scaling straightforward — documents are independent

Each document contains everything needed to serve a request. The cost: managing redundancy and consistency across documents when the same fact is embedded in thousands of places.

Transactions and Concurrency

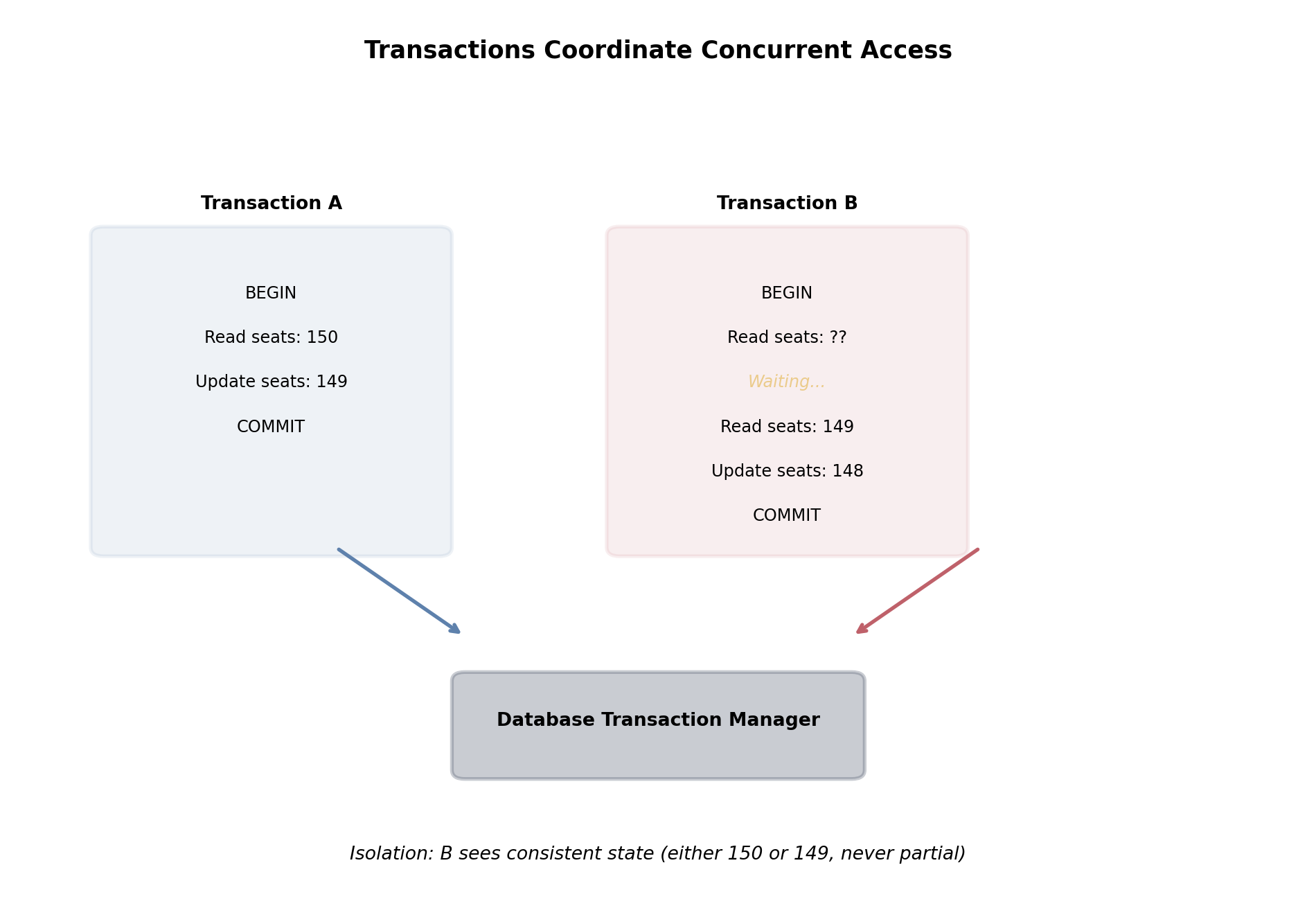

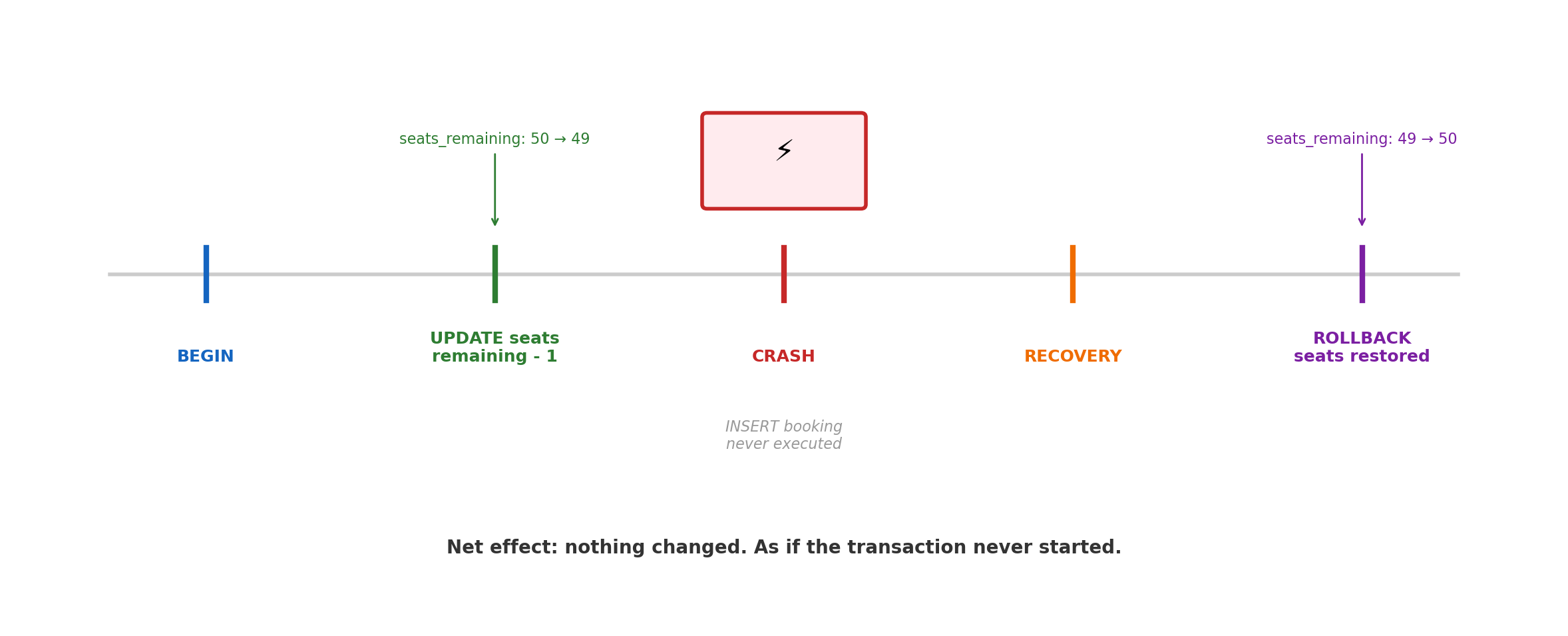

Transactions Group Operations into Atomic Units

A booking requires two writes: decrement the seat count, then insert the booking record. If the second fails, the first must be undone.

BEGIN;

UPDATE flights SET seats_remaining = seats_remaining - 1

WHERE flight_id = 7 AND seats_remaining > 0;

INSERT INTO bookings (passenger_id, flight_id, fare_class)

VALUES (42, 7, 'Y');

COMMIT;BEGIN — starts the transaction

COMMIT — makes all changes permanent

ROLLBACK — discards all changes since BEGIN

- Either both writes succeed, or neither takes effect

- No intermediate state is visible to other connections

- The database guarantees this even if the process crashes mid-transaction

Without a transaction:

UPDATE flights SET seats_remaining = seats_remaining - 1

WHERE flight_id = 7;

-- application crashes here

INSERT INTO bookings ...; -- never executes- Seat decremented but no booking created

- One fewer seat available, no record of why

- Manual correction required — if anyone notices

The transaction boundary defines what “one operation” means to the database.

ACID Properties

Four guarantees that transactions provide. Each addresses a specific failure mode.

Atomicity — all or nothing

- Transaction succeeds → all changes persist

- Transaction fails (crash, error, rollback) → no changes persist

- No partial results visible to anyone

Consistency — valid state to valid state

- All constraints checked at commit time

- Foreign keys, CHECK, UNIQUE, NOT NULL — all enforced

- If any constraint fails, the entire transaction rolls back

- Application-level rules (e.g., “a pilot can only work 8 hours”) remain the application’s responsibility

Isolation — concurrent transactions don’t interfere

- Transaction A’s uncommitted changes are invisible to transaction B (at most isolation levels)

- Behaves as if transactions ran sequentially

- The database achieves this while actually running them concurrently

Durability — committed data survives failures

- After COMMIT returns, the data is on stable storage

- Write-ahead log (WAL) ensures this: log entry written and fsynced before commit acknowledged

- Server loses power one millisecond after COMMIT → data intact on restart

Atomicity Under Failure

Concurrent Transactions Interleave

Multiple connections execute transactions simultaneously. The database interleaves their operations.

Both transactions read seats_remaining = 1. Both set it to 0. Both commit. The second transaction’s write overwrites the first — a lost update. Neither transaction saw the other’s changes.

Concurrency Anomalies

Dirty read — reading uncommitted data

- Tx A updates a seat count but hasn’t committed

- Tx B reads the updated (uncommitted) value

- Tx A rolls back

- Tx B acted on data that never existed

Non-repeatable read — same query, different results

- Tx A reads

seats_remaining = 5 - Tx B updates

seats_remaining = 3and commits - Tx A reads again:

seats_remaining = 3 - Same query, same transaction, different answer

Phantom read — new rows appear

- Tx A queries all bookings for flight 7: 48 rows

- Tx B inserts a new booking for flight 7 and commits

- Tx A queries again: 49 rows

- A row that didn’t exist now appears

Lost update — concurrent write collision

- Tx A reads

seats_remaining = 1 - Tx B reads

seats_remaining = 1 - Tx A writes

seats_remaining = 0, commits - Tx B writes

seats_remaining = 0, commits - Two bookings, one seat

Each anomaly represents a different way concurrent transactions can interfere. Isolation levels control which anomalies the database prevents.

Isolation Levels

Four standard levels, each preventing a progressively larger set of anomalies. Higher isolation costs more throughput.

| Level | Dirty read | Non-repeatable read | Phantom read | Lost update |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| READ UNCOMMITTED | possible | possible | possible | possible |

| READ COMMITTED | prevented | possible | possible | possible |

| REPEATABLE READ | prevented | prevented | possible | prevented |

| SERIALIZABLE | prevented | prevented | prevented | prevented |

READ COMMITTED (PostgreSQL default)

- Each statement sees only data committed before that statement began

- Different statements within the same transaction may see different data

- Sufficient for most applications

Isolation in Practice

The seat booking under READ COMMITTED:

BEGIN;

SELECT seats_remaining FROM flights

WHERE flight_id = 7; -- returns 1

-- another transaction commits here,

-- setting seats_remaining to 0

UPDATE flights

SET seats_remaining = seats_remaining - 1

WHERE flight_id = 7

AND seats_remaining > 0;

-- rows affected: 0 (condition no longer true)

-- application checks: no rows updated → abort

ROLLBACK;The WHERE seats_remaining > 0 guard prevents overselling — but only because the UPDATE sees the committed state at the time the UPDATE runs, not the state at the time of the SELECT.

Application-level patterns:

- Optimistic concurrency — read, compute, write with a guard condition. If the guard fails, retry.

- SELECT … FOR UPDATE — acquire a row lock at read time, preventing concurrent modification until commit.

BEGIN;

SELECT seats_remaining FROM flights

WHERE flight_id = 7

FOR UPDATE; -- locks the row

-- guaranteed: no other transaction can

-- modify this row until we COMMIT

UPDATE flights

SET seats_remaining = seats_remaining - 1

WHERE flight_id = 7;

INSERT INTO bookings ...;

COMMIT;FOR UPDATE trades concurrency for correctness — other transactions reading this row must wait.

Locking: The Mechanism Behind Isolation

Databases enforce isolation through locks — markers that control which transactions can access which data.

Lock granularity:

- Row-level — locks one row; other rows in the same table are unaffected

- Table-level — locks the entire table; all other access blocked

- Row-level is the default for most operations

Lock types:

- Shared (read) lock — multiple transactions can hold simultaneously; blocks writers

- Exclusive (write) lock — only one holder; blocks all other access to that row

Lock duration:

- Held until the transaction ends (COMMIT or ROLLBACK)

- Long transactions hold locks longer → more contention

Contention:

Two transactions updating different flights:

- Tx A locks flight 7, Tx B locks flight 15

- No contention — proceed concurrently

Two transactions updating the same flight:

- Tx A locks flight 7

- Tx B tries to lock flight 7 → waits

- Tx A commits → Tx B proceeds

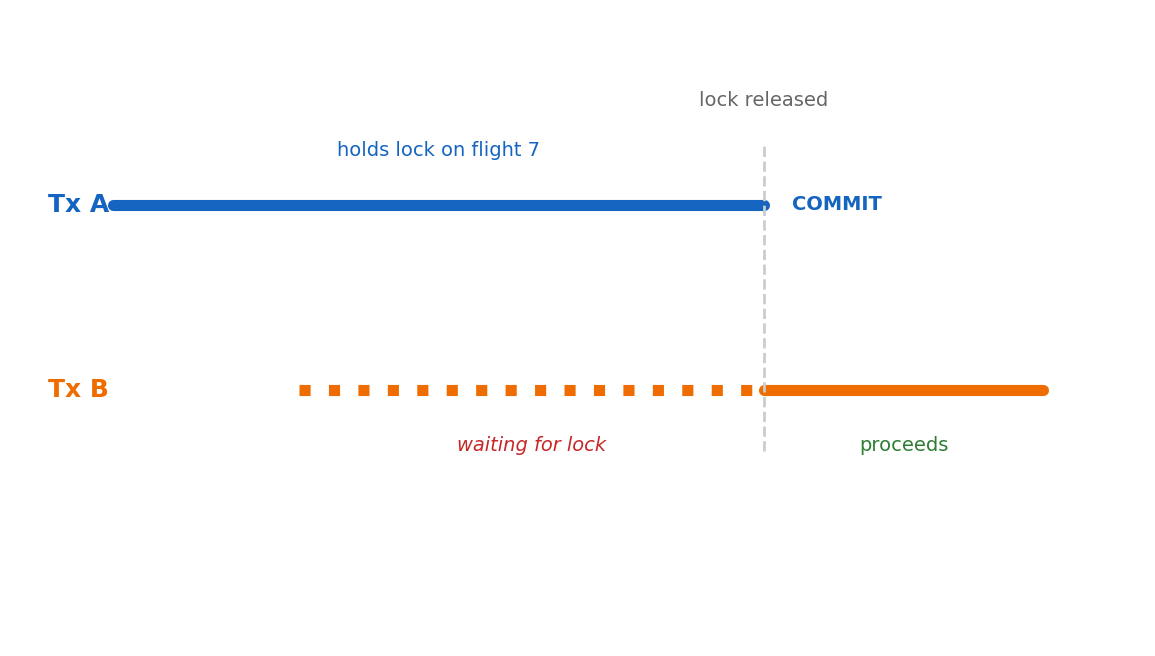

Lock wait time is the direct cost of isolation. Throughput depends on how often transactions contend for the same rows and how long they hold locks.

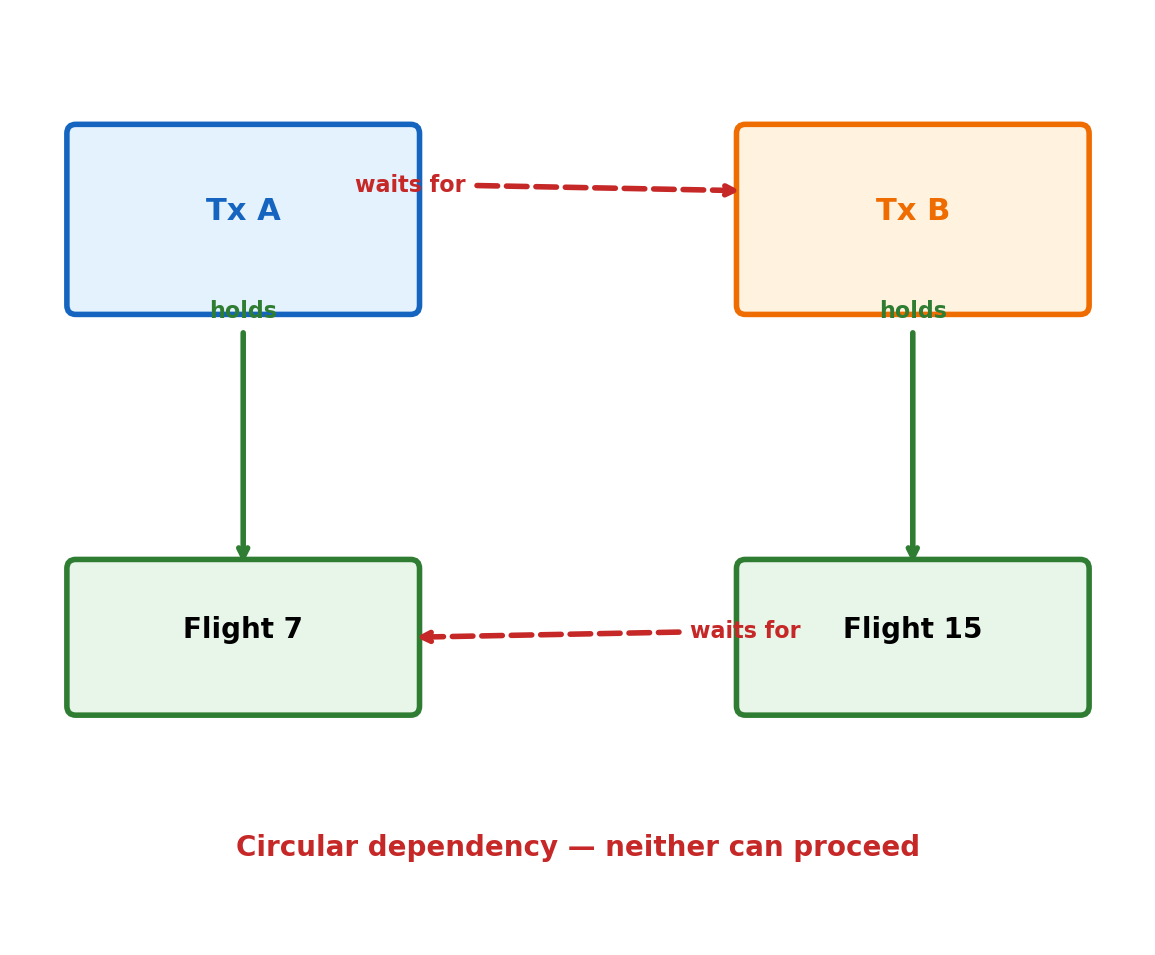

Deadlock

Two transactions, each holding a lock the other needs.

Sequence:

- Tx A locks flight 7

- Tx B locks flight 15

- Tx A requests lock on flight 15 → waits (Tx B holds it)

- Tx B requests lock on flight 7 → waits (Tx A holds it)

Neither can proceed. Both will wait forever.

Resolution:

- The database detects the cycle (lock dependency graph)

- Aborts one transaction (the “victim”)

- Victim receives an error; its changes are rolled back

- The other transaction proceeds

ERROR: deadlock detected

DETAIL: Process 1234 waits for ShareLock

on tuple (0,5) of relation "flights";

blocked by process 5678.Deadlocks are not bugs — they are an expected consequence of fine-grained locking. Applications must handle the error and retry.

Indexes and Query Performance

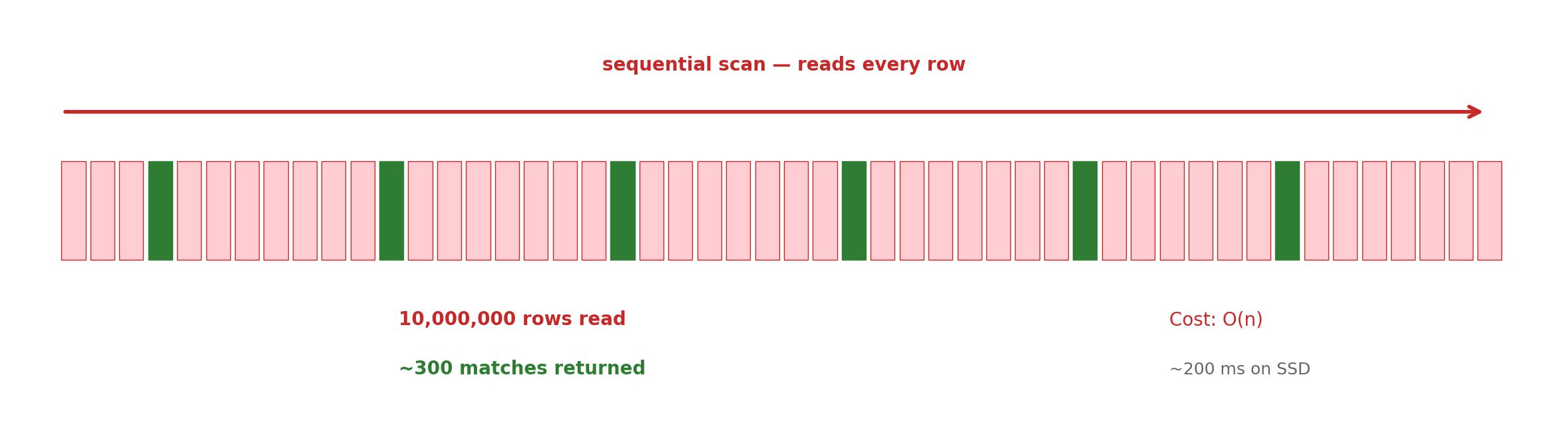

Without an Index, Every Query Scans Every Row

No index on origin. The database has no way to locate LAX flights without examining every row.

Sequential scan — the default when no index exists. Cost is proportional to table size, regardless of how many rows actually match. A 10-million-row table takes the same time whether the query matches 3 rows or 3 million.

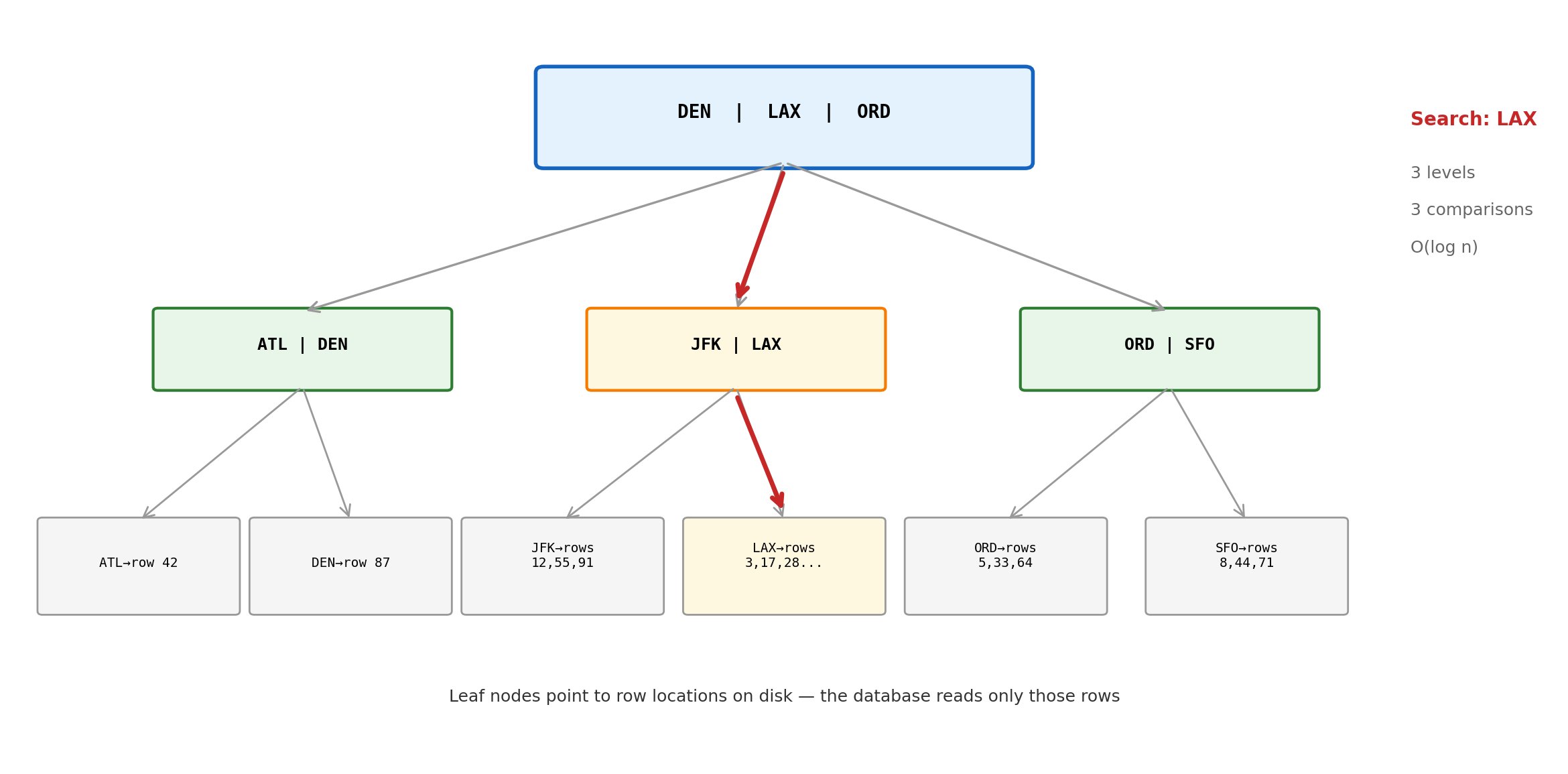

B-Tree: Sorted Lookup Structure

An index is a separate data structure maintained alongside the table. The dominant type is the B-tree — a balanced, sorted tree that maps column values to row locations.

B-tree properties:

- Sorted — supports equality (

= 'LAX') and range queries (BETWEEN 'LAX' AND 'ORD') - Balanced — all leaf nodes at the same depth; worst-case lookup is O(log n)

- 10 million rows → ~23 levels (log₂ 10⁷ ≈ 23). Three disk reads instead of ten million.

- Maintained automatically — every INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE updates the index

Creating and Using Indexes

Before the index:

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM flights WHERE origin=‘LAX’;

Seq Scan on flights Filter: (origin = ‘LAX’) Rows Removed by Filter: 9700 Actual Time: 185.3 ms

After the index:

EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM flights WHERE origin=‘LAX’;

Index Scan using idx_flights_origin Index Cond: (origin = ‘LAX’) Actual Time: 0.8 ms

Same query. Same data. 230x faster.

The optimizer decides whether to use the index.

- Selective query (few matches) → index scan

- Broad query (most rows match) → seq scan is cheaper

WHERE origin = 'LAX'on a table where 3% of flights are from LAX → indexWHERE seats_remaining > 0on a table where 95% of flights have seats → seq scan (faster to just read everything)

The decision is automatic. The optimizer maintains statistics on value distributions and chooses the cheapest plan.

CREATE INDEX makes the option available. The optimizer decides when to use it.

The Index Trade-off

Indexes are not free. Every index maintained is a cost paid on every write.

Benefits — read performance:

- Equality lookups: O(log n) vs O(n)

- Range queries: read a contiguous slice of sorted leaves

- ORDER BY on indexed column: already sorted, no sort step

- JOIN on indexed column: lookup instead of nested loop

Costs — write performance and storage:

- Every INSERT adds an entry to every index on the table

- Every UPDATE to an indexed column updates the index

- Every DELETE removes an index entry

- Each index is a full copy of the indexed columns, sorted differently

- A table with 5 indexes: every write does 6 operations (1 table + 5 indexes)

When to index:

- Columns in WHERE clauses (filter predicates)

- Columns in JOIN conditions (foreign keys)

- Columns in ORDER BY (avoid sort step)

- High-selectivity columns (few matching rows)

When not to index:

- Small tables (seq scan is fast enough)

- Columns rarely used in queries

- Low-selectivity columns (boolean, status with 3 values)

- Write-heavy tables where read performance is less critical

A table with an index on every column pays write overhead and storage cost for each — including indexes no query ever uses. Index selection should be driven by actual query patterns.

Composite Indexes

An index on multiple columns. Column order determines which queries it can serve.

The index sorts by origin first, then by date within each origin.

Queries this index serves:

Queries this index does NOT serve:

The index is sorted by origin first — without a value for origin, there is no efficient entry point. The database must scan the entire index, no better than a seq scan.

Column order is a design decision driven by query patterns:

(origin, departure_date)— serves “flights from LAX this week”(departure_date, origin)— serves “all flights today from any airport”

Same columns, different ordering, different queries served efficiently.

Foreign Key Columns Need Indexes

Joins traverse foreign key relationships. Without an index on the FK column, every join becomes a sequential scan of the referenced table.

PostgreSQL does not automatically index foreign key columns.

CREATE TABLE bookings (

booking_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

flight_id INTEGER REFERENCES flights(flight_id),

...

);

-- flights(flight_id) has a PK index

-- bookings(flight_id) has NO indexFor each LAX flight, the database scans every row in bookings to find matches:

- 300 LAX flights × 1M bookings = 300 million row comparisons

With an index on the foreign key:

Each LAX flight does an index lookup into bookings:

- 300 flights × O(log n) ≈ 300 × 20 = 6,000 comparisons

- 300 million → 6,000. Same query, same data.

Every foreign key column should generally have an index. The write cost of maintaining it is almost always justified by join performance.

MySQL/InnoDB creates FK indexes automatically. PostgreSQL does not — FK index omissions are a frequent source of production performance issues in PostgreSQL deployments.

Relational Architecture at Scale

Fixed Schema: Rigidity as Enforcement

Every row in a table has the same columns. A flight has an origin, a destination, a departure time — regardless of whether the flight is domestic or international, cargo or passenger, scheduled or charter.

Adding a column affects every row.

All existing flights now have customs_required = NULL — the column exists for every row, including domestic flights where it has no meaning. Charter flights may need columns that scheduled flights do not.

Heterogeneous entities fit awkwardly in fixed schemas. When subtypes have substantially different attributes:

- Single table with many nullable columns — sparse, type-dependent NULLs

- Multiple tables with shared keys (ISA pattern) — requires joins

- Both are valid; both have costs

ALTER TABLE in production is an operational event.

On a table with 100 million rows:

- Adding a column with a DEFAULT value rewrites every row (PostgreSQL < 11)

- Adding a NOT NULL constraint requires scanning every row to verify

- Changing a column type requires rewriting and revalidating every value

- These operations acquire locks that block concurrent writes

Schema changes require coordination with application code:

- New column the application doesn’t know about → harmless

- Removed column the application still references → failure

Schema migration tools (Flyway, Alembic, Django migrations) manage this — versioned scripts applied in sequence, with rollback capability.

Schema Rigidity Is Also Schema Enforcement

The same property that makes schema evolution expensive is what prevents invalid data.

Rigid schema guarantees:

- Every flight has an origin —

NOT NULLenforced - Every airport code is exactly 3 characters —

CHAR(3)enforced - Every booking references a real flight — foreign key enforced

- Seat counts never go negative — CHECK constraint enforced

These guarantees hold for every row, every application, every access path. No application can insert a flight without an origin. No background job can set a seat count to -1.

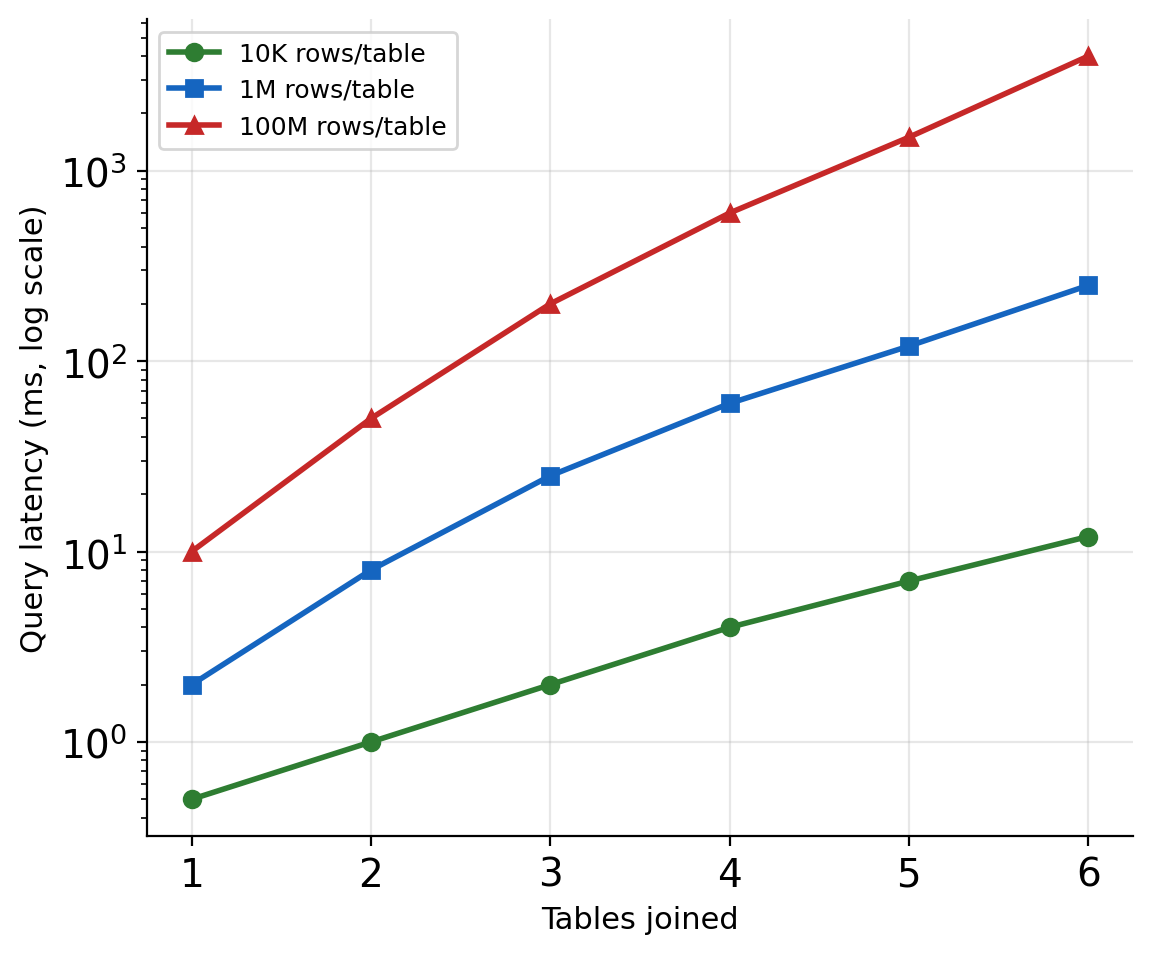

Flexible schema trades this for adaptability: