NoSQL and Distributed Databases

EE 547 - Unit 5

Fall 2025

Outline

Relational Model Limitations

Structural and Scale Constraints

- Object-relational impedance mismatch

- JOIN complexity grows super-linearly

- Schema rigidity vs sparse data

- Horizontal partitioning for capacity

- Replication trade-offs and consistency models

- CAP theorem constraints

- Consistency level tuning

- Access pattern-driven design

- Denormalization trade-offs

NoSQL Data Models

- GET/PUT operations with O(1) access

- Hierarchical document structure

- Atomic operations and race conditions

- Sparse columnar storage for time-series

- Native graph traversal vs JOIN-based queries

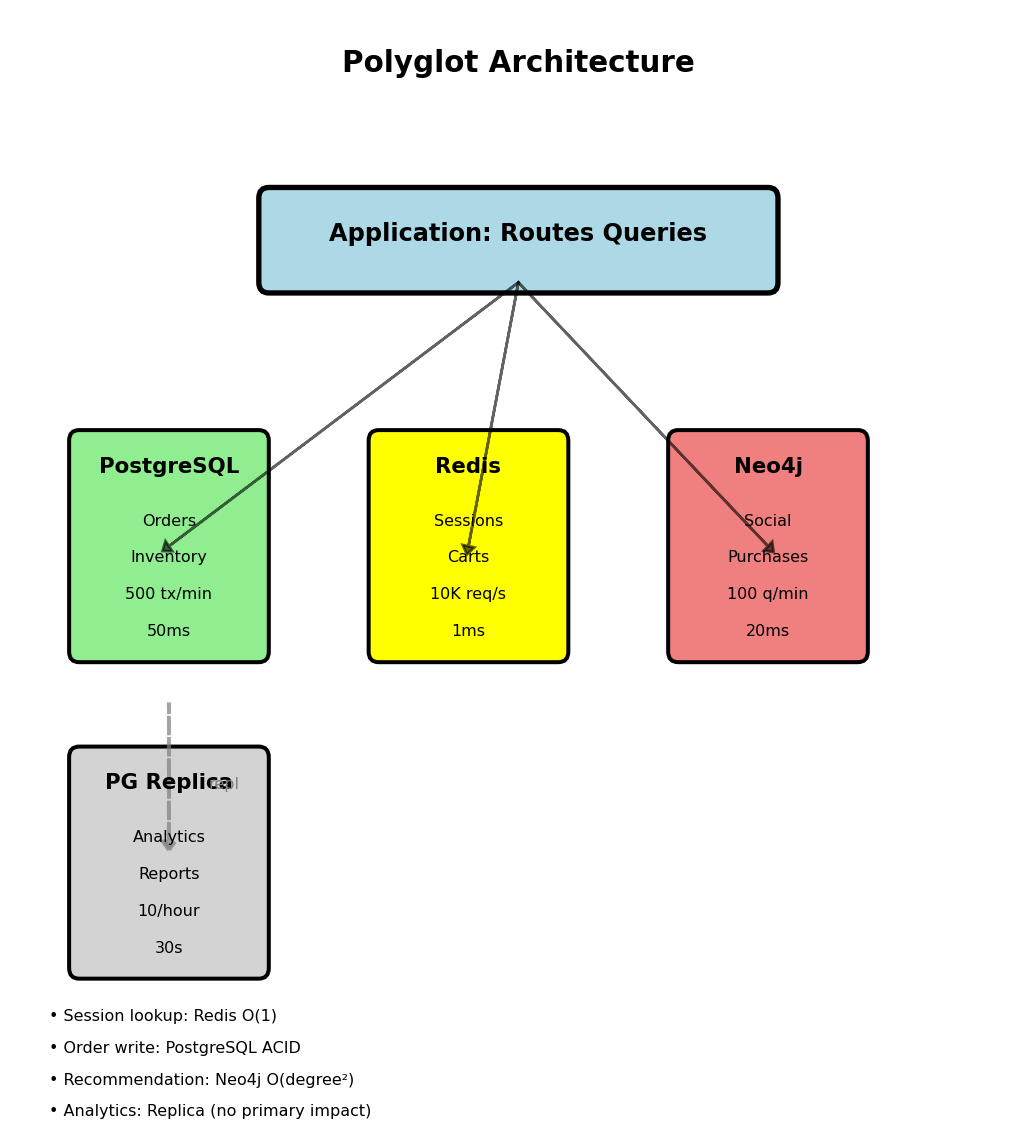

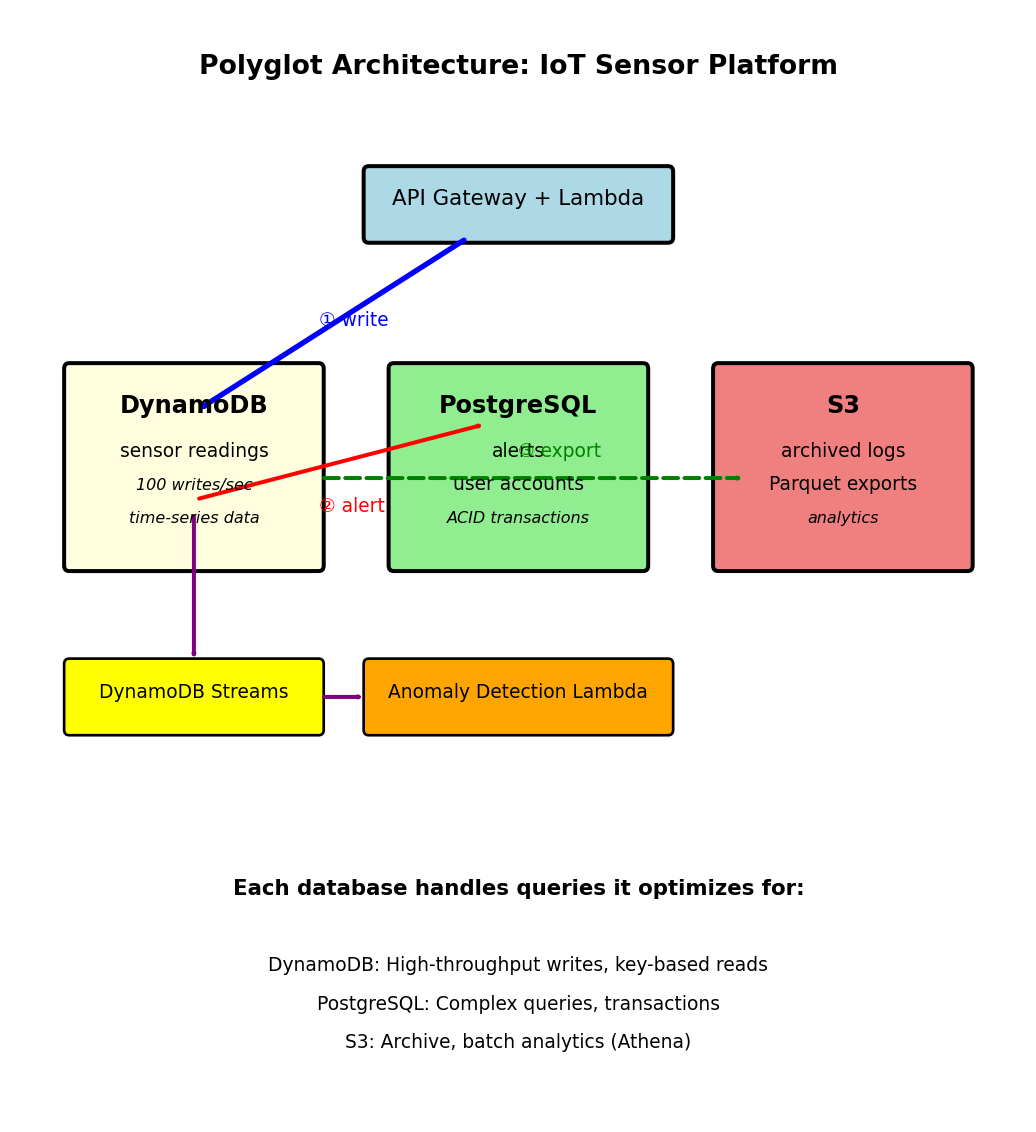

- Polyglot persistence trade-offs

- Managed database services

When Relational Models Break Down

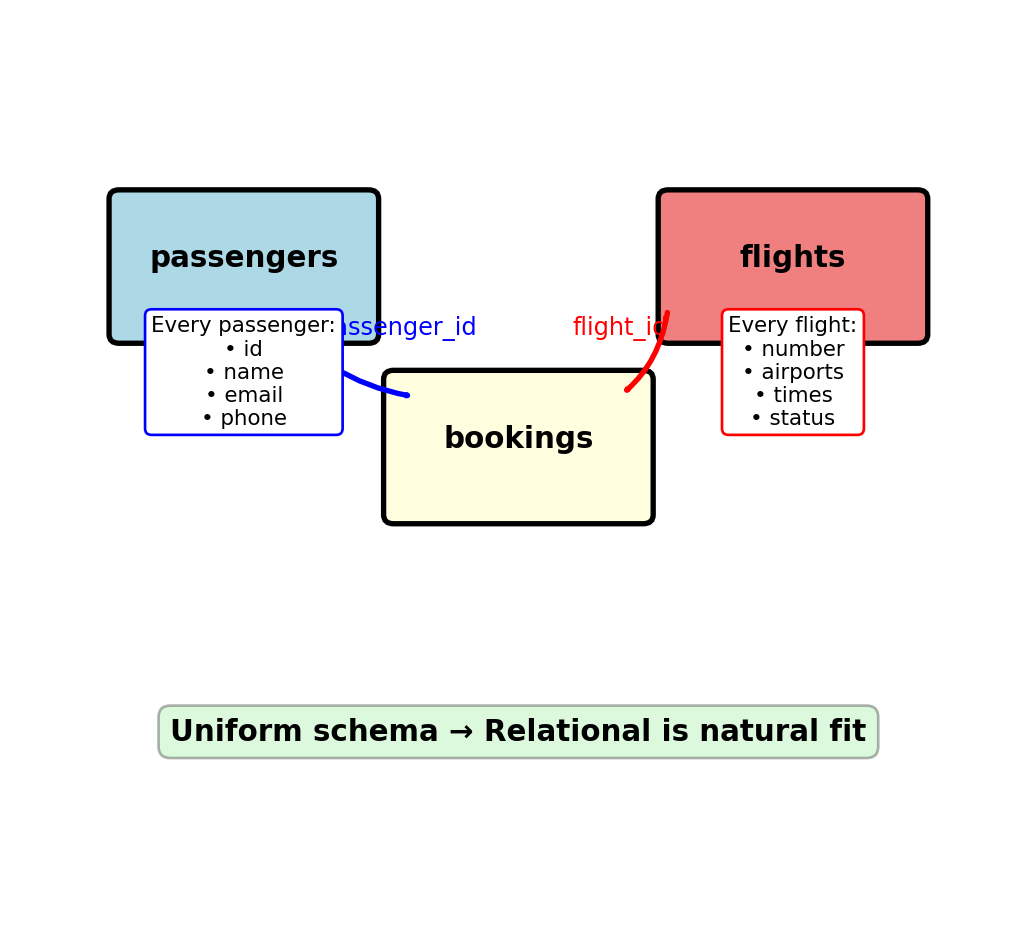

Relational Models Excel at Structured, Uniform Data

Flight booking schema works because:

- Uniform structure: Every flight has same attributes

- Clear relationships: Foreign keys model real entities

- Predictable queries: Find bookings, flights on routes

- This fit between data shape and model is not universal

When data and queries match structure, relational wins

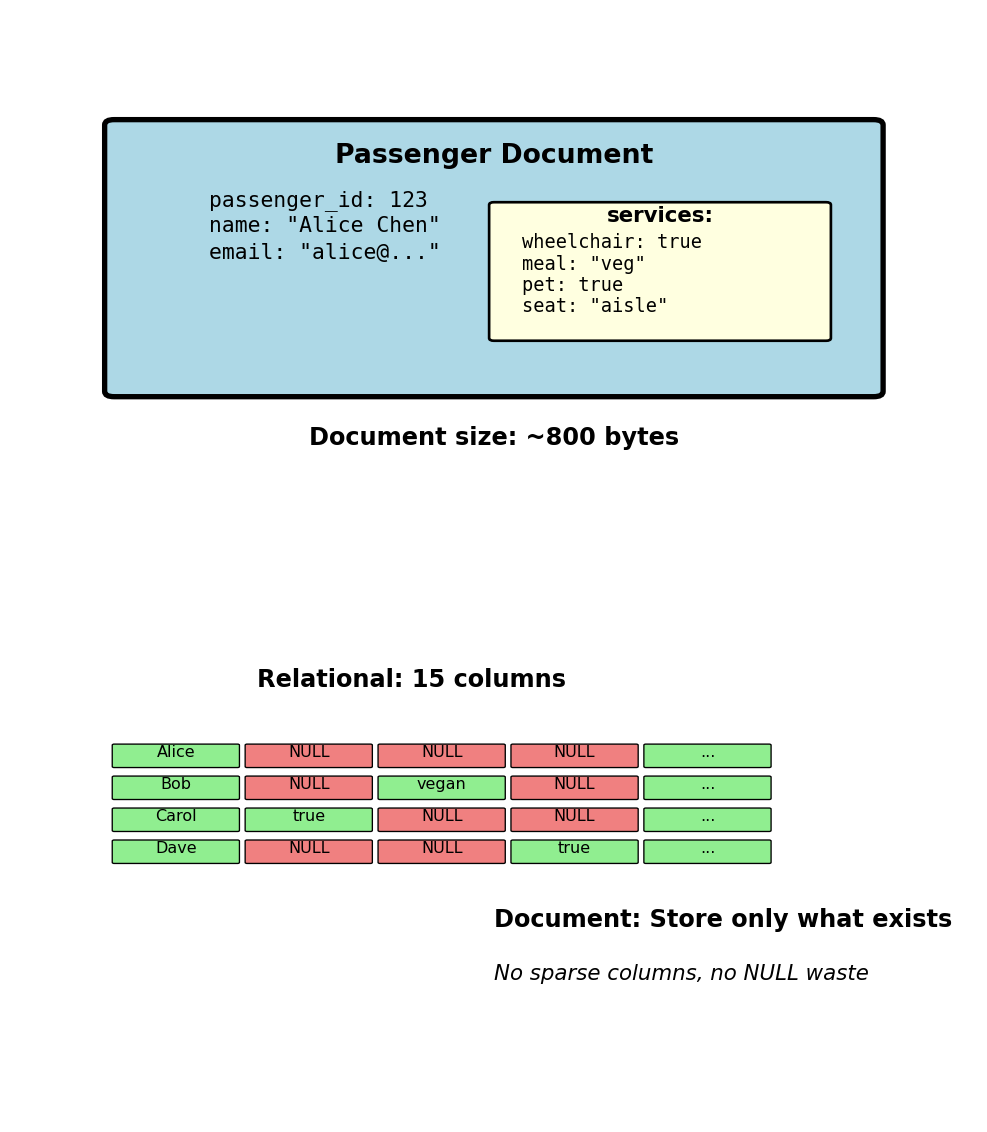

Schema Rigidity When Data Varies

Add special services to passengers:

- Wheelchair assistance

- Meal preferences (vegetarian, gluten-free, kosher)

- Pet carrier

- Unaccompanied minor

- Medical oxygen

- Extra legroom request

Relational approach 1: Add columns

Problem: Most passengers have mostly NULLs (90% of cells)

Relational approach 2: Services table

Problem: Loses type safety, querying awkward

-- Find passengers needing wheelchair

SELECT DISTINCT passenger_id

FROM passenger_services

WHERE service_key = 'wheelchair'

AND service_value = 'true';

-- Complex: wheelchair AND vegetarian

SELECT ps1.passenger_id

FROM passenger_services ps1

JOIN passenger_services ps2

ON ps1.passenger_id = ps2.passenger_id

WHERE ps1.service_key = 'wheelchair'

AND ps2.service_key = 'meal_pref'

AND ps2.service_value = 'vegetarian';Neither approach feels natural — data has variable structure per entity

Approach 1 storage example:

| passenger_id | name | wheelchair | meal | pet | oxygen | … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice | NULL | NULL | NULL | NULL | … |

| 2 | Bob | NULL | vegan | NULL | NULL | … |

| 3 | Carol | true | NULL | NULL | NULL | … |

With 10,000 passengers: 10,000 rows × 15 service columns = 150,000 cells, ~135,000 NULL values

Variable Schema Problem Generalizes

E-commerce products:

Books:

- ISBN: VARCHAR(13)

- author: VARCHAR(100)

- pages: INT

- publisher: VARCHAR(100)

Electronics:

- voltage: INT

- warranty_months: INT

- power_watts: INT

- battery_type: VARCHAR(50)

Clothing:

- size: VARCHAR(10)

- material: VARCHAR(100)

- care_instructions: TEXT

- fit_type: VARCHAR(50)

Relational solution?

- Single products table with 50+ columns, mostly NULL

- product_attributes table (key-value pairs)

- Separate tables per category (breaks product queries)

IoT sensor data:

Temperature sensors:

- celsius: FLOAT

- calibration_date: DATE

Motion sensors:

- x_accel: FLOAT

- y_accel: FLOAT

- z_accel: FLOAT

- sensitivity: INT

Camera sensors:

- image_url: VARCHAR(500)

- resolution_width: INT

- resolution_height: INT

- fps: INT

- codec: VARCHAR(20)

Pattern: Entity type is uniform (product, sensor), but attributes vary within type

Relational model assumes: All entities of same type have same attributes

Reality: Many domains have heterogeneous attributes

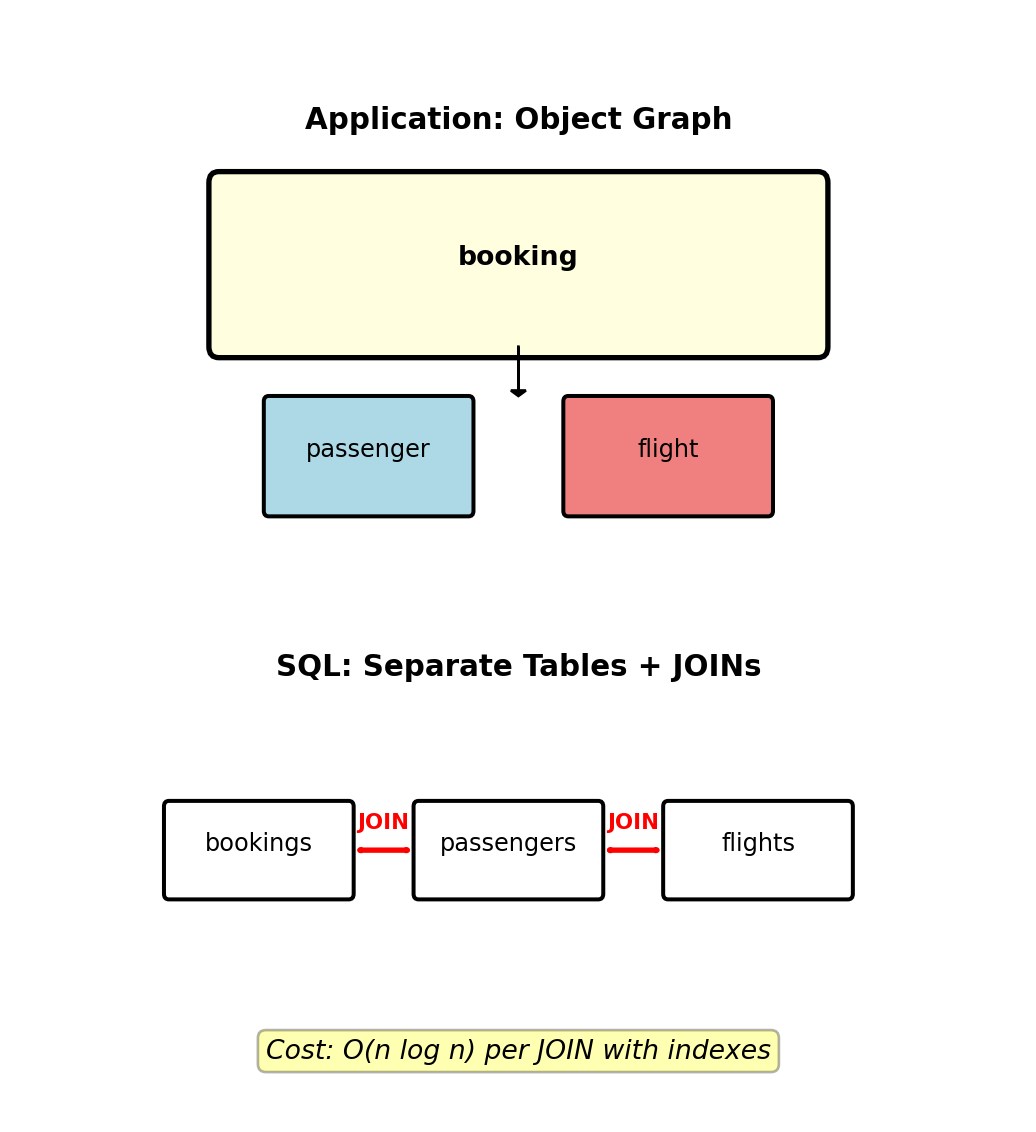

Nested Data Requires JOIN Operations for Reassembly

Application code thinks in objects:

SQL requires JOIN to reassemble:

Computational cost:

- Each JOIN: O(n log n) at best with indexes

- Three JOINs for three-level nesting

- Deeply nested structures → multiple JOINs

Worse: Comments on posts on forums

Impedance mismatch: Object hierarchy vs tabular relations

Every nested access = JOIN operation

Impedance Mismatch - Serialization Round-Trips

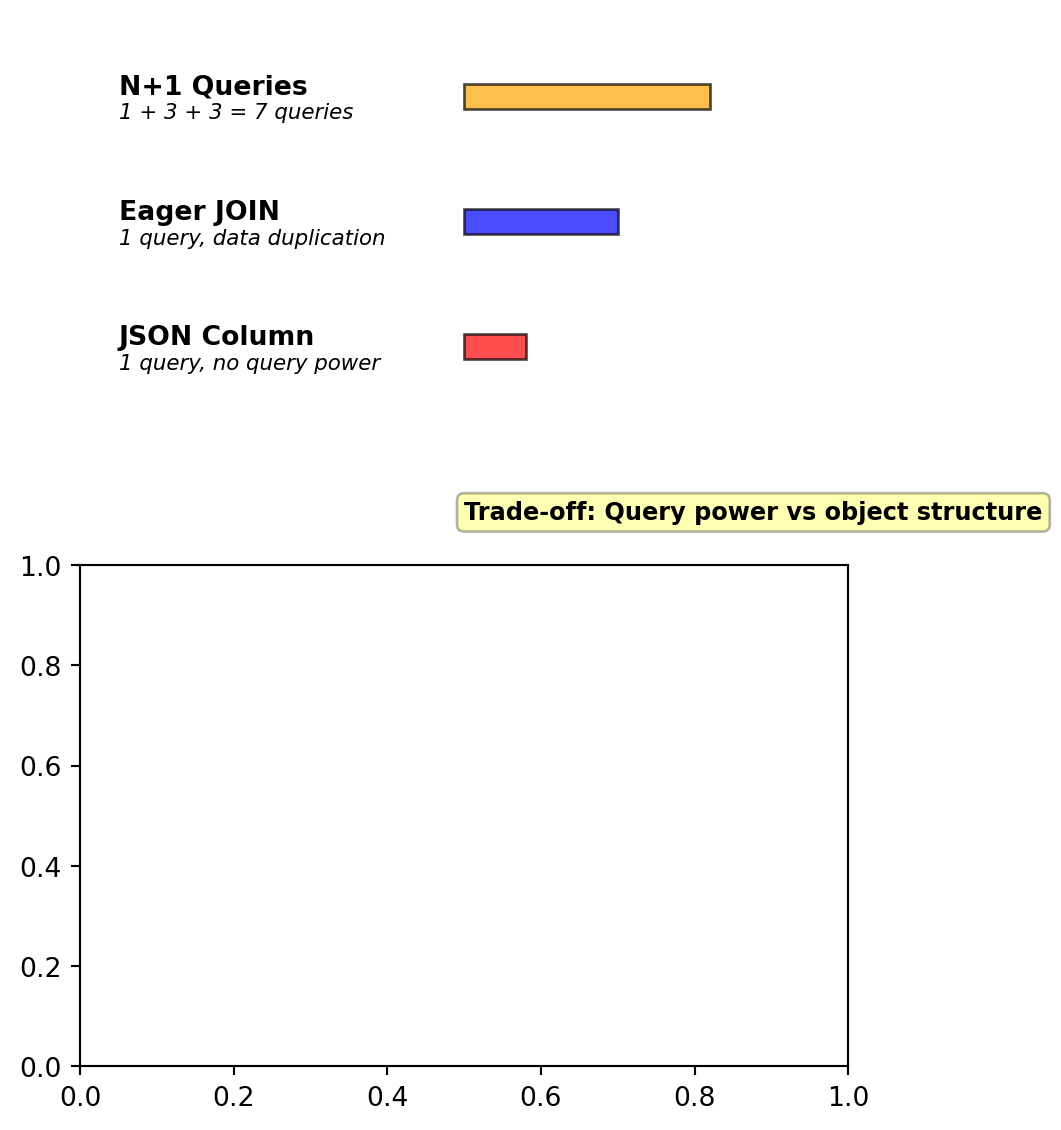

Impedance mismatch: Application code operates on object graphs, databases store flat tables. Moving data between these representations requires expensive translation.

Loading a passenger with 3 bookings and flight details:

Eager loading with JOINs:

Result: Duplicated passenger data × 3 rows (one per booking)

Alternative: Serialize entire object as JSON

Problem: Lose query capability, indexing, constraints

Load time for 1 passenger + 3 bookings:

- N+1 Queries: 45ms (7 roundtrips)

- Eager JOIN: 12ms (data duplication across rows)

- JSON Column: 3ms (no additional queries, but limited query power)

Each approach has serious drawbacks

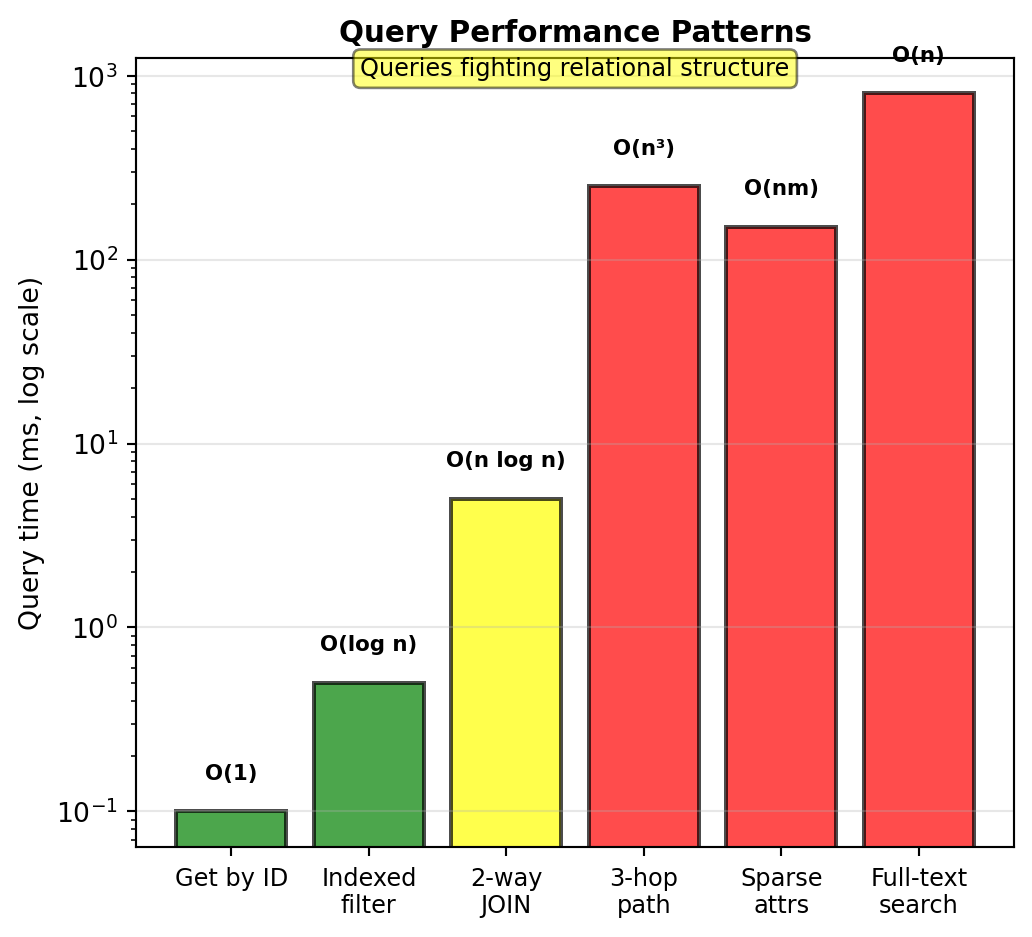

Query Patterns That Fight Relational Structure

Relational optimized for:

- Get entity by ID: O(1) with primary key

- Filter on indexed columns: O(log n)

- JOIN related tables: O(n log n)

Problematic patterns:

1. Path queries:

-- Flights connecting through exactly 2 hubs

SELECT f1.flight_number, f2.flight_number, f3.flight_number

FROM flights f1

JOIN flights f2 ON f1.arrival_airport = f2.departure_airport

JOIN flights f3 ON f2.arrival_airport = f3.departure_airport

WHERE f1.departure_airport = 'LAX'

AND f3.arrival_airport = 'LHR'

AND f1.arrival_airport NOT IN ('LAX', 'LHR')

AND f2.arrival_airport NOT IN ('LAX', 'LHR');Self-JOINs explode with path length

2. Sparse attribute filters:

-- Passengers with (gluten-free OR wheelchair) AND pet

SELECT DISTINCT ps1.passenger_id

FROM passenger_services ps1

WHERE ps1.passenger_id IN (

SELECT passenger_id FROM passenger_services

WHERE (service_key = 'meal' AND service_value = 'gluten-free')

OR (service_key = 'wheelchair' AND service_value = 'true')

)

AND ps1.passenger_id IN (

SELECT passenger_id FROM passenger_services

WHERE service_key = 'pet_carrier' AND service_value = 'true'

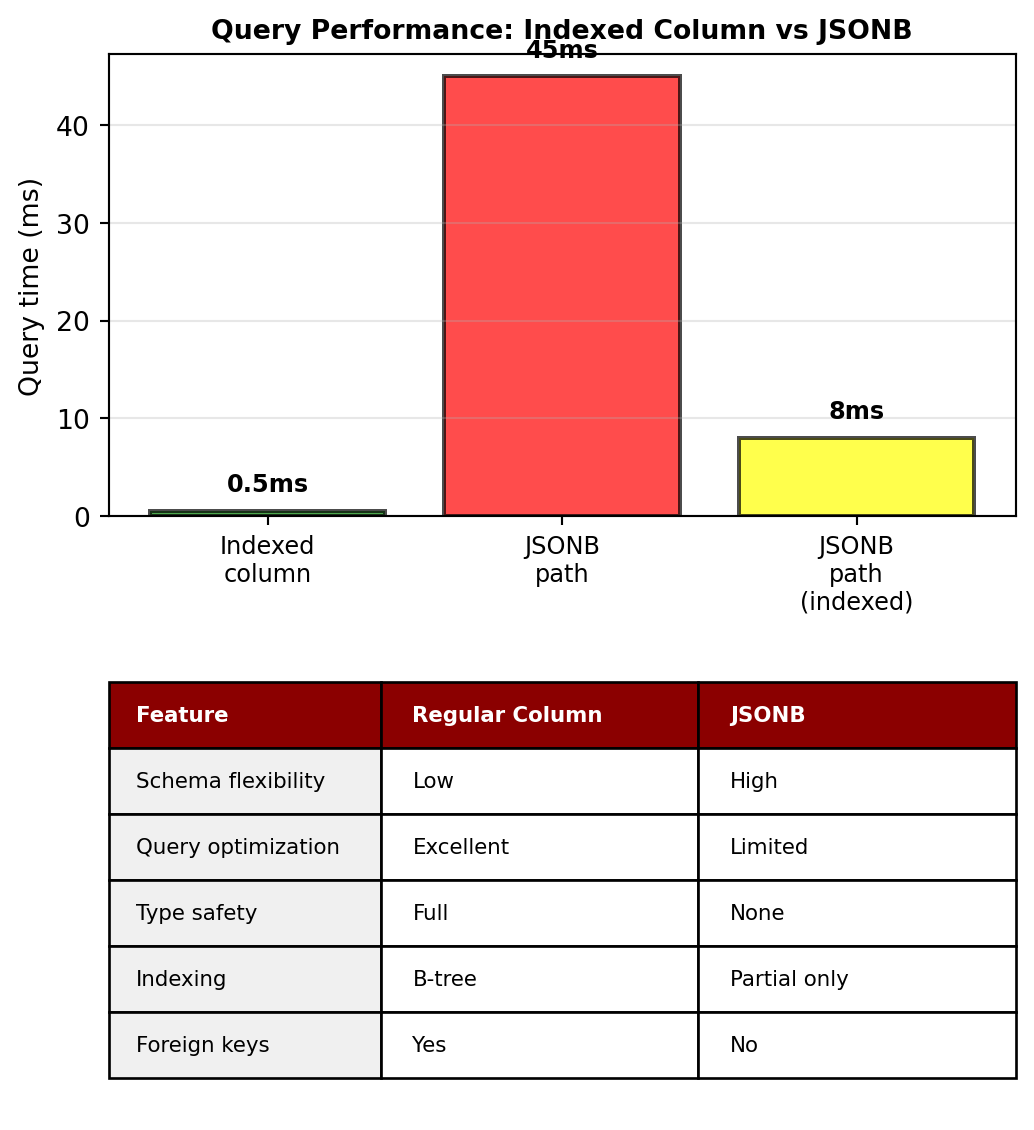

);JSON Columns Provide Flexibility But Limits Query Power

PostgreSQL JSONB, MySQL JSON type:

ALTER TABLE passengers ADD COLUMN services JSONB;

-- Store variable data as JSON

INSERT INTO passengers (id, name, email, services)

VALUES (1, 'Alice', 'alice@example.com',

'{"wheelchair": true, "meal": "vegetarian"}');

INSERT INTO passengers (2, 'Bob', 'bob@example.com',

'{"meal": "gluten-free", "pet_carrier": true, "extra_legroom": true}');Querying JSON data:

Problems:

- Query optimization: Cannot use B-tree indexes on nested paths efficiently

- Partial indexes help but don’t solve fundamental issue

- Type constraints lost: Everything is text in JSON

- No foreign key relationships inside JSON

Performance comparison:

Result: Relational overhead without relational benefits for nested data

Better solutions exist when data is fundamentally non-tabular

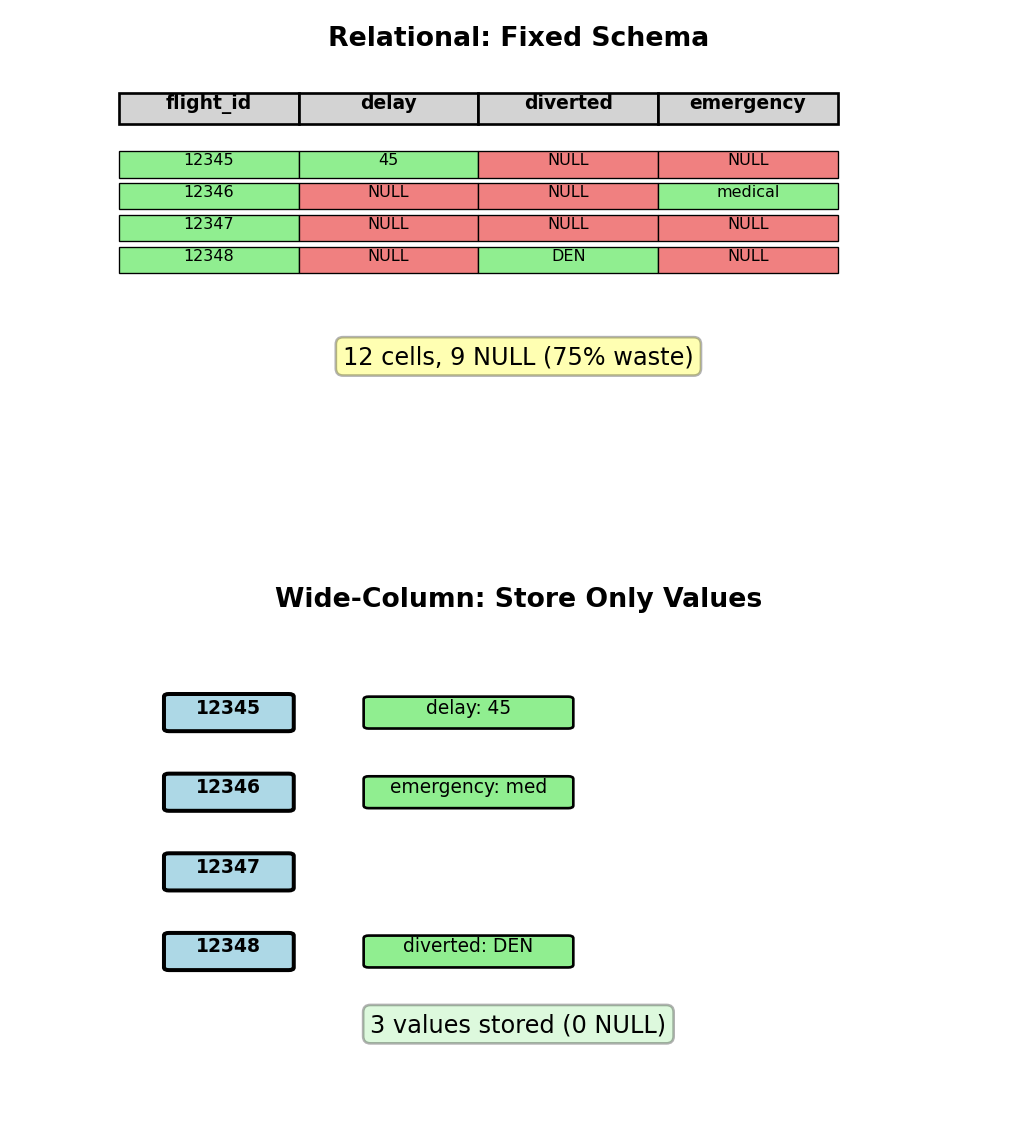

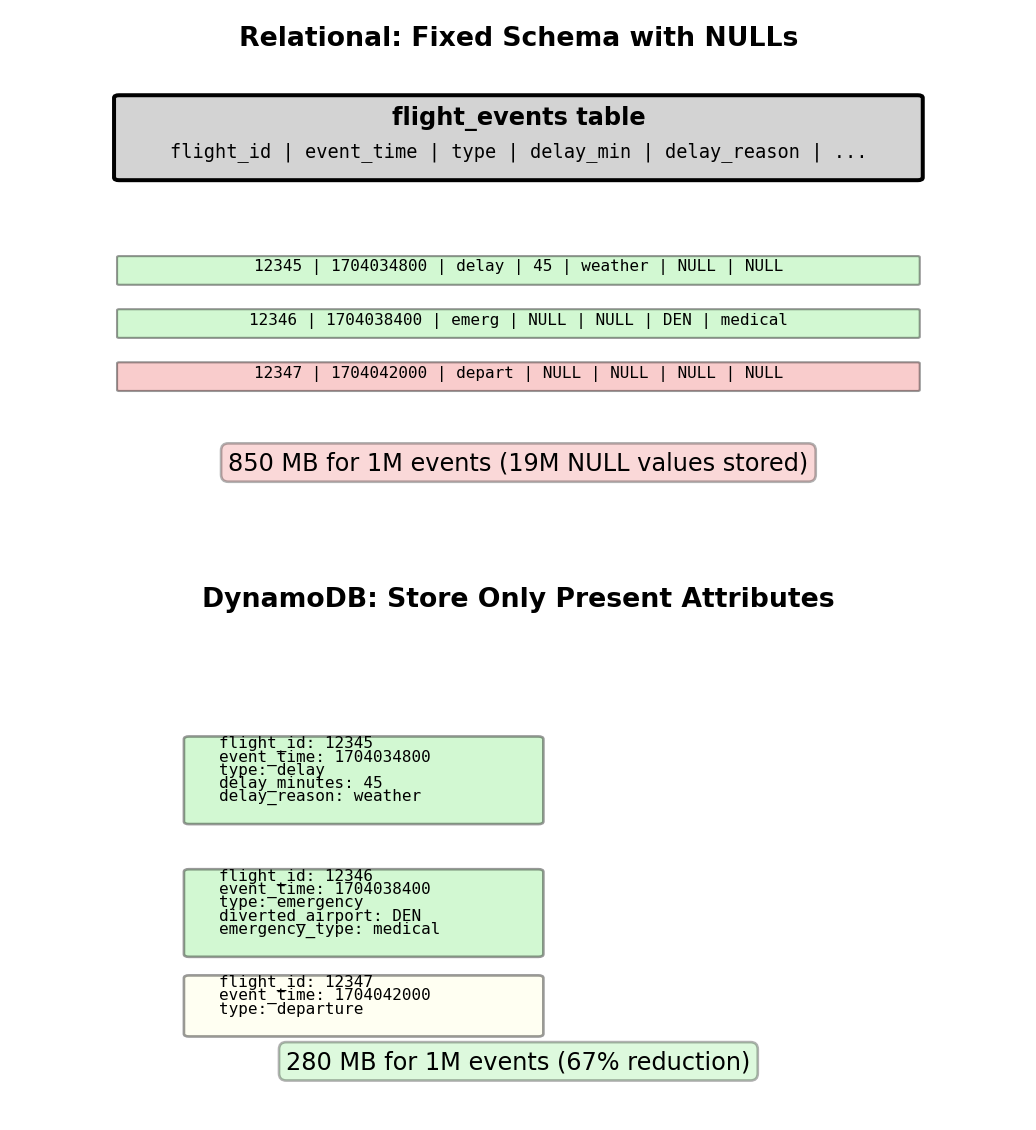

Sparse Data and NULL Proliferation

Add event tracking to flights:

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN delay_reason VARCHAR(100);

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN delay_minutes INT;

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN diverted_airport CHAR(3);

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN emergency_landing BOOLEAN;

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN diversion_reason TEXT;

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN emergency_type VARCHAR(50);

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN emergency_services BOOLEAN;

ALTER TABLE flights ADD COLUMN passenger_medical BOOLEAN;

-- ...15 more event-specific columnsMost flights: NULL for all special event fields

| flight_id | delay_reason | diverted | emergency | … |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1001 | NULL | NULL | NULL | … |

| 1002 | NULL | NULL | NULL | … |

| 1003 | weather | NULL | NULL | … |

| 1004 | NULL | NULL | NULL | … |

With 1M flights, 20 event columns:

- 20M total cells

- 19M NULLs (95%)

- Storage waste: Implementation-dependent, but significant

Semantic ambiguity:

- NULL = unknown?

- NULL = does not apply?

- NULL = not recorded?

Querying sparse data is awkward:

-- Find flights with delays NOT due to weather

SELECT * FROM flights

WHERE delay_reason IS NOT NULL

AND delay_reason != 'weather';

-- Flights with ANY special event

SELECT * FROM flights

WHERE delay_reason IS NOT NULL

OR diverted_airport IS NOT NULL

OR emergency_landing IS NOT NULL

OR passenger_medical IS NOT NULL

-- ...15 more conditionsSparse attributes common in:

- Event tracking

- Optional features

- User preferences

- Sensor readings

- Medical records

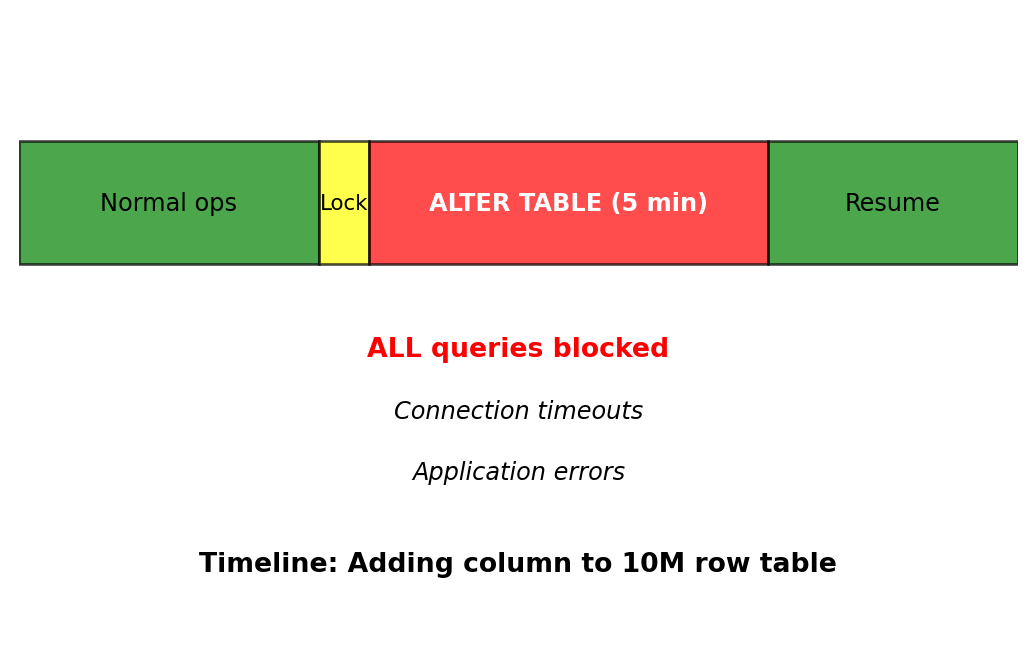

Schema Evolution Under Load

Need to add column to flights table with 10M rows:

PostgreSQL behavior:

- Acquires ACCESS EXCLUSIVE lock

- Blocks ALL reads and writes during operation

- On large tables: Minutes of downtime

- Application connections timeout and fail

Timing for different table sizes:

| Rows | ALTER TABLE time | Downtime |

|---|---|---|

| 10K | ~1 second | Acceptable |

| 100K | ~10 seconds | Problematic |

| 1M | ~30 seconds | Unacceptable |

| 10M | ~5 minutes | Critical |

Zero-downtime migration requires shadow table (complexity: high, time: hours)

Application-level workaround (complex):

- Create shadow table with new schema

- Implement dual-write to both tables

- Backfill old data to new table

- Switch application to new table

- Drop old table

Error-prone:

- Maintaining data consistency during migration

- Coordinating application deployments

- Rollback strategy if issues arise

Relational Remains Correct for Structured Data

Flight operations data FITS relational well:

Uniform schema:

- Every flight has same structure

- Every booking follows same pattern

- Every passenger has consistent attributes

Clear relationships:

- Foreign keys model real entities

- Referential integrity enforced by database

- JOIN operations match conceptual relationships

Transaction requirements:

- Booking seat → decrease inventory atomically

- Payment + confirmation must succeed together

- ACID properties critical for correctness

Known queries:

- Predictable access patterns

- Standard reporting needs

- Queries match table structure

-- These queries are natural and efficient

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM bookings WHERE flight_id = 1234;

SELECT f.*, COUNT(b.booking_id) as passenger_count

FROM flights f

LEFT JOIN bookings b ON f.flight_id = b.flight_id

GROUP BY f.flight_id;

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

INSERT INTO bookings (passenger_id, flight_id, seat)

VALUES (123, 456, '12A');

UPDATE flights SET available_seats = available_seats - 1

WHERE flight_id = 456;

COMMIT;If your data looks like this, relational is the correct choice

When relational is correct:

- Uniform schema per entity type

- Relationships map to foreign keys

- ACID transactions required

- Queries match table structure

- Data integrity constraints needed

When to consider alternatives:

- Variable attributes per entity

- Deep object hierarchies

- Sparse/optional attributes

- Graph traversal queries

- Frequent schema changes

Match data structure to model — not every problem needs NoSQL

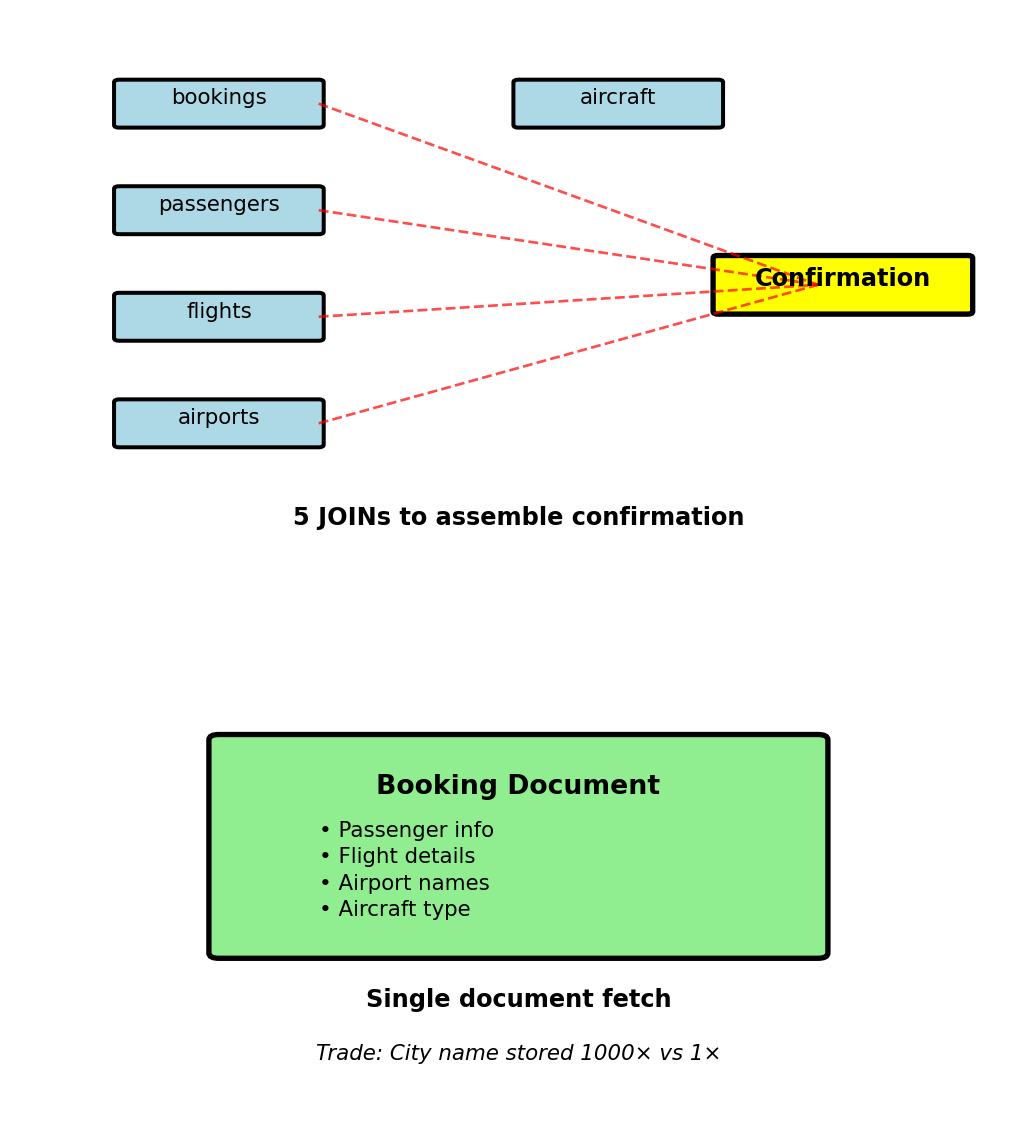

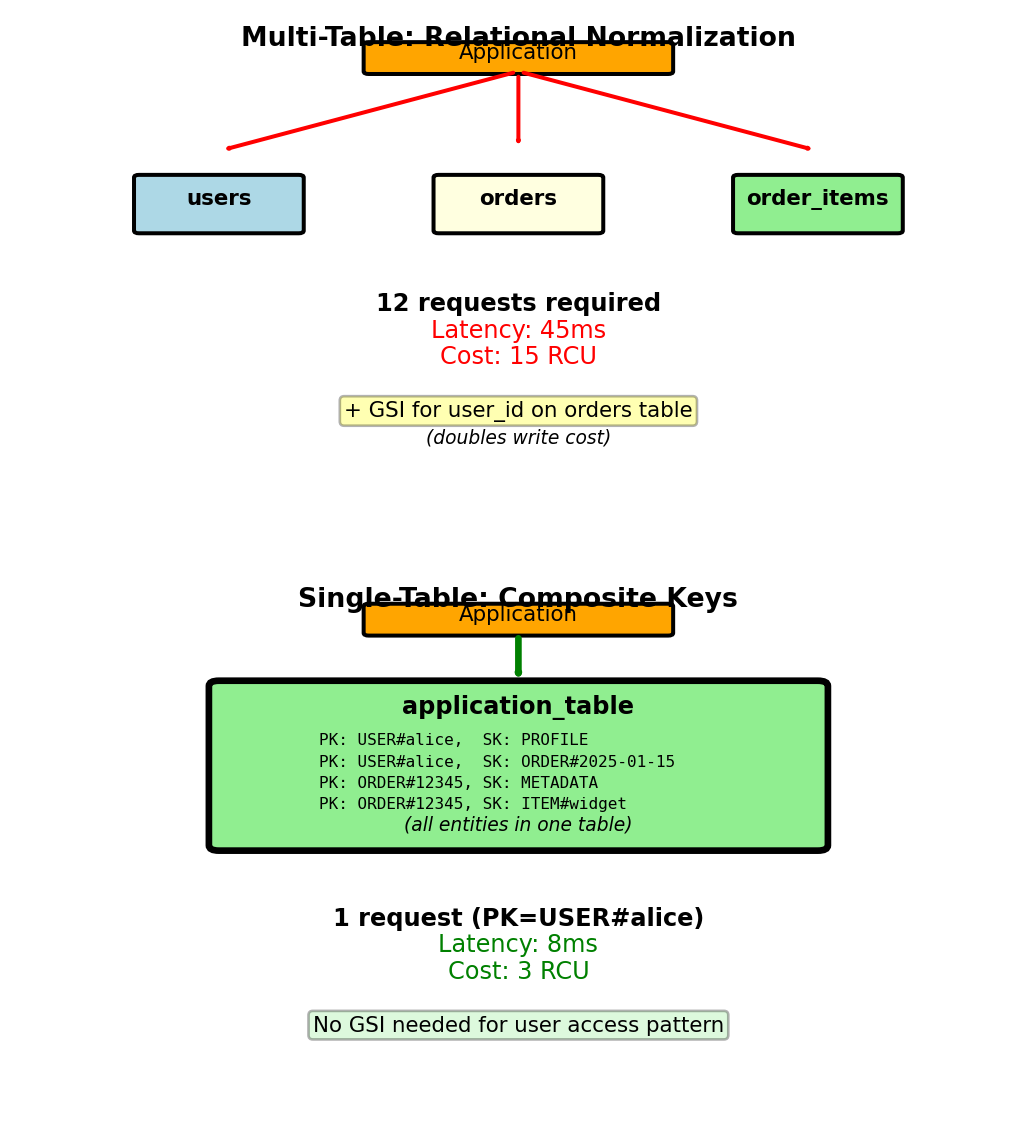

Query Patterns Define Data Model

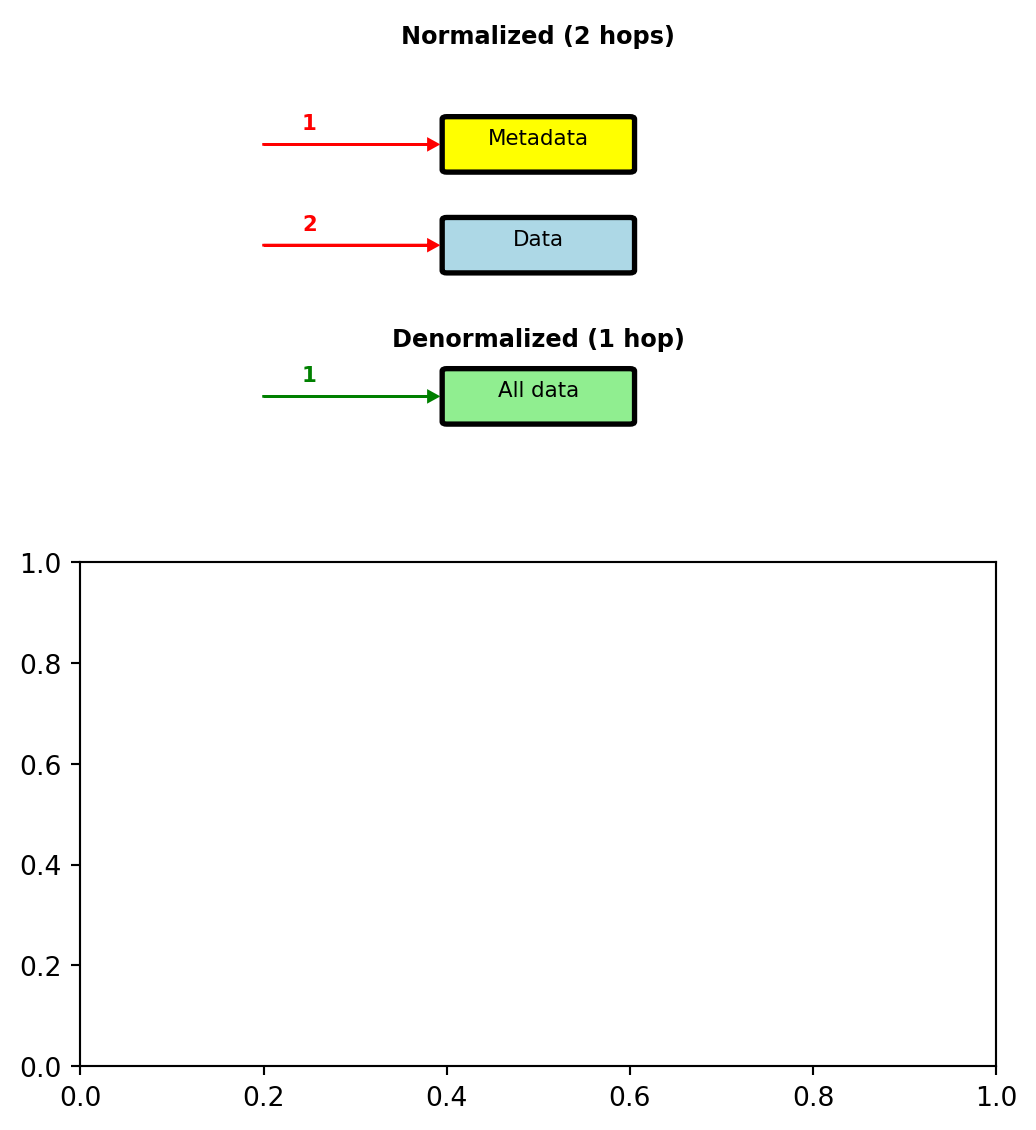

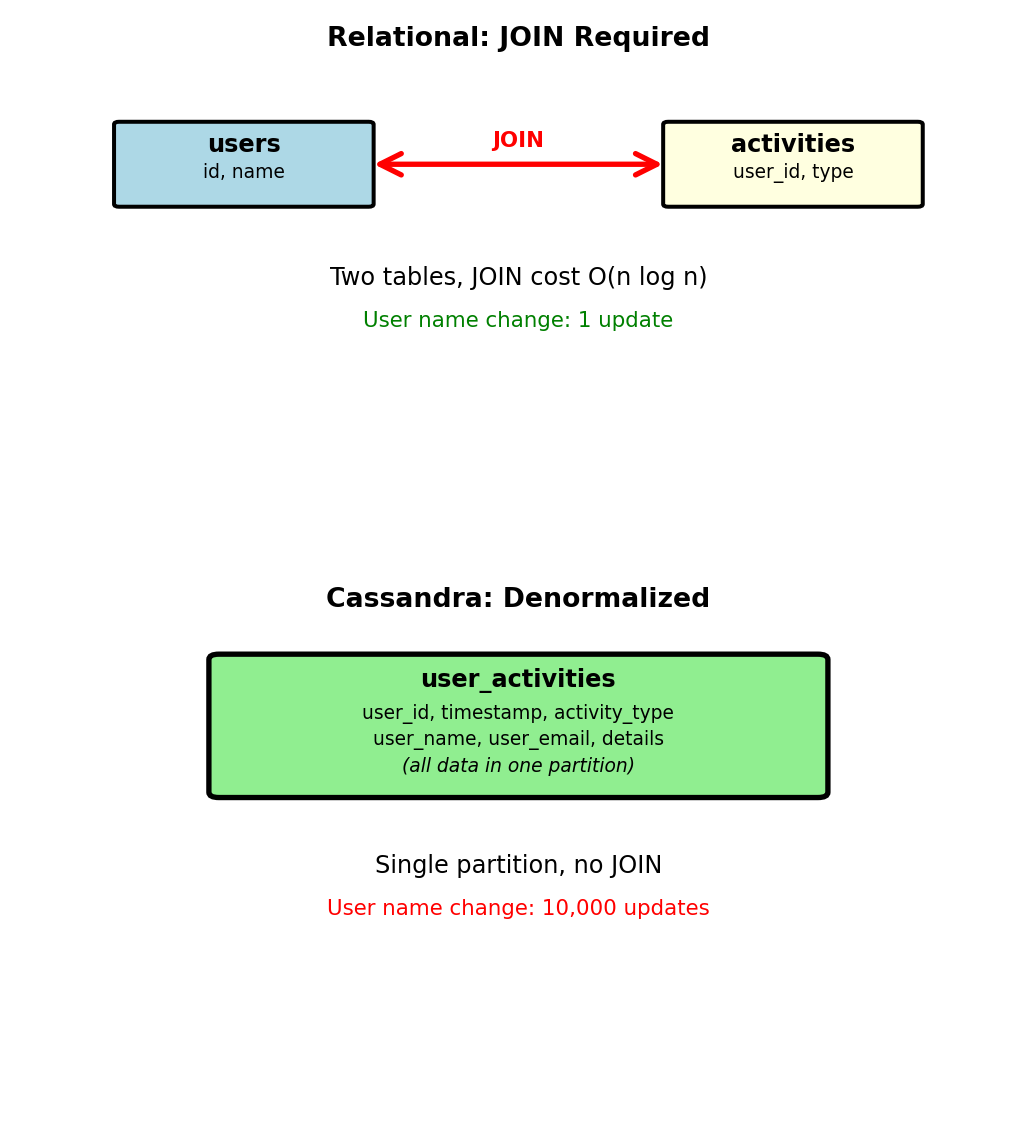

Relational Normalizes, NoSQL Denormalizes

Relational modeling:

- Normalize to 3NF, eliminate redundancy

- Single source of truth for each fact

- JOIN to assemble complete views

NoSQL modeling:

- Start with queries, store data for read patterns

- Redundancy acceptable for query performance

- Trade storage and update complexity for read simplicity

Example: Flight booking confirmation email

Relational approach: JOIN 5 tables

SELECT b.booking_reference, p.name, p.email,

f.flight_number, f.scheduled_departure,

d.name AS departure_city,

a.name AS arrival_city,

ac.model AS aircraft_type

FROM bookings b

JOIN passengers p ON b.passenger_id = p.passenger_id

JOIN flights f ON b.flight_id = f.flight_id

JOIN airports d ON f.departure_airport = d.airport_code

JOIN airports a ON f.arrival_airport = a.airport_code

JOIN aircraft ac ON f.aircraft_id = ac.aircraft_id

WHERE b.booking_id = 12345;NoSQL approach: Store complete confirmation in booking document

Update cost: User name changes → update in 1000 places vs 1 place

When acceptable: Reads >> Writes (confirmation viewed 100× more than user changes name)

Access Pattern - Flight Status Display

Requirement: Airport display showing flight status

- Refreshes every 30 seconds

- Shows next 2 hours of departures

- 100 displays at LAX

Query: “All departures from LAX in next 2 hours”

Data needed:

- Flight number, gate, status

- Destination city name (not just code)

- Aircraft type

- Departure time

Relational approach:

SELECT f.flight_number, f.gate, f.status,

f.scheduled_departure,

a.model AS aircraft_type,

ap.name AS destination_city

FROM flights f

JOIN aircraft a ON f.aircraft_id = a.aircraft_id

JOIN airports ap ON f.arrival_airport = ap.airport_code

WHERE f.departure_airport = 'LAX'

AND f.scheduled_departure BETWEEN NOW()

AND NOW() + INTERVAL '2 hours';Frequency analysis:

- 100 displays × 120 queries/hour = 12,000 queries/hour

- Schedule changes: ~5 updates/hour

- Read:Write ratio = 2400:1

NoSQL approach: Denormalize for display query

Single query, no joins:

Read:Write ratio 2400:1 justifies denormalization

Aircraft model duplicated in every flight using that aircraft

City name duplicated in every flight to that destination

Updates rare, reads constant

Embedding - Passenger Special Services

Earlier Problem: Variable passenger services

- Wheelchair assistance

- Meal preferences

- Pet carrier

- Varying per passenger

Document approach: Embed services as nested object

{

"passenger_id": 123,

"name": "Alice Chen",

"email": "alice@example.com",

"phone": "+1-555-0123",

"services": {

"wheelchair": true,

"meal": "vegetarian",

"pet_carrier": true,

"seat_preference": "aisle",

"medical_oxygen": false

},

"frequent_flyer": {

"number": "FF123456",

"tier": "Gold",

"miles": 85000

}

}Why embed:

- Accessed together in primary query pattern

- Small size (<1KB total)

- No independent existence

- Services have no meaning without passenger context

Single document fetch gets everything

No NULL columns for passengers without services

Store only what exists, no wasted NULL storage

Referencing - Flight Bookings

Flight with 200 bookings - cannot embed all:

Size problem:

- 200 bookings × 1KB each = 200KB

- MongoDB limit: 16MB

- DynamoDB limit: 400KB

- Approaching limits with just bookings

Access problem:

- Fetching flight details does not need all bookings

- Display shows “seats available”, not passenger list

- Loading 200KB when 1KB needed

Update problem:

- Every new booking rewrites entire flight document

- Concurrent booking updates conflict

- Document-level locking affects all bookings

Solution: Reference pattern

// Flight document (small, frequently accessed)

{

"flight_id": 456,

"flight_number": "UA123",

"departure_airport": "LAX",

"arrival_airport": "JFK",

"scheduled_departure": "2025-02-15T14:30:00Z",

"seats_available": 12,

"total_seats": 180

}

// Booking document (separate collection)

{

"booking_id": 789,

"flight_id": 456, // Reference to flight

"passenger_id": 123,

"seat": "12A",

"booking_time": "2025-01-15T10:30:00Z"

}Query patterns:

Get flight details:

Get bookings for flight:

Add new booking:

Trade-off:

- Embedded: 200 KB document (grows with bookings)

- Referenced: 1 KB flight + 1 KB per booking (separate queries)

- Document size limit: 16 MB (MongoDB)

Like foreign keys, but application-enforced (not database engine!)

Sensor Data at Scale - Distribution Patterns

Scenario: IoT temperature sensor network

- 100,000 sensors

- 1 reading per minute per sensor

- 5 years retention required

Data volume:

- 100K sensors × 60 readings/hour = 6M readings/hour

- 144M readings/day

- 52.6B readings/year

- 5 years = 263B readings

Cannot fit on single server:

- 263B readings × 50 bytes/reading = 13TB

- Query latency unacceptable on 13TB

- Write throughput: 1,667 writes/second continuous

Read patterns:

- Recent readings for one sensor (95% of queries)

- “Sensor 42000 last 24 hours”

- All readings for sensor in time range (4%)

- “Sensor 42000 January 2025”

- Average across all sensors (1%)

- “Average temperature now”

Distribution required: 13TB cannot fit on single server

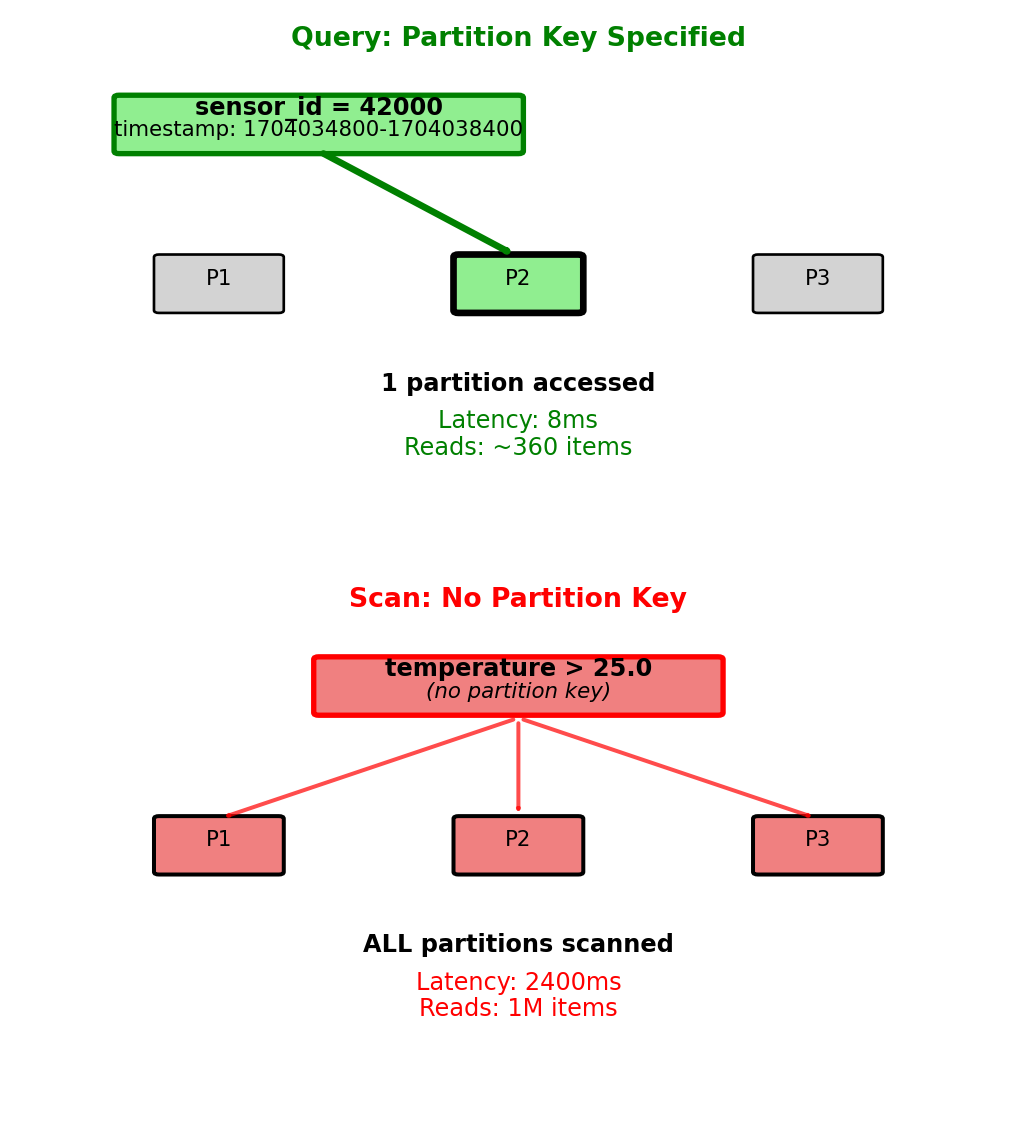

Partition strategy determines query efficiency:

- Primary pattern: Single sensor queries (99%)

- Rare pattern: Cross-sensor aggregation (1%)

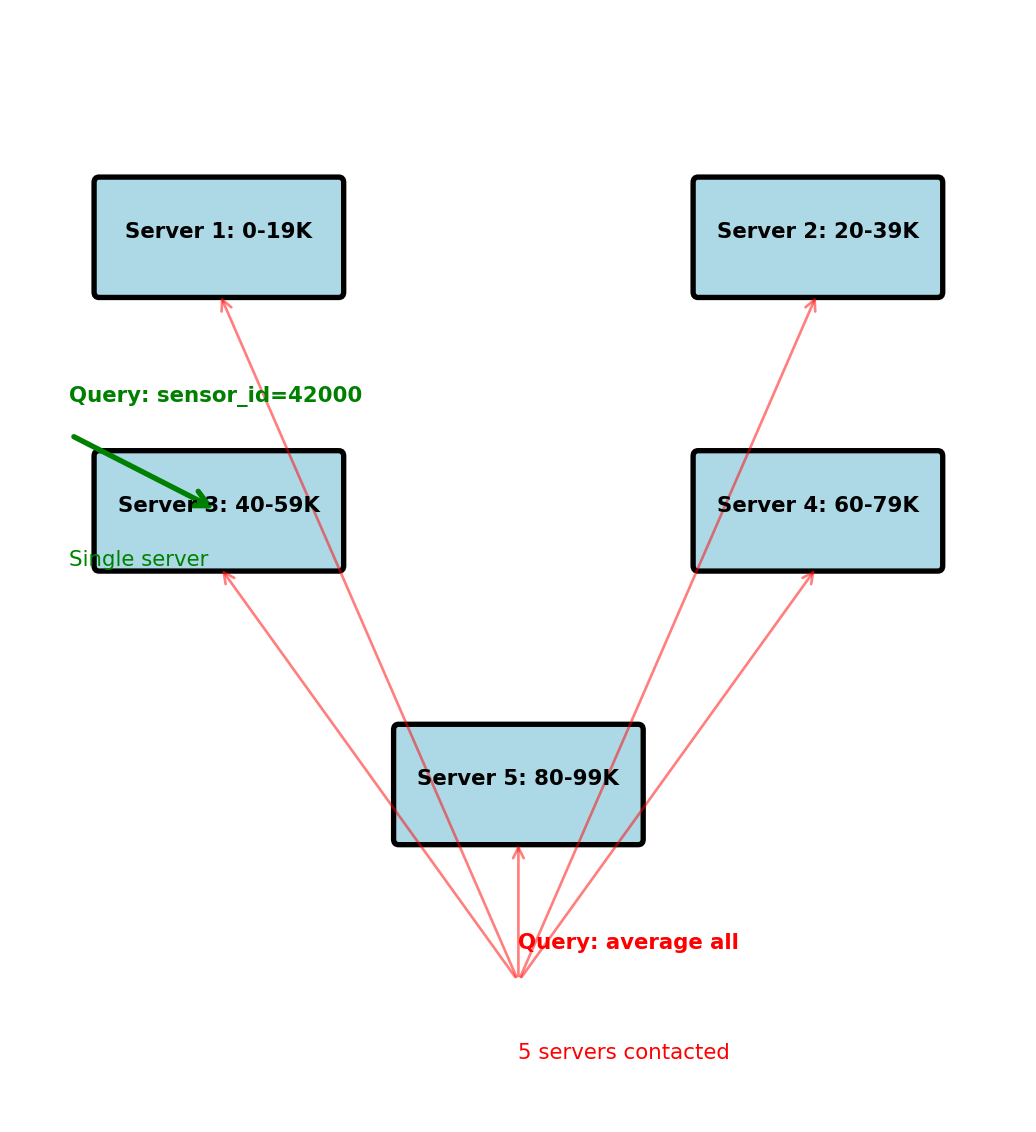

Sensor Data - Partition by Sensor ID

Partition strategy: All data for sensor_id on same server

Physical layout across 5 servers:

- Server 1: sensor_id 0-19,999 (20K sensors)

- Server 2: sensor_id 20,000-39,999

- Server 3: sensor_id 40,000-59,999

- Server 4: sensor_id 60,000-79,999

- Server 5: sensor_id 80,000-99,999

Each server stores:

sensor_id | timestamp | temperature

----------|--------------------|-----------

40000 | 2025-01-15 00:00 | 21.0

40000 | 2025-01-15 00:01 | 21.1

40000 | 2025-01-15 00:02 | 21.2

...

40001 | 2025-01-15 00:00 | 19.5Query 1: “Sensor 42000, last 24 hours”

- Hash(42000) → Server 3

- Route query to single server

- Single server processes query

- Fast: O(1) routing, O(log n) within server

Query 2: “Average temperature all sensors”

- Must contact all 5 servers

- Each computes local average

- Coordinator aggregates results

- Slow: 5× network calls

Performance:

- Single sensor query: ~5ms

- All sensors query: ~50ms (parallel) + aggregation

Partition key determines query efficiency

Sensor Data - Row Structure Optimized for Queries

Query requirement: Readings with metadata

- Location where sensor installed

- Sensor type and calibration info

- Building/floor information

Relational approach (bad for distributed):

-- Metadata on central server

CREATE TABLE sensors (

sensor_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

location VARCHAR(100),

building VARCHAR(50),

sensor_type VARCHAR(20)

);

-- Readings partitioned across 5 servers

CREATE TABLE readings (

sensor_id INT,

timestamp TIMESTAMP,

temperature FLOAT,

FOREIGN KEY (sensor_id) REFERENCES sensors

);Query needs metadata:

- Fetch metadata from central server

- Fetch readings from data server

- Join in application = 2 network round-trips

Denormalized approach:

Storage trade-off:

- +40 bytes per reading (metadata)

- 263B readings × 40 bytes = 10.5TB extra

- Total: 23.5TB vs 13TB

Query performance:

Query performance:

- Normalized: 25ms (2 server roundtrips)

- Denormalized: 5ms (single server)

Update frequency:

- Sensor location changes: ~1 per month

- Temperature readings: 100K per minute

Denormalization justified by read:write ratio

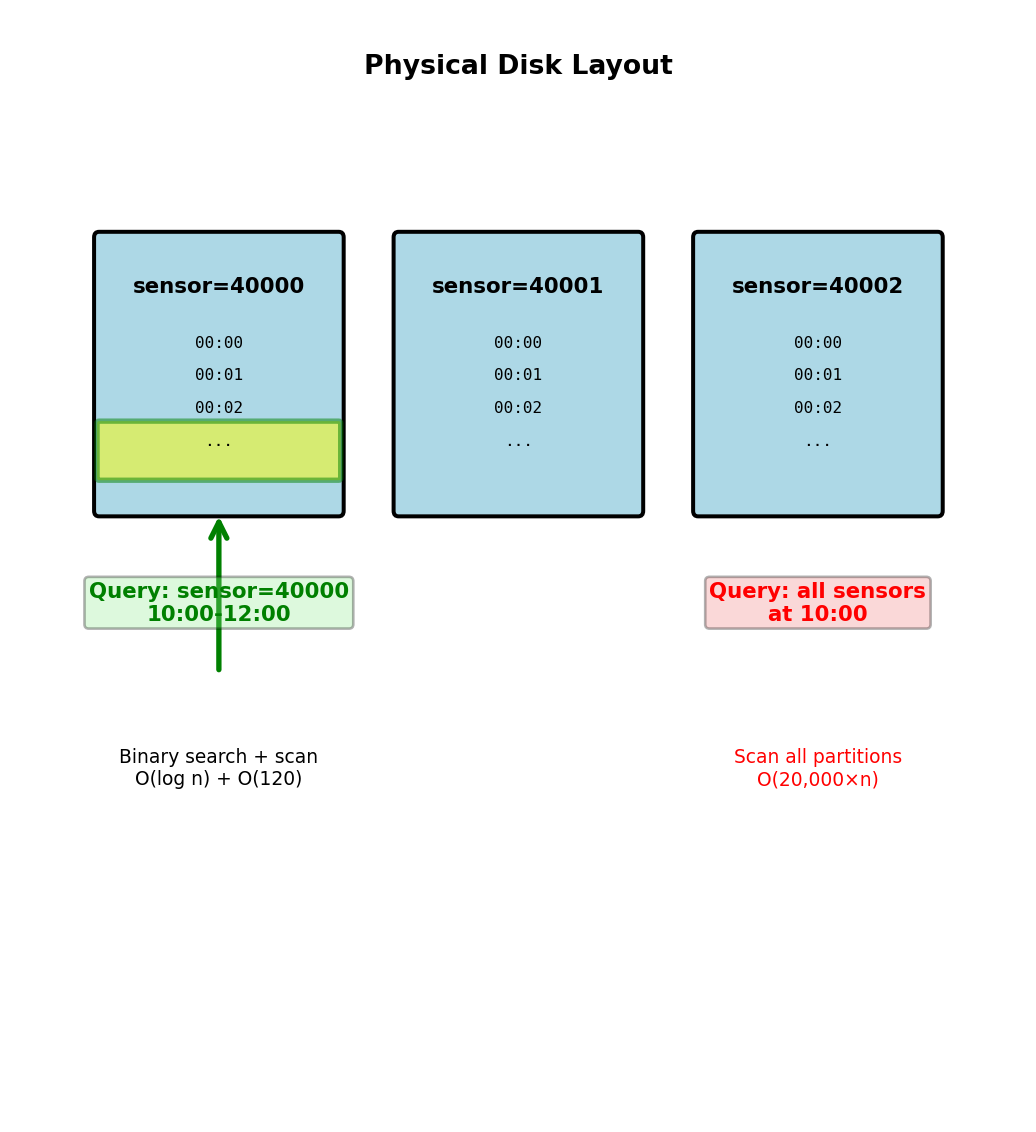

Sensor Data - Compound Sort Key for Time Queries

Data on Server 3 (sensor_id 40,000-59,999):

- Primary: Partition by sensor_id

- Secondary: Sort by timestamp within partition

Physical layout on disk:

Partition: sensor_id=40000

--------------------------

timestamp | temp

2025-01-15 00:00:00 | 21.0

2025-01-15 00:01:00 | 21.1

2025-01-15 00:02:00 | 21.2

...

2025-01-15 23:59:00 | 20.8

Partition: sensor_id=40001

--------------------------

timestamp | temp

2025-01-15 00:00:00 | 19.5

2025-01-15 00:01:00 | 19.6

...Query: “sensor_id=40000 between 10:00 and 12:00”

- Hash(40000) → locate partition

- Binary search to find 10:00:00

- Sequential scan until 12:00:00

- Return ~120 readings

Efficient: O(log n) + O(k) where k = result size

Cannot efficiently query: “All sensors at 10:00”

- Would scan all 20,000 partitions on this server

- Then contact other 4 servers

- Query pattern not supported by layout

Sort order within partition provides O(log n) range queries

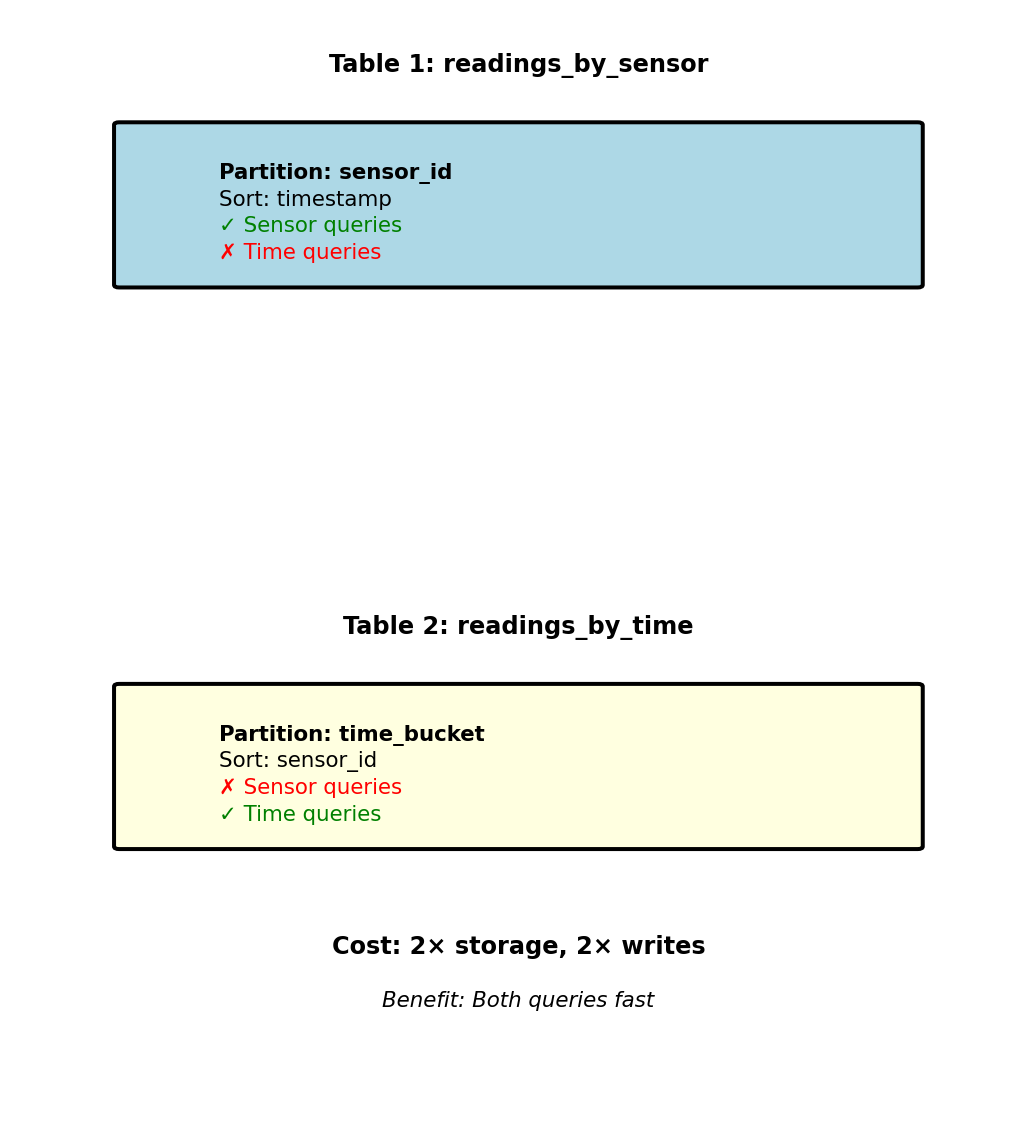

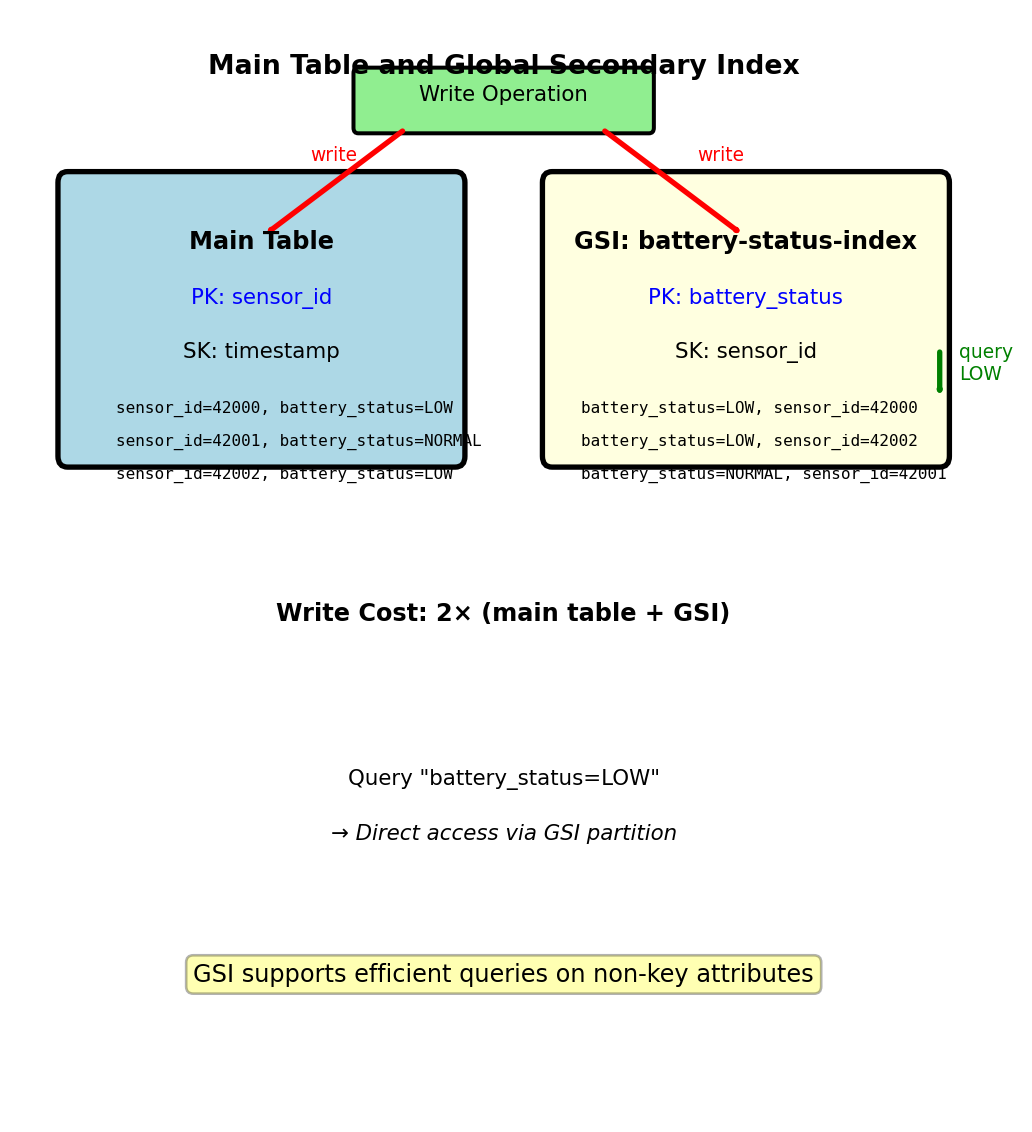

Multiple Access Patterns Require Multiple Tables

Two different access patterns:

Pattern 1: Recent readings by sensor

- “Get sensor 42000 for last 24 hours”

- Need: Partition by sensor_id, sort by timestamp

Pattern 2: All sensors at specific time

- “Get all sensors at 10:00-11:00”

- Need: Partition by timestamp, sort by sensor_id

Same data, stored twice:

-- Table 1: Optimized for sensor queries

CREATE TABLE readings_by_sensor (

sensor_id INT, -- Partition key

timestamp TIMESTAMP, -- Sort key

temperature FLOAT,

location TEXT,

PRIMARY KEY (sensor_id, timestamp)

);

-- Table 2: Optimized for time queries

CREATE TABLE readings_by_time (

time_bucket INT, -- Partition key (hour)

sensor_id INT, -- Sort key

temperature FLOAT,

location TEXT,

PRIMARY KEY (time_bucket, sensor_id)

);Write path: Application writes to both tables

Read path: Query router chooses table based on pattern

Cannot optimize single table for both patterns

Trade storage and write complexity for query performance

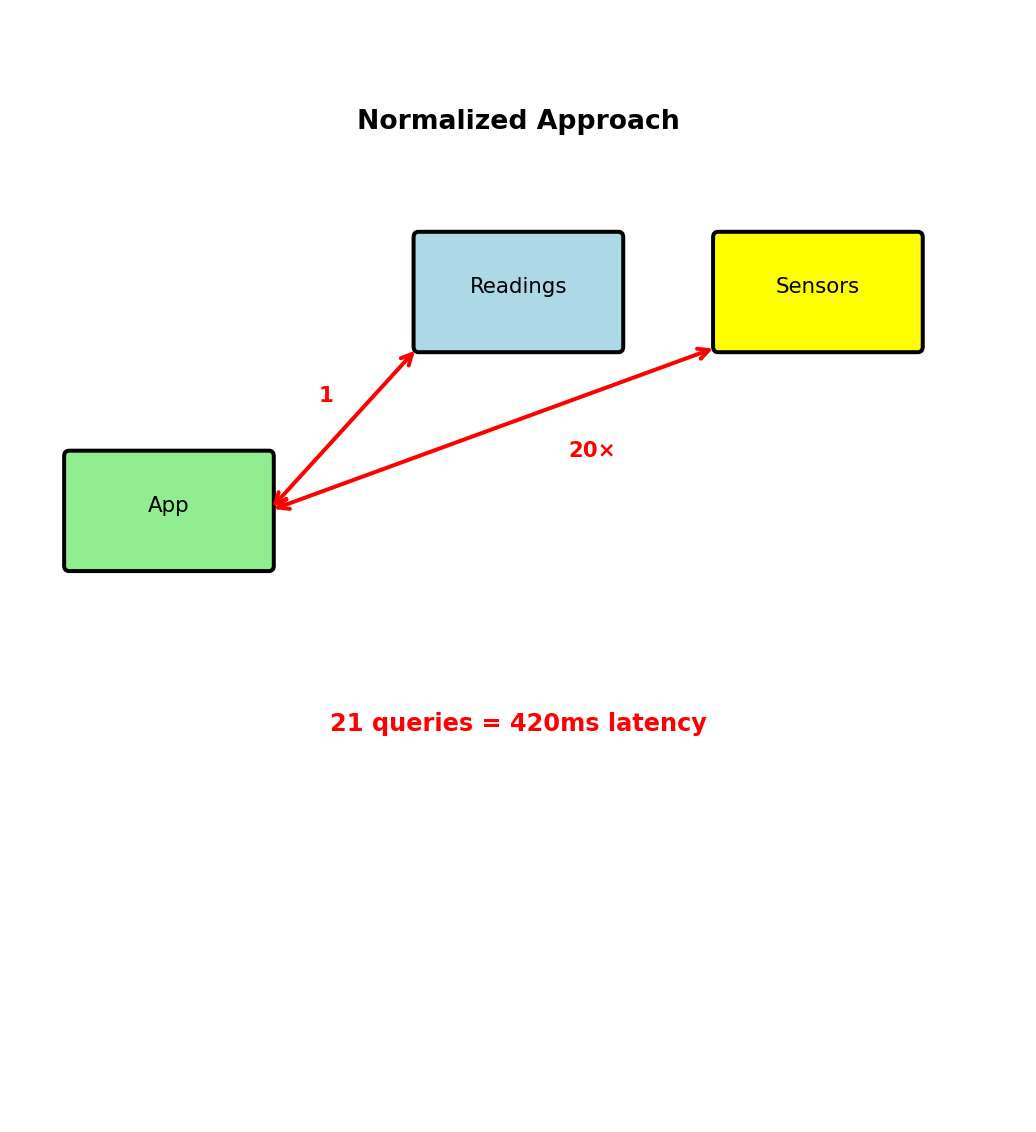

NoSQL Data Modeling Anti-Pattern - Relational Thinking

Anti-pattern: Normalize sensor data

// Sensors collection (metadata)

{

"sensor_id": 42000,

"location": "Building A, Floor 3",

"sensor_type": "indoor_temp",

"calibration_date": "2024-01-15"

}

// Readings collection (data)

{

"reading_id": 999999,

"sensor_id": 42000, // Reference

"timestamp": "2025-01-15T10:30:00Z",

"temperature": 22.5

}Query to display dashboard (100 recent readings):

- Fetch 100 readings from readings collection

- Extract unique sensor_ids

- Fetch sensor metadata for each unique sensor

- Join in application

Problem:

- 100 readings from 20 sensors = 21 queries

- Network latency: 20ms × 21 = 420ms

- Dashboard refresh every second? Impossible

Correct approach: Denormalize

- Store location with every reading

- Single query returns everything

- Latency: 20ms total (21× faster)

Relational normalization creates N+1 query problem

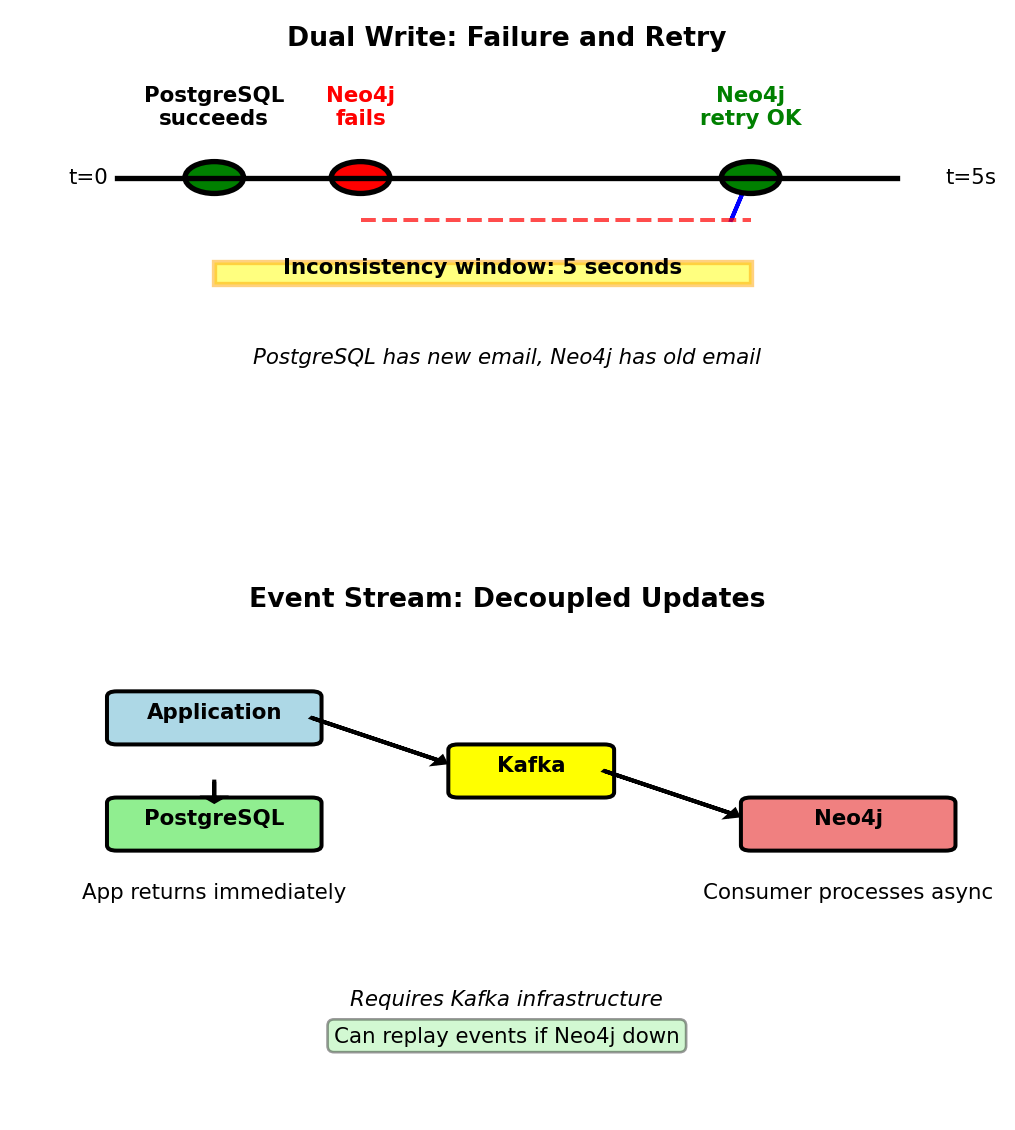

When Denormalization Breaks - Update Anomalies

Scenario: Sensor relocated (Building A → Building B)

With denormalization, location stored in:

- 1,440 readings per day (every minute)

- 43,200 readings per month

- 518,400 readings per year

Update options:

Option 1: Update all historical records

- 518,400 documents updated

- Takes minutes on distributed system

- Blocks other operations

- Historical data now incorrect

Option 2: Update going forward only

- Historical: “Building A”

- Current: “Building B”

- Query results inconsistent

- Acceptable for time-series

Option 3: Versioned metadata

More complex queries, additional lookup

When denormalization acceptable:

- Read:Write > 100:1

- Updates rare (monthly)

- Eventual consistency OK

- Historical accuracy not critical

When to avoid:

- Frequent updates (prices change hourly)

- Strong consistency required (inventory)

- Write-heavy workloads

- Regulatory accuracy requirements

Trade-off: Read performance vs update complexity

Scaling and Distribution Trade-offs

Single Node Capacity Limits

PostgreSQL practical limits on single node:

- Connections: 10,000 concurrent (connection overhead)

- Queries: 100,000 queries/sec (CPU bound)

- Storage: ~2TB practical limit (vacuum, index maintenance)

- Single point of failure

Real production at scale:

Netflix streaming service:

- 230M subscribers

- 1% concurrent = 2.3M active users

- 10 requests/sec per user = 23M requests/sec

- Single node handles: 100K requests/sec

- Required: 230+ database nodes minimum

Reddit (2023):

- 14TB PostgreSQL database

- Schema migrations: 6 hours of downtime

- Read replicas: 50+ to handle read load

Single-machine limits: Cannot fit internet-scale workloads on one node

Single node limits:

| Resource | Limit | Bottleneck |

|---|---|---|

| Connections | 10K | Memory overhead |

| Queries/sec | 100K | CPU cores |

| Storage | 2TB | Vacuum time |

| Write throughput | 50K/sec | Disk I/O |

Capacity mismatch:

Example workload (social media):

- 100M users

- 5% active concurrently = 5M

- 5 queries/user/sec = 25M queries/sec

Single PostgreSQL node: 100K queries/sec

Gap: 250× capacity needed

Cannot be solved with bigger hardware — must distribute across multiple nodes

Vertical vs Horizontal Scaling Economics

Vertical scaling = bigger machine:

AWS RDS pricing (2024):

- 128GB RAM: $1,380/month → $10.78/GB

- 1TB RAM: $11,040/month → $10.78/GB

- 4TB RAM: $38,880/month → $9.72/GB

- 8TB RAM: $77,760/month → $9.72/GB

Capacity scaling:

- 10× data requires 10× RAM

- 10× queries requires 10× CPU

- But: 10× cost gets 10× capacity (best case)

Problems with vertical:

- Single point of failure

- Limited by hardware (8TB RAM max)

- Downtime for upgrades

- Cannot add capacity gradually

At Reddit’s 14TB:

- No single machine available

- Must distribute anyway

Horizontal scaling = more machines:

10 nodes × 128GB RAM:

- Capacity: 1.28TB total

- Cost: 10 × $1,380 = $13,800/month

- Redundancy: Lose 1 node, still operational

- Incremental: Add nodes as needed

Comparison for 1TB capacity:

| Approach | Configuration | Cost | Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical | 1 × 1TB | $11,040 | None |

| Horizontal | 10 × 128GB | $13,800 | 9 nodes survive failure |

Horizontal advantages:

- Linear cost scaling

- Built-in redundancy

- No single point of failure

- Add capacity without downtime

Trade-off: Horizontal requires distributing data and coordinating across nodes

Partitioning Splits Data Across Nodes

Partition = subset of data assigned to one node

Example: 10M users, 10 nodes

- Each node stores 1M users

- Query routes to node containing requested data

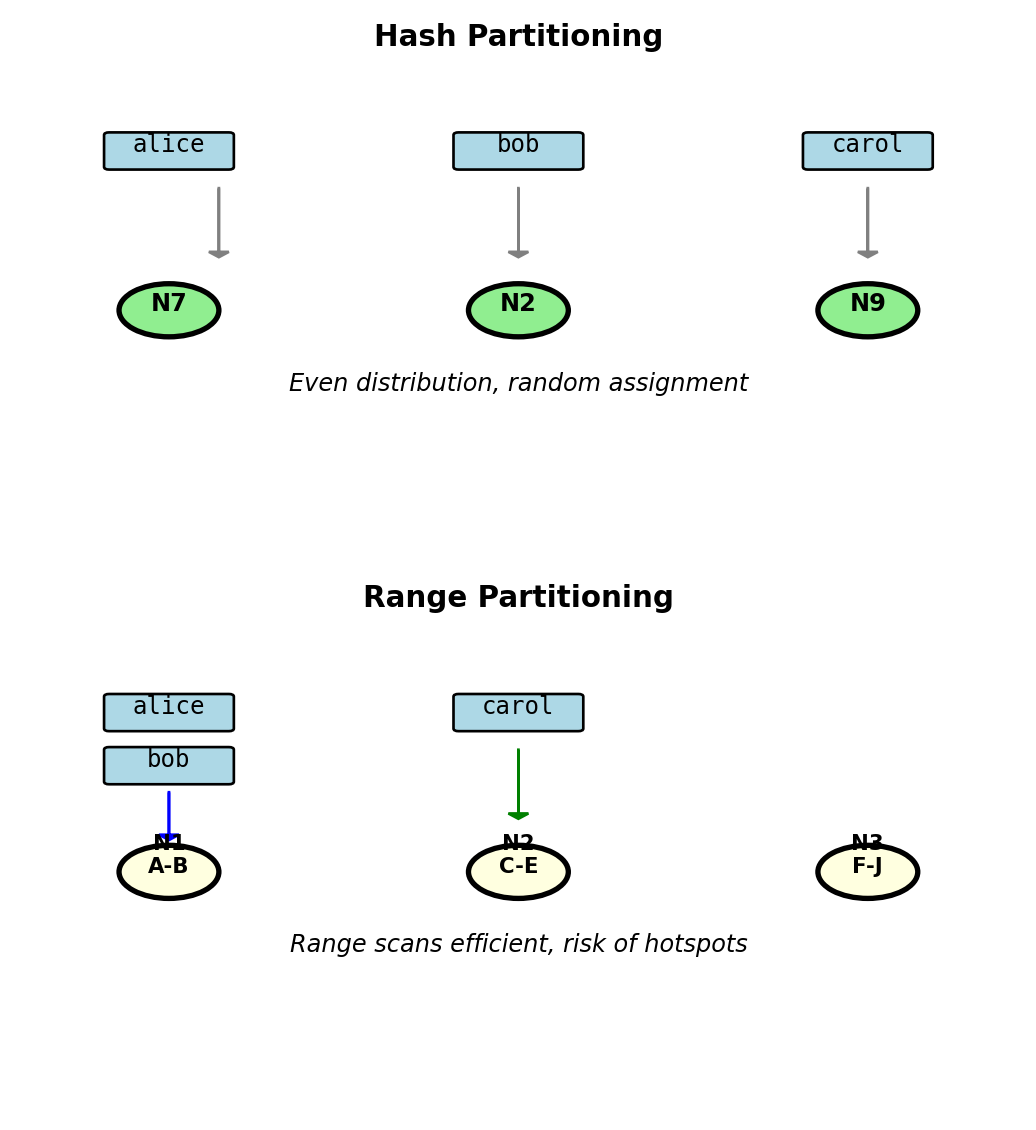

Two partitioning strategies:

Hash-based partitioning:

Characteristics:

- Even distribution (no hotspots)

- Random assignment

- Range queries scan all nodes

Range-based partitioning:

A-B → Node 1

C-E → Node 2

F-J → Node 3

...

Z → Node 10

"alice" → Node 1

"bob" → Node 1

"carol" → Node 2Characteristics:

- Range scans stay on few nodes

- Risk: Hotspots if data skewed

Trade-off: Even load vs efficient range queries

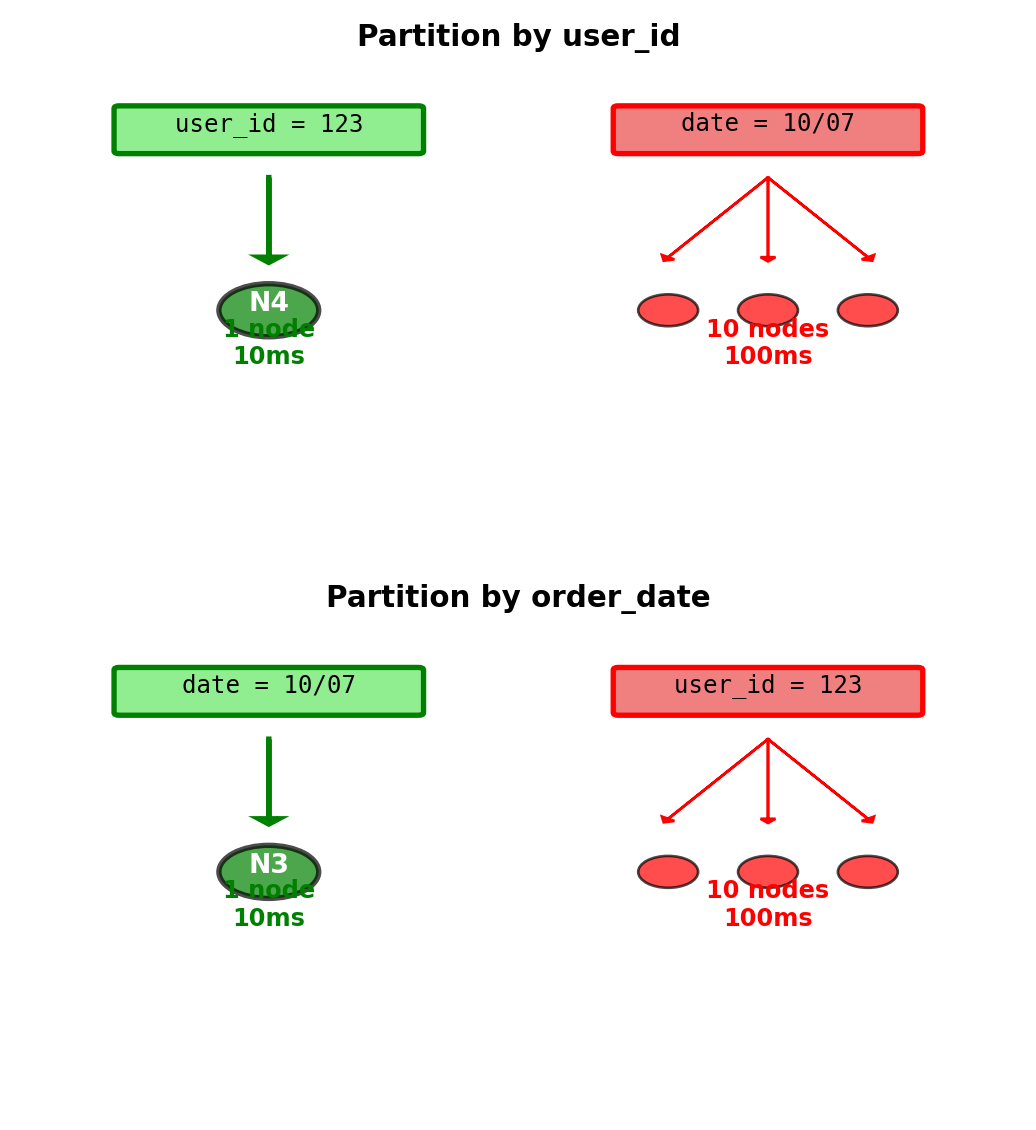

Partition Key Determines Data Location and Query Routing

Partition key = attribute used to determine node assignment

Example: E-commerce orders table

Option 1: Partition by user_id

Option 2: Partition by order_date

Partition key choice optimizes one access pattern at expense of others

Cost of wrong choice:

- Single-node query: 10ms latency

- Cross-partition query: 10 nodes × 10ms = 100ms latency

- Plus: Network coordination overhead

Partition key choice determines which queries are efficient

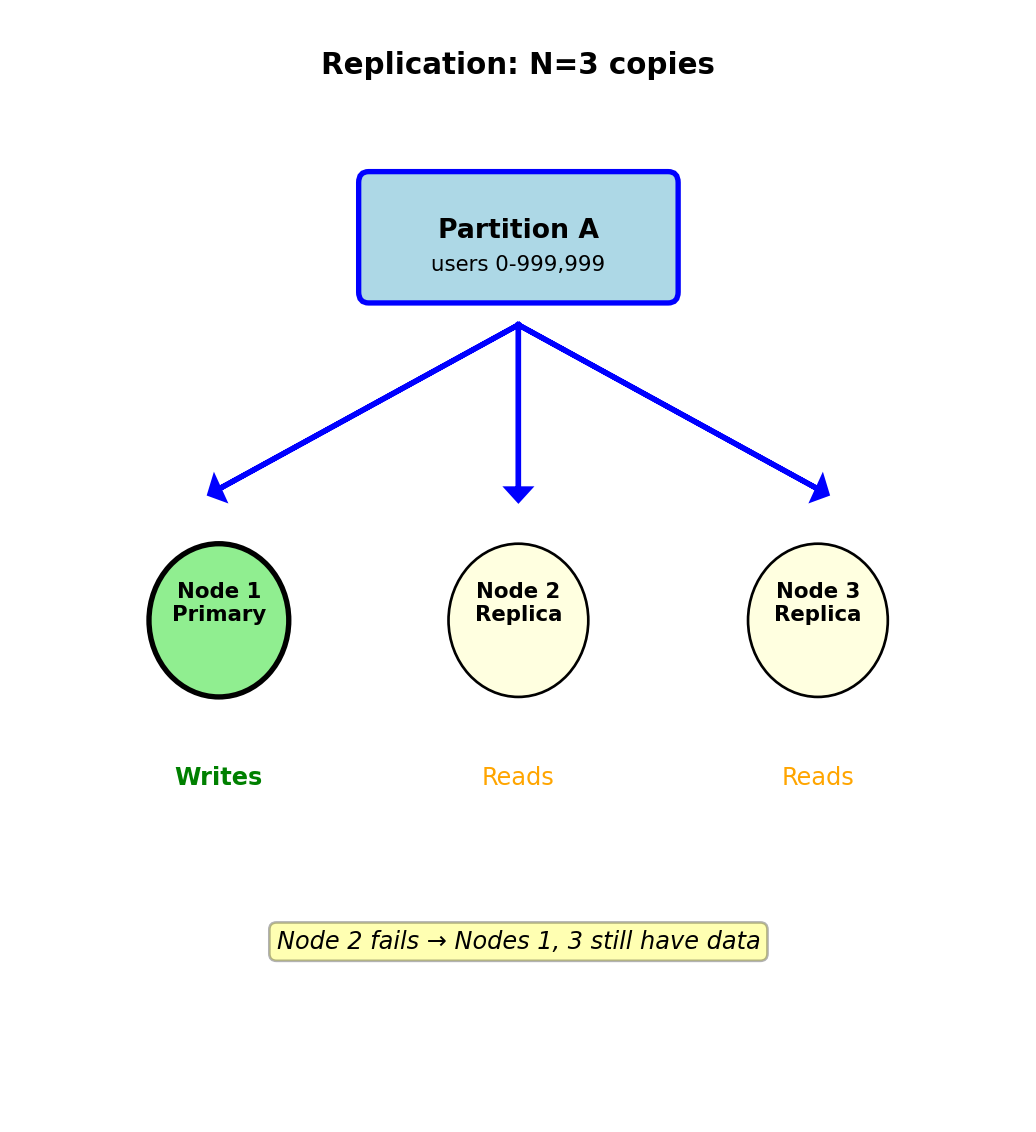

Replication Provides Redundancy

Replication = store multiple copies of data on different nodes

Why replicate:

1. Fault tolerance:

- Disk failure: 0.5% annual failure rate

- With 100 nodes: Expect 1 failure every 2 months

- Without replication: Data loss

- With 3 replicas: 2 copies survive

2. Read scaling:

- Primary handles writes

- Replicas handle reads

- 3 replicas = 3× read capacity

3. Geographic distribution:

- US datacenter + EU datacenter + Asia datacenter

- Place replica near users: 10ms vs 200ms latency

Standard configuration: N=3 replicas

Example: Partition A (users 0-999,999)

- Primary: Node 1 (handles writes)

- Replica 1: Node 2 (handles reads)

- Replica 2: Node 3 (handles reads)

Storage cost: 3× disk space

3 replicas = survive 2 simultaneous failures

Replication Creates Consistency Problem

Write must propagate from primary to replicas

Write flow:

- Client sends write to Primary (Node 1)

- Primary updates local copy

- Primary sends update to Replicas (Nodes 2, 3)

- Replicas acknowledge receipt

Network latencies:

- Same datacenter: 1-5ms between nodes

- Cross-datacenter: 50-200ms

- Replica may be temporarily offline

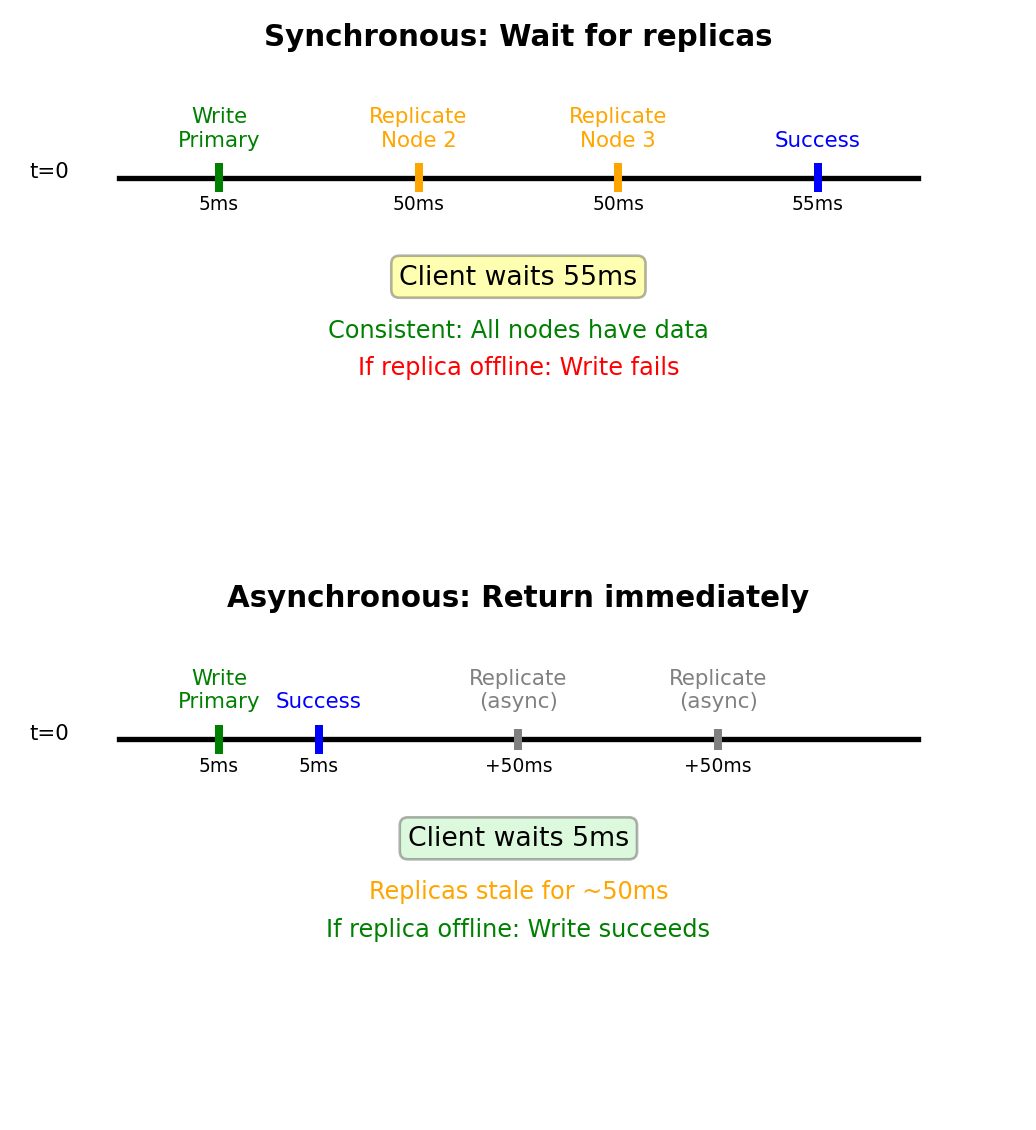

Critical question: When does write “succeed”?

Option A: Wait for all replicas (synchronous)

Client → Primary (5ms) → Wait for replicas (50ms)

Total latency: 55ms

If replica offline: Write fails

Result: All nodes have same data (consistent)Option B: Return immediately (asynchronous)

Client → Primary (5ms) → Return success

Replicas updated in background (async)

Total latency: 5ms

If replica offline: Write still succeeds

Result: Replicas temporarily stale (inconsistent)Trade-off: 5ms vs 55ms response time

Consistency vs latency vs availability trade-off

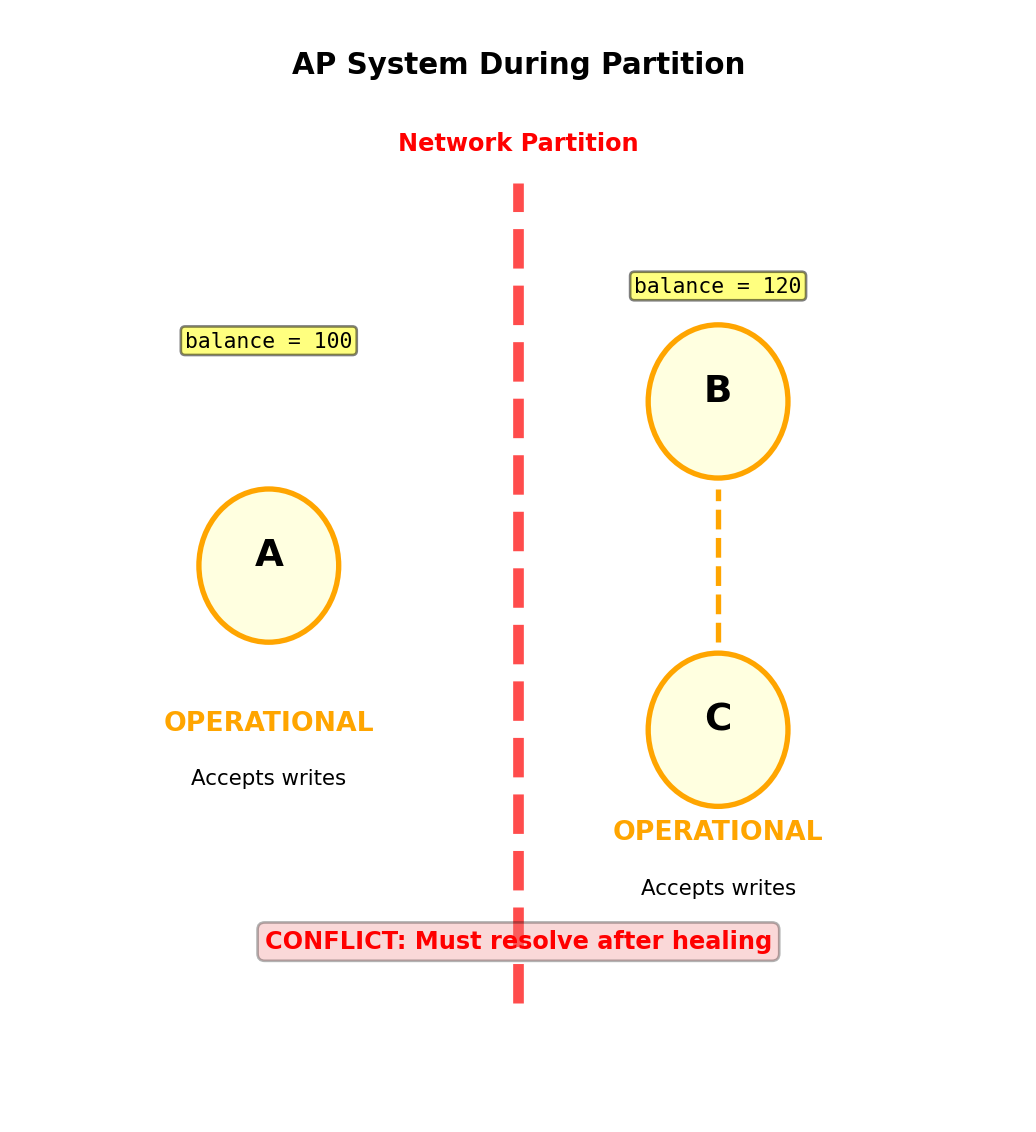

Network Partitions Split Clusters

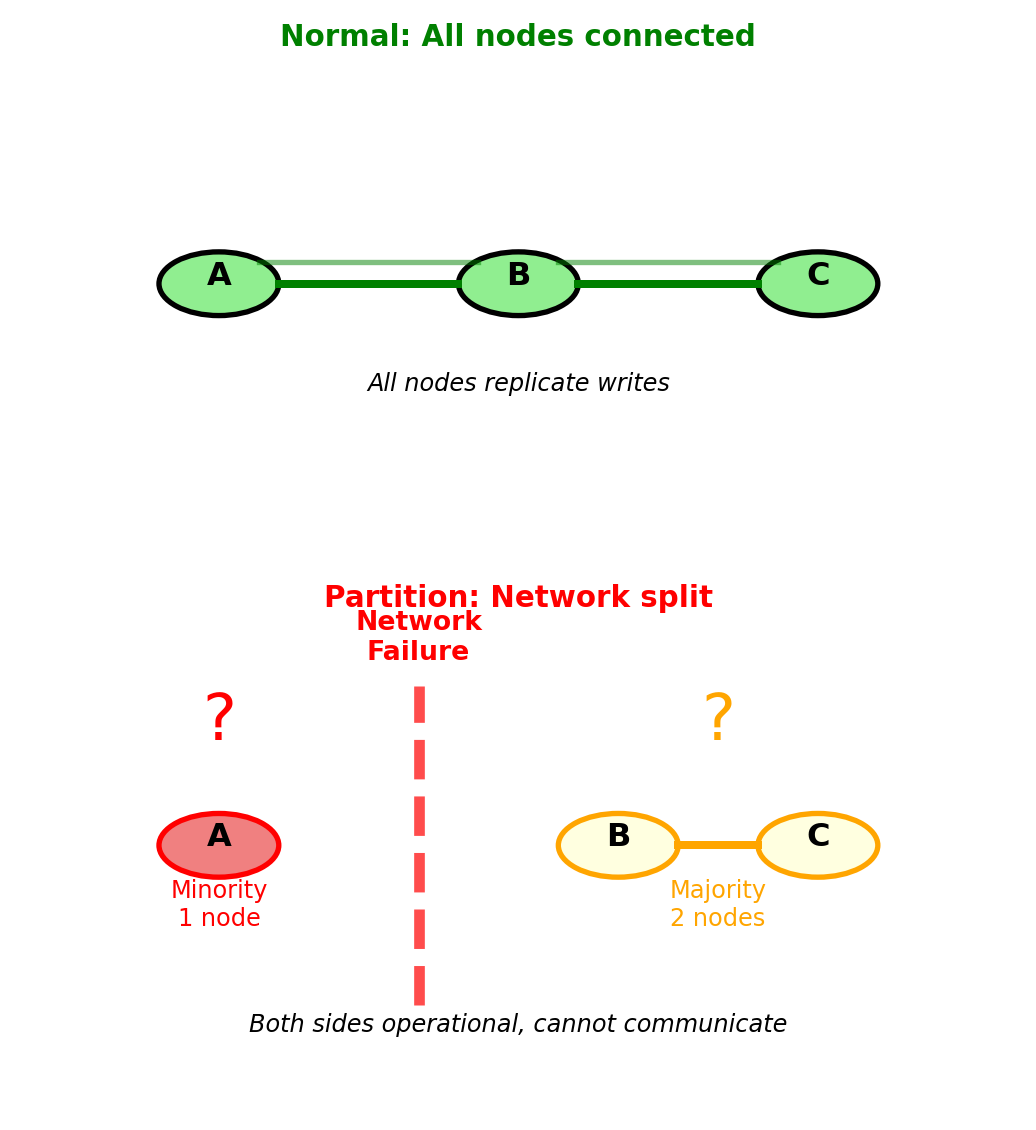

Network partition = nodes cannot communicate due to network failure

Common causes:

- Switch failure in datacenter

- Fiber cable cut (construction accident)

- Network misconfiguration

- AWS documented frequency: ~0.1% of requests see partition effects

Example: 3-node cluster [A, B, C]

Normal operation:

- All nodes communicate

- Writes propagate A → B → C

Network partition occurs:

- Network splits: [Node A] isolated from [Nodes B, C]

- Both sides still operational

- Both sides think they’re correct

Critical problem: Neither side knows if other side crashed or network failed

Duration:

- Seconds: Brief network glitch

- Minutes: Switch reboot

- Hours: Waiting for human intervention (fiber repair)

During partition:

- Both sides may accept writes

- Creates conflicting data versions

- Must resolve after partition heals

Partition forces choice: reject writes or accept conflicts

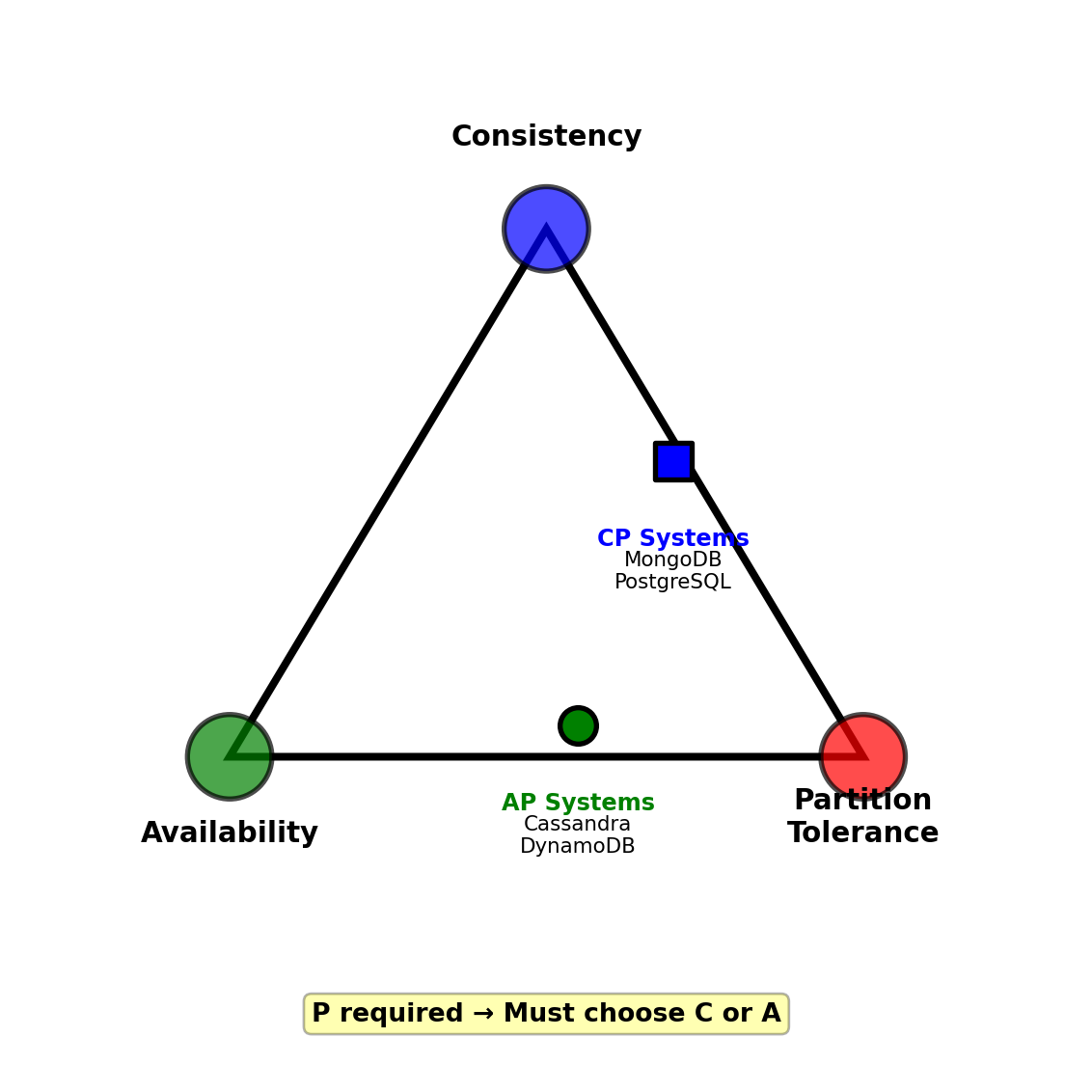

CAP Theorem Forces a Choice During Partitions

Three properties distributed systems want:

Consistency (C):

- All nodes return same value for same query

- Read always returns most recent write

- No stale data

Availability (A):

- Every request gets non-error response

- No timeouts or failures

- System always operational

Partition tolerance (P):

- System works despite network splits

- Required for any distributed system

- Network failures inevitable

CAP Theorem: Cannot have all three during network partition

During partition, must choose:

CP (Consistency + Partition tolerance):

- Reject requests to minority partition

- Guarantees consistency

- Sacrifices availability

AP (Availability + Partition tolerance):

- Accept requests on all partitions

- Guarantees availability

- Sacrifices immediate consistency

Real systems:

- Banking: CP (consistency critical)

- Social media: AP (availability critical)

- Inventory: CP (avoid overselling)

- Analytics: AP (stale data acceptable)

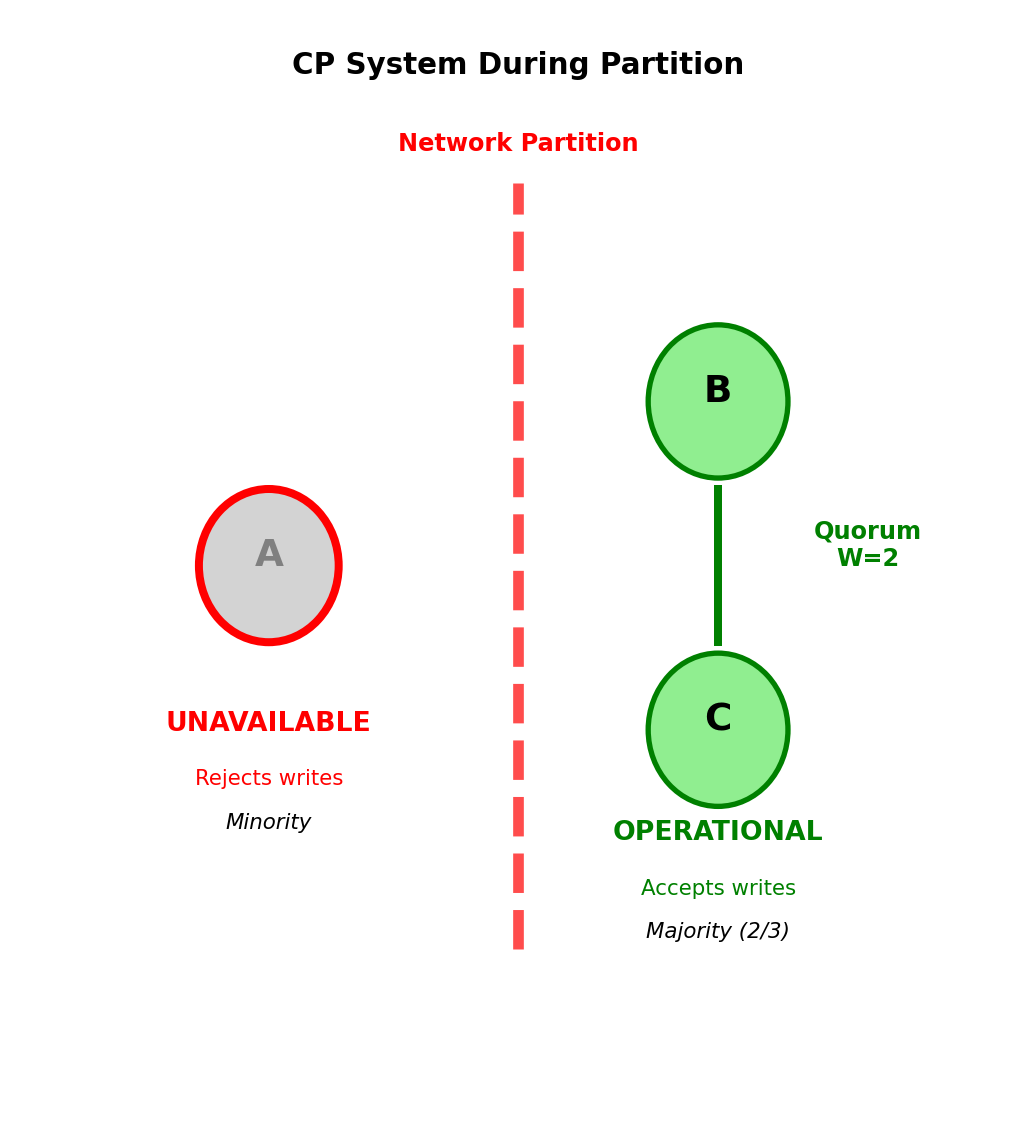

CP Systems Sacrifice Availability for Consistency

CP behavior during partition: [Node A] | [Nodes B, C]

Minority partition (Node A):

- Rejects all write requests: “Error: Cannot reach majority”

- May reject reads (depending on configuration)

- Becomes unavailable to clients

Majority partition (Nodes B, C):

- Continues accepting writes

- Requires majority (2 of 3 nodes) for writes

- Guarantees no conflicting data

After partition heals:

- Node A syncs from B or C

- No conflicts to resolve

- Data guaranteed consistent

Write quorum: W > N/2

- 3 nodes: Must write to 2 nodes

- Latency: Wait for slowest of 2 nodes

- Cost: Higher latency, possible unavailability

PostgreSQL example:

- Primary fails → replica promoted

- Failover time: 30-120 seconds

- During failover: All writes fail

- After: Guaranteed consistency

Use CP when:

- Financial transactions (no double-spending)

- Inventory (no overselling)

- User authentication (no conflicting state)

Trade-off: Latency and availability for guaranteed consistency

AP Systems Sacrifice Consistency for Availability

AP behavior during partition: [Node A] | [Nodes B, C]

Both partitions accept writes:

- Node A: Accepts writes from its clients

- Nodes B, C: Accept writes from their clients

- Result: Divergent data versions

Example conflict:

Node A: user.balance = 100 (withdraw $50)

Node B: user.balance = 120 (deposit $20)

Initial: user.balance = 150

After partition heals: Which is correct?Conflict resolution strategies:

1. Last-write-wins (timestamp):

- Keep write with latest timestamp

- Simple, fast

- Risk: Clock skew causes wrong choice, data loss

2. Application merge:

- Application logic combines conflicts

- Example: Both transactions valid → balance = 70

- Correct but complex

3. Vector clocks:

- Track causality between writes

- Detect concurrent writes

- DynamoDB approach

Cassandra example:

- Write with W=1 (any node): 5ms latency

- Always available during partitions

- Read may return stale data

- Eventual consistency: Replicas converge in milliseconds to seconds

Trade-off: Consistency for availability and low latency

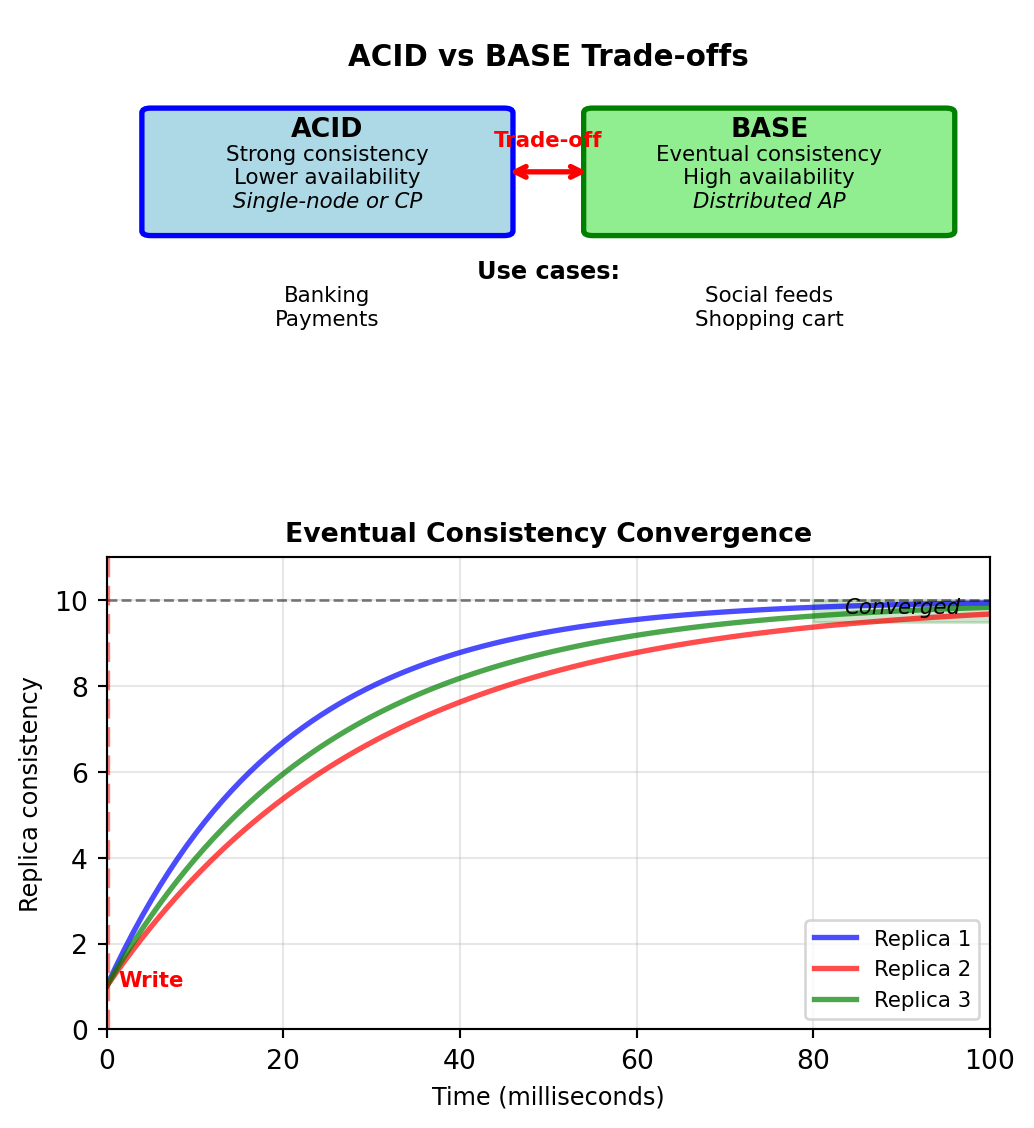

BASE Properties Define AP System Guarantees

ACID (relational databases):

- Atomic: All or nothing

- Consistent: Constraints enforced

- Isolated: Concurrent transactions don’t interfere

- Durable: Committed data survives failures

BASE (distributed systems):

- Basically Available: System responds even during failures

- Soft state: State may change without input (due to eventual consistency)

- Eventual consistency: Replicas converge given enough time

Basically Available:

- System operational during network partitions

- May return stale data or degraded service

- Prioritizes availability over correctness

Soft State:

- No guaranteed consistency at any given moment

- State changes as updates propagate

- Application must handle inconsistencies

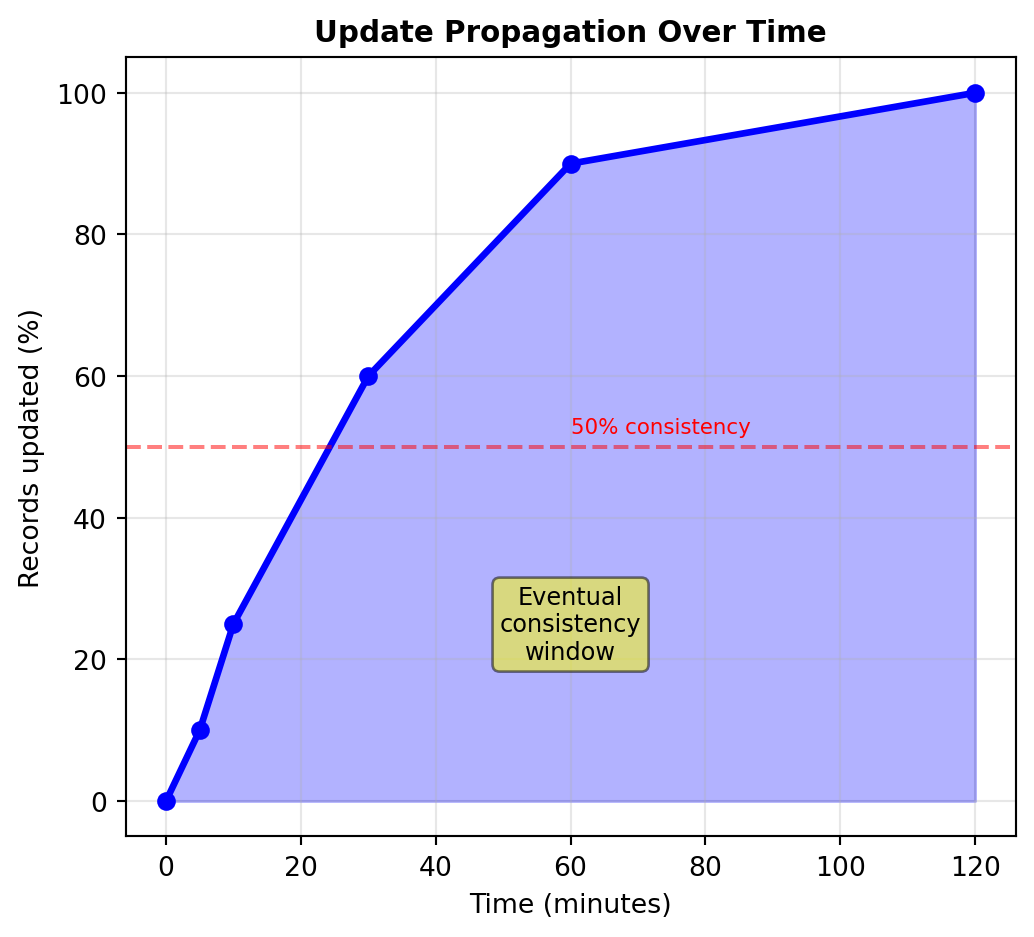

Eventual Consistency:

- All replicas converge to same value

- Time window: milliseconds to seconds

- No guarantee when convergence occurs

Practical implications:

- Read from replica: May get old value

- Write to one node: Other nodes lag behind

- Network partition: Nodes diverge temporarily

- Partition heals: Conflict resolution required

BASE trades immediate consistency for availability and partition tolerance (AP in CAP)

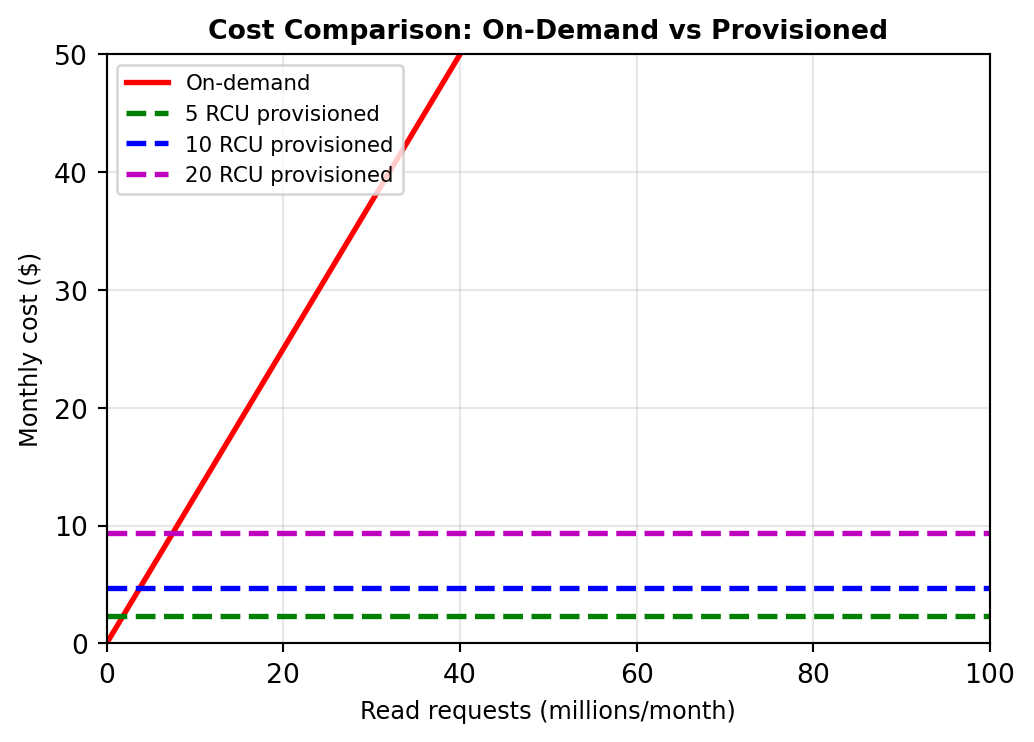

Tunable Consistency Balances Trade-offs

Modern systems allow per-query consistency level

Cassandra consistency levels:

ONE: Return after 1 replica responds

- Latency: 5ms

- Consistency: Eventual (may read stale)

- Availability: High (works with 1 node)

QUORUM: Return after majority responds (R+W > N)

- Latency: 20ms

- Consistency: Strong (if W=QUORUM also)

- Availability: Medium (needs majority alive)

ALL: Return after all replicas respond

- Latency: 50ms

- Consistency: Strong

- Availability: Low (all nodes must be up)

DynamoDB read options:

- Eventually consistent: 5ms, may be stale

- Strongly consistent: 10ms, sees all writes

Application chooses per-query:

Consistency vs latency trade-off:

| Level | Replicas | Latency | Consistency | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONE | 1 | 5ms | Eventual | High |

| QUORUM | 2/3 | 20ms | Strong* | Medium |

| ALL | 3/3 | 50ms | Strong | Low |

*If write also uses QUORUM: R+W > N guarantees overlap

Quorum mathematics:

- N = 3 replicas

- W = 2 (write quorum)

- R = 2 (read quorum)

- R + W = 4 > N = 3

- Guarantees: Read overlaps with write nodes

Latency distribution (Cassandra, same datacenter):

- ONE: p50=5ms, p99=10ms

- QUORUM: p50=20ms, p99=50ms

- ALL: p50=50ms, p99=200ms

Application decides trade-off:

- Social feed: ONE (fast, stale OK)

- Shopping cart: QUORUM (consistent)

- Account balance: ALL (critical accuracy)

Different consistency levels optimize different use cases within same system

Key-Value Stores

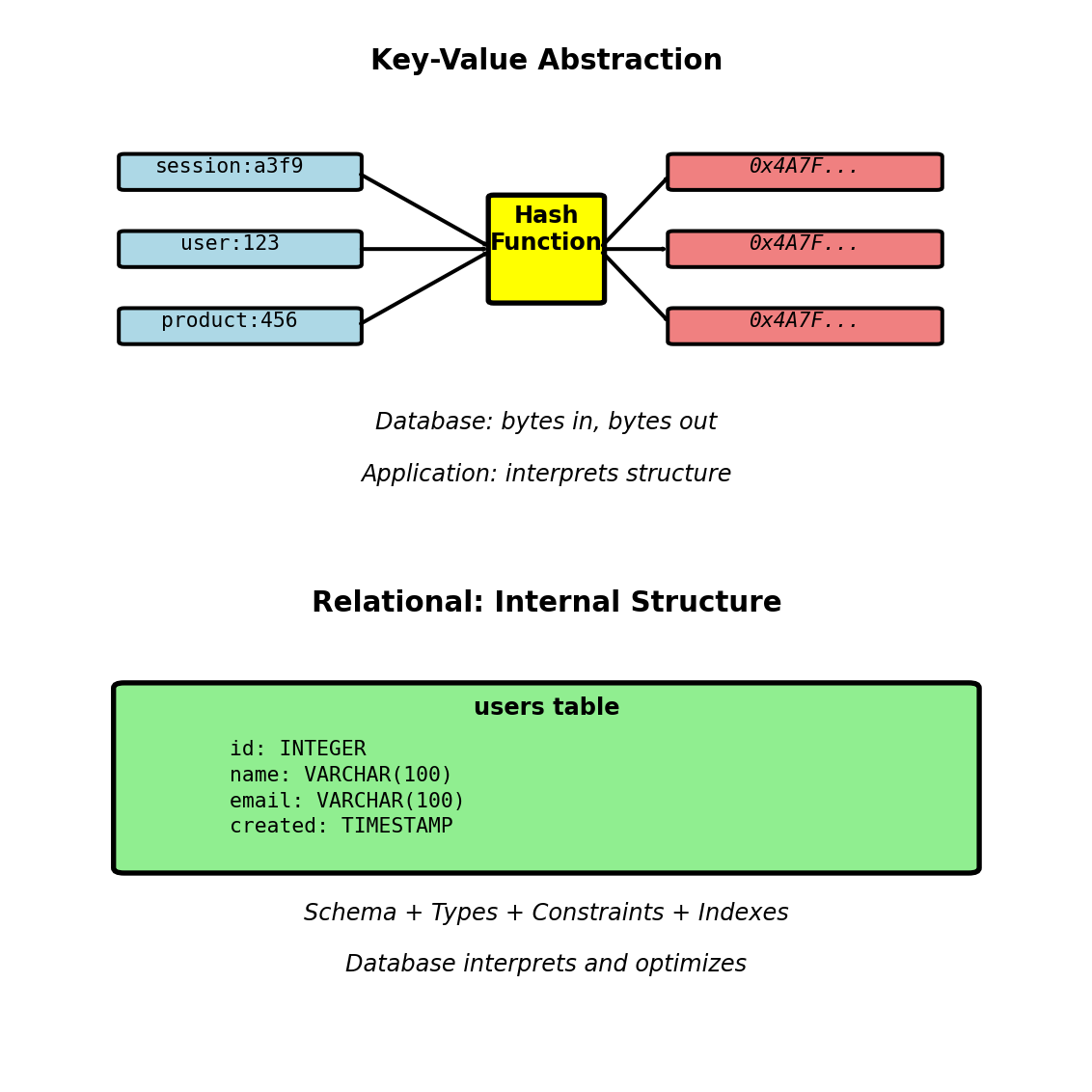

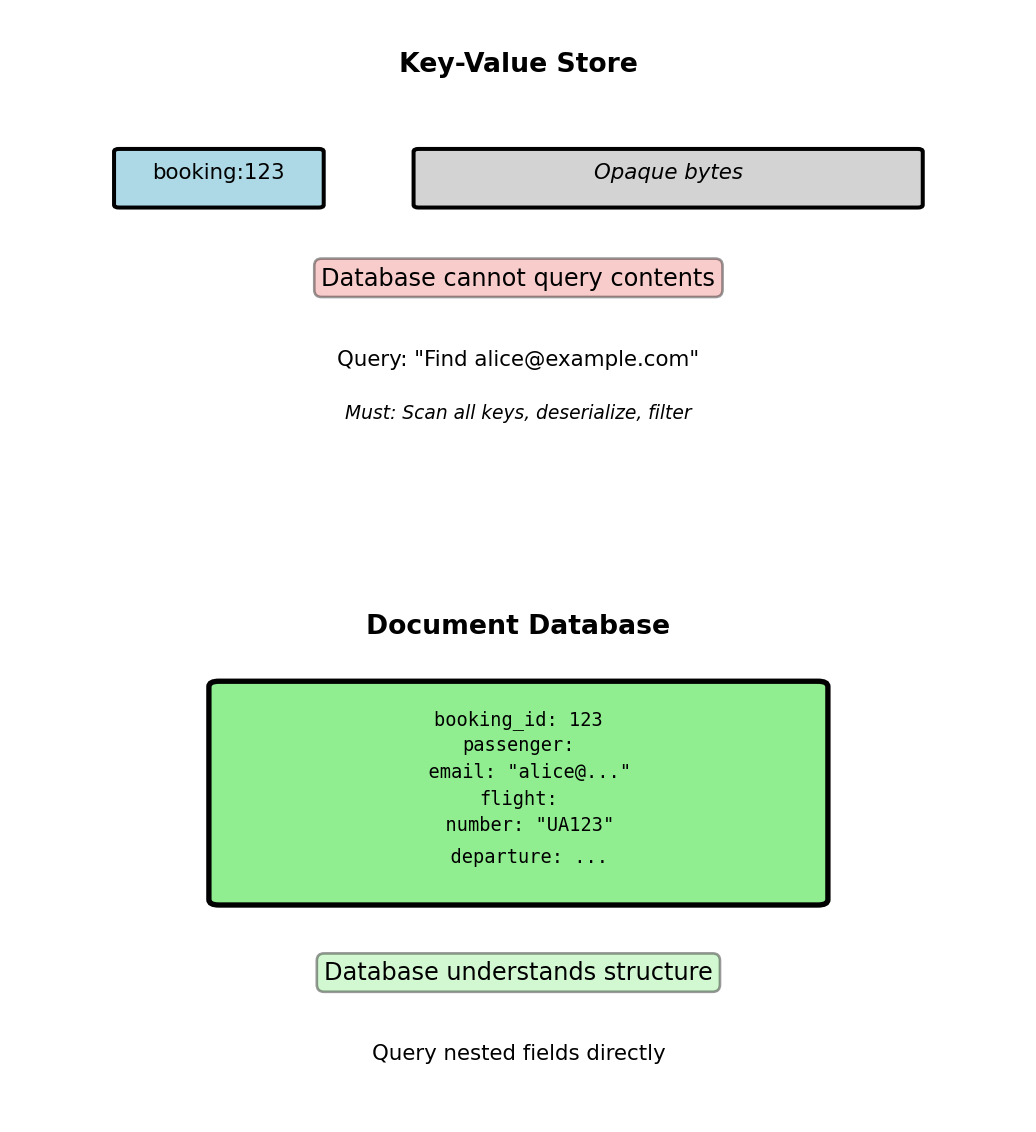

Key-Value Model - Dictionary at Database Scale

Fundamental abstraction:

Value is opaque blob:

- Database does not interpret contents

- No schema enforcement

- No query language for value structure

- Application handles serialization

Examples: Redis, Memcached, Riak, DynamoDB (key-value mode)

Why minimal structure:

- O(1) lookup with hash function

- Trivial horizontal partitioning

- Minimal feature set reduces overhead

- No query parser or optimizer

Contrast with relational:

- Relational: Schema, types, constraints, indexes, query optimizer

- Key-value: Hash table, bytes in/bytes out

- Trade query capability for raw performance

Simple interface provides O(1) access with minimal overhead

Operations Beyond GET/PUT

Core operations:

# Basic

redis.set("key", "value")

redis.get("key")

redis.delete("key")

# Conditional update

redis.setnx("key", "value") # SET if Not eXists

redis.set("key", "new", xx=True) # SET if exists

# Atomic counter

redis.incr("counter") # Atomic increment

redis.decr("counter") # Atomic decrement

# Time to live

redis.setex("session:abc", 1800, data) # 30 min TTL

redis.expire("key", 3600) # Set TTL on existing keyAdvanced (Redis):

Cannot do:

- Query on value contents without retrieving

- Secondary indexes

- Joins across keys

- Aggregations without application logic

Example session showing operations:

#| echo: true

#| eval: false

# Store session with 30-minute expiration

import redis

import json

r = redis.Redis()

session_data = {

"user_id": 123,

"login_time": "2025-01-15T10:30:00Z",

"cart": ["product_456", "product_789"]

}

# Store

r.setex(

"session:a3f9b2c1",

1800, # 30 minutes

json.dumps(session_data)

)

# Retrieve

data = r.get("session:a3f9b2c1")

if data:

session = json.loads(data)

print(f"User {session['user_id']} logged in")

else:

print("Session expired or not found")

# Extend TTL

r.expire("session:a3f9b2c1", 1800)

# After 30 minutes: automatic deletion

# No polling, no cleanup jobs requiredOperations execute in microseconds

Must know exact key for retrieval

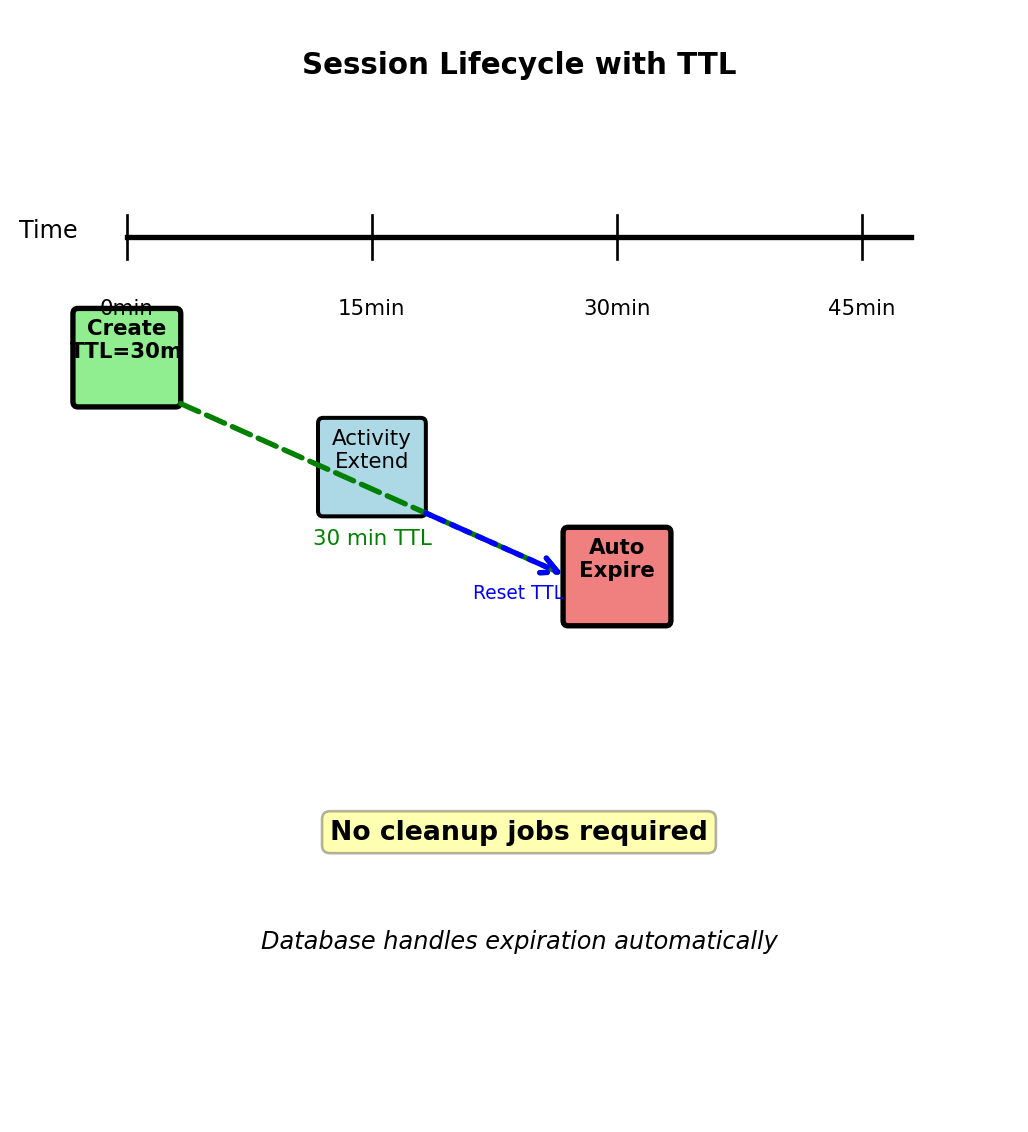

Session Management with Automatic Expiration

Web application session requirements:

- Store per-user state (user_id, preferences, cart)

- Expire after inactivity (30 minutes typical)

- High volume (every HTTP request checks session)

- Fast access (< 5ms latency requirement)

Relational approach problems:

CREATE TABLE sessions (

session_id VARCHAR(64) PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT,

data JSONB,

created_at TIMESTAMP,

last_activity TIMESTAMP

);

-- Every request

SELECT * FROM sessions

WHERE session_id = ?

AND last_activity > NOW() - INTERVAL '30 minutes';

-- Cleanup job (runs every minute)

DELETE FROM sessions

WHERE last_activity < NOW() - INTERVAL '30 minutes';Issues:

- Cleanup job scans millions of rows

- Index on last_activity, but still expensive

- Delete locks table

- Write amplification: Record activity on every request

Key-value with TTL:

Performance:

- Session check: < 1ms (in-memory)

- Relational: 10-50ms (disk, index lookup, expiration check)

- Automatic cleanup vs periodic scan

Value Serialization - Application Choice

Database stores bytes, application chooses format:

JSON - Human readable:

MessagePack - Binary efficient:

Protocol Buffers - Typed schema:

Trade-offs:

JSON:

- Debug with redis-cli

- Language interop trivial

- Larger size

- Slower parse

MessagePack:

- Opaque in redis-cli

- Smaller, faster

- Language support good

- No schema definition

Protocol Buffers:

- Smallest, fastest

- Schema migration paths

- Requires .proto files

- Build step required

Most applications: JSON for simplicity

High-throughput systems: Binary formats

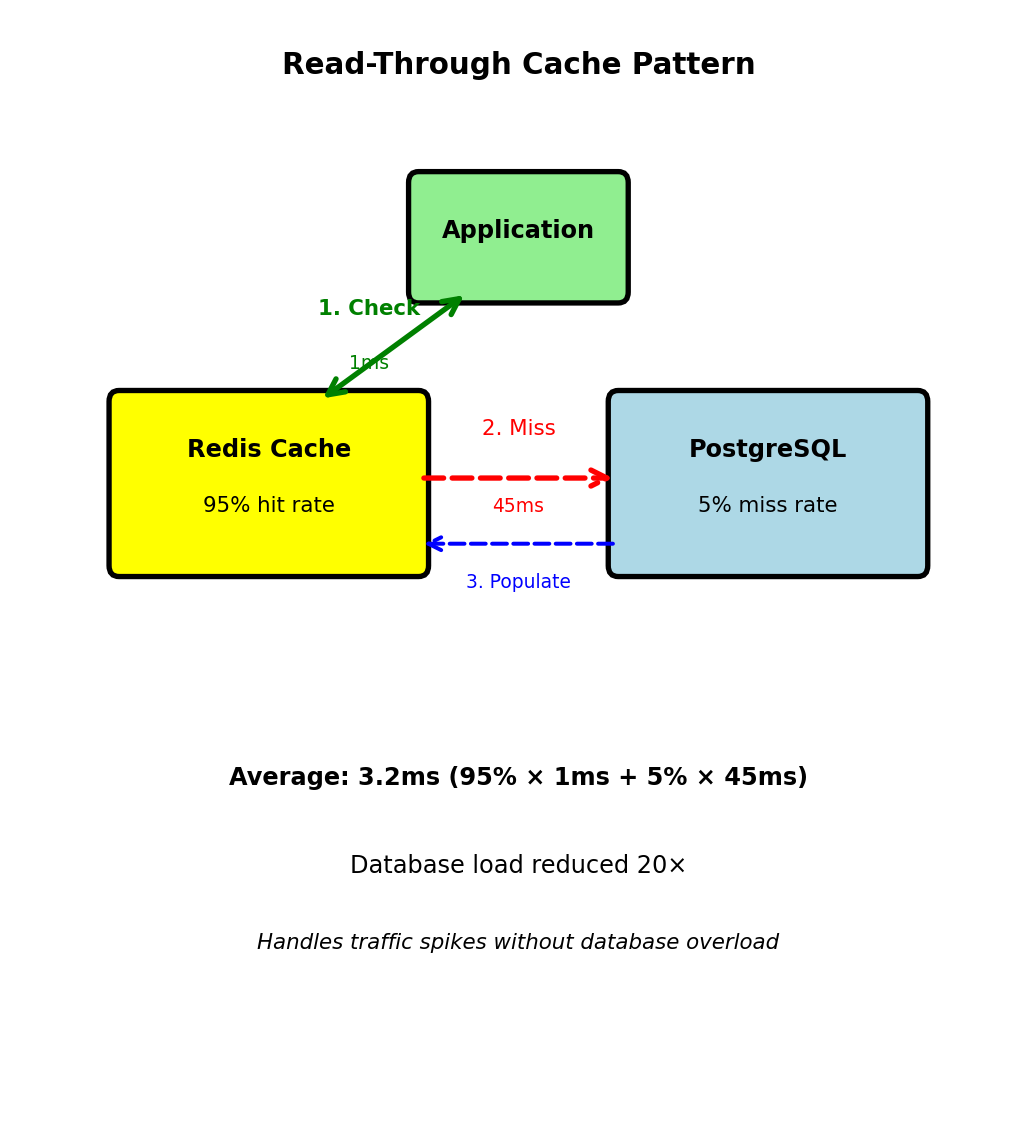

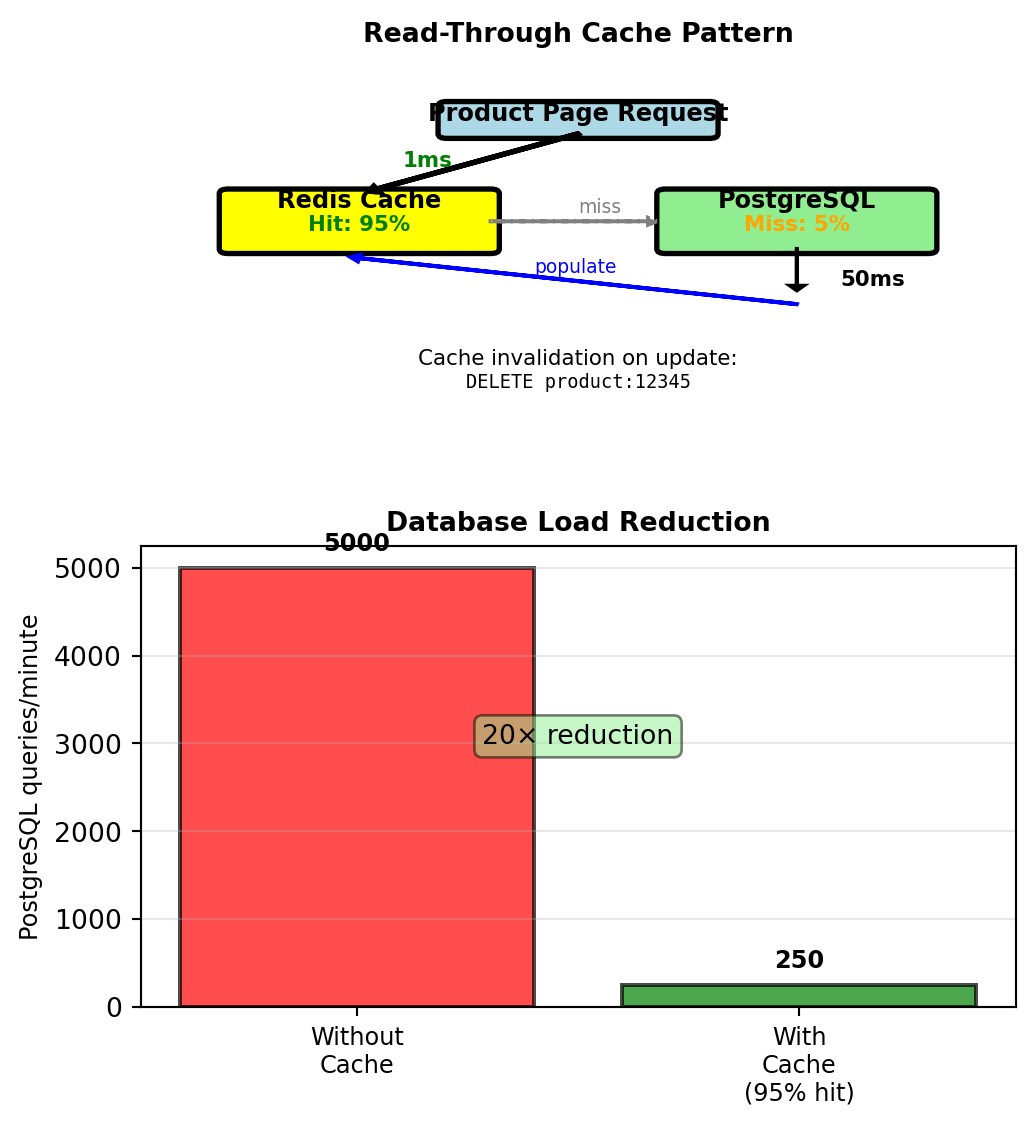

Caching Database Queries - Read-Through Pattern

Product catalog query:

Execution time: 45ms (JOIN, disk I/O)

Cache layer intercepts:

def get_product(product_id):

cache_key = f"product:{product_id}"

# Check cache

cached = redis.get(cache_key)

if cached:

return json.loads(cached) # 1ms

# Cache miss - query database

product = db.execute("""

SELECT p.*, c.name AS category_name

FROM products p

JOIN categories c ON p.category_id = c.category_id

WHERE p.product_id = ?

""", product_id) # 45ms

# Cache result for 5 minutes

redis.setex(cache_key, 300, json.dumps(product))

return productPerformance calculation:

- Cache hit rate: 95%

- Average latency: 0.95 × 1ms + 0.05 × 45ms = 3.2ms

- vs without cache: 45ms

- 14× faster average response

Database load reduction:

- 1000 requests/second

- Without cache: 1000 database queries/second

- With 95% hit rate: 50 database queries/second

- 20× reduction in database load

Cache absorbs read load

Database handles writes and cache misses

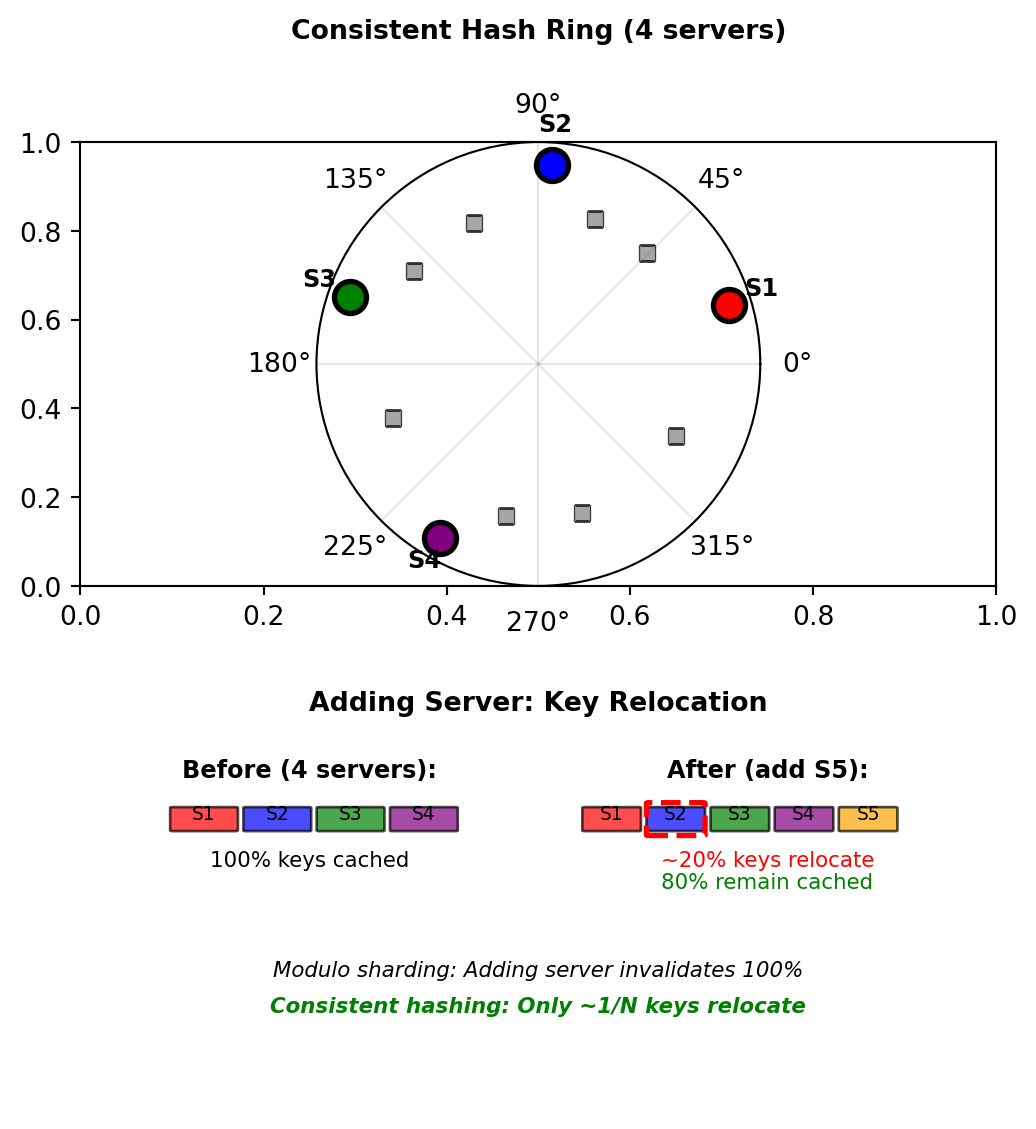

Distributed Caching with Consistent Hashing

Single cache server limit:

- 64GB RAM = ~50M cached items

- Network bandwidth: 10Gbps

- Need horizontal scaling

Naive sharding breaks:

Adding server changes N → all keys remap

Consistent hashing solution:

- Hash ring: 0 to 2³²-1

- Servers and keys both hash to ring positions

- Key stored on next clockwise server

- Adding server: Only adjacent keys relocate (~1/N)

Example with 4 servers:

# Server positions on ring (hash of server ID)

servers = {

"server1": hash("server1") % (2**32), # 428312345

"server2": hash("server2") % (2**32), # 1827364829

"server3": hash("server3") % (2**32), # 2913746582

"server4": hash("server4") % (2**32), # 3728191028

}

# Key placement

key_hash = hash("product:456") % (2**32) # 945628371

# Finds next server clockwise: server2Adding server5:

- New position: 2100000000

- Only keys between server2 and server5 relocate

- ~25% of keys move (1/4 servers)

- Other 75% remain cached

Hash slots distribute cache load without global invalidation

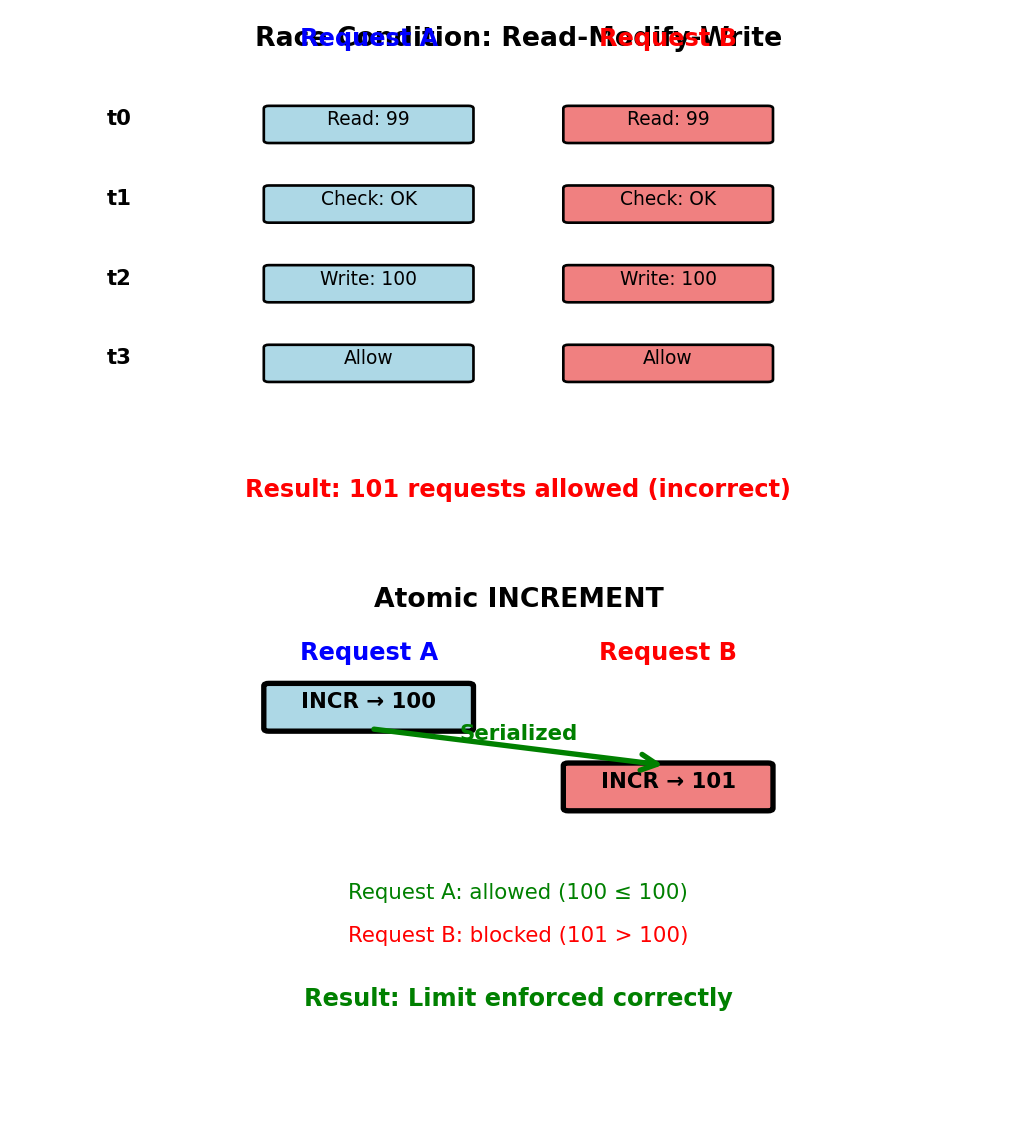

Rate Limiting with Atomic Counters

API rate limit: 100 requests per minute per user

Wrong approach - Race condition:

Problem with concurrent requests:

Time Request A Request B

t0 Read count=99 Read count=99

t1 Check: 99 < 100 Check: 99 < 100

t2 Set count=100 Set count=100

t3 Allow request Allow requestBoth requests see count=99, both allowed → 101 requests

Correct approach - Atomic operation:

Atomic increment guarantees correct count under concurrency

Single round-trip, no race conditions

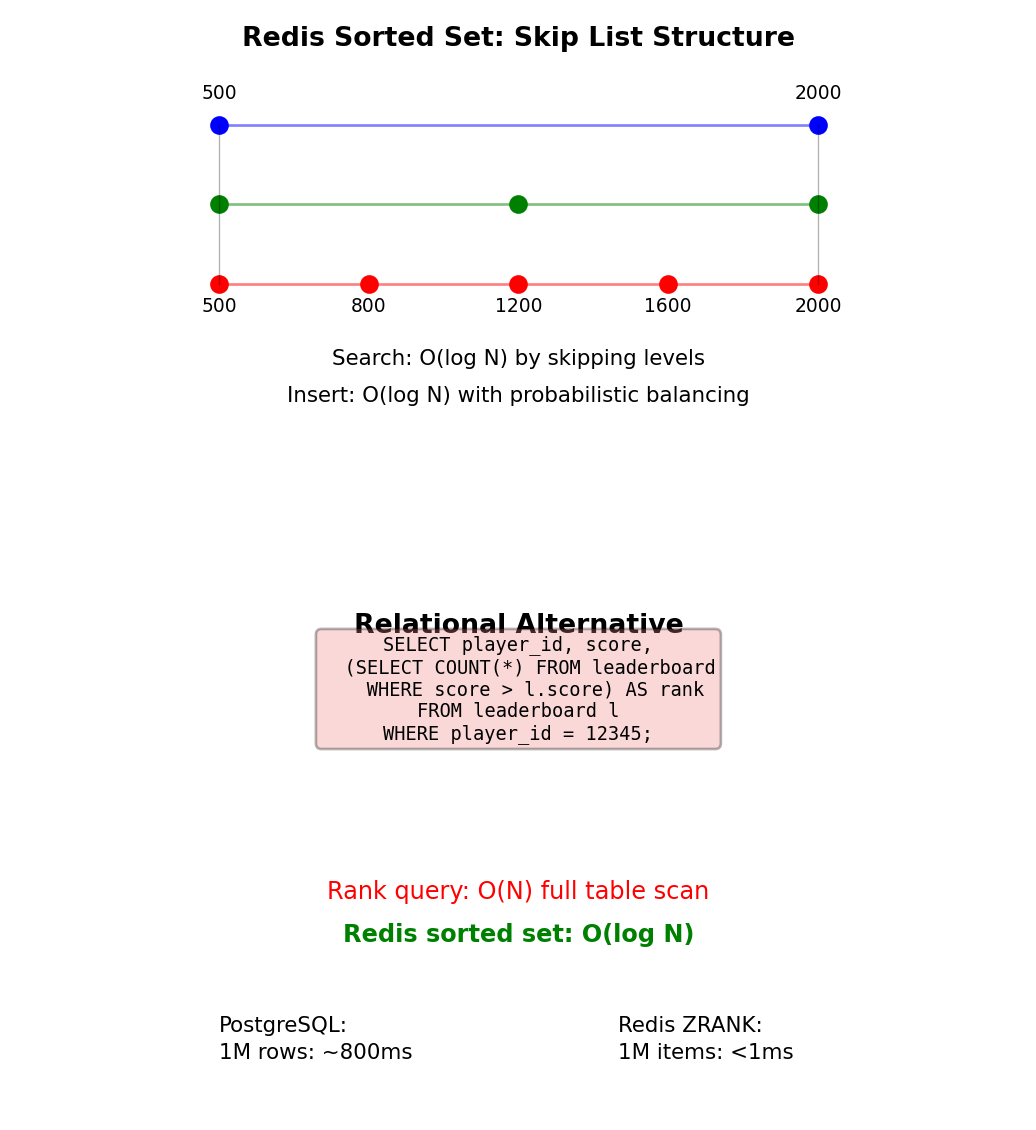

Leaderboards with Sorted Sets

Gaming leaderboard requirements:

Rank 1 million players by score

Update scores frequently (every game completion)

Query operations:

- Player rank: “What rank is player_id=12345?”

- Top N: “Who are top 10 players?”

- Score range: “Players with 1000-2000 points”

Redis sorted set:

import redis

r = redis.Redis()

# Update player score (O(log N))

r.zadd("leaderboard", {"player_12345": 1850})

r.zadd("leaderboard", {"player_67890": 2100})

# Get player rank - 0-indexed, from lowest (O(log N))

rank = r.zrevrank("leaderboard", "player_12345")

# Returns: 43127 (meaning 43,128th place)

# Get top 10 players with scores (O(log N + 10))

top_10 = r.zrevrange("leaderboard", 0, 9, withscores=True)

# Returns: [("player_67890", 2100.0), ...]

# Get players in score range (O(log N + M))

players = r.zrangebyscore("leaderboard", 1000, 2000)

# Get player score (O(1))

score = r.zscore("leaderboard", "player_12345")All operations logarithmic or better with 1M players

Internal structure: Skip list

Specialized data structure for ranking operations

Key-Value Limitations

Cannot query on value contents:

All sessions for user:

# Need to track session keys separately

redis.sadd(f"user_sessions:{user_id}", session_id)

# Or scan all keys (expensive)

cursor = 0

sessions = []

while True:

cursor, keys = redis.scan(cursor, match="session:*")

for key in keys:

data = json.loads(redis.get(key))

if data["user_id"] == target_user:

sessions.append(data)

if cursor == 0:

break

# Scans entire keyspace, O(N) operationProducts under $20:

Application must manually maintain indexes

No relationships:

No JOIN operation

No multi-key transactions (usually):

Redis transactions limited:

# WATCH/MULTI/EXEC for optimistic locking

redis.watch("account:A", "account:B")

balance_a = redis.get("account:A")

balance_b = redis.get("account:B")

pipe = redis.pipeline()

pipe.set("account:A", balance_a - 100)

pipe.set("account:B", balance_b + 100)

result = pipe.execute() # Fails if watched keys modifiedDynamoDB: 25 item transaction limit

When key-value is wrong:

- Complex queries on attributes

- Relationships between entities

- Consistency across multiple items

- Need secondary indexes on value fields

When key-value is right:

- Known exact key for access

- Simple GET/PUT operations dominate

- High throughput, low latency required

- Data can be denormalized per key

- Temporary or cached data

Key-value complements relational, does not replace

Document Databases

Document Model - Structured Objects as Storage Unit

Document database stores structured objects as atomic units

Recall embed vs reference patterns from earlier. Document databases implement these patterns while understanding document structure.

Key-value limitation:

Document database capability:

Database parses JSON structure to support:

- Queries on nested fields without deserialization

- Indexes on any field, including nested

- Aggregations across document contents

- Structure validation

Primary implementations: MongoDB (BSON), CouchDB (JSON), DocumentDB

Document databases bridge gap between key-value flexibility and relational query power

MongoDB Collections and Documents

Collection: Group of related documents (analogous to relational table)

Document: Single JSON object with _id primary key

No enforced schema: Documents in same collection can have different fields

Booking collection example:

MongoDB-specific types:

ObjectId: 12-byte unique identifier (timestamp + random)ISODate: Native datetime type (UTC)NumberLong,NumberDecimal: Typed numeric values- Embedded documents and arrays

Storage format: BSON (Binary JSON)

- Binary encoding: More efficient than text JSON

- Additional types: Date, Binary, Decimal128, ObjectId

- Preserves field order (unlike JSON spec)

- ~1.5× space overhead vs raw JSON for typical documents

Collection contains documents with varying fields

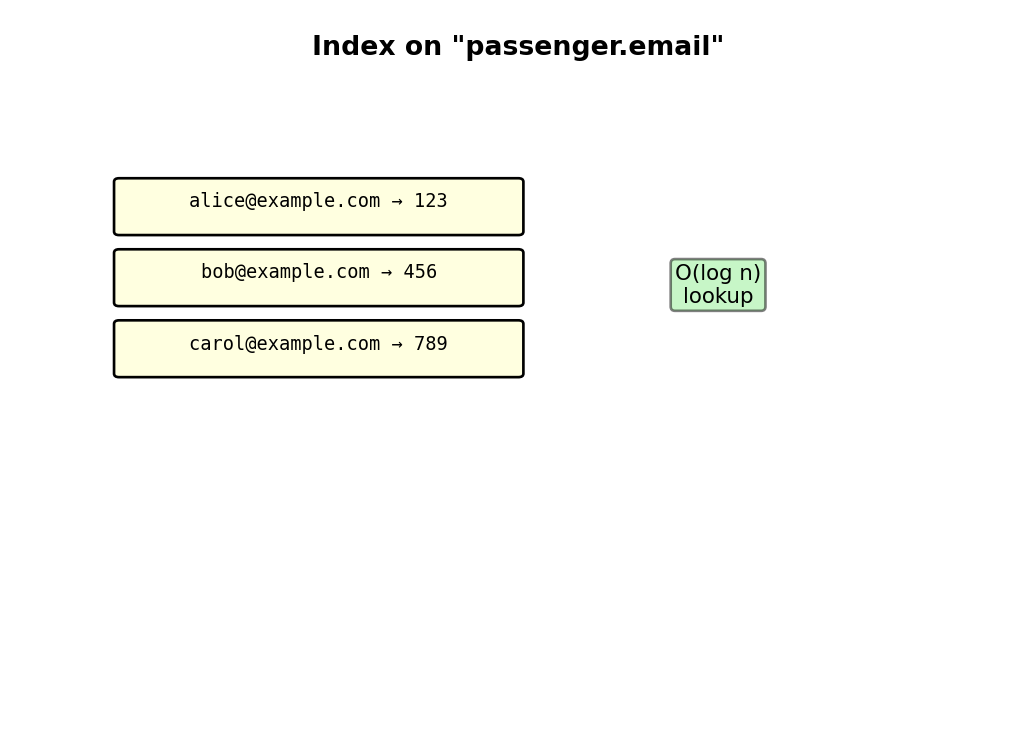

Querying Nested Fields - Dot Notation

Relational limitation: Accessing nested data required JOINs

Document structure with nesting:

Dot notation queries:

// Find bookings for specific email

db.bookings.find({

"passenger.email": "alice@example.com"

})

// Query nested 3 levels deep

db.bookings.find({

"passenger.frequent_flyer.tier": "Gold"

})

// Combine nested and top-level filters

db.bookings.find({

"flight.departure_airport": "LAX",

"flight.scheduled_departure": {

$gte: ISODate("2025-02-01"),

$lt: ISODate("2025-03-01")

}

})Index on nested field:

Query execution with index:

- Nested field indexed like top-level field

- B-tree lookup: O(log n)

- 1M documents: ~2ms query time

Comparison to relational approach:

Performance measurement (1M bookings):

- Document nested query: 2ms

- Relational 2-JOIN query: 15ms

- Difference: JOIN operation cost (hash join on 1M rows)

Why faster:

- Document: Single index lookup + fetch

- Relational: Index lookup + JOIN build + JOIN probe

Nested data stored contiguously eliminates JOIN cost

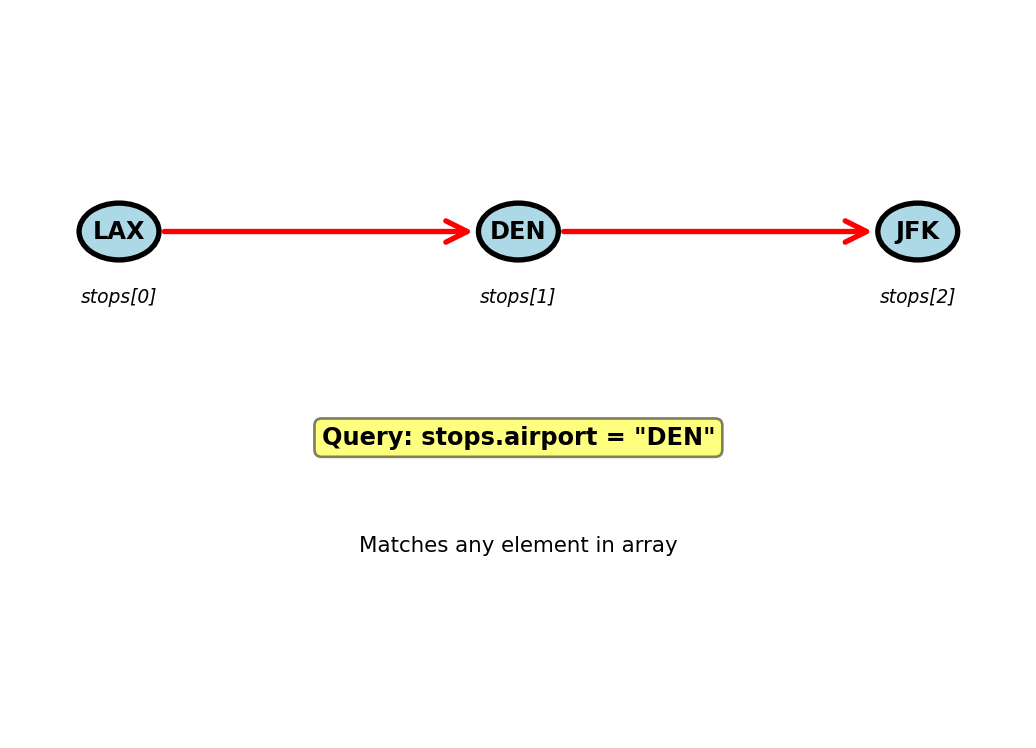

Querying Arrays - Flight Stops Example

Scenario: Multi-stop flights (LAX → DEN → JFK)

{

"flight_id": 789,

"flight_number": "UA456",

"stops": [

{

"airport": "LAX",

"arrival": null,

"departure": ISODate("2025-02-15T08:00:00Z"),

"gate": "B12"

},

{

"airport": "DEN",

"arrival": ISODate("2025-02-15T10:30:00Z"),

"departure": ISODate("2025-02-15T11:00:00Z"),

"gate": "A5"

},

{

"airport": "JFK",

"arrival": ISODate("2025-02-15T17:00:00Z"),

"departure": null,

"gate": "C8"

}

]

}Query any array element:

Query specific array position:

Match array element with multiple conditions:

Array operators:

$elemMatch: Element meets multiple conditions$all: Array contains all specified elements$size: Array has specific length$: Positional operator for updates

Array queries operate across all elements

Indexes on Nested Fields and Arrays

Creating indexes on document structure:

Multikey indexes on arrays:

Query execution:

Index size impact:

- Nested field indexes: Same cost as top-level

- Multikey (array) indexes: Size = sum of array lengths across collection

- 10K flights × 3 stops average = 30K index entries

MongoDB limit: 64 indexes per collection

Indexes work on any document field

Performance (1M documents): Indexed query: 2ms, Collection scan: 500ms

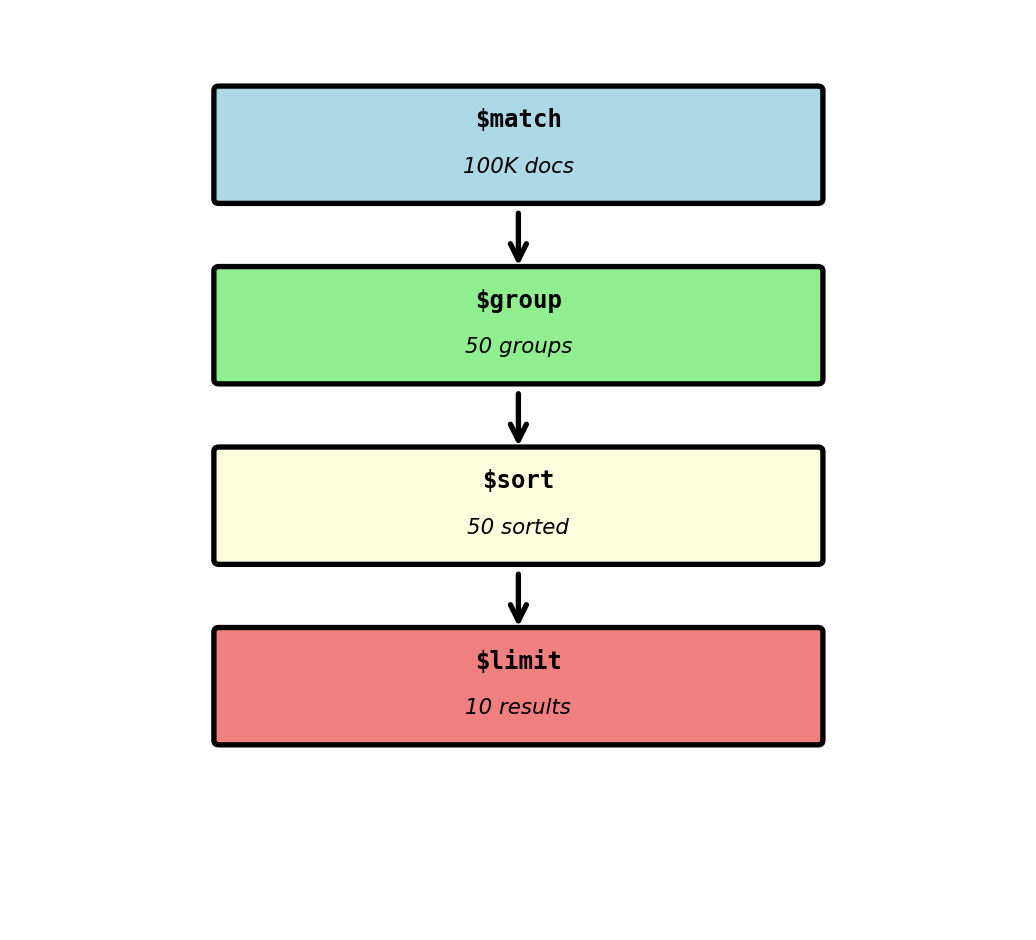

Aggregation Pipeline - Multi-Stage Processing

Query: “Average booking price by departure airport for last 30 days”

Relational approach requires JOIN:

MongoDB aggregation pipeline:

db.bookings.aggregate([

// Stage 1: Filter to last 30 days

{

$match: {

booking_time: {

$gte: ISODate("2025-01-15"),

$lt: ISODate("2025-02-15")

}

}

},

// Stage 2: Group by departure airport

{

$group: {

_id: "$flight.departure_airport",

avg_price: {$avg: "$price"},

total_bookings: {$sum: 1},

min_price: {$min: "$price"},

max_price: {$max: "$price"}

}

},

// Stage 3: Sort by average price descending

{

$sort: {avg_price: -1}

},

// Stage 4: Limit to top 10

{

$limit: 10

}

])Aggregation - Unwind for Array Processing

Problem: Analyze which airports have most stops (connection hubs)

Document with stops array:

Pipeline with $unwind:

db.flights.aggregate([

// Stage 1: Expand stops array

{

$unwind: "$stops"

},

// After $unwind, creates 3 documents:

// {flight_number: "UA456", stops: "LAX"}

// {flight_number: "UA456", stops: "DEN"}

// {flight_number: "UA456", stops: "JFK"}

// Stage 2: Group by airport

{

$group: {

_id: "$stops",

flight_count: {$sum: 1}

}

},

// Stage 3: Sort by frequency

{

$sort: {flight_count: -1}

},

// Stage 4: Top 10 airports

{

$limit: 10

}

])Result:

$unwind document explosion:

Array expansion multiplies document count:

- Input: 10K flight documents

- Average 3 stops per flight

- After $unwind: 30K documents in pipeline

- Memory: 30K × 1KB = 30MB buffered

Optimization: filter before unwind

Pipeline size:

- Filter reduces 10K → 2K flights

- Unwind creates 2K × 3 = 6K documents

- 5× memory reduction vs unwind-first

Measured performance:

- Unwind-first: 850ms, 30MB peak memory

- Filter-first: 180ms, 6MB peak memory

$unwind before $match creates unnecessary work

Schema Validation - Optional Enforcement

Problem: No schema enforcement - errors undetected

- Typo:

emialinstead ofemail - Wrong type:

"123"instead of123 - Missing required field

MongoDB JSON Schema validation:

db.createCollection("bookings", {

validator: {

$jsonSchema: {

bsonType: "object",

required: ["booking_reference", "passenger_id",

"flight_id", "price"],

properties: {

booking_reference: {

bsonType: "string",

pattern: "^[A-Z]{3}[0-9]{3}$",

description: "Format: ABC123"

},

passenger_id: {

bsonType: "int",

minimum: 1

},

price: {

bsonType: "decimal",

minimum: 0,

maximum: 10000

},

passenger: {

bsonType: "object",

properties: {

email: {

bsonType: "string",

pattern: "^.+@.+\\..+$"

}

}

}

}

}

},

validationAction: "error" // or "warn"

})Validation behavior:

Valid insert succeeds:

Invalid insert rejected:

Validation options:

validationAction: "error"- Reject invalid documentsvalidationAction: "warn"- Log warning, allow insertvalidationLevel: "moderate"- Validate only new/updated documents

Trade-off:

- Validation = Type safety, data quality

- No validation = Maximum flexibility, faster writes

- Can enable per-collection based on requirements

Validation provides safety without rigid schema

Update Operations - Document Granularity

Updating nested fields:

Updating array elements:

// Update element by position

db.flights.updateOne(

{flight_id: 789},

{$set: {"stops.1.departure": ISODate("2025-02-15T11:30:00Z")}}

)

// stops[1].departure updated

// Update element by condition ($ positional operator)

db.flights.updateOne(

{flight_id: 789, "stops.airport": "DEN"},

{$set: {"stops.$.departure": ISODate("2025-02-15T11:30:00Z")}}

)

// Updates first matching elementUpdate operators:

Atomicity guarantees:

Single document updates are atomic:

Cross-document operations not atomic (without transactions):

MongoDB 4.0+: Multi-document transactions

Performance: Transactions add overhead (~2-3× slower)

Single-document atomicity sufficient for most embedded designs

Document Size Limits and Denormalization Trade-offs

MongoDB document constraints:

- Maximum document size: 16MB

- Maximum nesting depth: 100 levels

- No hard limit on array length (constrained by 16MB total)

When embedding breaks:

Flight with all bookings embedded:

Problems at scale:

- Works for 200 bookings (200KB < 16MB)

- Each booking addition rewrites entire 200KB document

- Concurrent booking updates conflict (document-level locking)

- 180-seat plane sold out: 180 document rewrites

- Reading flight details loads unnecessary 200KB

When to reference instead of embed:

- Unbounded growth (user’s order history over years)

- Independent access patterns (query bookings without flight)

- High update frequency (seat assignments change constantly)

- Size exceeds reasonable threshold (>100KB per document)

Reference pattern (normalized approach):

// Flight document (small, stable)

{

"flight_id": 456,

"flight_number": "UA123",

"departure_airport": "LAX",

"arrival_airport": "JFK",

"scheduled_departure": ISODate("2025-02-15T14:30:00Z"),

"seats_available": 12,

"total_seats": 180

}

// Size: 1KB

// Booking documents (separate collection)

{

"booking_id": 789,

"flight_id": 456, // Reference

"passenger_id": 123,

"seat": "12A"

}

// 180 separate documentsQuery patterns:

Reference when size or update patterns break embedding

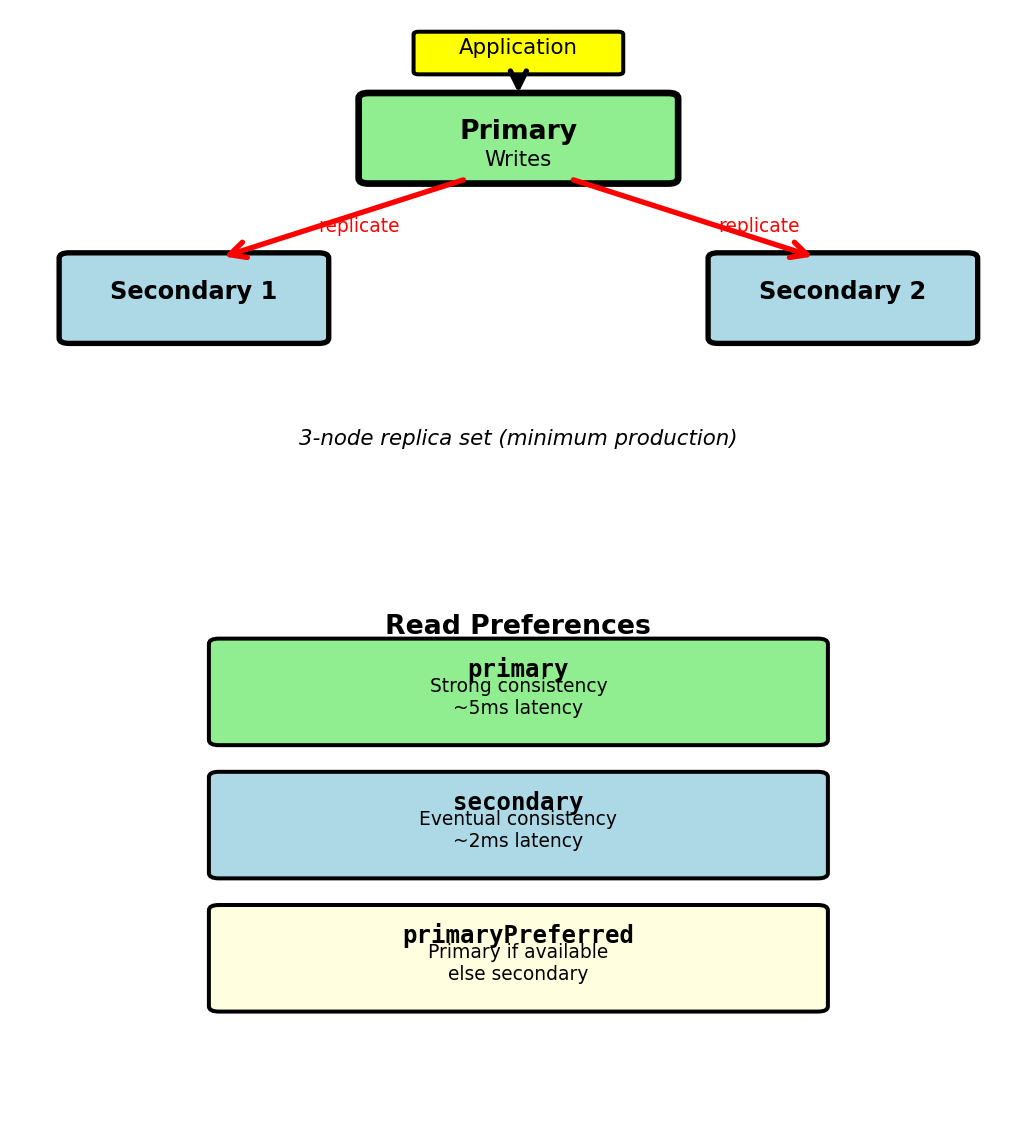

MongoDB in Production - Replica Sets

Single server limitations:

- Hardware failure → data loss

- Maintenance → downtime

- No geographic distribution

- Read throughput limited to single machine

Replica set architecture:

- Primary node: Handles all writes

- Secondary nodes (2+): Replicate from primary

- Automatic failover: Secondary elected if primary fails

- Production minimum: 3 nodes (1 primary + 2 secondaries)

Write path:

Write concern controls durability:

Replication lag:

- Typical: < 100ms (local network)

- Under heavy write load: Can reach seconds

- Network partition: Unbounded until resolved

Document Database Limitations - Cross-Collection Queries

Problem: Analytics across referenced data

Using normalized reference pattern:

Query: “Total revenue by departure airport”

Relational approach:

**MongoDB \(lookup (LEFT JOIN):** ```javascript db.flights.aggregate([ {\)lookup: { from: “bookings”, localField: “flight_id”, foreignField: “flight_id”, as: “bookings” }}, {\(unwind: "\)bookings”}, {\(group: { _id: "\)departure_airport”, total_revenue: {\(sum: "\)bookings.price”} }} ]) // Executes in ~450ms vs ~50ms embedded

:::

::: {.column width="45%"}

**Performance difference:**

**$lookup implementation:**

- Nested loop join (no hash join optimization)

- For each flight, scan bookings collection

- 10K flights × 100K bookings = 1B comparisons

- No query optimizer reordering

**Workaround: Denormalize**

```javascript

// Store departure_airport in booking

{

booking_id: 789,

flight_id: 456,

departure_airport: "LAX", // Duplicated

price: 450

}

// Now simple aggregation

db.bookings.aggregate([

{$group: {

_id: "$departure_airport",

total_revenue: {$sum: "$price"}

}}

])

// Executes in ~25msCost of denormalization:

- Airport code duplicated in 500K bookings

- Flight route change: Update 500K documents

- Acceptable if routes rarely change

Reference patterns sacrifice cross-collection query performance

Document Database Limitations - Consistency Guarantees

Problem: Seat inventory management

Relational ACID transaction:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

-- Check seat available

SELECT available_seats FROM flights

WHERE flight_id = 456 FOR UPDATE;

-- available_seats = 1

-- Book seat

INSERT INTO bookings (flight_id, passenger_id, seat)

VALUES (456, 123, '12A');

-- Decrement inventory

UPDATE flights SET available_seats = available_seats - 1

WHERE flight_id = 456;

COMMIT;Two concurrent transactions:

- Transaction A checks: 1 seat available

- Transaction B checks: 1 seat available

- Both proceed? No -

FOR UPDATElock prevents race

MongoDB without transactions:

Race condition: Both bookings succeed, seats go negative

Solution: Atomic update with condition

result = db.flights.updateOne(

{flight_id: 456, available_seats: {$gt: 0}},

{

$inc: {available_seats: -1},

$push: {recent_bookings: booking_id}

}

)

if (result.modifiedCount === 1) {

// Success - seat was available and decremented

db.bookings.insertOne({...})

} else {

// Failed - no seats available

}Works for single-document atomicity, but:

- Booking still inserted after seat check

- If second insert fails, seat already decremented

- Inconsistent state possible

Multi-document transactions (MongoDB 4.0+):

Performance cost:

- Transactions 2-3× slower than single operations

- Requires replica set coordination

- Contention on hot documents

Document model assumes independent documents - cross-document consistency expensive

Wide-Column Stores

Wide-Column Model - Tables Without Fixed Schema

Sparse data problem:

- Flight events: delay, diversion, emergency

- Relational: Fixed columns, mostly NULL

- 1M flights × 20 event columns = 19M NULL values (95%)

Wide-column approach:

- Rows can have different columns

- Store only non-NULL values

- Columns grouped into column families

- Physical storage: Column-oriented, not row-oriented

Examples: Apache Cassandra, HBase, Google Bigtable

Flight 12345 (delay event):

row_key: "flight_12345"

standard: flight_number="UA123", departure="LAX", arrival="JFK"

events: delay_reason="weather", delay_minutes=45Flight 12346 (emergency event):

row_key: "flight_12346"

standard: flight_number="AA456", departure="JFK", arrival="SFO"

events: emergency_type="medical", diverted_airport="DEN"Different columns per row, no NULL storage

Storage: 75% reduction by eliminating NULL columns

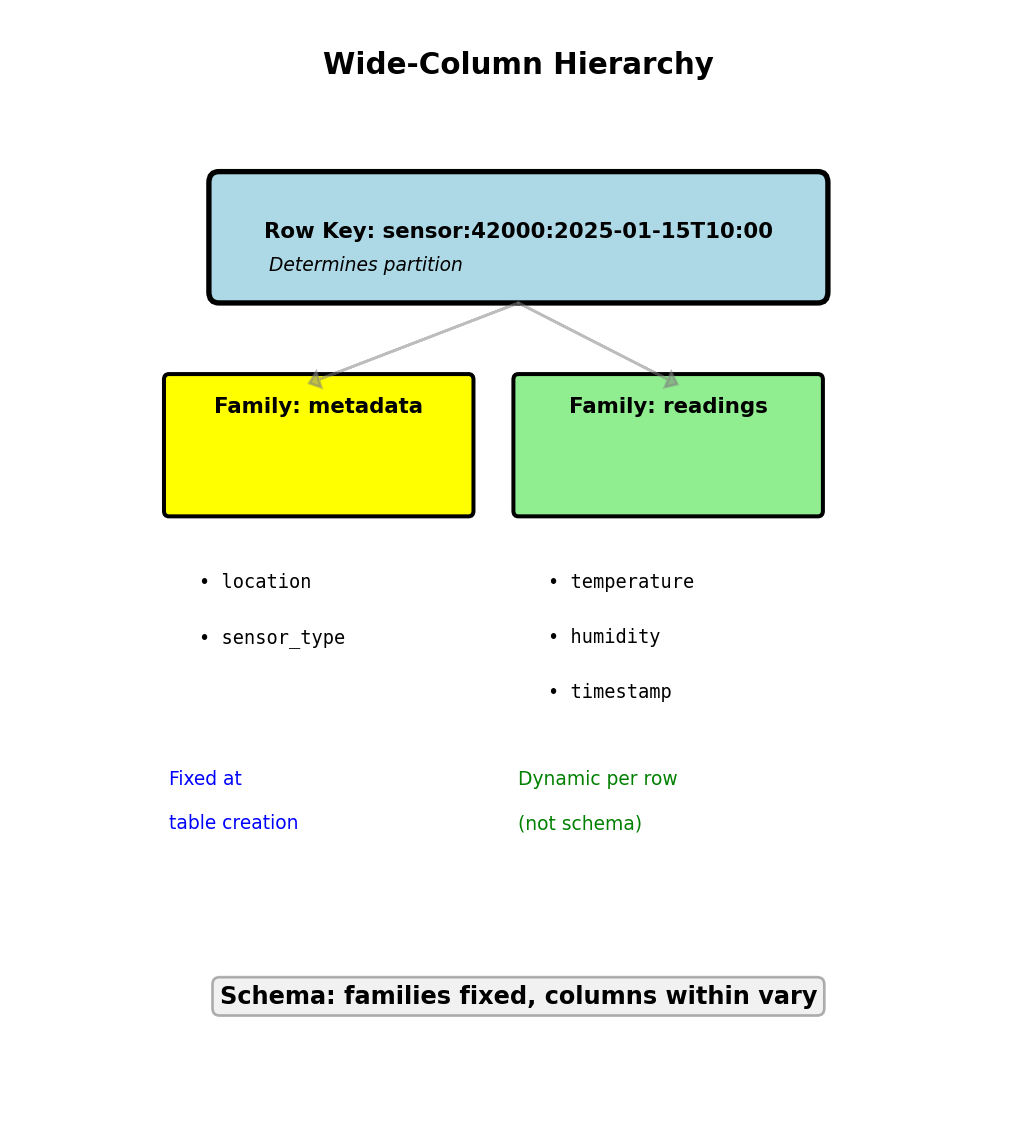

Data Model - Row Key, Column Families, Columns

Three-level hierarchy:

1. Row key:

- Unique identifier

- Determines partition (which nodes store data)

- Sorted lexicographically

- Example:

sensor:42000:2025-01-15

2. Column family:

- Logical grouping of related columns

- Defined at table creation

- Physical storage unit: columns in family stored together

- Examples:

metadata,readings,events

3. Column:

- Key-value pair within family

- Column name is part of the data (not schema)

- Each row can have different columns

- Example:

readings:temperature=22.5

Physical storage example:

row_key="sensor:42000:2025-01-15T10:00"

metadata:location = "Building A, Floor 3"

metadata:sensor_type = "indoor_temp"

readings:temperature = 22.5

readings:humidity = 45.0

readings:timestamp = "2025-01-15T10:00:00Z"Different sensor might have:

row_key="sensor:42001:2025-01-15T10:00"

metadata:location = "Building B, Floor 1"

metadata:sensor_type = "motion"

readings:x_accel = 0.05

readings:y_accel = 0.12

readings:z_accel = 9.81

Column families provide structure, columns provide flexibility

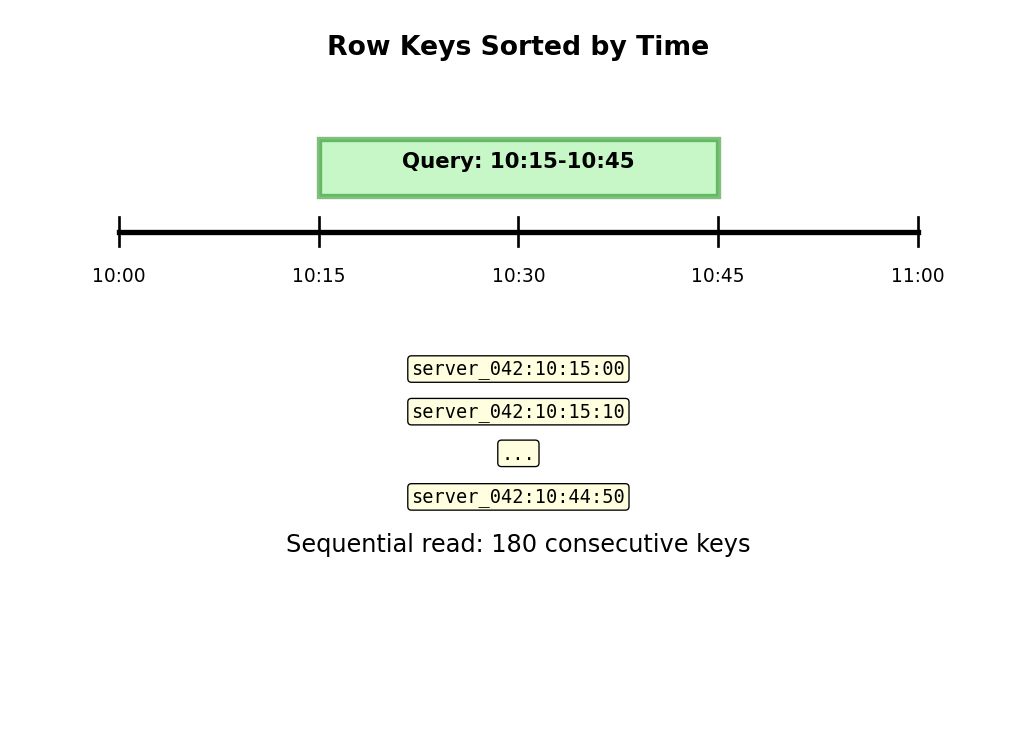

Time-Series Data - Natural Fit for Wide-Column

Scenario: Server monitoring metrics

- 10,000 servers

- Metrics every 10 seconds: CPU, memory, disk I/O, network

- Sparse: I/O metrics only when disk active (~30% of time)

- Retention: 90 days

Data volume:

- 10,000 servers × 6 samples/minute = 60,000 writes/minute

- 86.4M samples/day

- 90 days = 7.78B samples

Row key design: server_id:timestamp

server_042:2025-01-15T10:30:00

server_042:2025-01-15T10:30:10

server_042:2025-01-15T10:30:20Lexicographic sort → time-adjacent data stored adjacently

Query: “Server 42, last hour”

Start: server_042:2025-01-15T09:30:00

End: server_042:2025-01-15T10:30:00Sequential read of 360 consecutive row keys

Column families:

system: cpu_percent=45.2, memory_mb=8192, uptime_sec=345600

disk: read_iops=120, write_iops=80, queue_depth=3

(only when disk active)

network: rx_bytes=1048576, tx_bytes=524288, connections=42

Time-ordered row keys enable efficient range queries

Storage efficiency (1M samples): Relational with NULLs: 1000 MB, Wide-Column sparse: 400 MB (60% reduction)

Cassandra Architecture - Distributed by Design

Peer-to-peer: All nodes equal

- No primary-replica distinction

- Any node can handle any request

- Consistent hashing distributes row keys

Partitioning:

- Row key hashed to token (0 to 2^63-1)

- Token ring: Nodes own token ranges

- Replication factor N=3: Each row stored on 3 nodes

Write path:

Client sends write to any node (coordinator)

Coordinator determines replicas from hash(row_key)

Write sent to N=3 replica nodes

Coordinator waits based on consistency level:

- ONE: Wait for 1 acknowledgment (5ms)

- QUORUM: Wait for 2 of 3 (10ms, parallel writes)

- ALL: Wait for all 3 (30ms)

Write durability on each node:

Write arrives

↓

Commit log (sequential append, durable)

↓

Memtable (in-memory, fast)

↓

[Background: Flush memtable → SSTable on disk]Commit log ensures no data loss if node crashes

Read path:

- Query replicas (number based on consistency)

- If replicas disagree: Return latest (by timestamp)

- Background read repair reconciles replicas

Hash determines primary node, N consecutive nodes store replicas

Compound Primary Key - Partition and Clustering

Primary key = (partition key, clustering columns)

Partition key: Determines node placement (hash distribution)

Clustering columns: Sort order within partition (range queries)

Table definition:

sensor_id= partition key (which node)timestamp= clustering column (sort order)

Physical layout on Node 3:

Partition: sensor_id=42000

timestamp=2025-01-15T10:00:00, temp=22.5, humidity=45

timestamp=2025-01-15T10:01:00, temp=22.6, humidity=46

timestamp=2025-01-15T10:02:00, temp=22.4, humidity=45

... (sorted by timestamp)

Partition: sensor_id=42001

timestamp=2025-01-15T10:00:00, temp=19.5, humidity=50

...Efficient query (uses partition key + clustering):

Single node, sequential read of 60 rows

Denormalization Required - No JOINs

Cassandra has no JOIN operation

Data for query must exist in single partition

Relational approach (JOINs):

-- users table

CREATE TABLE users (

user_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100),

email VARCHAR(100)

);

-- activities table

CREATE TABLE activities (

activity_id INT PRIMARY KEY,

user_id INT,

activity_type VARCHAR(50),

timestamp TIMESTAMP,

details TEXT

);

-- Query with JOIN

SELECT a.*, u.name

FROM activities a

JOIN users u ON a.user_id = u.user_id

WHERE a.timestamp > NOW() - INTERVAL '24 hours';Cassandra approach (denormalized):

Query:

Single partition, no JOIN

Update cost:

- User name changes → update all activity records

- User with 10,000 activities: 10,000 updates

- Trade-off: Query simplicity for update complexity

Acceptable when reads >> writes (activity log read 1000×, name changes rarely)

Multiple Query Patterns - Multiple Tables

Cannot optimize single table for multiple partition keys

Solution: Duplicate data in tables with different primary keys

Query pattern 1: Posts by user (timeline)

Query pattern 2: Posts by tag (search)

CREATE TABLE posts_by_tag (

tag TEXT,

post_timestamp TIMESTAMP,

post_id UUID,

user_id INT, -- Duplicated

content TEXT, -- Duplicated

likes INT, -- Duplicated

PRIMARY KEY (tag, post_timestamp)

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (post_timestamp DESC);

-- Efficient: Single partition

SELECT * FROM posts_by_tag

WHERE tag = 'nosql'

LIMIT 20;Write path:

- Application writes to both tables

- Post with 5 tags: 1 write to posts_by_user + 5 writes to posts_by_tag

- Total: 6 writes for 1 post

Storage: 6× duplication for 5-tag post

Trade: Storage and write complexity for query performance

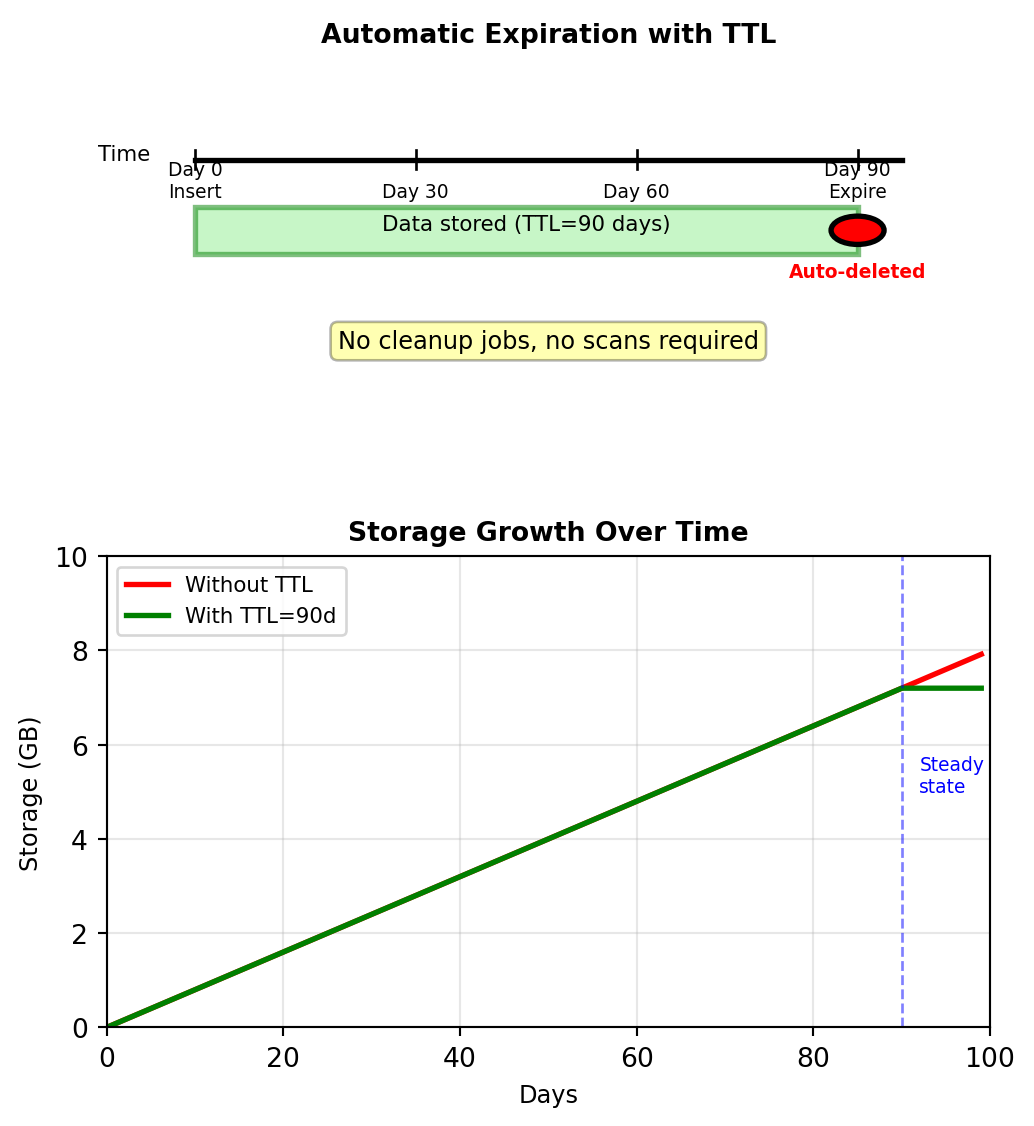

TTL - Automatic Data Expiration

Time-series data has natural lifecycle

Old data less valuable, must be removed

Manual deletion: Expensive

Scans entire table, expensive on billions of rows

TTL (time to live): Automatic expiration

Implementation:

- TTL stored as metadata with each column

- Compaction removes expired data during background merge

- Tombstone created at expiration (soft delete)

- No read-time overhead: Expired data not returned

Use cases:

- Monitoring data: 90-day retention

- Session data: 30-minute expiration

- Cache data: 5-minute expiration

- Rate limiting counters: Hourly expiration

Storage calculation:

- 10,000 sensors × 8,640 readings/day = 86.4M rows/day

- Without TTL: Unbounded growth

- With 90-day TTL: Steady state at 7.78B rows

Graph Databases

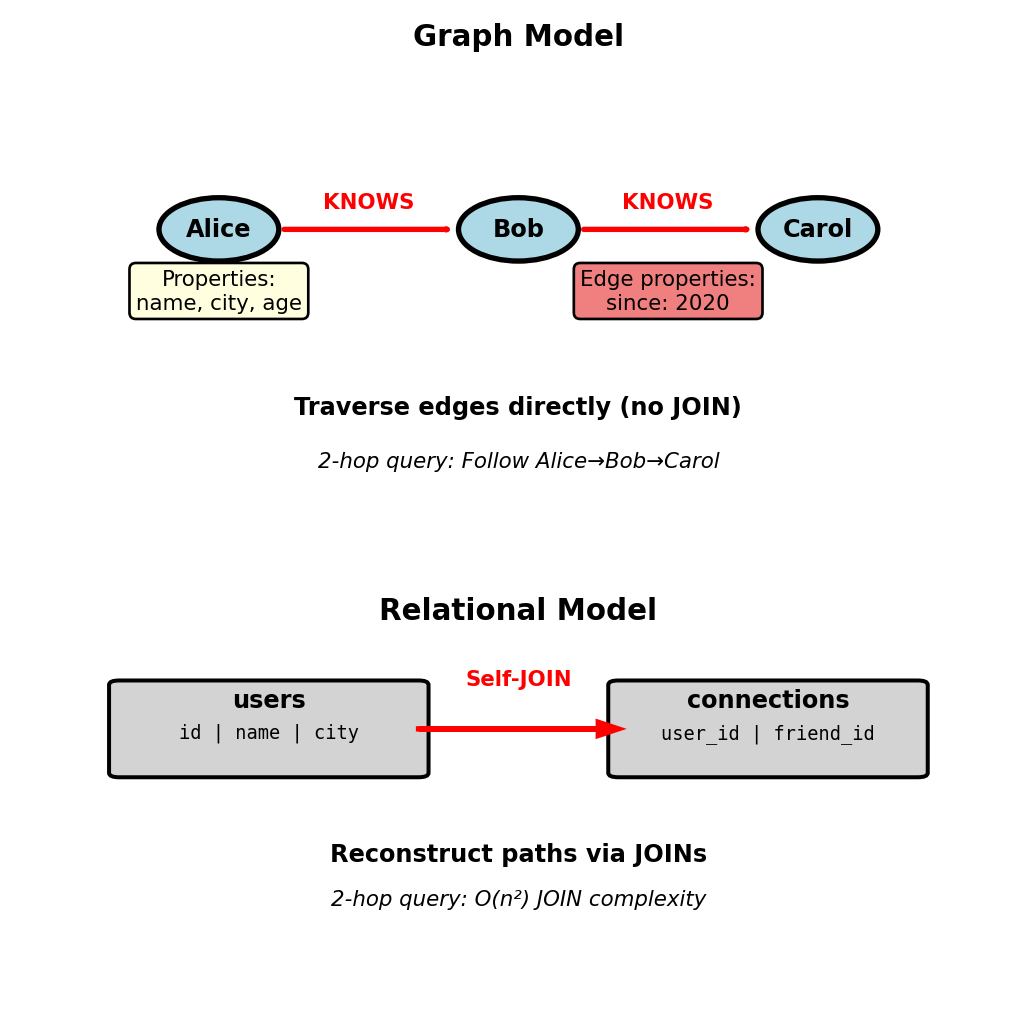

Graph Model - Nodes, Edges, Properties

Social network queries require expensive self-JOINs:

Graph model stores relationships directly:

- Nodes: Entities with properties

- Edges: Relationships between nodes, can have properties

- Query: Traverse edges, no JOIN operations

Example:

- Node: Person {id: 123, name: “Alice”, city: “Boston”}

- Edge: (Alice)-[:KNOWS {since: 2020}]->(Bob)

- Query “friends of friends” = follow 2 edges

Native graph databases store adjacency (pointers between nodes), not foreign keys

Path Traversal - Friends of Friends in Neo4j

Query: Find friends-of-friends who live in Boston

Cypher (Neo4j query language):

MATCH (me:Person {id: 123})-[:KNOWS]->(friend)

-[:KNOWS]->(fof:Person)

WHERE fof.city = 'Boston'

AND fof.id <> 123

RETURN fof.name, fof.cityPattern matching: (node)-[edge]->(node) describes path structure

Relational equivalent:

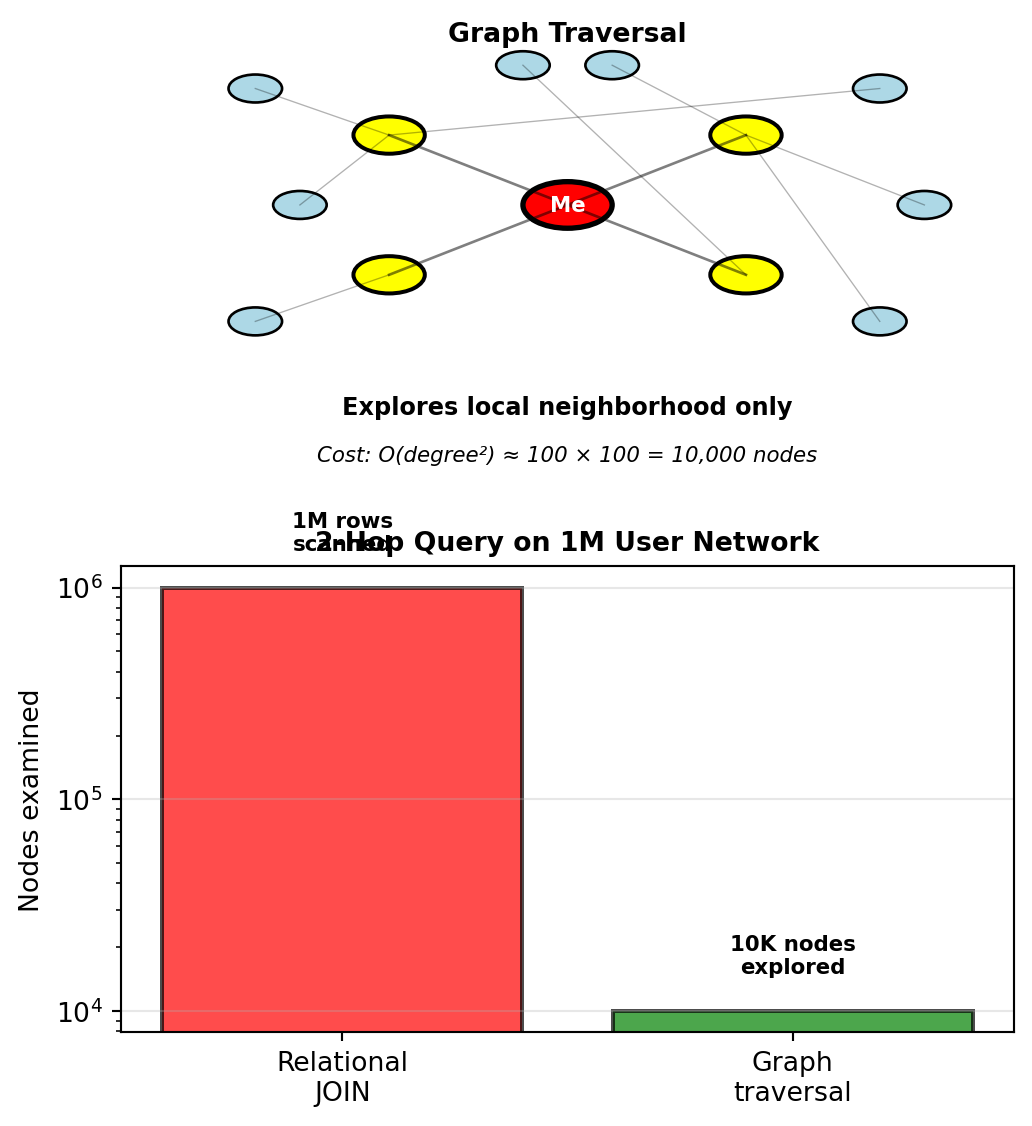

Performance difference:

- Relational: O(n²) - must JOIN entire connections table twice

- Graph: O(degree²) - follows edges from specific node

For node with 100 friends, each friend has 100 friends:

- Graph: Explores ~10,000 nodes

- SQL: Must process millions of rows (even with indexes)

Graph complexity depends on local structure (node degree), not global table size

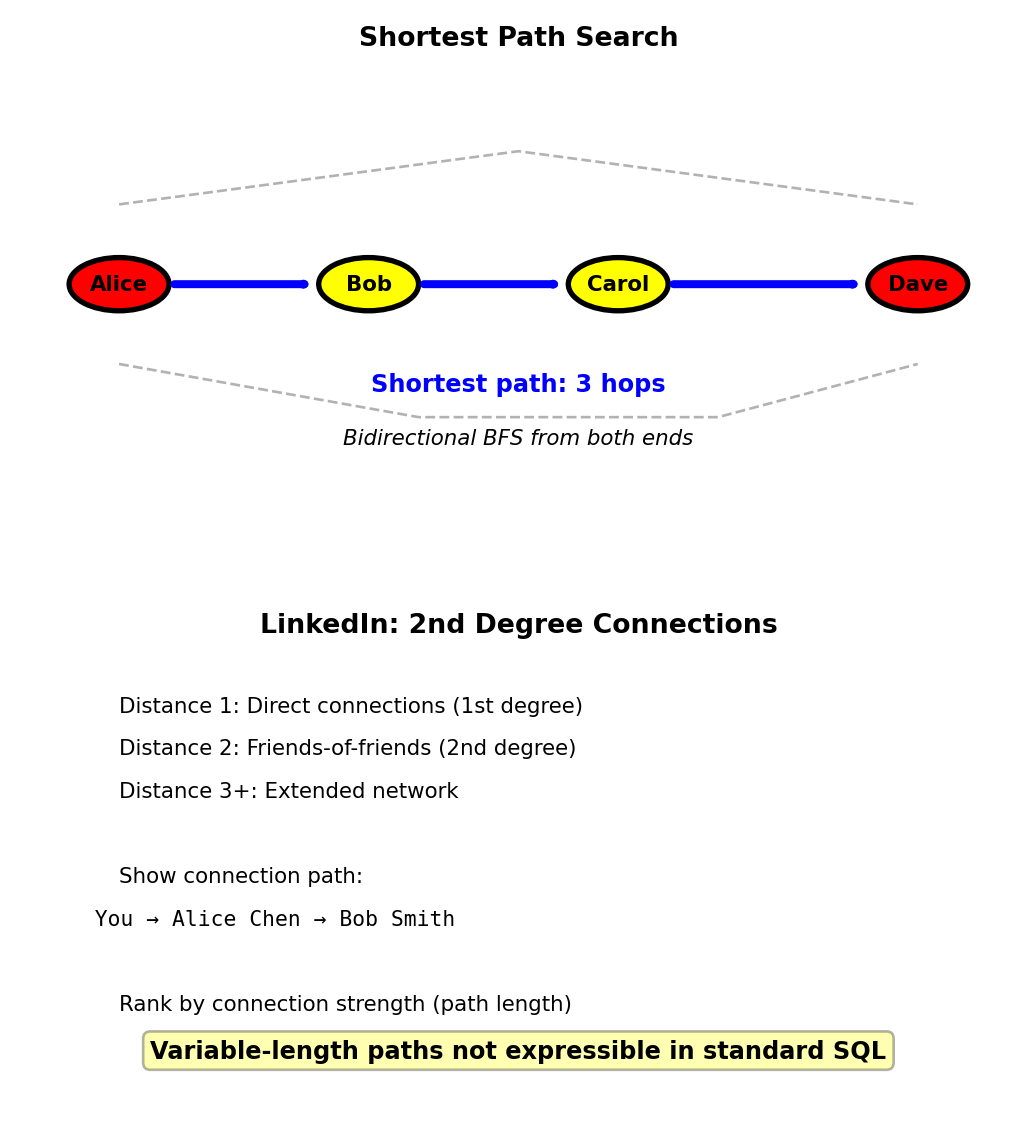

Variable-Length Paths - Connection Distance

Query: How many hops separate two people? Find shortest path.

Cypher:

MATCH path = shortestPath(

(a:Person {id: 123})-[:KNOWS*]-(b:Person {id: 789})

)

RETURN length(path)[:KNOWS*]matches 1 or more KNOWS edges- Finds shortest connection: 2 hops, 3 hops, etc.

- Bidirectional breadth-first search from both ends

Return path details:

RETURN [node IN nodes(path) | node.name] AS connection_path

-- Result: ["Alice", "Bob", "Carol", "Dave"]SQL equivalent:

- Requires recursive CTE (PostgreSQL, Oracle)

- Limited depth, complex syntax

- Poor performance on large graphs

WITH RECURSIVE paths AS (

SELECT user_id, friend_id, 1 AS depth,

ARRAY[user_id, friend_id] AS path

FROM connections

WHERE user_id = 123

UNION ALL

SELECT p.user_id, c.friend_id, p.depth + 1,

p.path || c.friend_id

FROM paths p

JOIN connections c ON p.friend_id = c.user_id

WHERE p.depth < 6

AND NOT c.friend_id = ANY(p.path)

)

SELECT MIN(depth) FROM paths WHERE friend_id = 789;

Use case: LinkedIn shows connection path and degree of separation

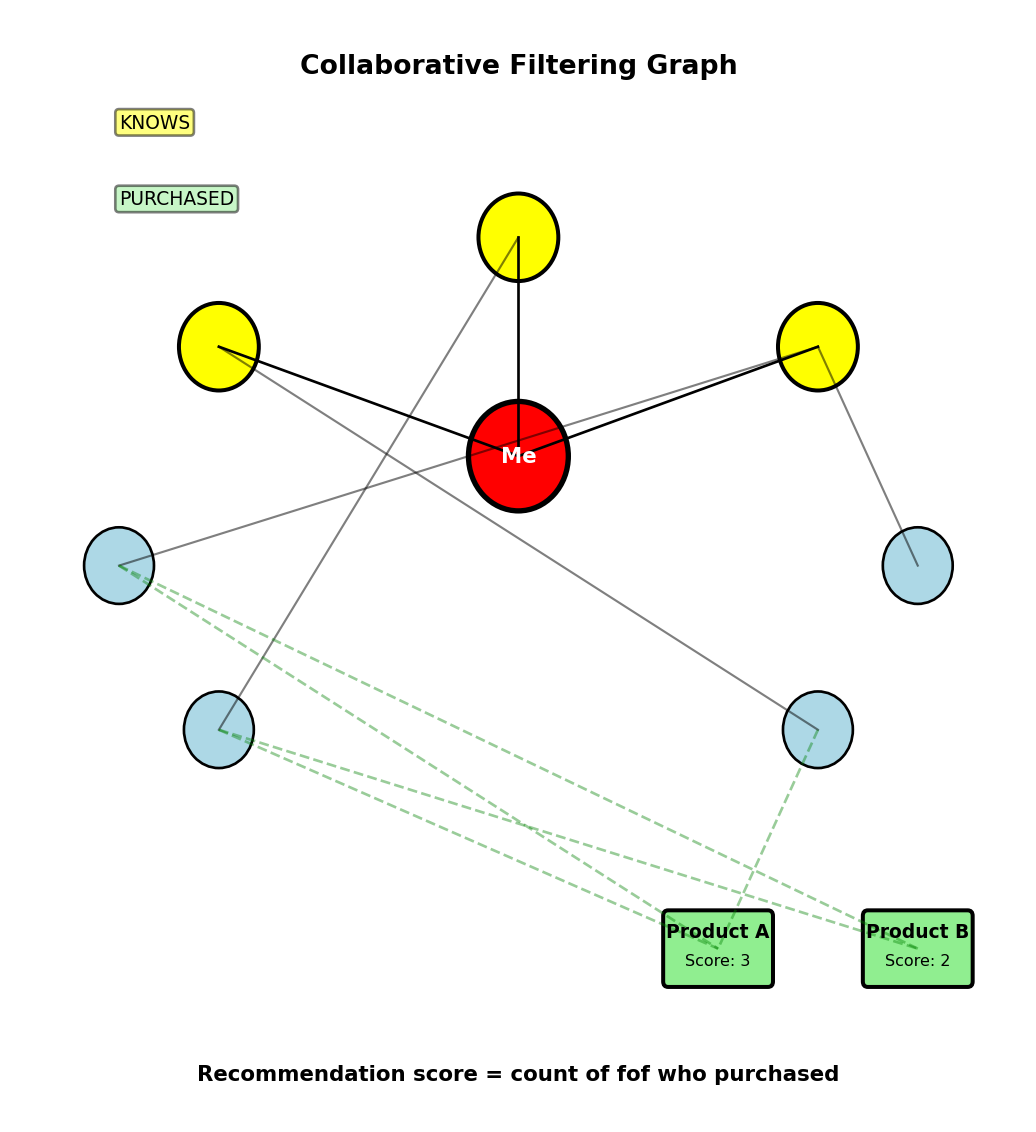

Recommendation - Collaborative Filtering

Problem: Recommend products based on friend purchases

Query: Products bought by friends-of-friends but not by me or my direct friends

MATCH (me:Person {id: 123})-[:KNOWS*1..2]->(friend)

MATCH (friend)-[:PURCHASED]->(product:Product)

WHERE NOT (me)-[:PURCHASED]->(product)

AND NOT (me)-[:KNOWS]->()-[:PURCHASED]->(product)

RETURN product.name, COUNT(friend) as recommendation_score

ORDER BY recommendation_score DESC

LIMIT 10Query breakdown:

[:KNOWS*1..2]= 1 or 2 hops (friends + friends-of-friends)- Find products purchased by anyone in that set

- Filter out: products I’ve bought

- Filter out: products my direct friends bought

- Count recommendations from multiple sources

Performance:

- Traverses ~10,000 relationships (100 friends × 100 fof)

- Filters and aggregates during traversal

- Returns top 10 products

- Completes in ~50ms

Relational equivalent:

- 3 self-JOINs on connections table

- JOIN with purchases table

- Multiple subqueries for filtering

- Scans millions of rows

- Completes in ~5 seconds

Results:

- Product A: 3 friends-of-friends purchased → score 3

- Product B: 2 friends-of-friends purchased → score 2

Relational requires 3 self-JOINs + product JOIN + filtering subqueries

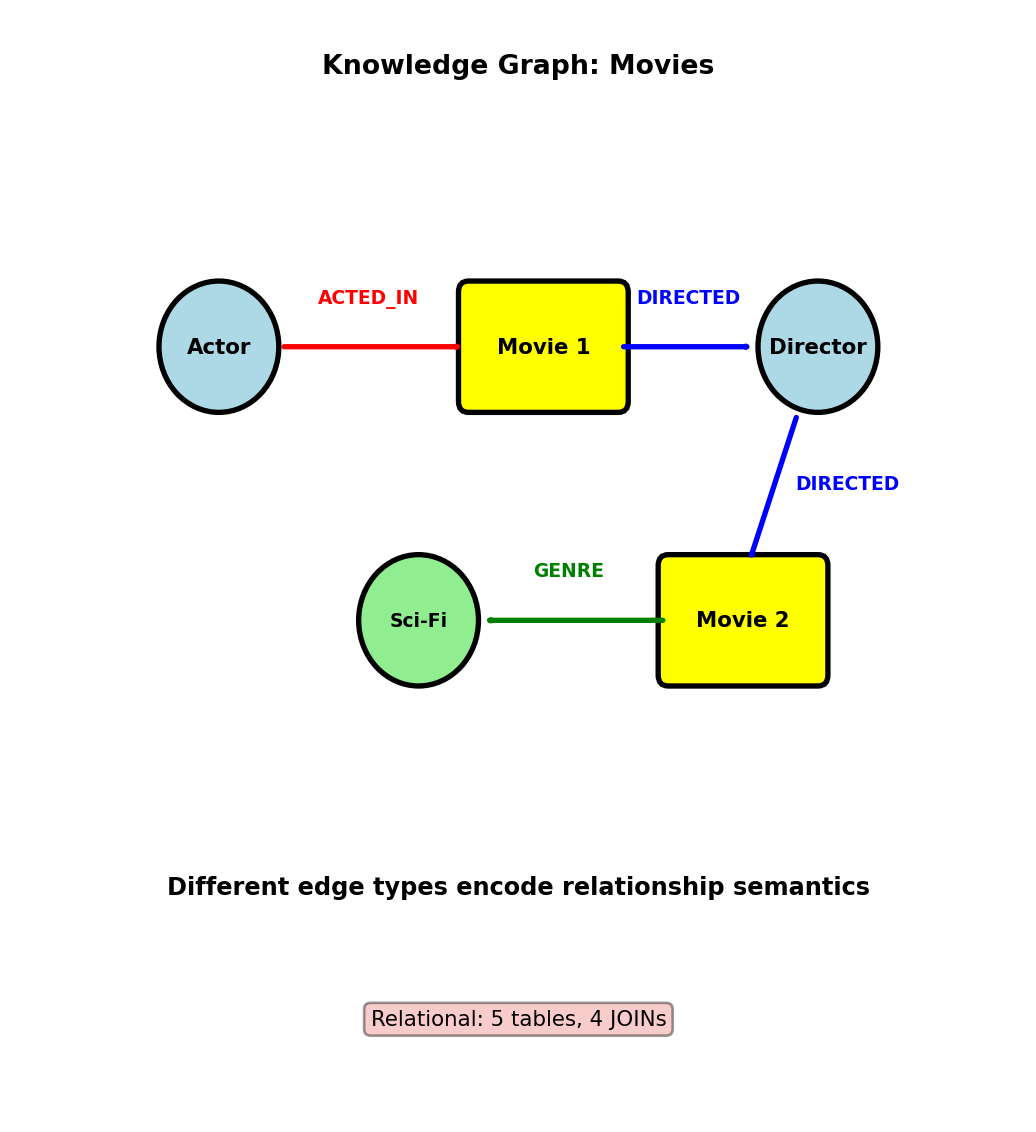

Knowledge Graphs - Multi-Type Relationships

Movie database with heterogeneous relationships:

Schema (property graph model):

Nodes:

Person (name, birth_year)

Movie (title, year, rating)

Genre (name)

Edges:

(Person)-[:ACTED_IN {role: "Batman"}]->(Movie)

(Person)-[:DIRECTED]->(Movie)

(Movie)-[:BELONGS_TO_GENRE]->(Genre)Query: Actors who worked with directors who directed Sci-Fi movies

MATCH (actor:Person)-[:ACTED_IN]->(m1:Movie)

<-[:DIRECTED]-(director:Person)

MATCH (director)-[:DIRECTED]->(m2:Movie)

-[:BELONGS_TO_GENRE]->(g:Genre {name: 'Sci-Fi'})

WHERE m1 <> m2

RETURN DISTINCT actor.name, director.name, m2.titleQuery breakdown:

- Find actor-director collaborations

- Find other movies directed by same director

- Filter for Sci-Fi genre

- Different relationship types (ACTED_IN, DIRECTED, BELONGS_TO_GENRE)

Relational equivalent:

- 5 tables: people, movies, genres, movie_actors, movie_directors, movie_genres

- 4 JOINs with filtering on relationship types

- Complex foreign key navigation

Heterogeneous graphs: Multiple node types, multiple edge types with different semantics

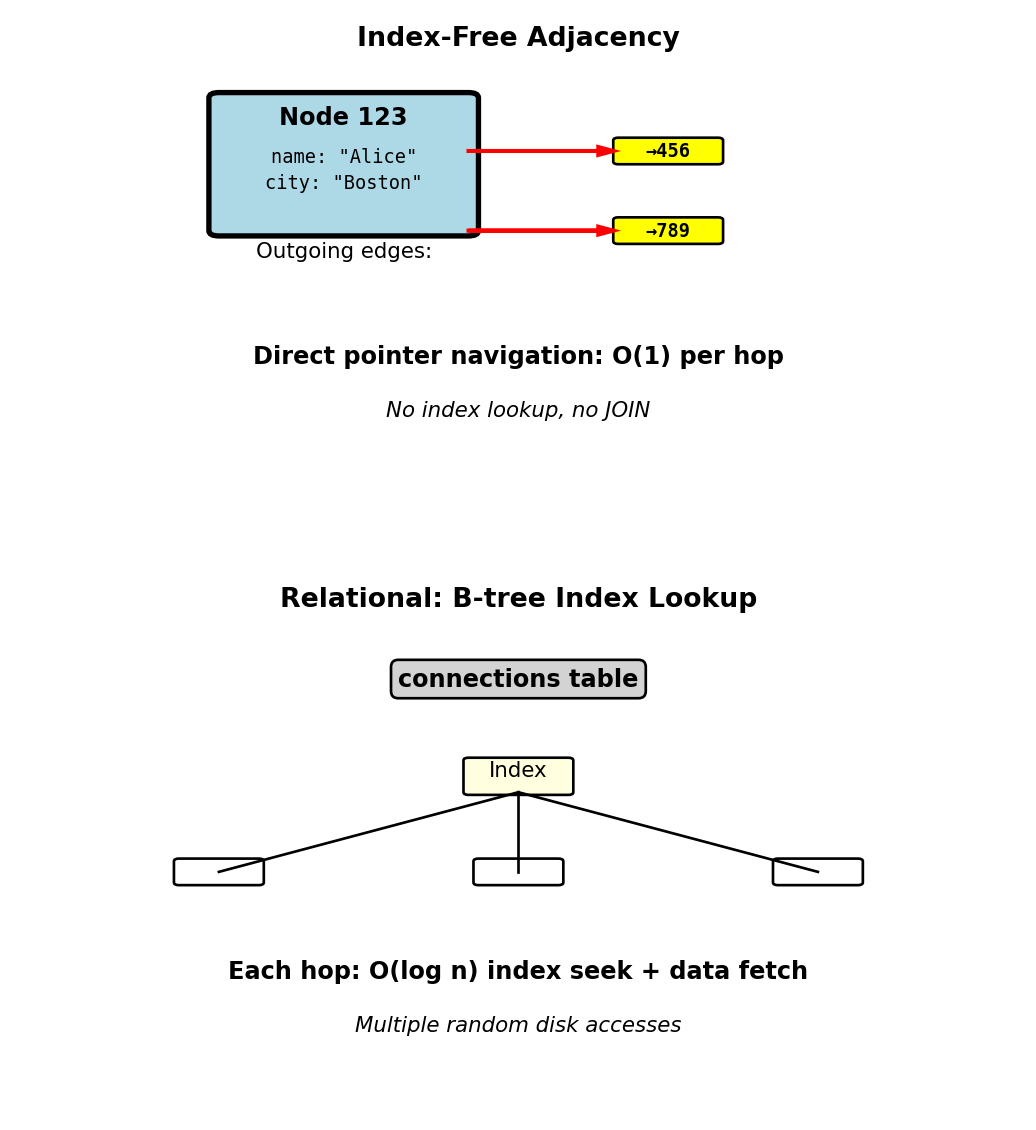

Property Graph Storage - Index-Free Adjacency

Native graph databases store direct pointers between nodes:

Conceptual storage structure:

Node 123 (Alice):

properties: {name: "Alice", city: "Boston"}

outgoing_edges: [ptr→456, ptr→789]

incoming_edges: [ptr→234]

Node 456 (Bob):

properties: {name: "Bob", city: "NYC"}

outgoing_edges: [ptr→123, ptr→999]

incoming_edges: [ptr→123, ptr→555]Traversal cost:

- Follow edge: O(1) pointer dereference

- No index lookup required

- No JOIN operation

- Cache-efficient: Related nodes stored nearby on disk

Relational comparison:

- JOIN requires: Index lookup O(log n) or table scan O(n)

- Even with B-tree indexes: Multiple random disk seeks

- Each hop: Seek to index, seek to data

- Graph: Sequential read following pointers

Physical layout:

- Nodes clustered by locality

- Edges stored with source node

- Adjacency list per node

- Disk reads proportional to result size, not table size

Graph databases optimize for traversal, relational optimizes for joins

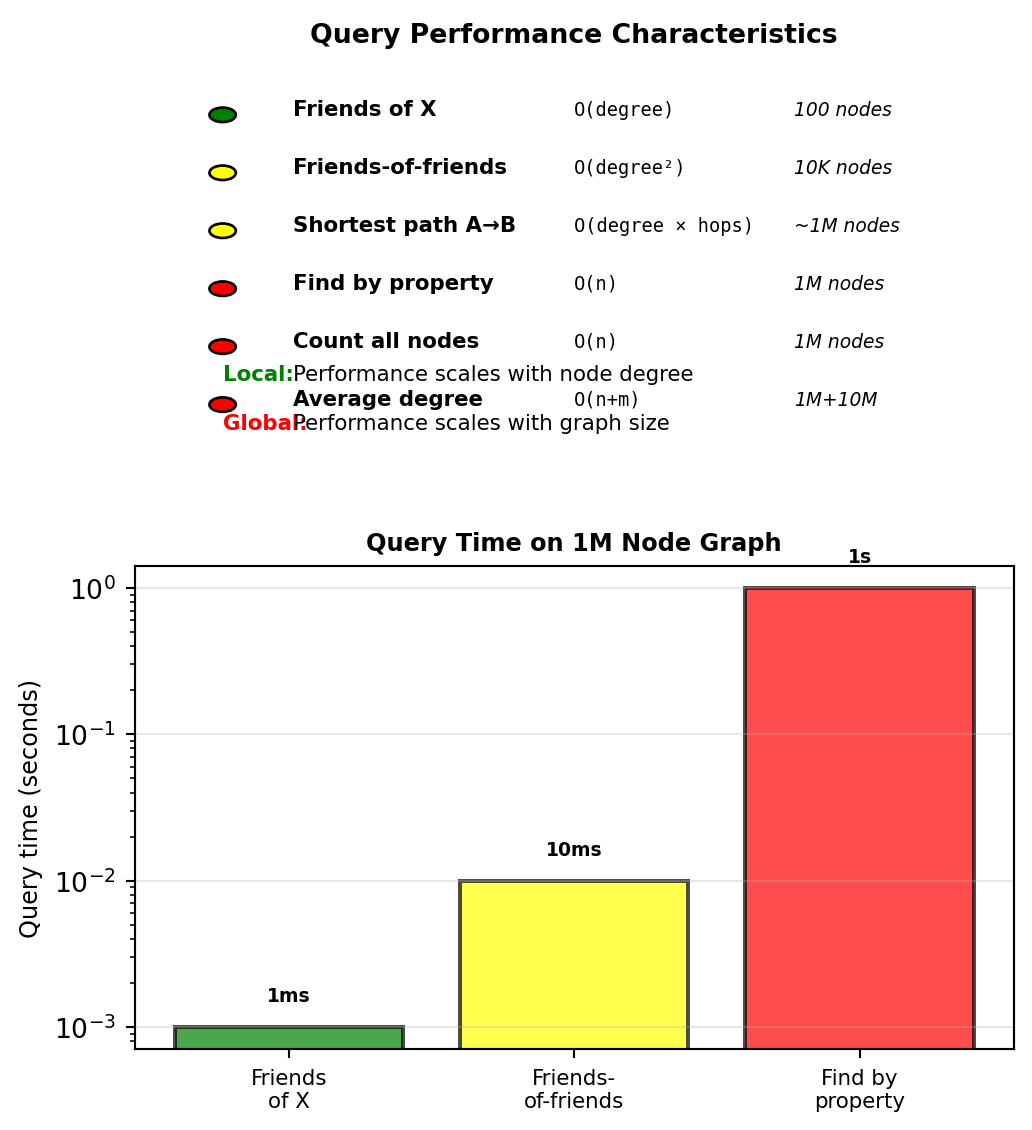

Graph Query Complexity - Local vs Global

Fast queries (local traversal):

Performance independent of graph size, depends on local structure:

“Friends of person X”: O(degree)

- Node with 100 friends: examine 100 nodes

- Graph size irrelevant

“Friends-of-friends of X”: O(degree²)

- 100 friends, each with 100 friends: examine 10,000 nodes

- Still independent of total graph size

“Shortest path between A and B”: O(degree × hops)

- 6 degrees of separation: explore ~1,000,000 nodes

- But only if path exists

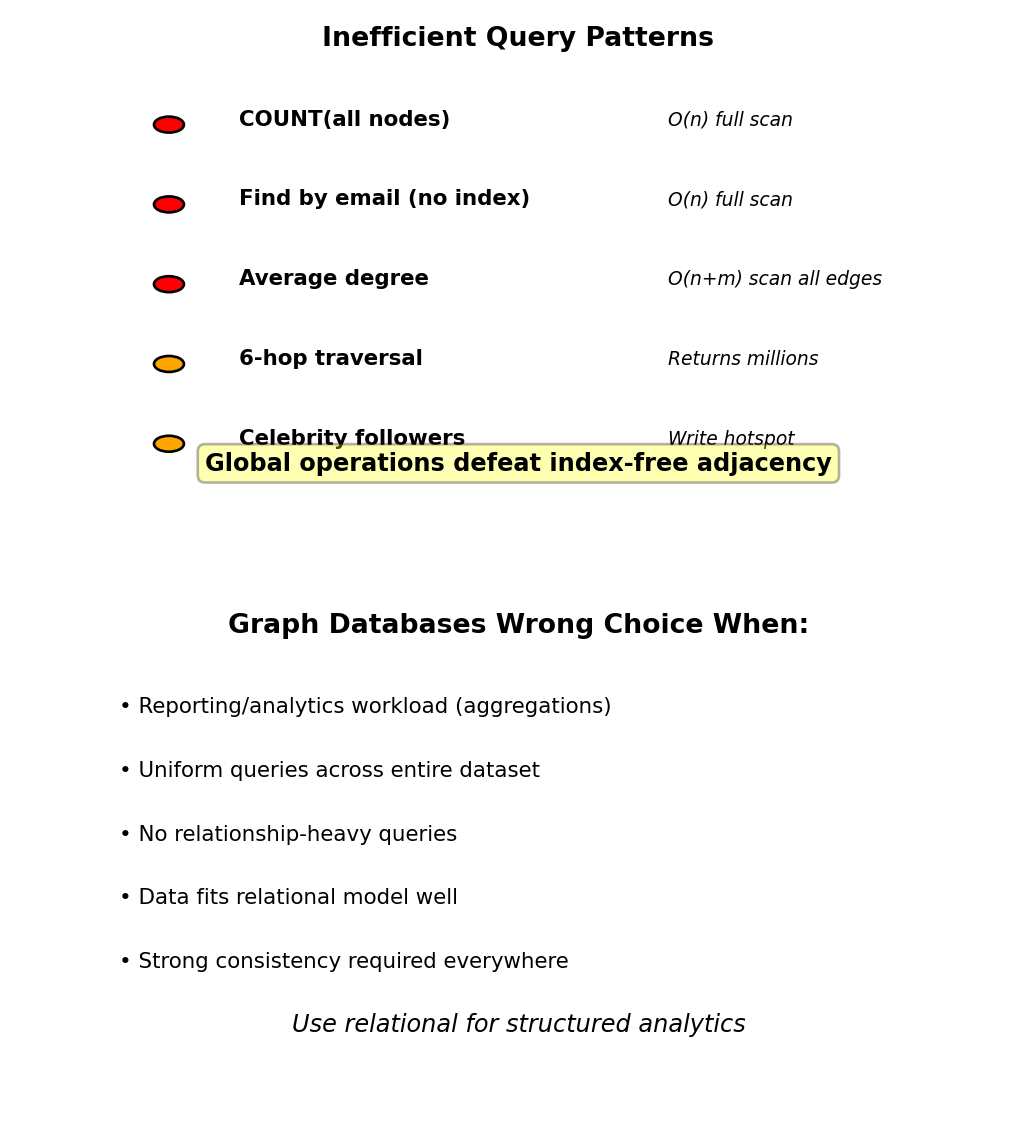

Slow queries (global aggregation):

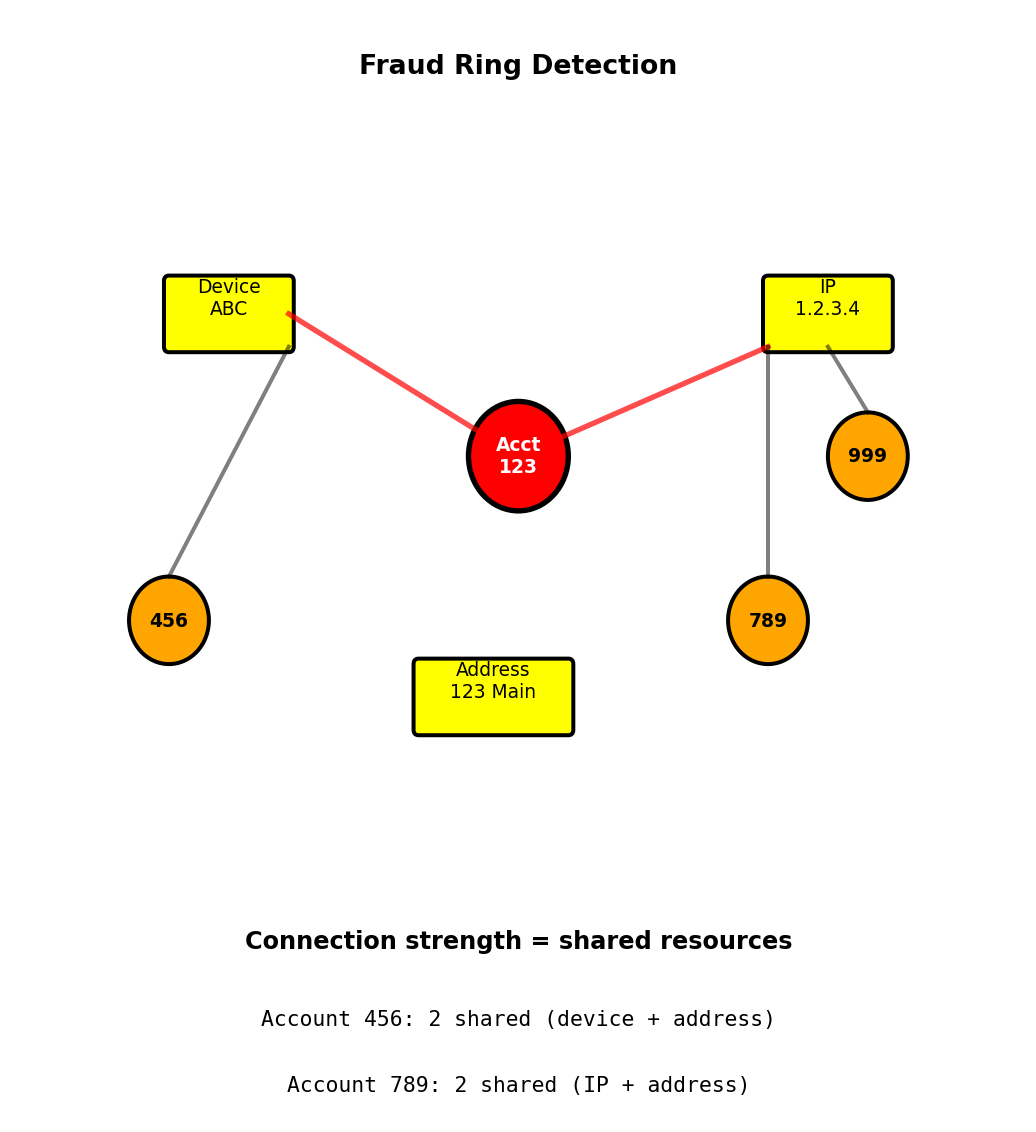

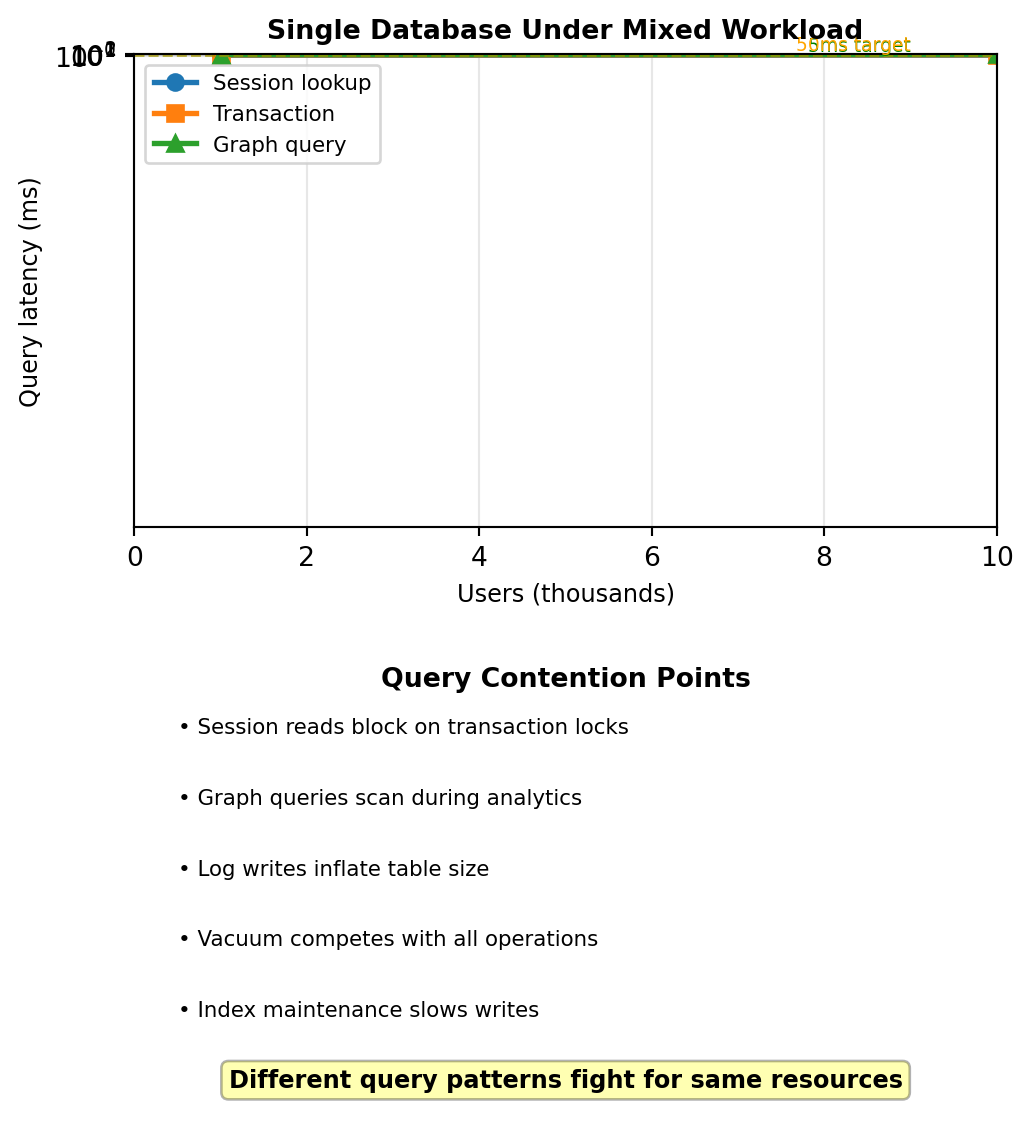

Must scan entire graph: