Cloud Patterns: Storage, Serverless, and Coordination

EE 547 - Unit 9

Fall 2025

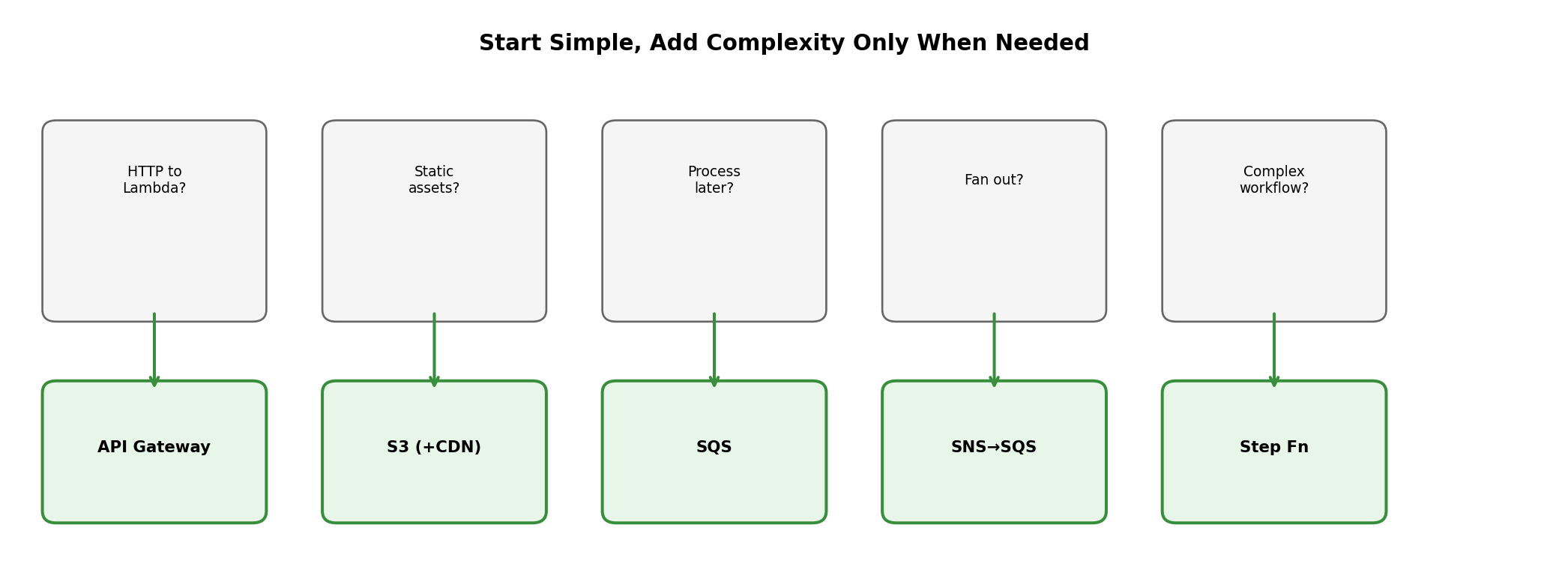

Outline

Storage and Compute

- Instance storage ephemeral; EBS persists

- S3: HTTP API, not filesystem

- Key design determines query efficiency

- Lambda: function invocation, not process lifecycle

- Cold starts vs warm execution environments

- Memory setting controls CPU allocation

- SQS decouples producers from consumers

- Visibility timeout and dead letter queues

Integration and Architecture

- API Gateway bridges HTTP to Lambda

- CloudFront caches at edge locations

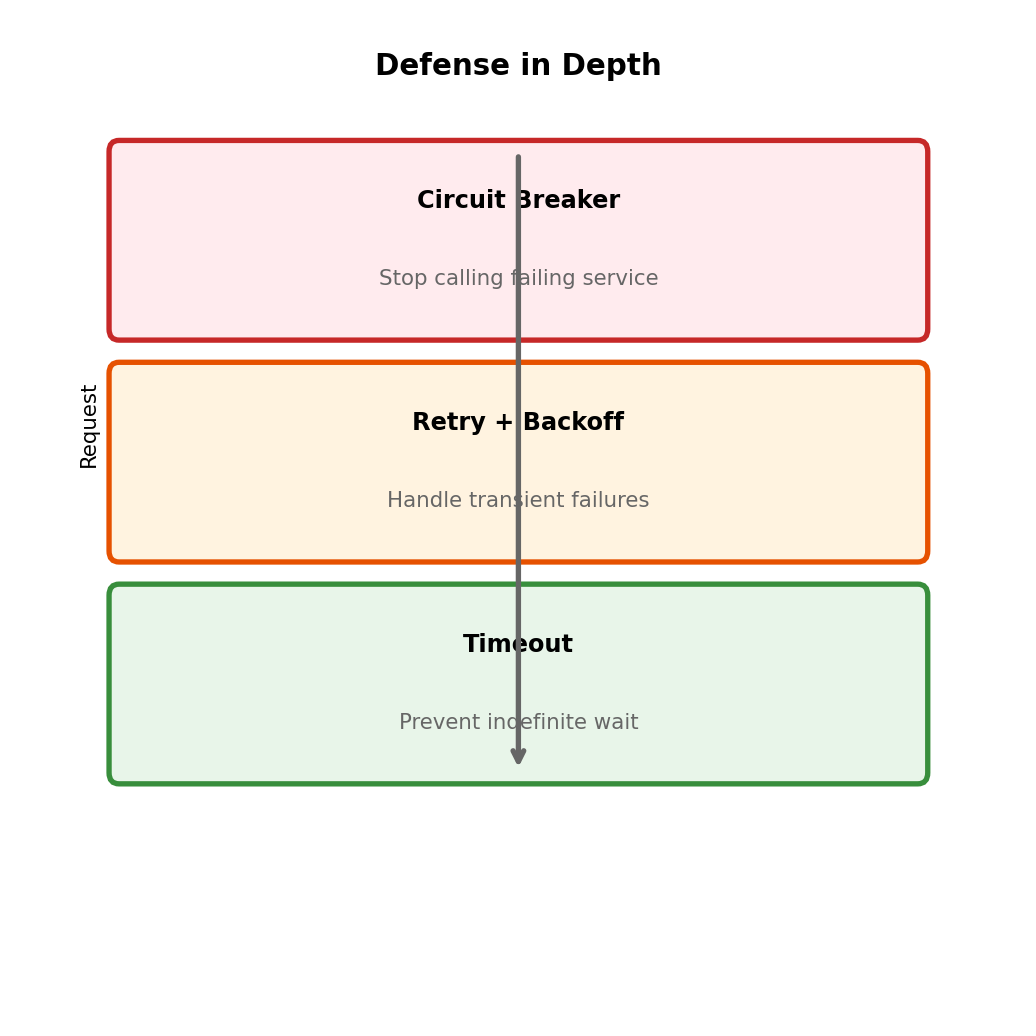

- Resilience: retry, backoff, circuit breaker

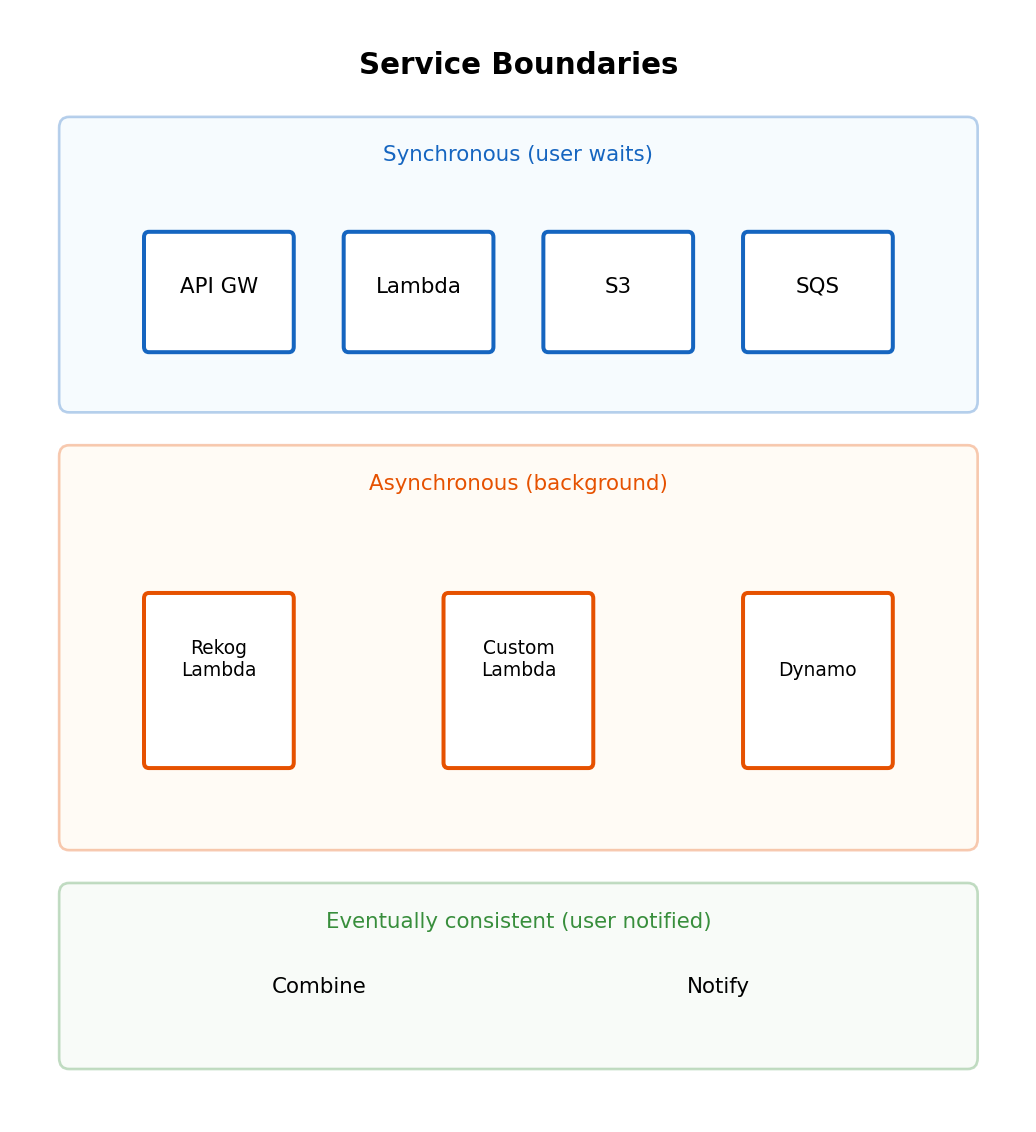

- Decomposition into service boundaries

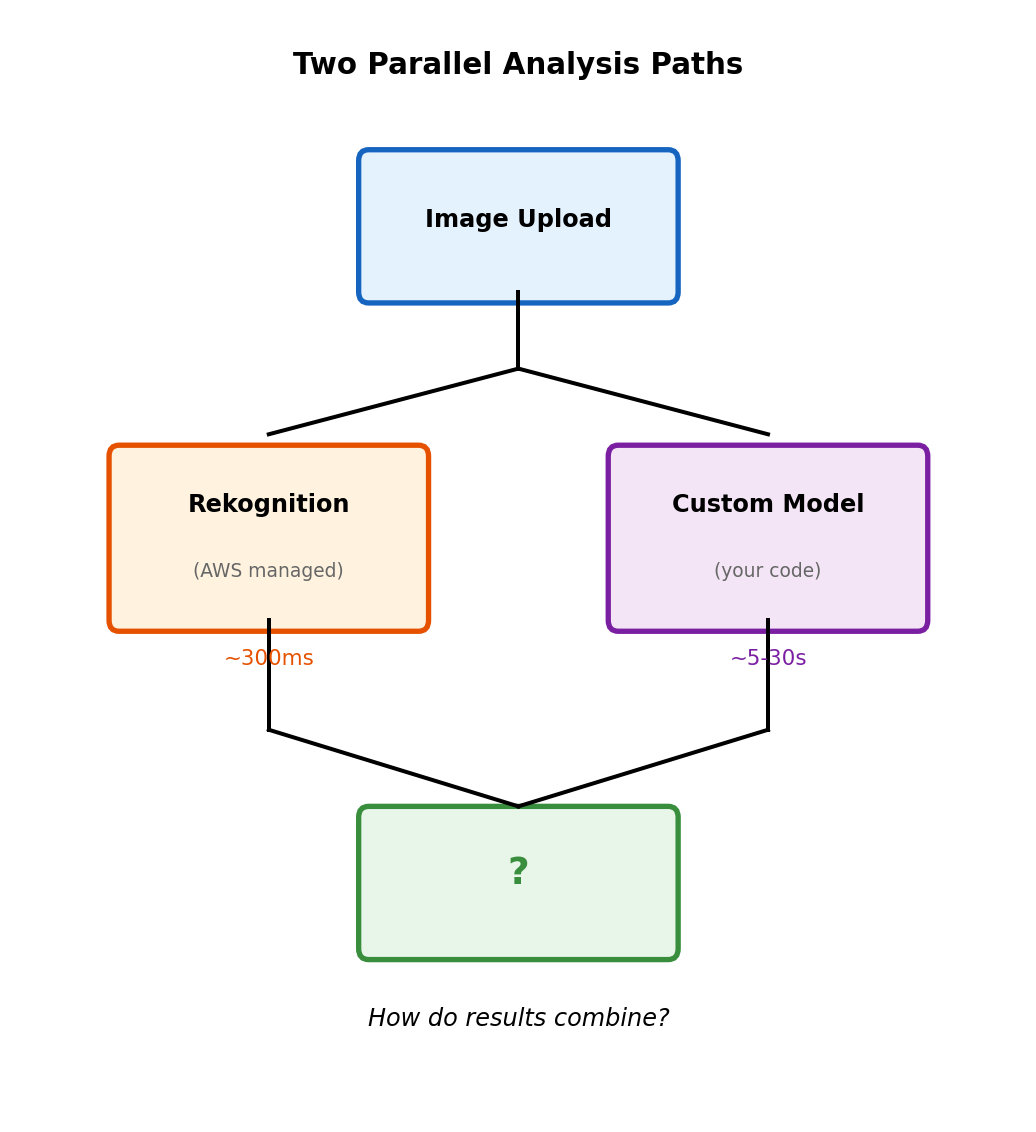

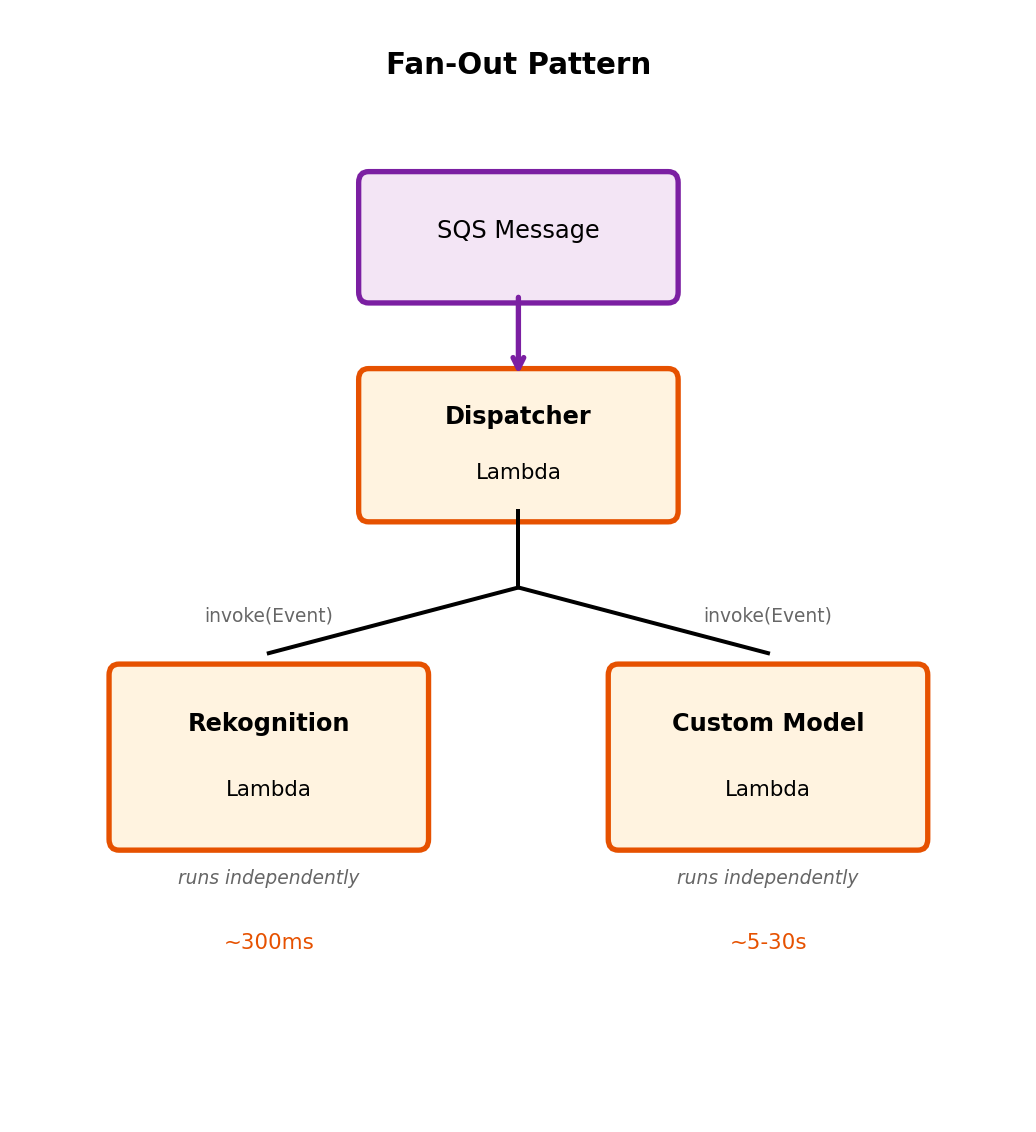

- Fan-out to parallel processing paths

- Coordination when multiple async tasks complete

Cloud Storage Models

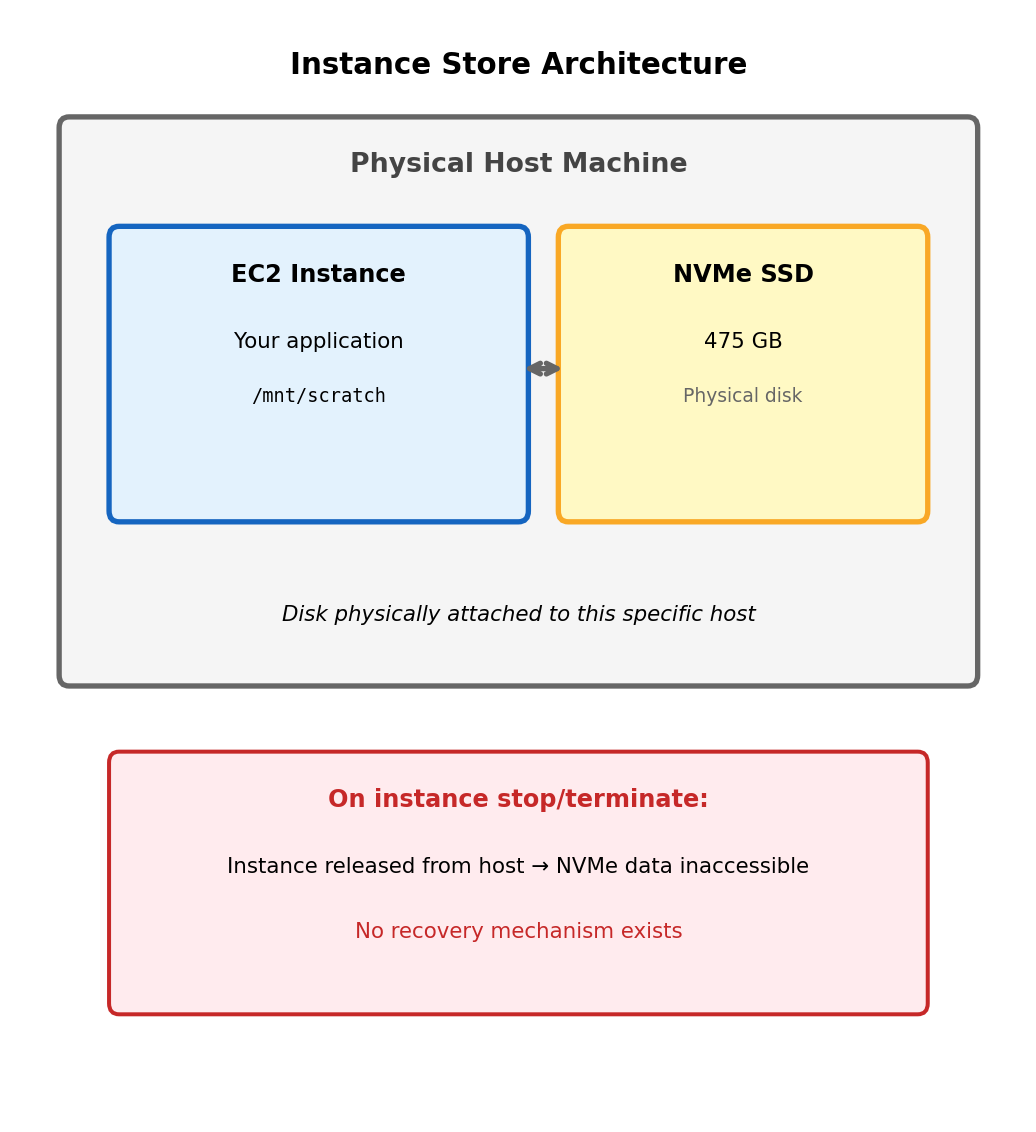

Instance Storage Does Not Survive Instance Lifecycle

Instance store: Physical disk attached to host hardware

# Check available block devices on EC2 instance

$ lsblk

NAME SIZE TYPE MOUNTPOINT

nvme0n1 8G disk / # Root (EBS)

nvme1n1 475G disk # Instance store (NVMe)Instance store provides highest performance - directly attached NVMe SSDs with ~100k IOPS and sub-millisecond latency.

Data loss occurs on:

- Instance stop (not just terminate)

- Instance termination

- Underlying hardware failure

- Spot instance reclamation

- Host maintenance events

The storage is physically part of the host machine. When the instance moves to different hardware (or ceases to exist), the disk does not follow.

Cannot detach or snapshot. Unlike network-attached storage, there is no mechanism to preserve instance store contents independently of the instance.

Appropriate for: Scratch space, temporary processing files, caches that can be rebuilt. Not appropriate for any data that must survive instance lifecycle.

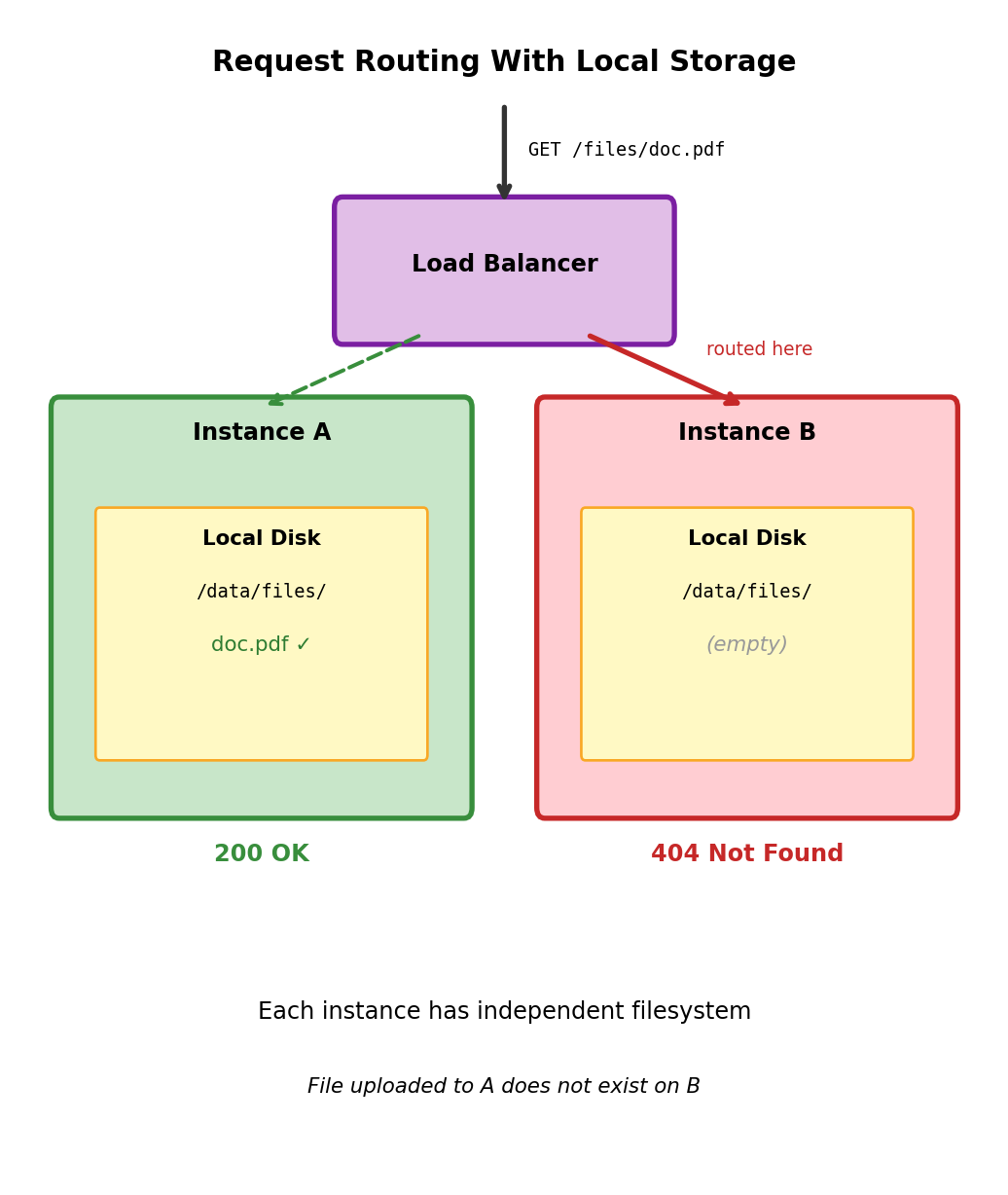

Horizontal Scaling Breaks Local Storage Assumptions

Single instance architecture

All requests handled by same instance, all file operations see same filesystem state.

Multiple instance architecture

Load balancer distributes requests. Each instance has independent local filesystem.

Instance A Instance B

├── /data/models/ ├── /data/models/

│ └── classifier.pkl │ └── (empty)

└── /data/uploads/ └── /data/uploads/

└── file1.pdf └── (empty)Request uploads file to Instance A. Subsequent request routed to Instance B. File does not exist - FileNotFoundError.

Model deployed to Instance A. Instance B cannot serve predictions - model not present.

Fundamental issue: Local filesystem is instance-scoped, but application logic assumes shared state across all request handlers.

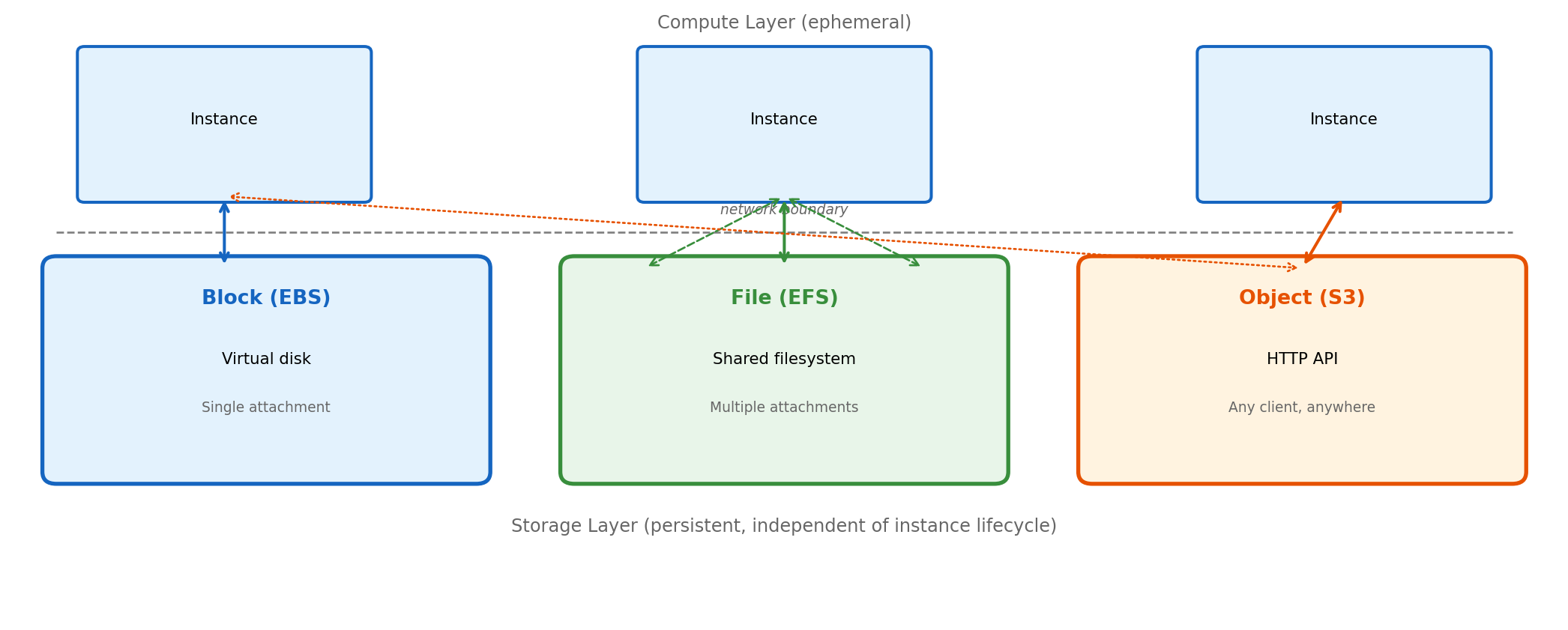

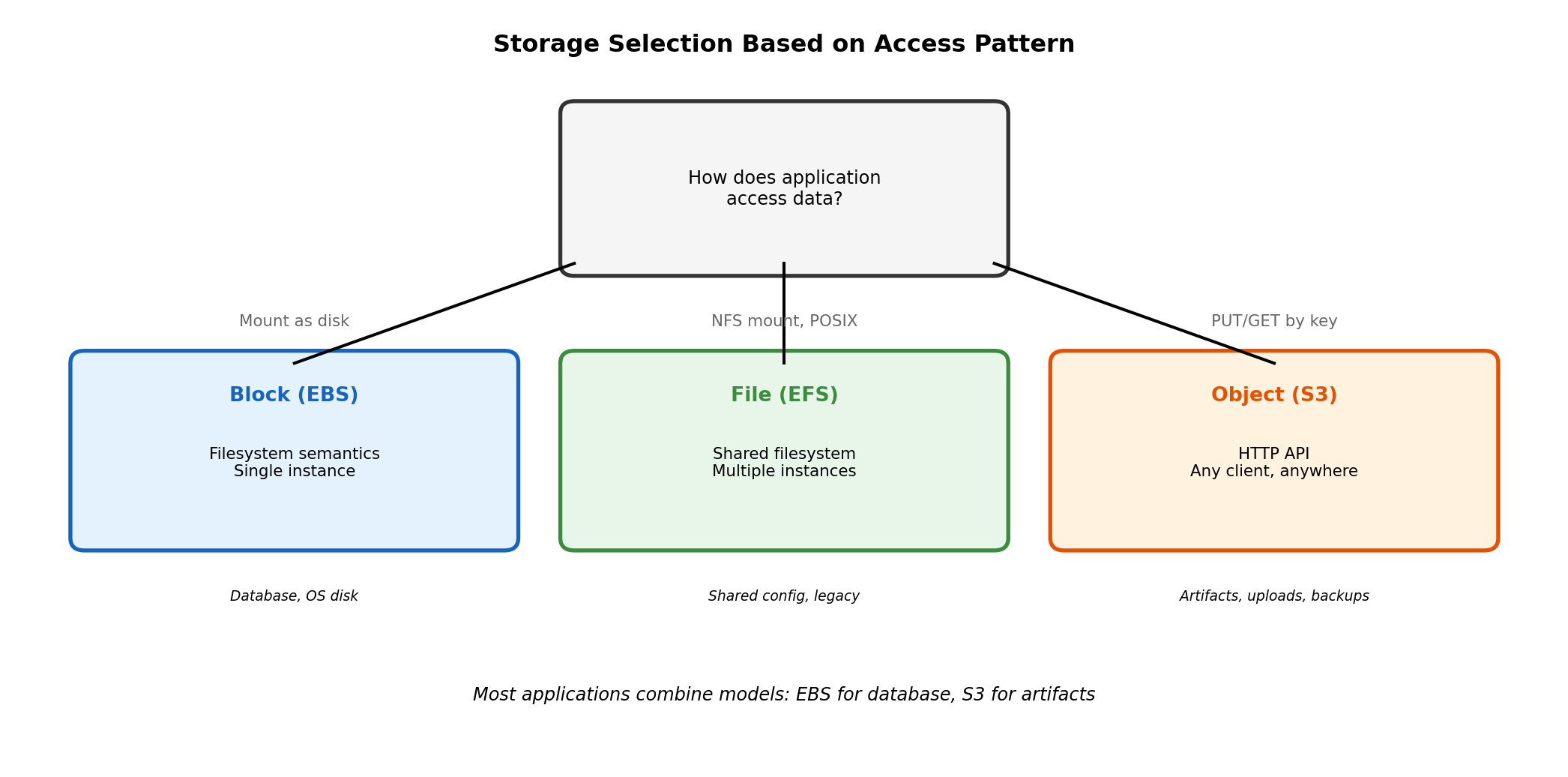

Storage Must Exist Independent of Compute Instances

Three abstractions provide instance-independent storage with different access models:

Block storage presents a virtual disk device. Instance mounts it as filesystem, uses standard file operations. One instance attachment at a time (with limited exceptions).

File storage provides shared filesystem via network protocol (NFS). Multiple instances mount simultaneously, see same files, coordinate via filesystem semantics.

Object storage exposes HTTP API for storing and retrieving blobs by key. No filesystem abstraction - operations are PUT, GET, DELETE over HTTPS. Accessible from any network location.

Each model trades capabilities for constraints. Selection depends on how application accesses data.

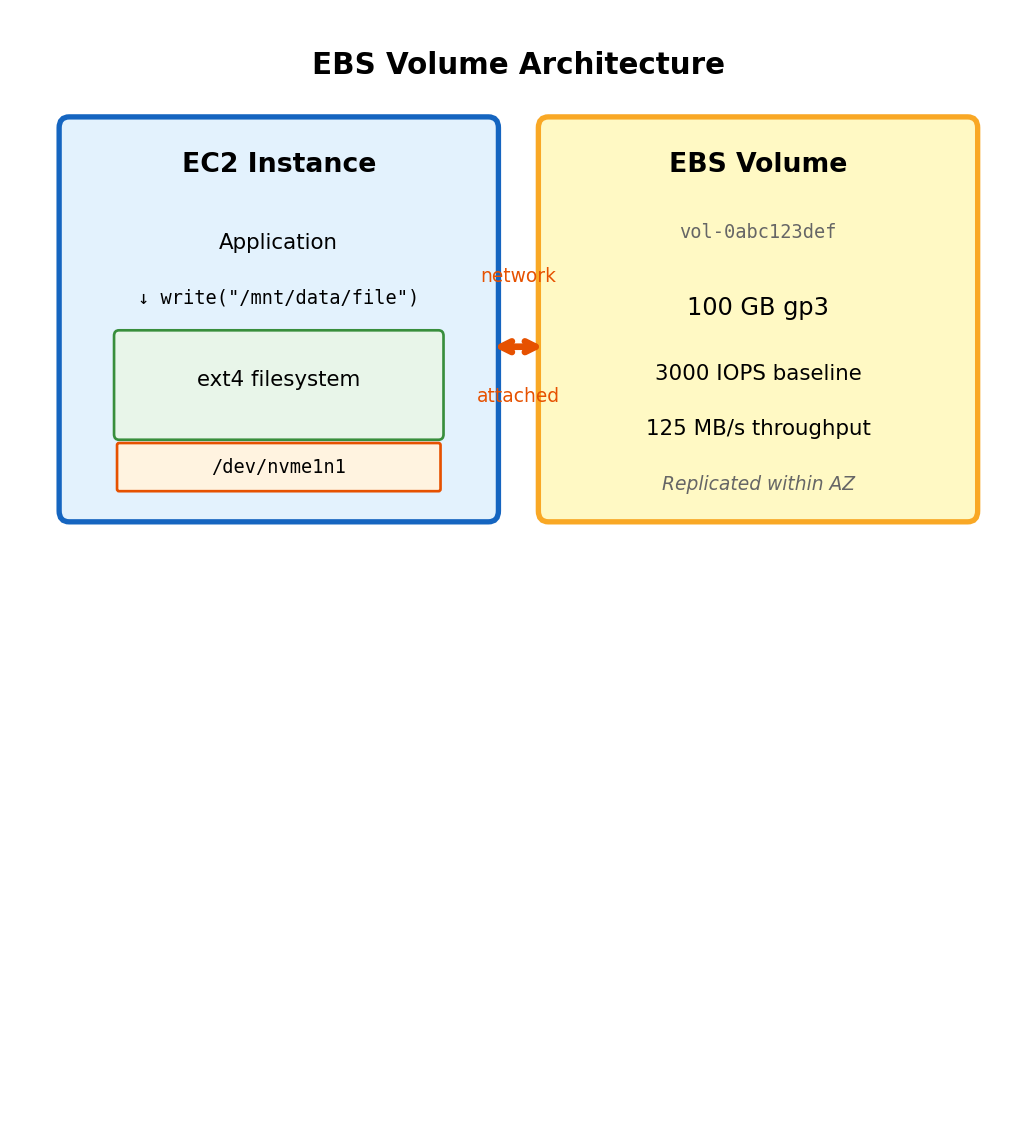

Block Storage Provides Virtual Disk Device

EBS volume appears as block device to instance

# List block devices - EBS volume appears as nvme device

$ lsblk

NAME SIZE TYPE

nvme0n1 8G disk # Root volume

└─nvme0n1p1 8G part /

nvme1n1 100G disk # Attached EBS volumeThe volume is a raw block device - bytes addressable by sector. No filesystem until you create one.

Preparing new volume for use:

# Create partition table (GPT for volumes > 2TB)

$ sudo parted /dev/nvme1n1 mklabel gpt

# Create single partition spanning volume

$ sudo parted /dev/nvme1n1 mkpart primary 0% 100%

# Create ext4 filesystem on partition

$ sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/nvme1n1p1

# Create mount point and mount

$ sudo mkdir /mnt/data

$ sudo mount /dev/nvme1n1p1 /mnt/data

# Verify

$ df -h /mnt/data

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/nvme1n1p1 98G 61M 93G 1% /mnt/dataAfter mounting, /mnt/data behaves as normal directory. Application reads and writes files without awareness of underlying EBS volume.

EBS characteristics:

- Persists independently of instance (survives stop/terminate)

- Snapshots to S3 for backup and replication

- Resizable while attached (extend filesystem after)

- Latency: sub-millisecond (network-attached, same AZ)

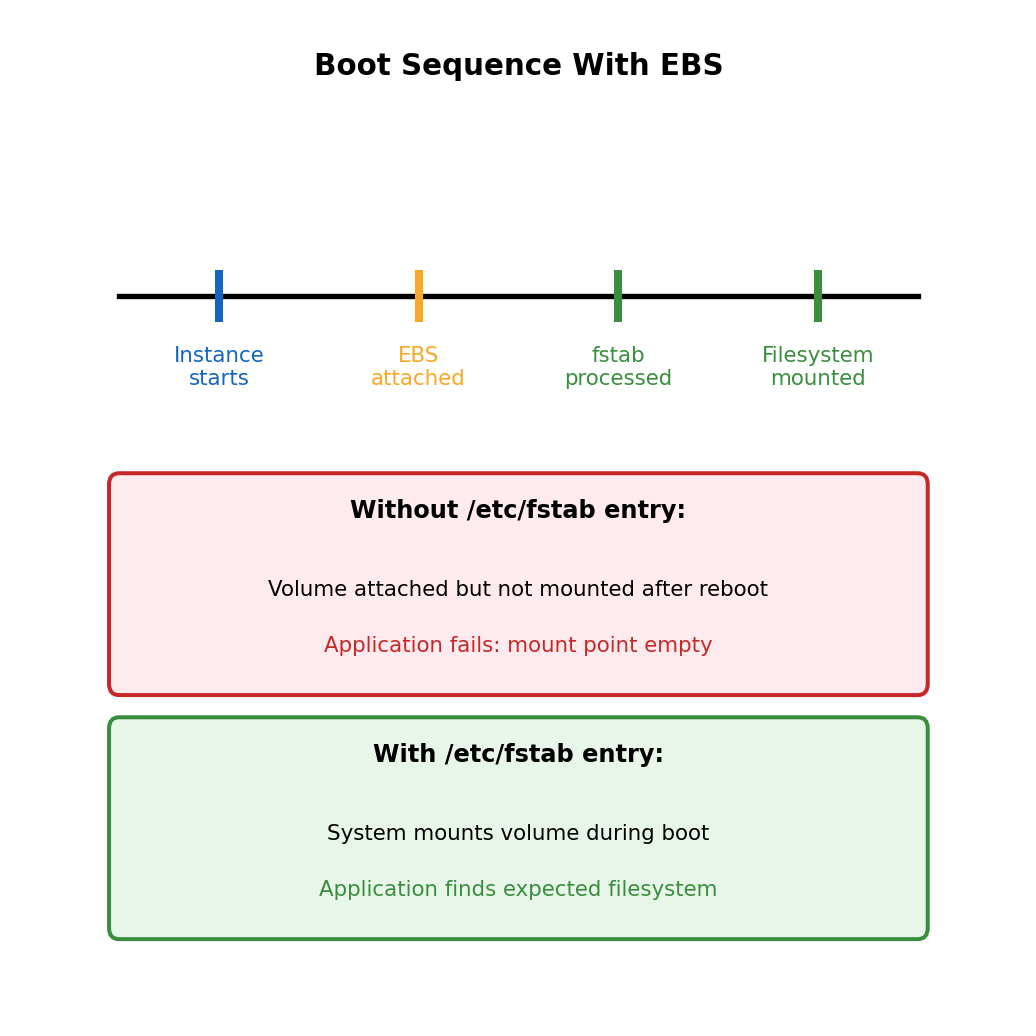

Persistent Mount Configuration

Mount persists only until reboot

The mount command attaches filesystem for current session. After instance reboot, volume is still attached but not mounted.

# After reboot

$ df -h /mnt/data

df: /mnt/data: No such file or directory

# Volume still attached, just not mounted

$ lsblk

NAME SIZE TYPE

nvme1n1 100G disk # Present but not mountedConfigure automatic mount via fstab:

# Get volume UUID (stable identifier)

$ sudo blkid /dev/nvme1n1p1

/dev/nvme1n1p1: UUID="a1b2c3d4-..." TYPE="ext4"

# Add entry to /etc/fstab

$ echo 'UUID=a1b2c3d4-... /mnt/data ext4 defaults,nofail 0 2' | \

sudo tee -a /etc/fstab

# Test fstab entry (mount all entries)

$ sudo mount -a

# Verify

$ df -h /mnt/dataThe nofail option allows instance to boot even if volume attachment fails - prevents boot hang if volume is detached.

Complete EBS setup sequence

# 1. Identify the new volume

lsblk

# 2. Create partition table

sudo parted /dev/nvme1n1 mklabel gpt

sudo parted /dev/nvme1n1 mkpart primary 0% 100%

# 3. Create filesystem

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/nvme1n1p1

# 4. Create mount point

sudo mkdir -p /mnt/data

# 5. Get UUID for fstab

VOLUME_UUID=$(sudo blkid -s UUID -o value /dev/nvme1n1p1)

# 6. Add to fstab for persistent mount

echo "UUID=$VOLUME_UUID /mnt/data ext4 defaults,nofail 0 2" | \

sudo tee -a /etc/fstab

# 7. Mount (using fstab entry)

sudo mount -a

# 8. Verify

df -h /mnt/data

UUID vs device path:

Device names (/dev/nvme1n1) can change between boots depending on attachment order. UUID is stable identifier assigned when filesystem is created.

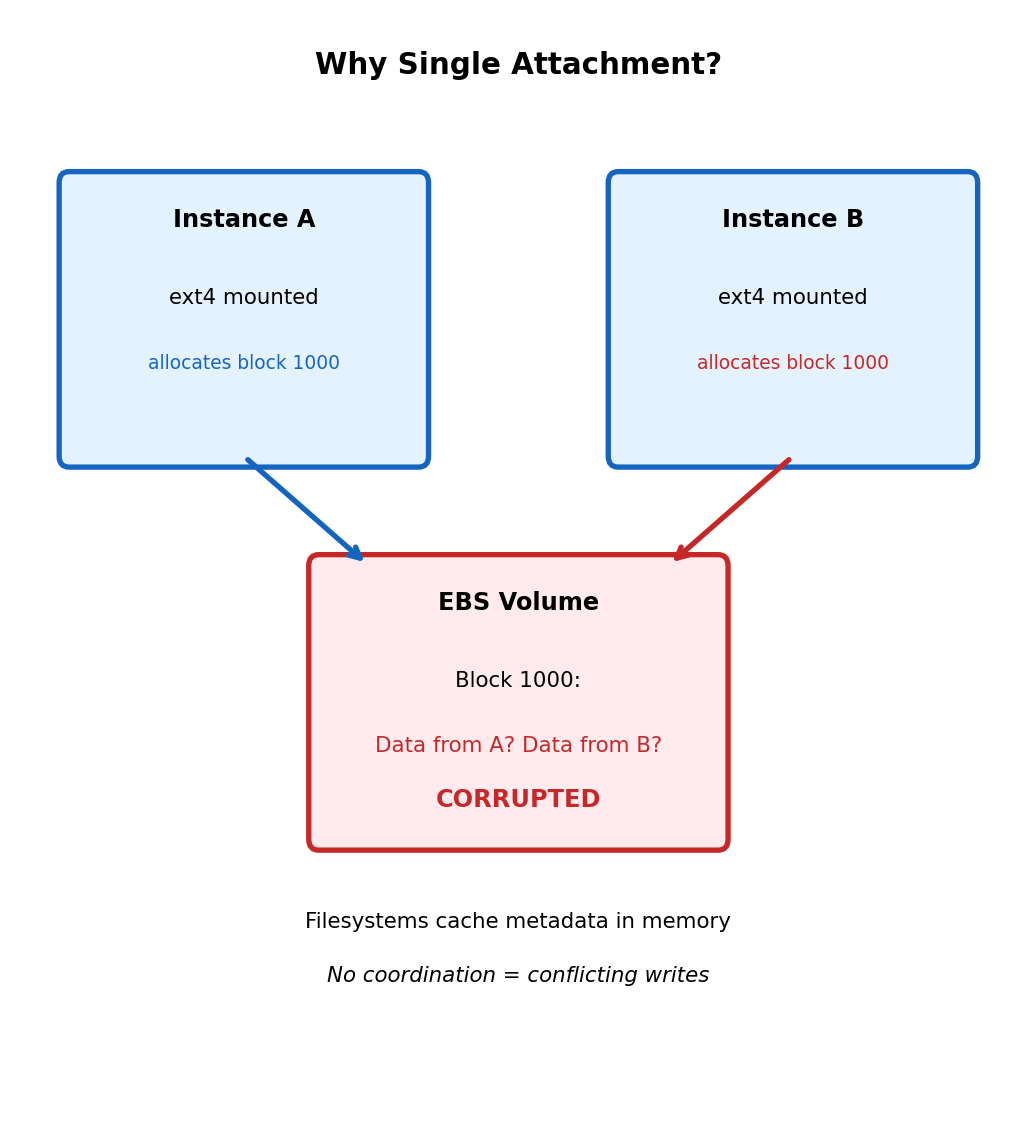

Block Storage Single-Attachment Constraint

Standard EBS volumes attach to one instance at a time

Attempt: Attach vol-0abc123 to Instance B

(currently attached to Instance A)

Error: Volume vol-0abc123 is in 'in-use' state

attached to instance i-0111222333Filesystem design assumes exclusive access

Filesystems like ext4 maintain metadata structures:

- Superblock: filesystem parameters

- Inode tables: file metadata

- Block allocation bitmaps: which blocks are free

These structures are cached in memory and written back to disk. Two instances mounting same volume:

- Instance A allocates block 1000 for new file

- Instance B (unaware) allocates block 1000 for different file

- Both write different data to same location

- Filesystem corruption guaranteed

EBS Multi-Attach (io1/io2 volumes only)

Multi-Attach allows attaching io1 or io2 volume to up to 16 instances. These are provisioned IOPS SSD volumes designed for high-performance workloads.

Requires cluster-aware filesystem (not ext4):

- Shared-disk filesystems: GFS2, OCFS2

- Application-level coordination: Clustered databases

Not general-purpose shared storage - specialized use case requiring explicit coordination.

Standard filesystems cannot coordinate across multiple hosts - they assume single writer.

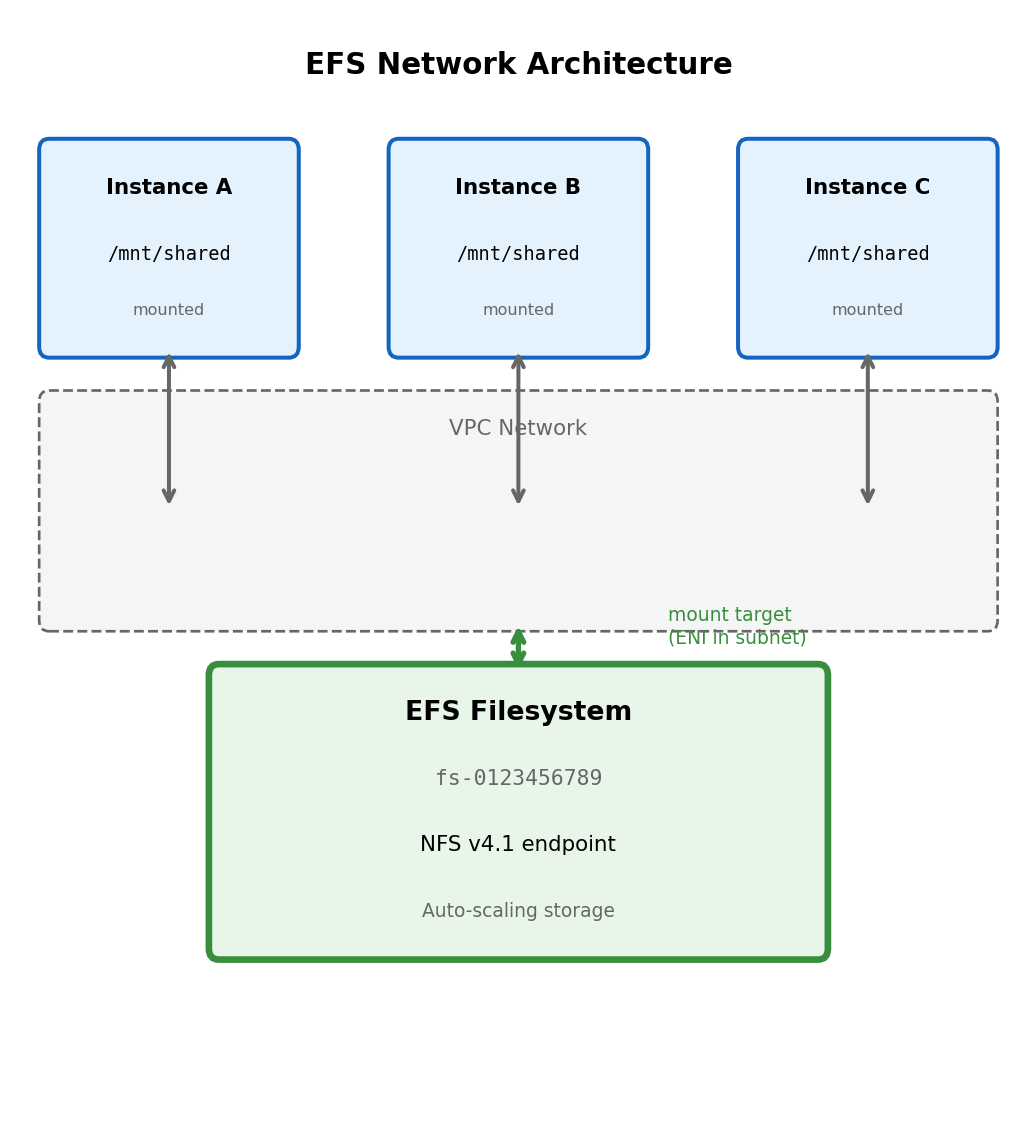

File Storage Shares Filesystem Across Network

Network filesystem architecture

EFS (Elastic File System): Managed NFS service. Multiple instances connect to shared network endpoint (not attached like block storage).

# Mount EFS filesystem (NFS protocol)

$ sudo mount -t nfs4 \

-o nfsvers=4.1,rsize=1048576,wsize=1048576 \

fs-0123456789.efs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com:/ \

/mnt/sharedMount target fs-0123456789.efs.us-east-1.amazonaws.com: DNS name resolving to EFS infrastructure within VPC.

File operations traverse network

# Write on Instance A

with open('/mnt/shared/config.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(config, f)

# Read on Instance B (same filesystem)

with open('/mnt/shared/config.json', 'r') as f:

config = json.load(f) # Sees Instance A's writeEvery read and write is a network operation to EFS service. The filesystem appears local but data travels over network.

NFS protocol handles coordination:

- File locking across clients

- Cache coherency

- Concurrent access semantics

All instances connect to same EFS endpoint. Filesystem state is centralized in EFS service.

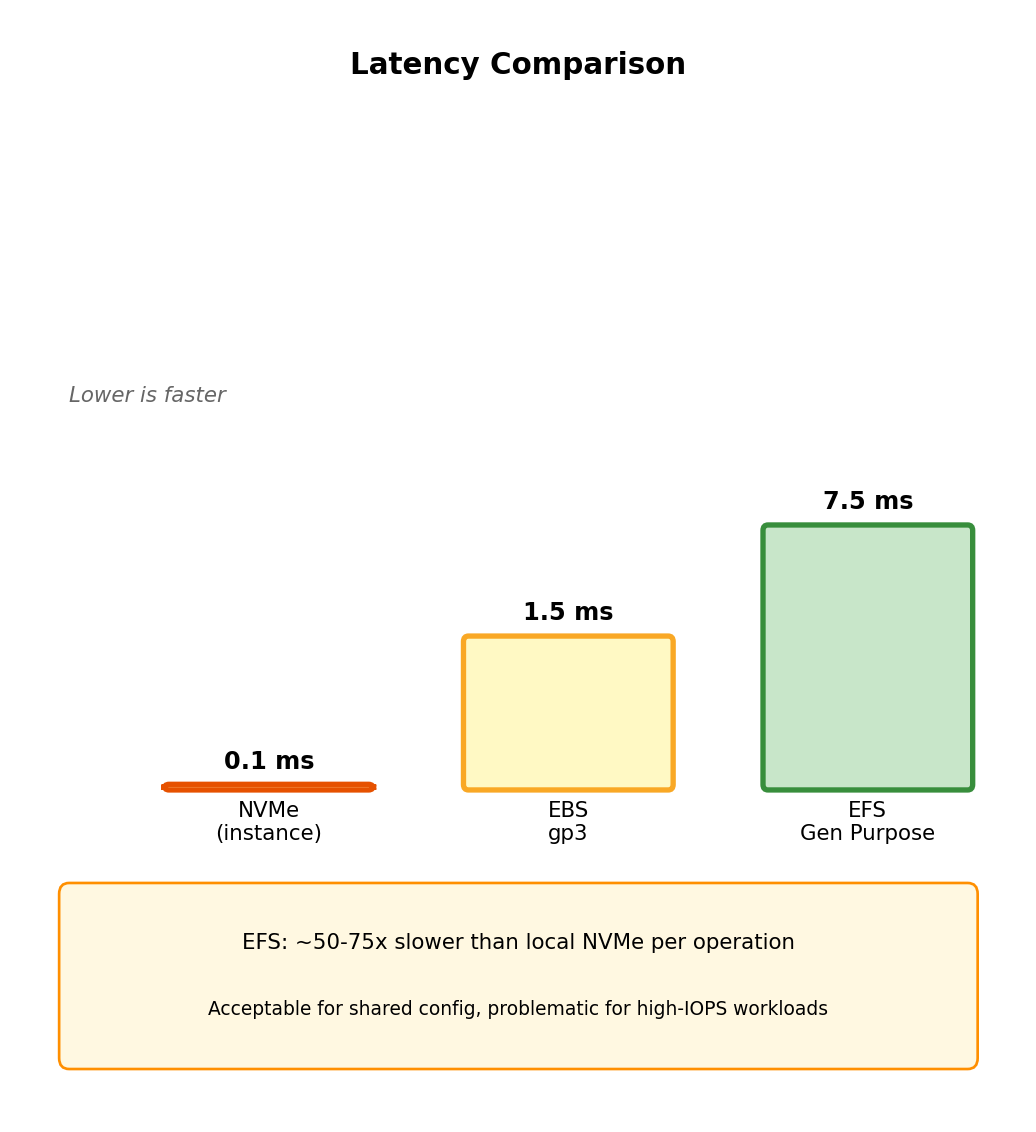

Network Filesystem Performance Characteristics

Latency comparison with local storage

| Storage Type | Read Latency | Write Latency |

|---|---|---|

| Instance store (NVMe) | ~0.1 ms | ~0.1 ms |

| EBS gp3 | ~1-2 ms | ~1-2 ms |

| EFS General Purpose | ~5-10 ms | ~5-10 ms |

| EFS Max I/O | ~10-25 ms | ~10-25 ms |

Every EFS operation crosses network, adds latency overhead compared to locally-attached storage.

Throughput scales with data size

EFS throughput depends on data stored:

- Bursting mode: Baseline throughput + burst credits

- Provisioned mode: Fixed throughput regardless of size

Data stored: 100 GB

Baseline: 5 MB/s (bursting mode)

Burst: Up to 100 MB/s (while credits available)

Data stored: 1 TB

Baseline: 50 MB/sSmall file operations

NFS protocol overhead per operation. Many small files = many round trips.

EFS appropriate for: Shared configuration, content management, home directories.

Not appropriate for: Databases, high-throughput processing, latency-sensitive applications.

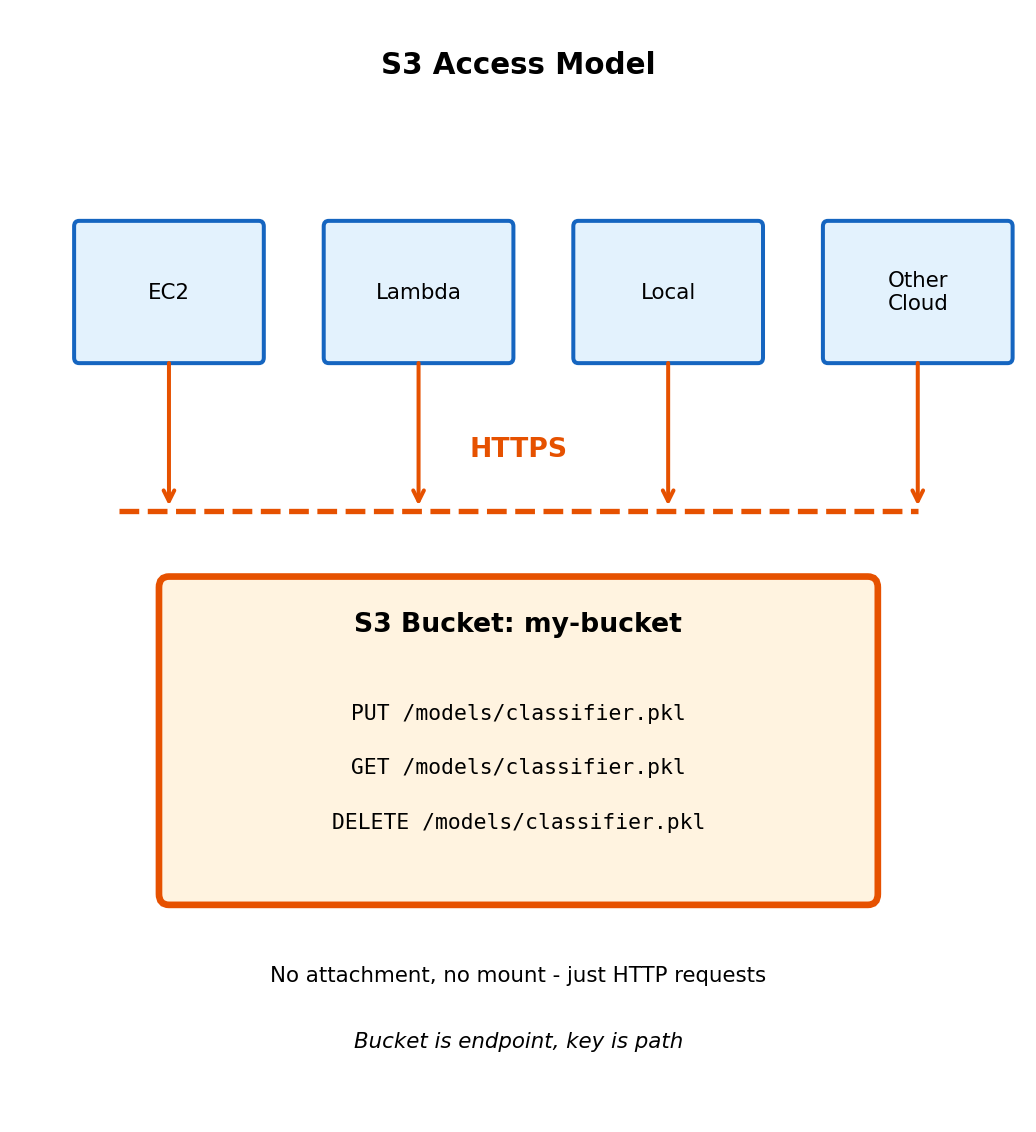

Object Storage Uses HTTP API Instead of Filesystem

S3 operations are HTTP requests

import boto3

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# PUT object (HTTP PUT request)

s3.put_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='models/classifier.pkl',

Body=open('model.pkl', 'rb')

)

# GET object (HTTP GET request)

response = s3.get_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='models/classifier.pkl'

)

data = response['Body'].read()

# DELETE object (HTTP DELETE request)

s3.delete_object(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Key='models/classifier.pkl'

)No filesystem - HTTP semantics:

- Address by bucket + key (like URL path)

- No mount, no file handles

- No directories (keys can contain

/but it’s just a character) - No append (rewrite entire object)

- No rename (copy to new key, delete old)

- No locking (last write wins)

Accessible from anywhere with network:

EC2 instance, Lambda function, laptop, any HTTP client. No attachment, no VPC requirement (with public endpoint).

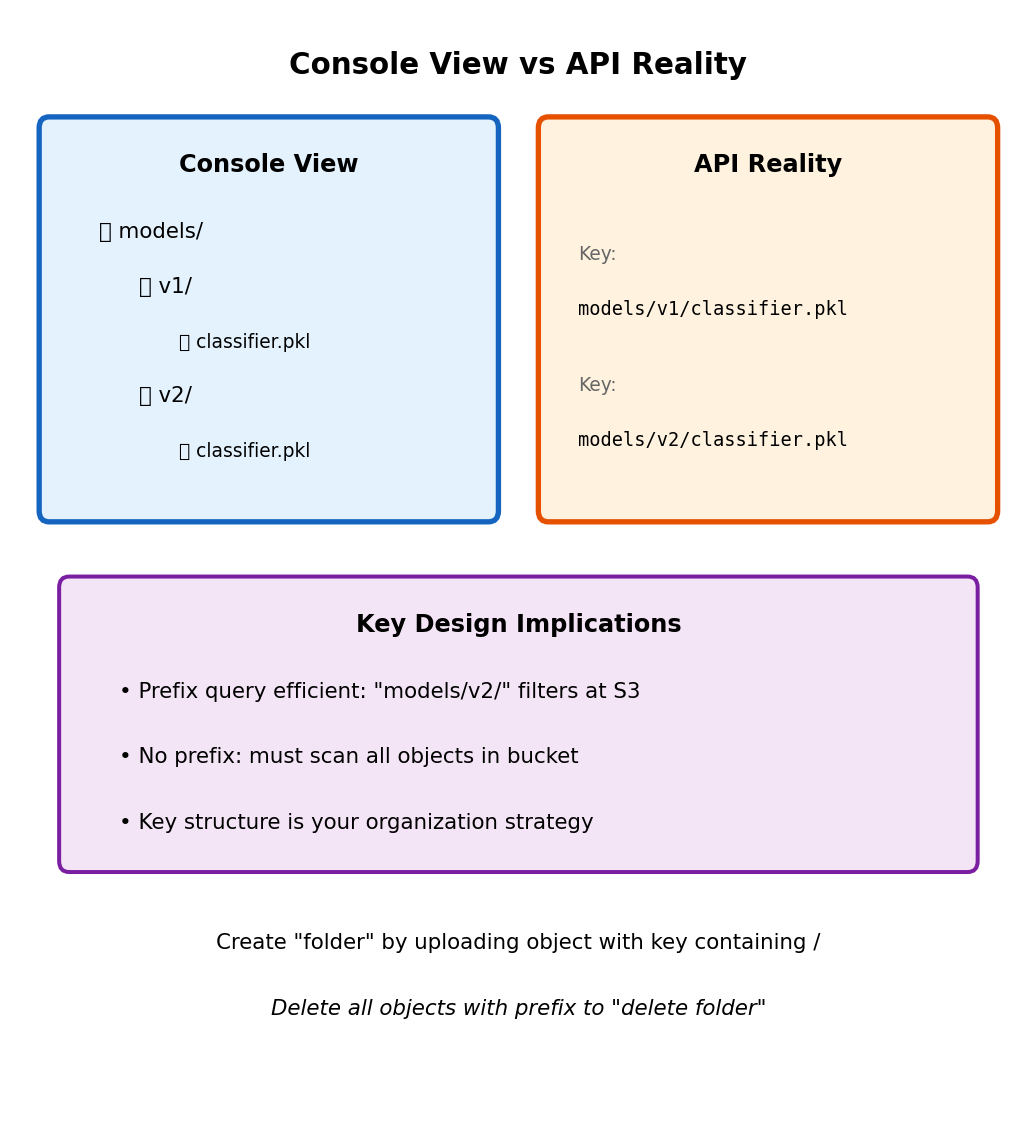

S3 Keys Are Flat Namespace With Path-Like Convention

Console displays folder hierarchy - API stores flat keys

AWS Console shows:

my-bucket/

├── models/

│ ├── v1/

│ │ └── classifier.pkl

│ └── v2/

│ └── classifier.pkl

└── uploads/

└── user123/

└── document.pdfActual S3 contents (three objects, flat):

No “models” folder exists. The / characters are part of the key string, not directory separators.

Listing with prefix filter:

# "List directory contents" = list objects with prefix

response = s3.list_objects_v2(

Bucket='my-bucket',

Prefix='models/'

)

for obj in response['Contents']:

print(obj['Key'])

# models/v1/classifier.pkl

# models/v2/classifier.pklDelimiter simulates directory listing:

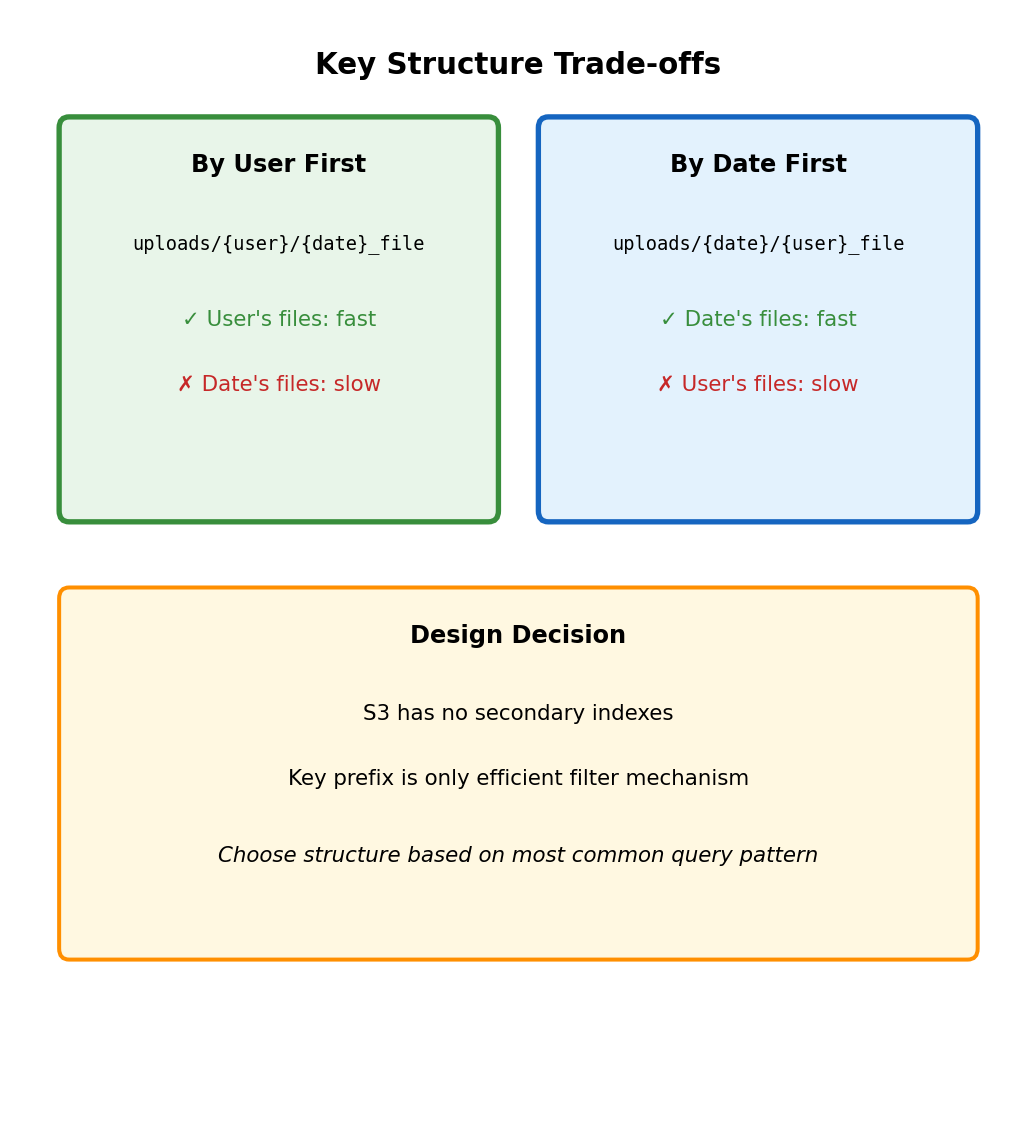

S3 Key Design Affects Query Efficiency

Key prefix determines what queries are efficient

# Key structure: {type}/{user_id}/{timestamp}_{filename}

# Example: uploads/user123/2025-01-15_document.pdf

# Efficient: All uploads for specific user

s3.list_objects_v2(

Bucket='app-data',

Prefix='uploads/user123/'

)

# S3 filters at storage layer, returns only matching objects

# Inefficient: All uploads from specific date

# No prefix helps - must scan all objects, filter client-side

response = s3.list_objects_v2(Bucket='app-data', Prefix='uploads/')

for obj in response['Contents']:

if '2025-01-15' in obj['Key']:

# Found oneAlternative key structure for date queries:

# Key structure: {type}/{date}/{user_id}_{filename}

# Example: uploads/2025-01-15/user123_document.pdf

# Now efficient: All uploads from specific date

s3.list_objects_v2(

Bucket='app-data',

Prefix='uploads/2025-01-15/'

)

# Now inefficient: All uploads for specific user

# Must scan all datesChoose key structure based on primary access pattern. Cannot efficiently query by both user and date with single key structure.

Secondary access patterns may require maintaining separate key hierarchies (duplication) or external index (database).

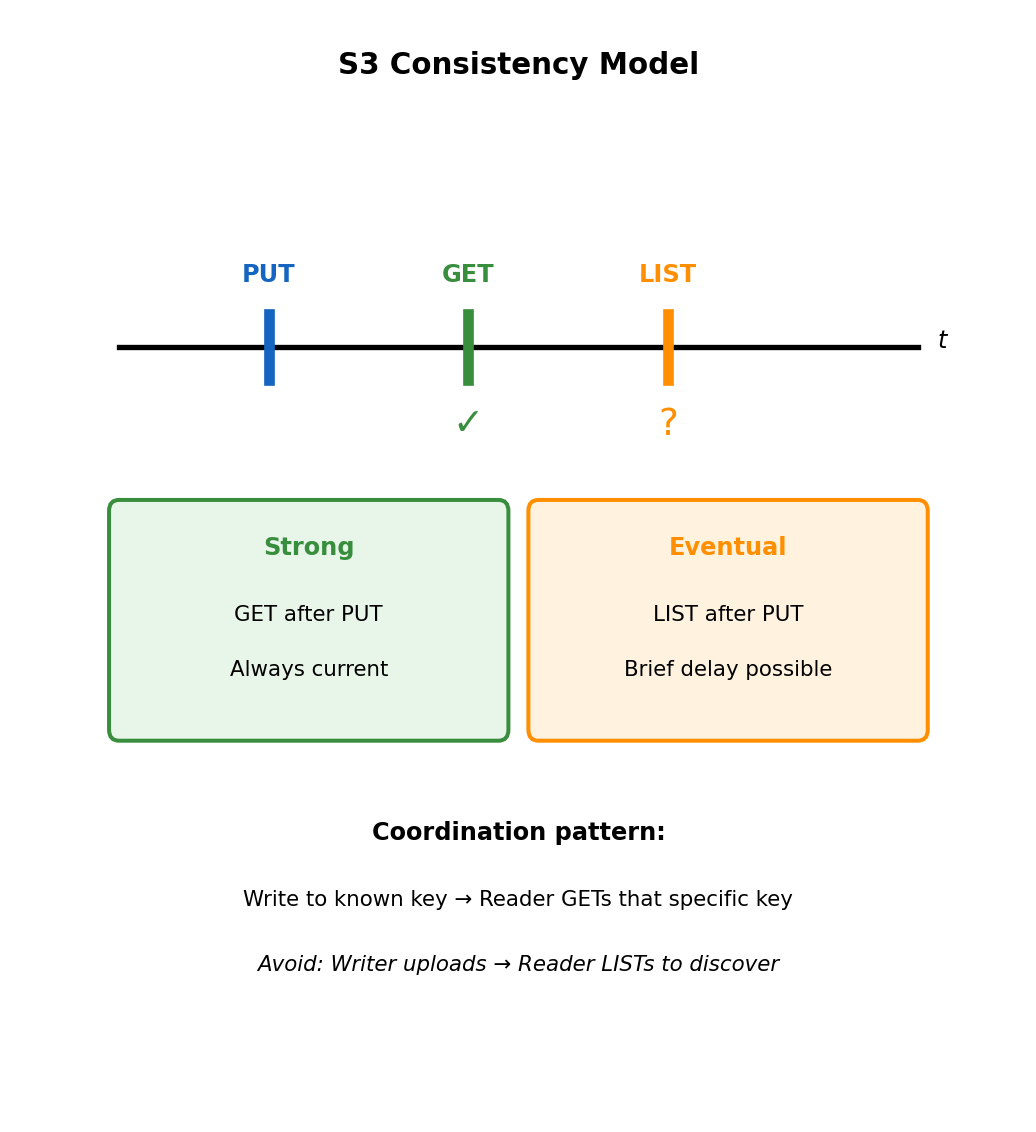

S3 Provides Strong Read-After-Write Consistency

Write then read returns current data

# Process A: Write object

s3.put_object(

Bucket='data',

Key='results/job-123.json',

Body=json.dumps({'status': 'complete', 'score': 0.94})

)

# Process B: Read immediately after

response = s3.get_object(

Bucket='data',

Key='results/job-123.json'

)

result = json.loads(response['Body'].read())

# Guaranteed to see Process A's writeConsistency guarantees:

| Operation Sequence | Guarantee |

|---|---|

| PUT → GET (same key) | Strong: sees new data |

| DELETE → GET | Strong: returns 404 |

| PUT → LIST | Eventual: may not appear immediately |

| Overwrite → GET | Strong: sees new version |

LIST operations may lag briefly

# Upload new object

s3.put_object(Bucket='data', Key='new-file.json', Body='{}')

# Immediate LIST might not include it

response = s3.list_objects_v2(Bucket='data', Prefix='')

# new-file.json may not appear in Contents yet

# But direct GET works immediately

s3.get_object(Bucket='data', Key='new-file.json') # SucceedsFor coordination between processes, use direct GET with known key rather than LIST to discover objects.

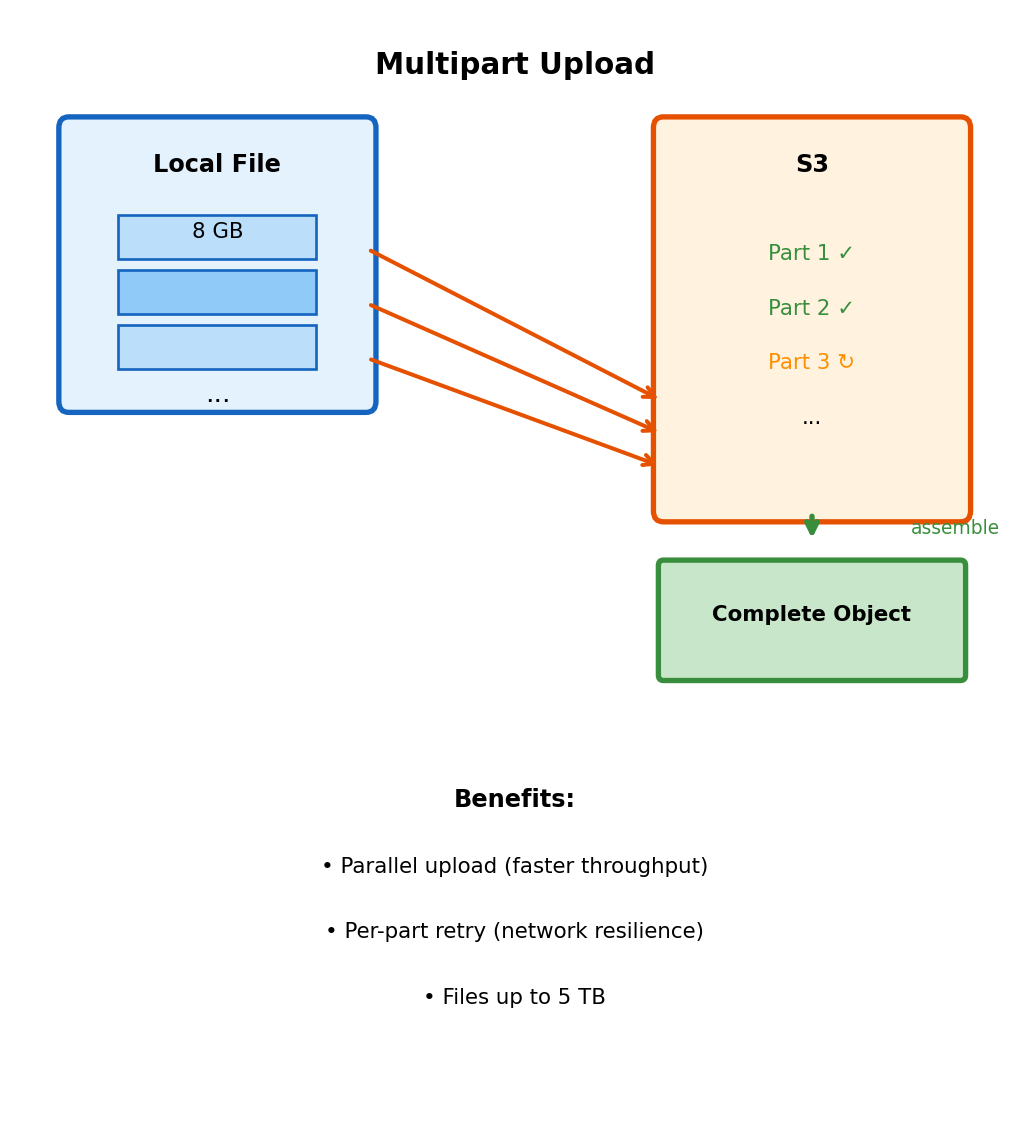

Uploading Large Files: Multipart Upload

Single PUT has limits and reliability issues

- Maximum single PUT: 5 GB

- Large uploads over unreliable networks: Failure requires restart from beginning

- No parallelization: Single stream to S3

Multipart upload splits file into parts

# boto3 handles multipart automatically for large files

s3.upload_file(

Filename='large_model.tar.gz', # 8 GB file

Bucket='ml-artifacts',

Key='models/large_model.tar.gz'

)

# Automatically uses multipart for files > 8 MB (configurable)Multipart mechanics:

- Initiate multipart upload → receive UploadId

- Upload parts (5 MB - 5 GB each) with part numbers

- Parts can upload in parallel, retry individually

- Complete upload → S3 assembles parts into single object

# Explicit multipart control

from boto3.s3.transfer import TransferConfig

config = TransferConfig(

multipart_threshold=100 * 1024 * 1024, # Use multipart > 100 MB

multipart_chunksize=50 * 1024 * 1024, # 50 MB parts

max_concurrency=10 # 10 parallel uploads

)

s3.upload_file('huge_file.bin', 'bucket', 'key', Config=config)Failed part retries only that part, not entire file. Parallel uploads improve throughput on high-bandwidth connections.

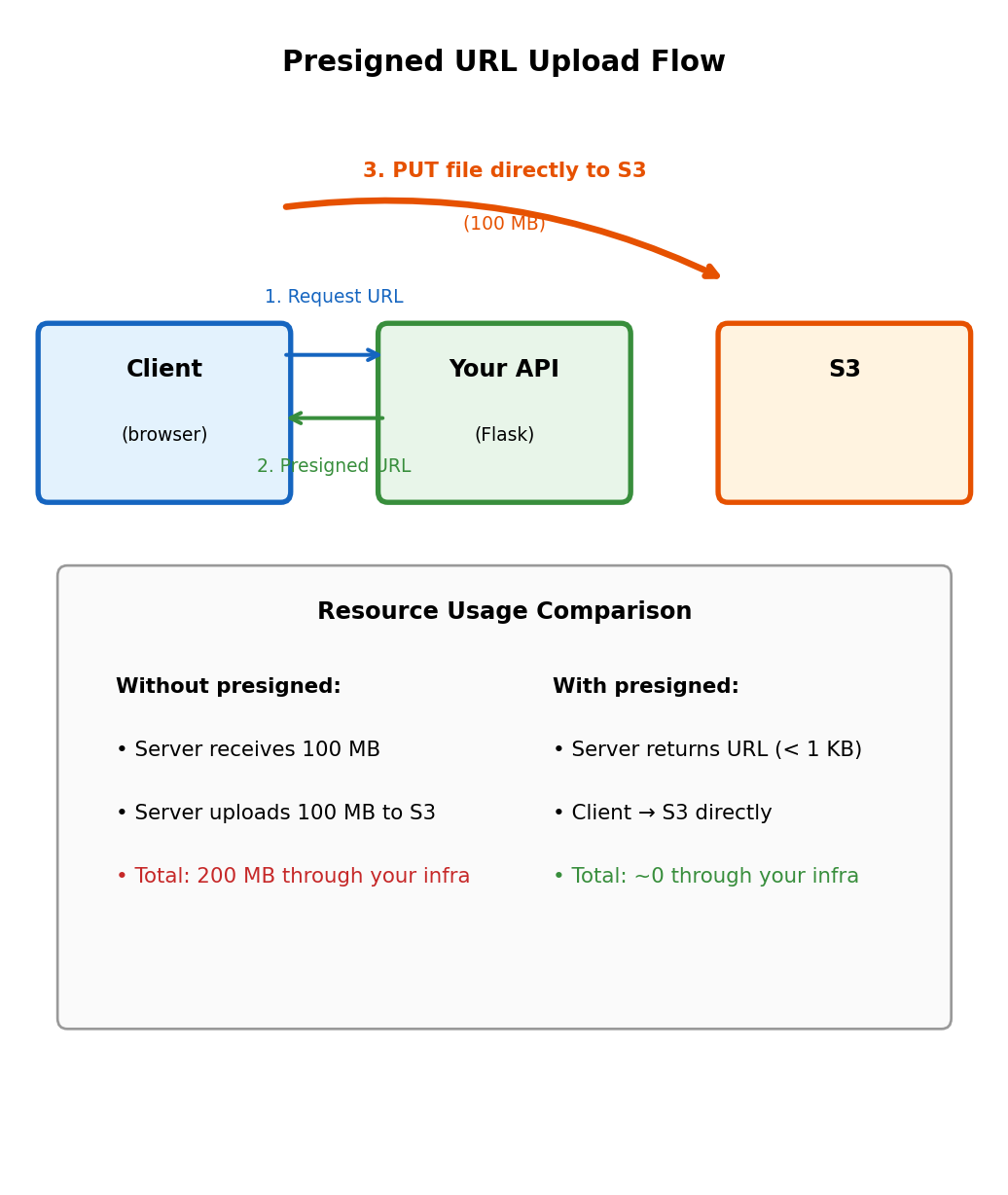

Presigned URLs Enable Direct Client-to-S3 Transfer

Without presigned URLs: All data flows through your server

# Client uploads to your API

@app.route('/upload', methods=['POST'])

def upload():

file = request.files['document']

# File bytes received by your server

# Then uploaded to S3

s3.upload_fileobj(file, 'bucket', f'uploads/{file.filename}')

return {'status': 'uploaded'}500 MB file: Consumes your server’s bandwidth, memory, CPU, and time.

With presigned URLs: Client uploads directly to S3

# Your API generates presigned URL (< 1 ms)

@app.route('/get-upload-url', methods=['POST'])

def get_upload_url():

key = f"uploads/{uuid.uuid4()}/{request.json['filename']}"

url = s3.generate_presigned_url(

'put_object',

Params={'Bucket': 'uploads-bucket', 'Key': key},

ExpiresIn=3600 # URL valid for 1 hour

)

return {'upload_url': url, 'key': key}

# Client uploads directly to S3 using presigned URL

# Your server never handles the file bytesPresigned URL contains embedded authorization:

https://uploads-bucket.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/abc123/doc.pdf

?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256

&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA.../us-east-1/s3/aws4_request

&X-Amz-Date=20250115T100000Z

&X-Amz-Expires=3600

&X-Amz-Signature=a1b2c3d4...Signature validates: Bucket, key, expiration time. Cannot be modified - S3 verifies signature.

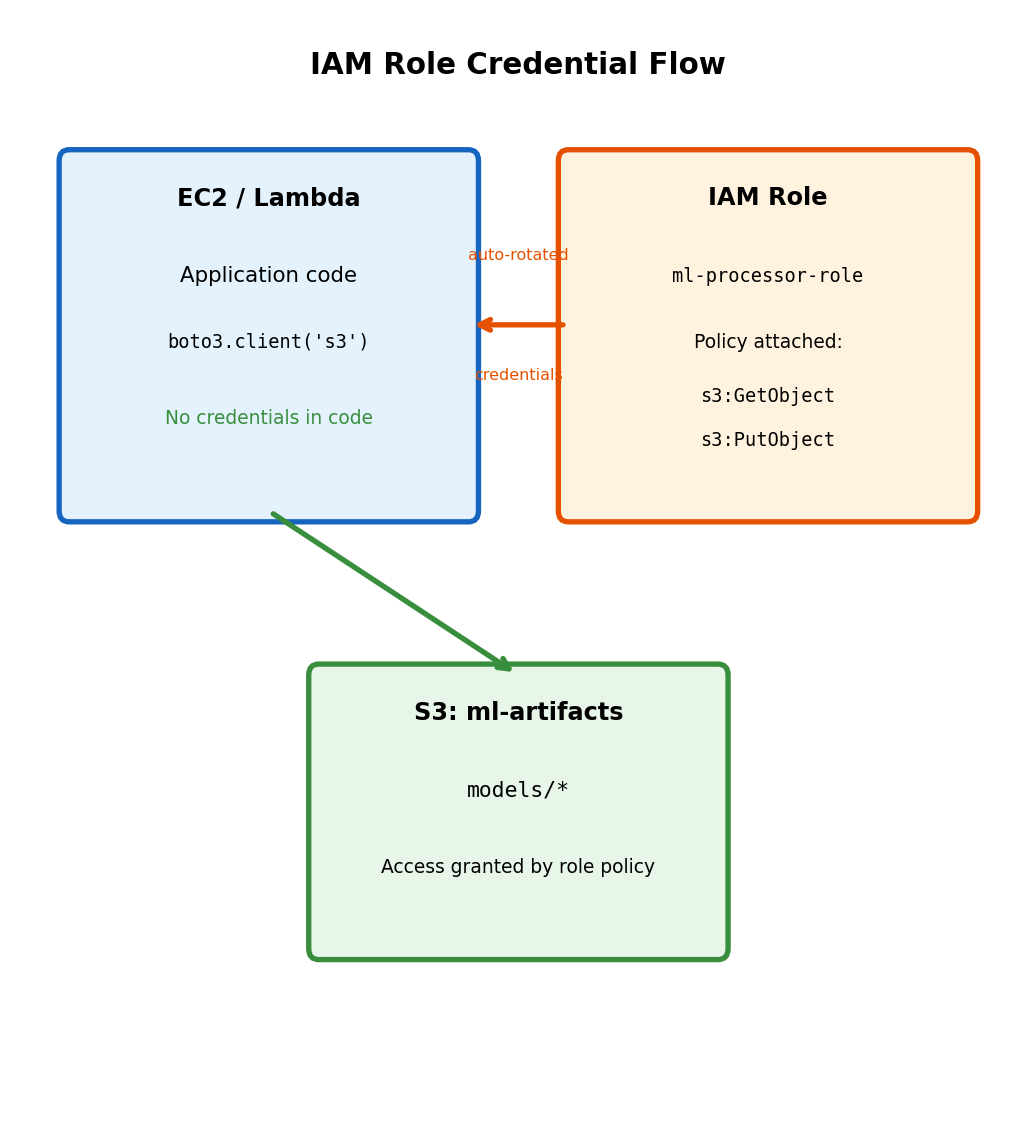

IAM Roles Provide Automatic Credential Management

Credentials embedded in code or environment: Security risk

# Dangerous: Credentials in code

s3 = boto3.client('s3',

aws_access_key_id='AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE',

aws_secret_access_key='wJalrXUtnFEMI/K7MDENG/bPxRfiCYEXAMPLEKEY'

)

# Credentials visible in: git history, logs, error traces, process listingIAM role attached to compute resource

# EC2 instance or Lambda with IAM role

import boto3

s3 = boto3.client('s3') # No credentials specified

s3.upload_file('model.pkl', 'bucket', 'key') # Worksboto3 automatically retrieves credentials from instance metadata service. Credentials rotate automatically (typically hourly). No secrets in code, environment variables, or configuration files.

IAM policy controls access:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": ["s3:GetObject", "s3:PutObject"],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::ml-artifacts/models/*"

}]

}This policy: Allows read/write to models/ prefix in ml-artifacts bucket. Denies access to other prefixes, other buckets, delete operations.

Attach policy to IAM role, attach role to EC2 instance or Lambda function.

No secrets to manage, rotate, or leak. AWS handles credential lifecycle.

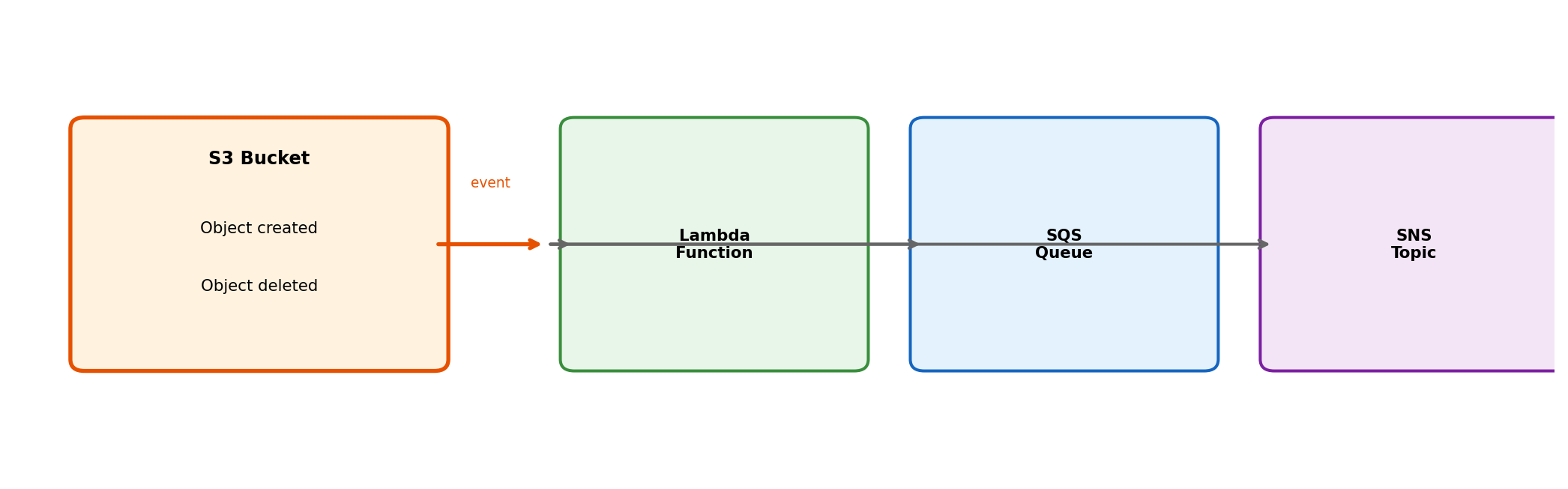

S3 Event Notifications Signal Object Changes

S3 can emit events when objects are created, deleted, or restored

Event configuration on bucket:

- Event types:

s3:ObjectCreated:*,s3:ObjectRemoved:*,s3:ObjectRestore:* - Filter by prefix: Only events for keys starting with

uploads/ - Filter by suffix: Only events for keys ending with

.jpg

Event payload includes:

- Bucket name

- Object key

- Object size

- Event type and timestamp

This enables event-driven architectures: Object uploaded → trigger processing automatically. Integration with Lambda, SQS, and SNS covered in subsequent sections.

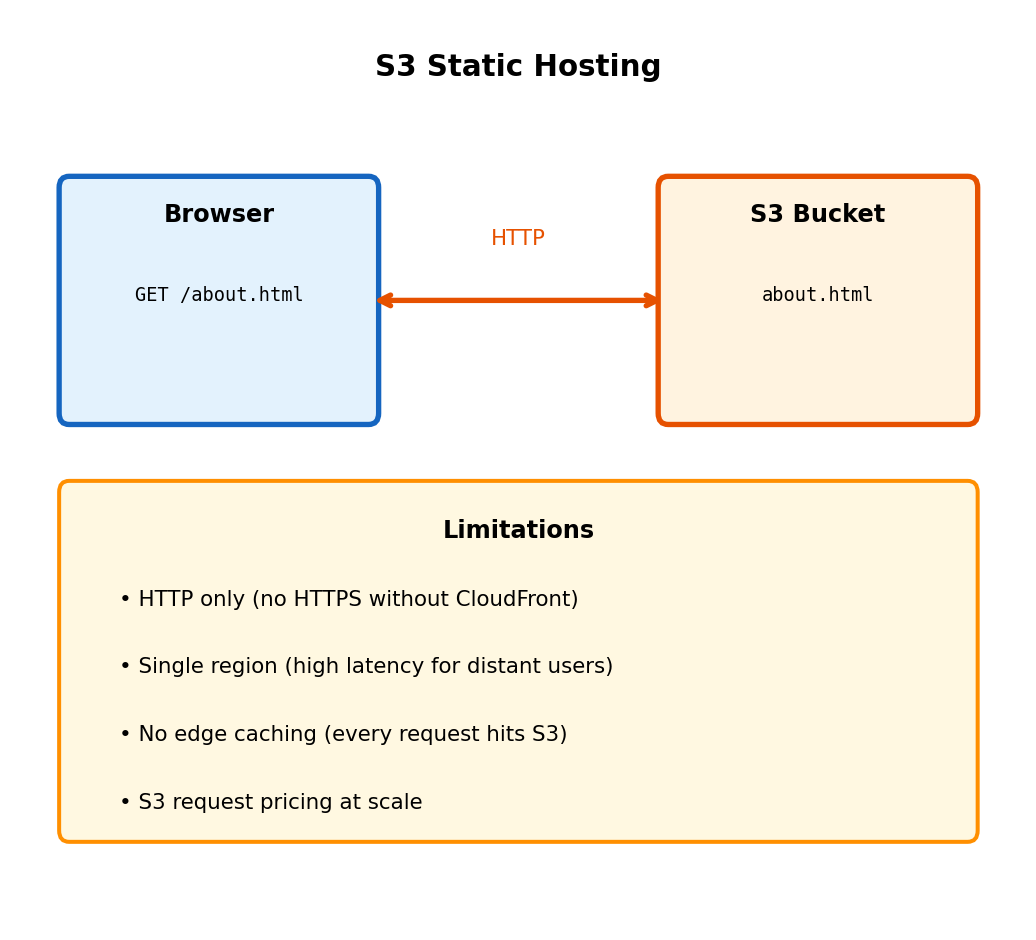

S3 Static Website Hosting

Serve static files directly from S3 bucket

Configure bucket for website hosting:

Bucket contents:

Access via website endpoint:

http://my-site-bucket.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/Browser requests index.html → S3 returns file contents.

Requires public access policy:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": "s3:GetObject",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::my-site-bucket/*"

}]

}Anyone can read objects. Appropriate for public static content.

Direct S3 hosting: Development, internal tools. Production typically adds CloudFront for HTTPS, caching, custom domains - covered in integration section.

Choosing Storage Model

Block when application requires filesystem: Database storage, applications using file paths and standard I/O.

File when multiple instances need shared filesystem: Shared configuration, content management, legacy applications.

Object when HTTP API is acceptable: ML models, user uploads, static assets, backups, any blob storage.

Selection follows from access requirements, not preference.

Serverless Compute

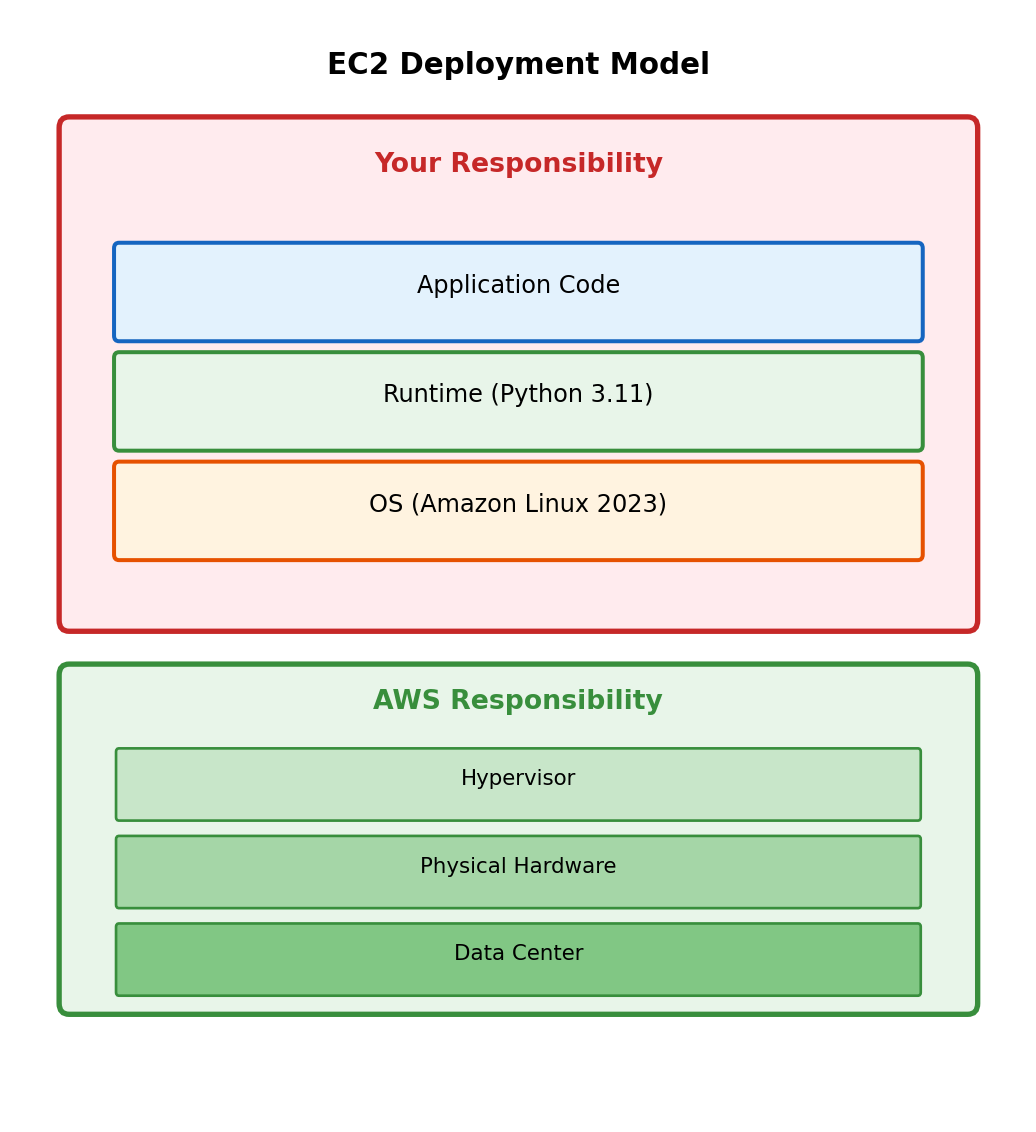

Server Management in Traditional Deployment

EC2 deployment requires operational decisions:

- Instance type selection (compute/memory balance)

- Operating system installation and updates

- Application runtime setup (Python, Node.js, etc.)

- Security patches and maintenance windows

- Scaling policy configuration

- Health monitoring and alerting

- Load balancer configuration

Your application runs on infrastructure you provision and maintain. The application is always resident - process starts at boot, listens for requests, handles them as they arrive.

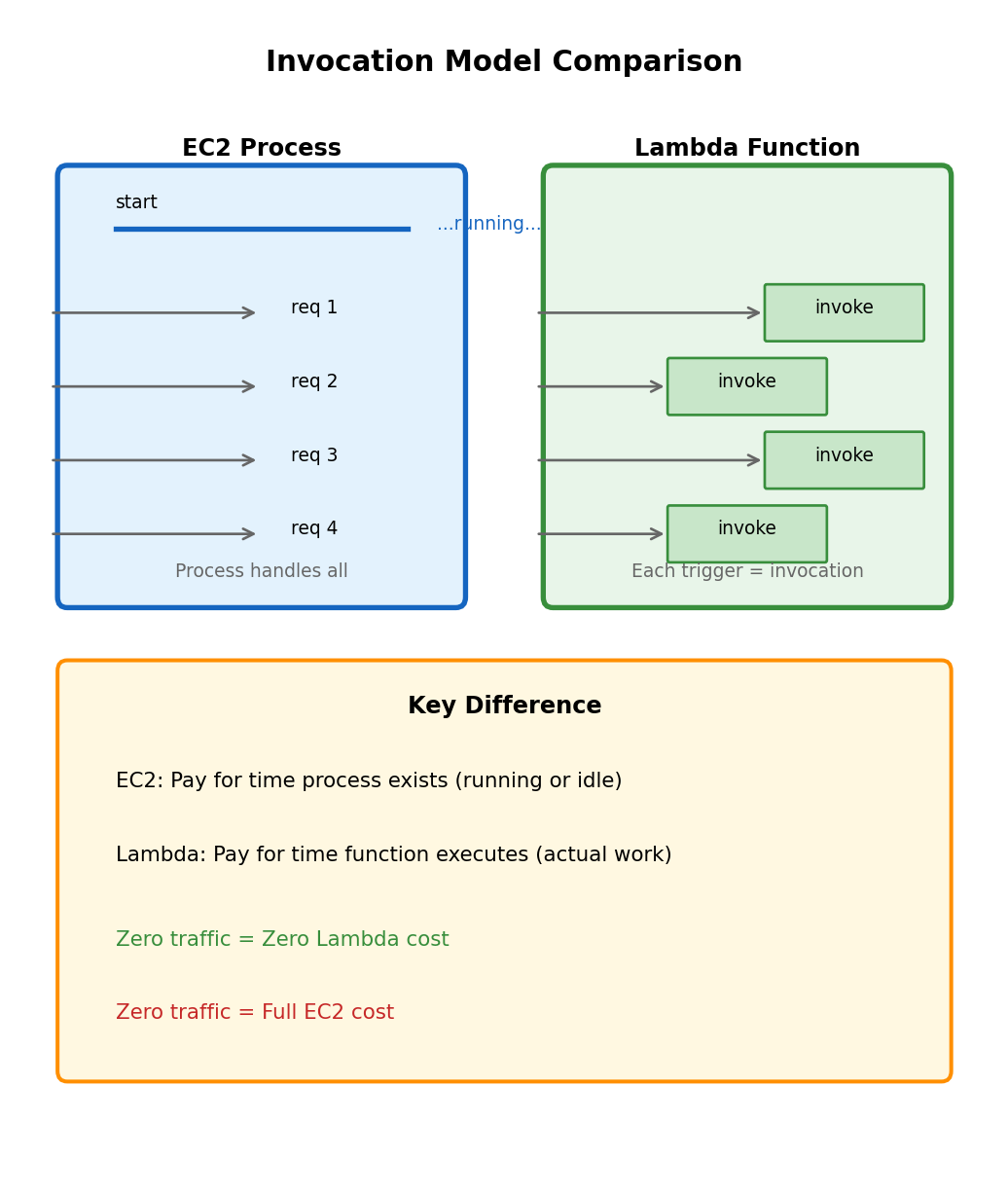

Cost model: Pay for instance hours

Instance runs continuously whether handling 1000 requests/second or 0 requests.

# Check if your Flask app is running

$ ps aux | grep gunicorn

user 12345 0.1 1.2 gunicorn: master [app:app]

user 12346 0.0 0.8 gunicorn: worker [app:app]

user 12347 0.0 0.8 gunicorn: worker [app:app]

# It's running. Waiting for requests. Costing money.The t3.medium running your API costs ~$30/month whether it handles traffic or sits idle.

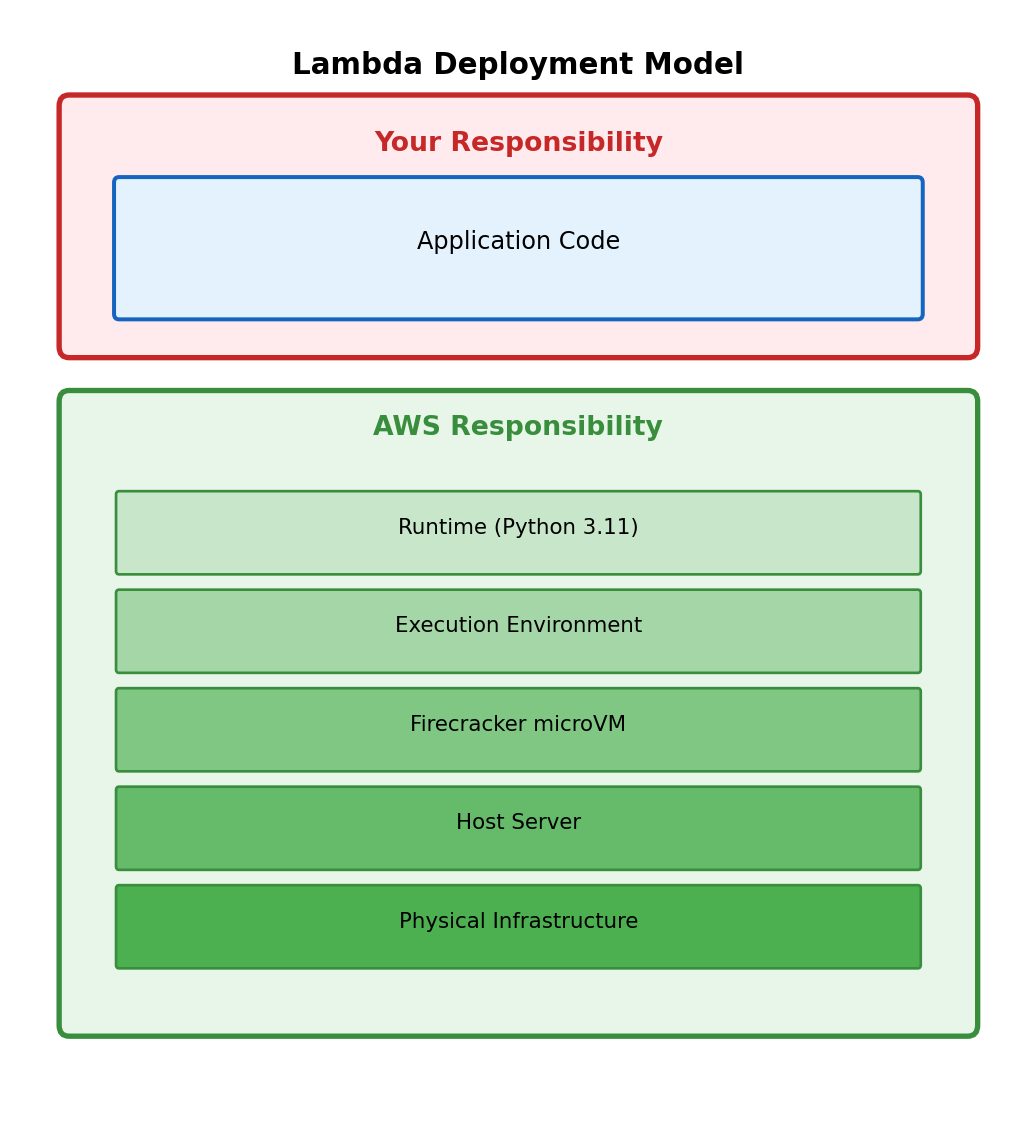

Shifting the Responsibility Boundary

What if AWS managed more of the stack?

Instead of provisioning an EC2 instance where your code runs continuously, you provide only the code. AWS handles:

- Execution environment provisioning

- Runtime installation and patching

- Scaling (including to zero)

- Server allocation and management

The trade-off:

You give up control over the execution environment in exchange for not managing it. No SSH access, no persistent processes, no direct filesystem.

Lambda function: Code as the deployment unit

# handler.py - This IS your entire deployment

def handler(event, context):

"""AWS invokes this function when triggered"""

name = event.get('name', 'World')

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'body': f'Hello, {name}!'

}No Flask, no gunicorn, no server configuration. You deploy this function. AWS runs it when something triggers it.

“Serverless” doesn’t mean no servers - it means servers aren’t your concern.

AWS manages runtime, patching, scaling, and infrastructure. You manage code.

Function Invocation vs. Process Lifecycle

EC2: Long-running process

# Flask app - process starts once, handles many requests

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/greet')

def greet():

return f'Hello, {request.args.get("name", "World")}!'

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=5000)

# Process runs until terminated

# Maintains state between requests

# Keeps connections openThe process initializes once. Each request uses the already-running process.

Lambda: Function invoked per trigger

# Lambda handler - invoked fresh for each trigger

def handler(event, context):

# No persistent process

# No listening socket

# Function runs, returns, done

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'body': f'Hello, {event.get("name", "World")}!'

}Your function is invoked when something triggers it. There’s no “main” loop, no server listening. Lambda is not running your code right now - it will run your code when triggered.

The event parameter contains trigger data:

- HTTP request details (if triggered by API Gateway)

- S3 object information (if triggered by S3 event)

- Message body (if triggered by SQS message)

- Custom JSON (if triggered directly)

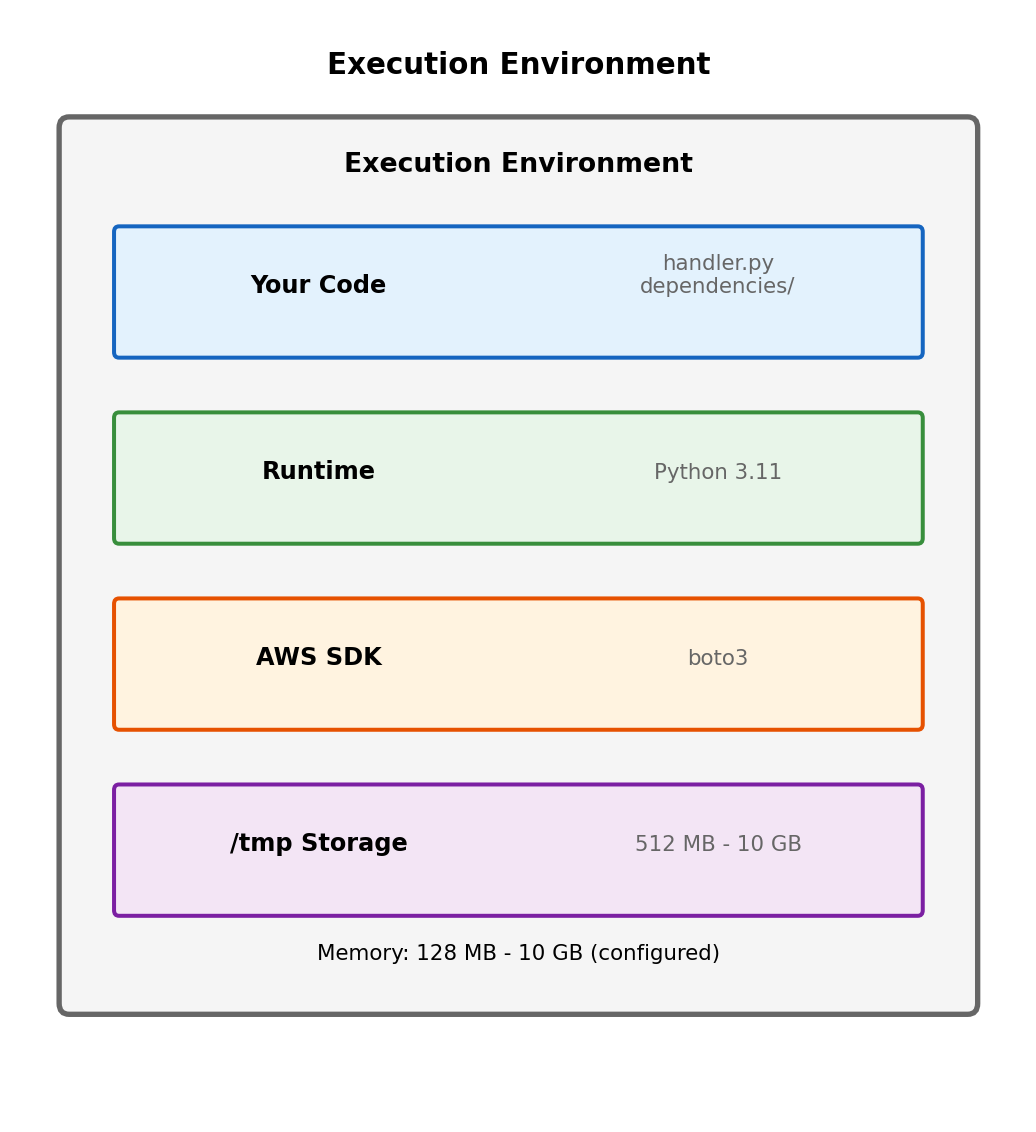

What is an Execution Environment?

Lambda functions don’t run directly on bare hardware. AWS creates an execution environment - an isolated container-like sandbox for your code.

Execution environment provides:

- Runtime (Python 3.11, Node.js 20, etc.)

- Your deployed code (handler + dependencies)

- Allocated memory (128 MB - 10 GB, you configure)

- Temporary filesystem (

/tmp, 512 MB - 10 GB) - Environment variables you configure

- AWS SDK for your runtime

Execution environment isolation:

- Each environment isolated from others

- Cannot see or affect other functions

- Cannot see concurrent invocations of same function

# Your handler runs inside the execution environment

def handler(event, context):

# context provides environment information

print(f"Request ID: {context.aws_request_id}")

print(f"Memory limit: {context.memory_limit_in_mb} MB")

print(f"Time remaining: {context.get_remaining_time_in_millis()} ms")

# Do work

return {'statusCode': 200, 'body': 'Done'}context object provides invocation and environment information.

The execution environment is the sandbox where your function runs. You configure its resources; AWS manages its lifecycle.

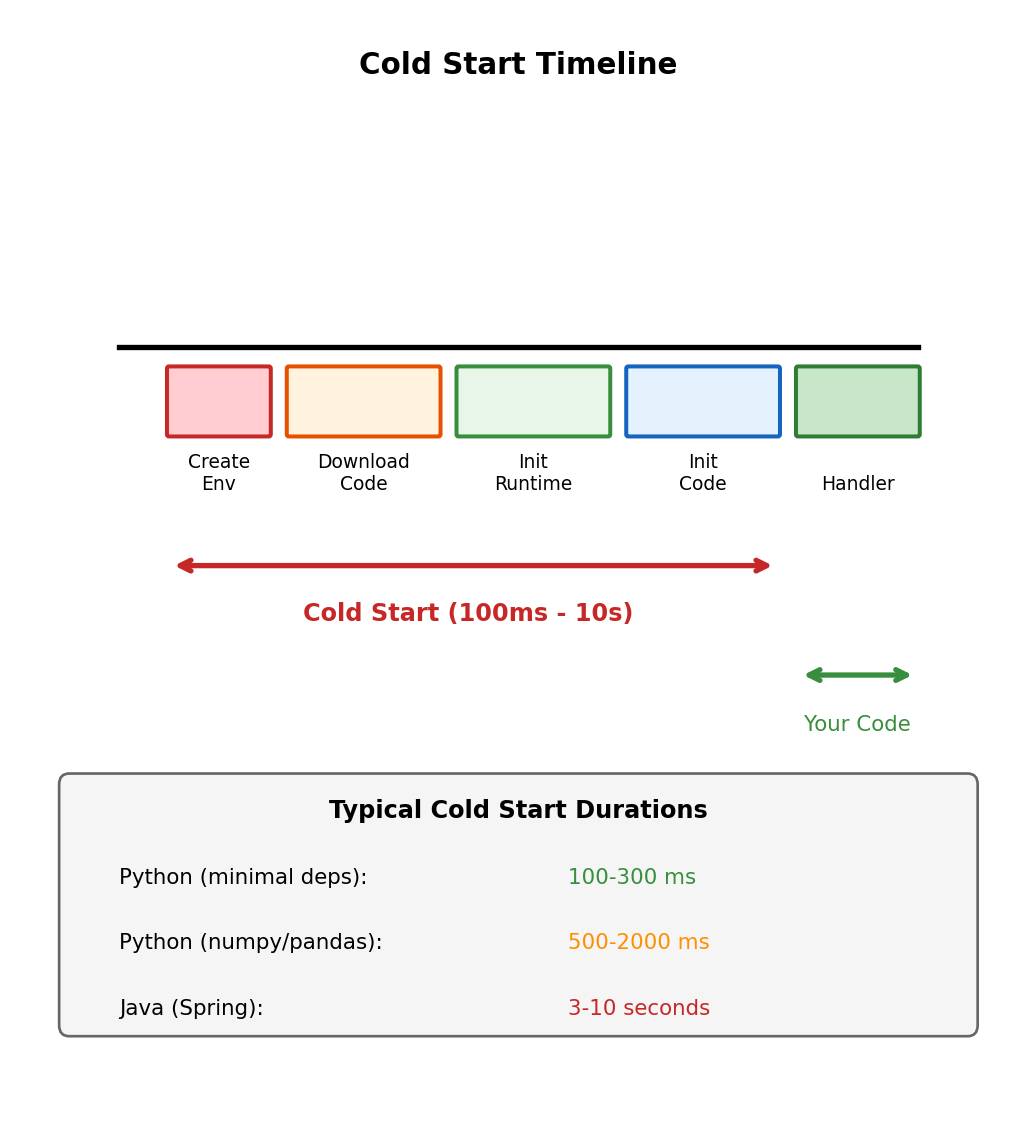

Cold Start: Creating a New Execution Environment

First invocation creates the environment

No suitable execution environment exists → Lambda must create one. This is a cold start.

Cold start phases:

- Environment creation - AWS allocates resources, creates the sandbox

- Code download - Your deployment package downloaded from S3

- Runtime initialization - Python interpreter starts, loads modules

- Handler initialization - Code outside handler function runs

# handler.py

import json

import boto3

import heavy_ml_library # Imported during cold start

# This runs ONCE during cold start, not per invocation

s3_client = boto3.client('s3')

model = heavy_ml_library.load_model('model.pkl')

def handler(event, context):

# This runs on EVERY invocation

result = model.predict(event['data'])

return {'statusCode': 200, 'body': json.dumps(result)}Imports and module-level code execute during initialization. handler function executes on each invocation.

Cold start duration depends on:

- Deployment package size

- Number and size of dependencies

- Initialization code complexity

- Runtime choice (Python, Java, Node.js differ)

- Memory allocation (more memory = faster CPU = faster init)

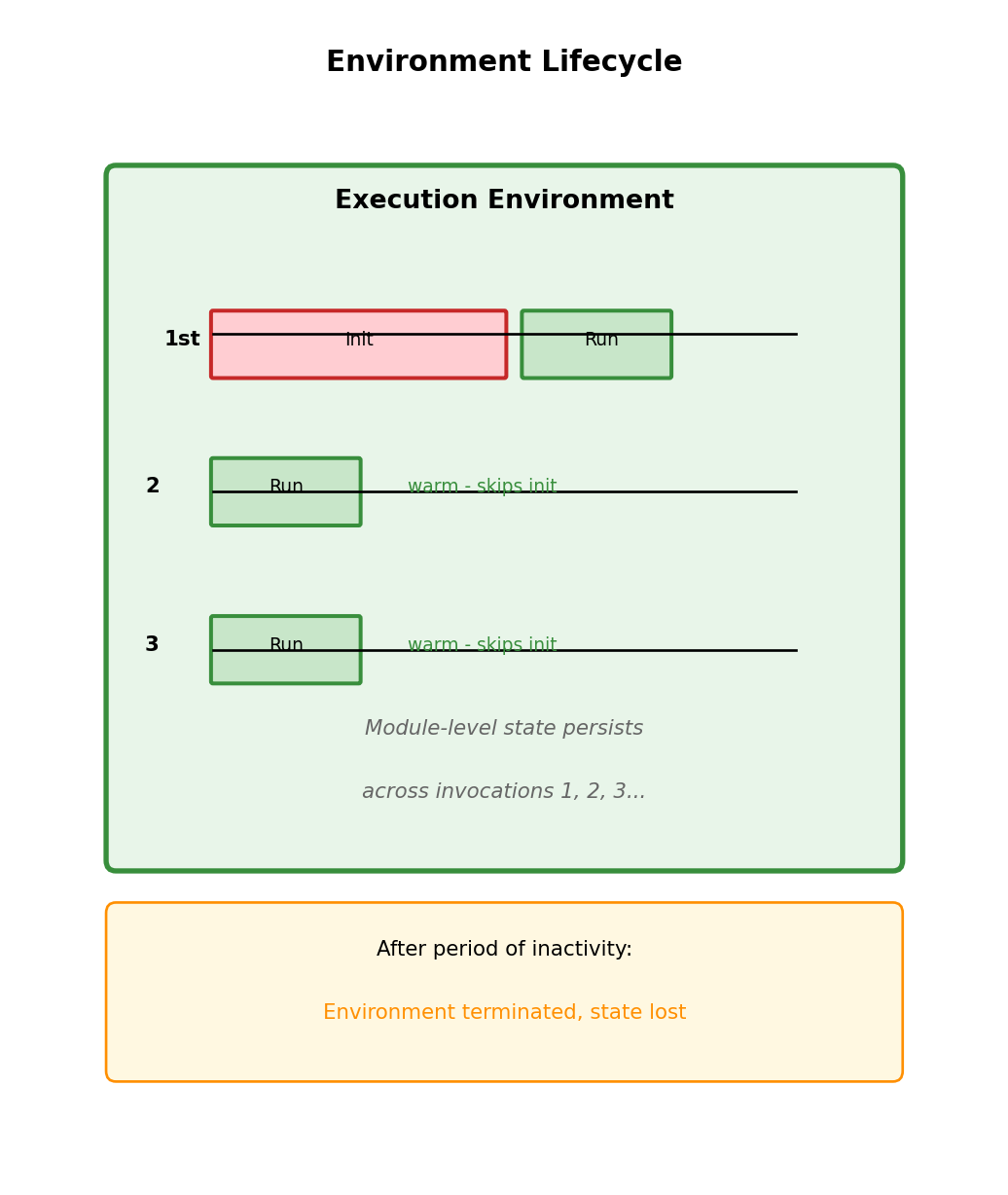

Warm Invocation: Reusing Execution Environments

AWS keeps execution environments alive

After function completes, environment isn’t immediately destroyed. Kept available for subsequent invocations → can be reused.

Warm invocation skips initialization:

Cold: [Create Env][Download][Init Runtime][Init Code][Handler]

Warm: [Handler]Warm invocations go directly to handler - no environment creation, downloads, or initialization.

Environment reuse implications:

# Module-level state persists between invocations

request_count = 0

db_connection = None

def handler(event, context):

global request_count, db_connection

request_count += 1 # Accumulates across warm invocations!

print(f"This environment has handled {request_count} requests")

# Connection reuse - don't recreate on every call

if db_connection is None:

db_connection = create_connection() # Only on cold start

return {'statusCode': 200}Not guaranteed - AWS may terminate environment at any time. In practice, warm environments handle many invocations before termination.

Environment reuse is why:

- Database connection pooling works

- Cached data persists between calls

- Global state accumulates (sometimes unexpectedly)

Patterns for Initialization Code

Move expensive operations outside handler

# GOOD: Initialize once, reuse across invocations

import boto3

import pickle

# These run once per cold start

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

dynamodb = boto3.resource('dynamodb')

table = dynamodb.Table('users')

# Load model once

response = s3.get_object(Bucket='models', Key='model.pkl')

model = pickle.loads(response['Body'].read())

def handler(event, context):

# Fast: uses pre-initialized resources

prediction = model.predict(event['features'])

table.put_item(Item={'id': event['id'], 'result': prediction})

return {'statusCode': 200}Lazy initialization for conditional use

# Resources only initialized if needed

_heavy_client = None

def get_heavy_client():

global _heavy_client

if _heavy_client is None:

_heavy_client = create_expensive_client()

return _heavy_client

def handler(event, context):

if event.get('needs_heavy_processing'):

client = get_heavy_client() # Only init if needed

# ...Understand what initializes when

import json

import boto3 # Import runs during init

# Module level - runs once per cold start

print("Cold start - initializing")

config = load_config()

client = boto3.client('s3')

def helper_function(x):

# Defined at module level

# Body runs when called

return x * 2

def handler(event, context):

# This runs on every invocation

print("Handler executing")

# Function call happens during invocation

result = helper_function(event['value'])

# But client was already created

client.put_object(...) # Uses existing clientCold start output:

Cold start - initializing

Handler executingSubsequent warm invocations:

Handler executingThe initialization message only appears on cold starts.

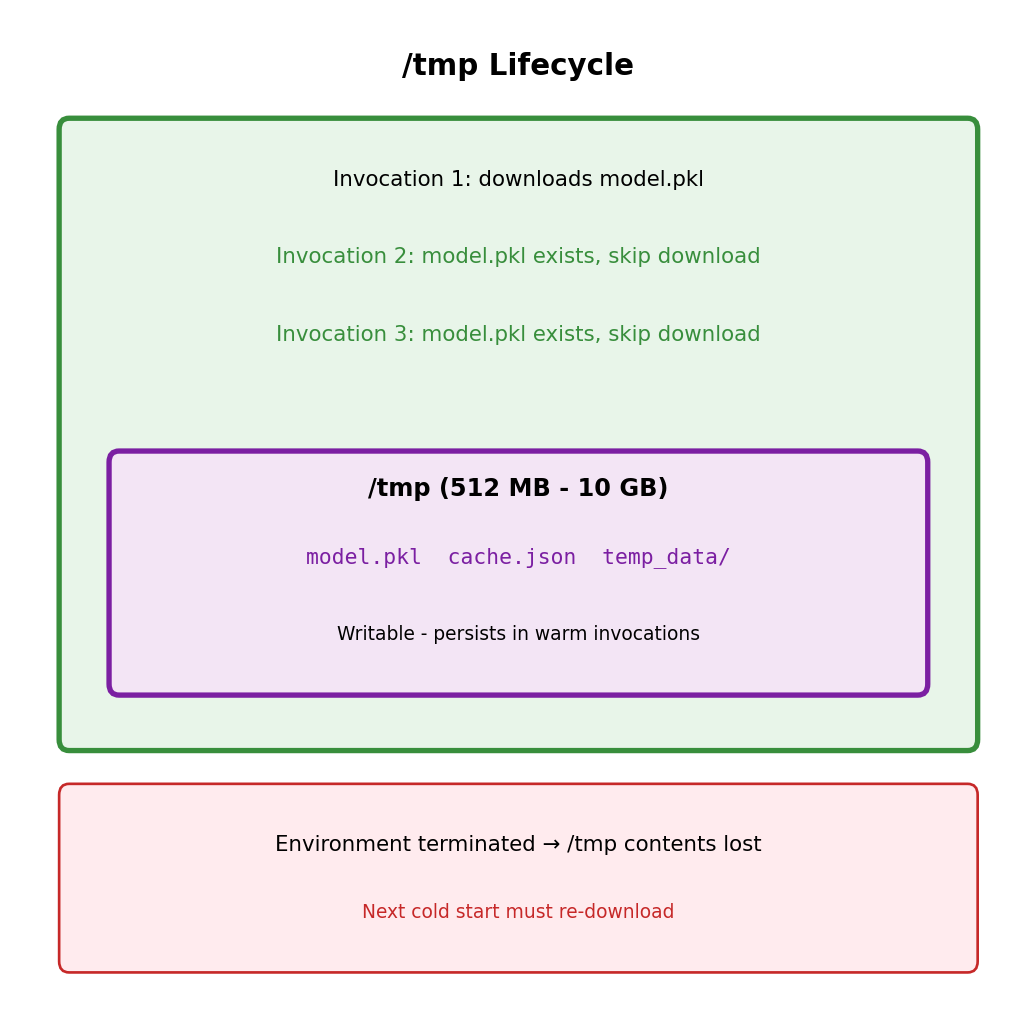

/tmp Storage: Ephemeral but Persistent Within Environment

Writable filesystem in the execution environment

/tmp directory: 512 MB to 10 GB (configurable). Only writable location - code package is read-only.

import os

import tempfile

def handler(event, context):

# Can write to /tmp

with open('/tmp/cache.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(event, f)

# Can read it back

with open('/tmp/cache.json', 'r') as f:

data = json.load(f)

# Check space

statvfs = os.statvfs('/tmp')

available_mb = (statvfs.f_frsize * statvfs.f_bavail) / (1024 * 1024)

print(f"Available /tmp space: {available_mb:.1f} MB")

return {'statusCode': 200}Persistence characteristics:

- Persists across warm invocations (same environment)

- Lost when environment terminates

- Not shared between concurrent invocations (separate environments)

Use for: cached downloads, intermediate processing, temporary data. Don’t rely on for persistence - environment termination not in your control.

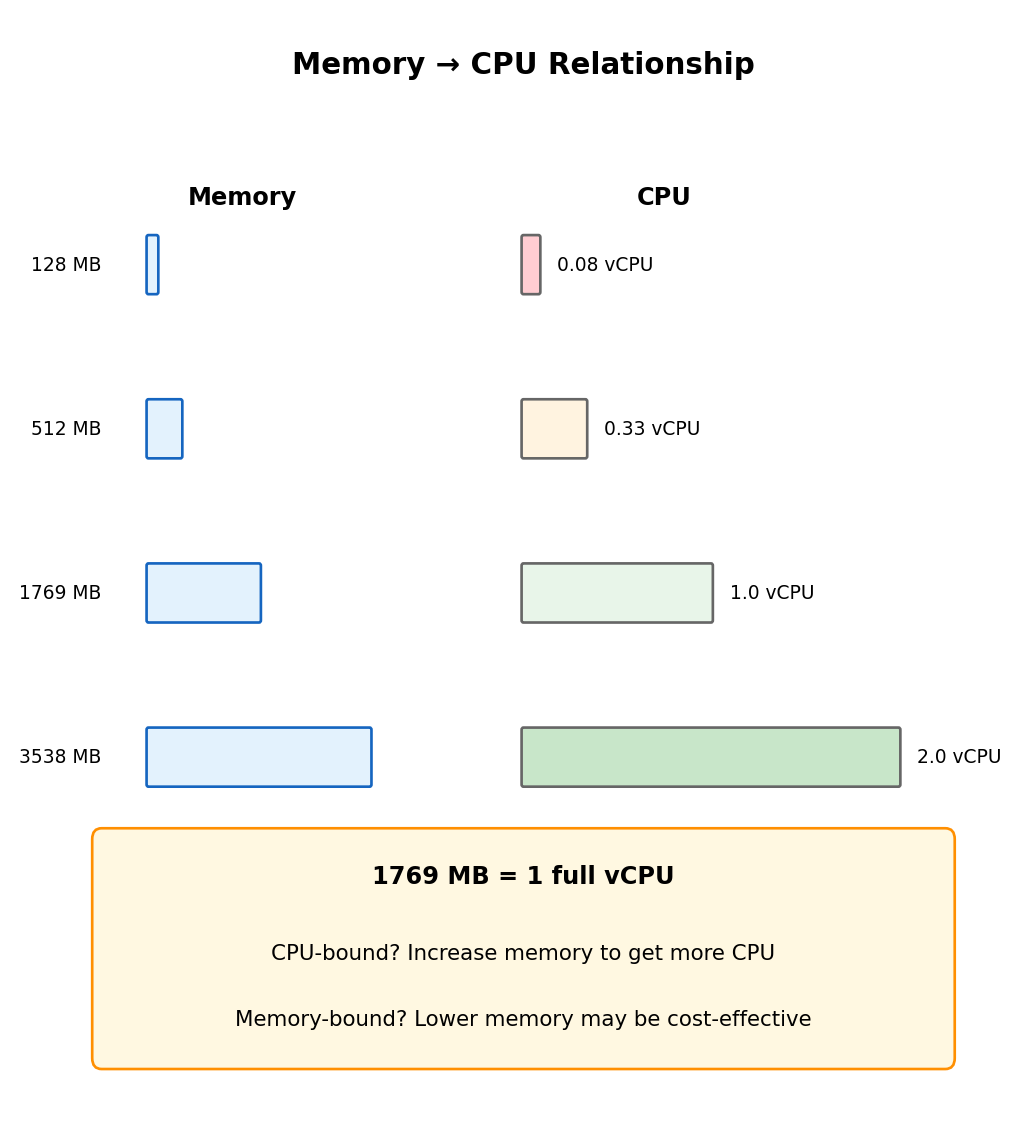

Memory Configuration Determines CPU Allocation

Memory and CPU are proportionally coupled

Configure memory (128 MB to 10 GB). Lambda allocates CPU proportionally - no direct CPU selection.

| Memory | vCPU Equivalent |

|---|---|

| 128 MB | ~0.08 vCPU |

| 512 MB | ~0.33 vCPU |

| 1769 MB | 1 vCPU |

| 3538 MB | 2 vCPU |

| 10240 MB | 6 vCPU |

Implication: CPU-bound work (ML inference, image processing) needs more memory to get more CPU - even if the work doesn’t need the memory.

# If this is slow at 512 MB

def handler(event, context):

# CPU-intensive work

result = expensive_computation(event['data'])

return result

# Increasing to 2048 MB makes it ~4x faster

# Not because we need memory, but because we get more CPUMemory also affects cold start speed:

Higher memory = more CPU = faster initialization. Heavy imports may have faster cold starts at higher memory - potentially reducing total cost despite higher per-ms price.

Timeout: Hard Limit on Execution Duration

Functions have a maximum execution time

Configurable: 1 second to 15 minutes. Function doesn’t complete in time → Lambda terminates it.

def handler(event, context):

# Check remaining time

remaining_ms = context.get_remaining_time_in_millis()

print(f"Time remaining: {remaining_ms} ms")

# Long-running work

for item in event['items']:

if context.get_remaining_time_in_millis() < 5000:

# Less than 5 seconds left - stop gracefully

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'body': 'Partial completion - timeout approaching'

}

process_item(item)

return {'statusCode': 200, 'body': 'Complete'}Timeout termination:

- Function stops immediately (mid-execution)

- No cleanup code runs

- Invocation marked as error

- Any partial work may be lost

Setting appropriate timeouts:

- Too short: unnecessary failures

- Too long: hung functions consume resources, cost money

- Rule of thumb: expected duration + buffer for variability

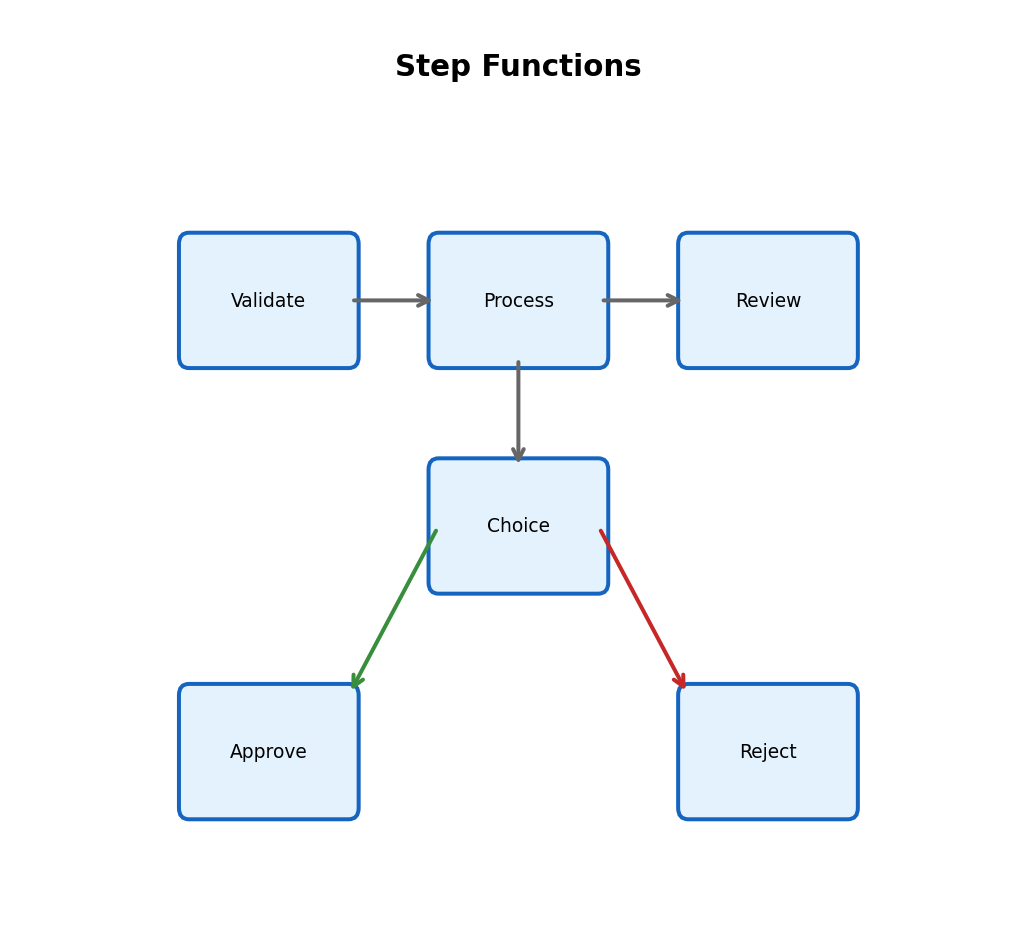

Typical values: API handlers 10-30s, batch processing up to 15 min. Need longer? Use Step Functions or break into smaller pieces.

Environment Variables and Configuration

Configuration without code changes

Environment variables: different configurations per deployment stage, no code changes.

import os

# Read configuration from environment

TABLE_NAME = os.environ['DYNAMODB_TABLE']

LOG_LEVEL = os.environ.get('LOG_LEVEL', 'INFO')

API_ENDPOINT = os.environ['EXTERNAL_API_URL']

def handler(event, context):

# Use configuration

dynamodb.Table(TABLE_NAME).put_item(...)Set via console, CLI, or infrastructure code:

aws lambda update-function-configuration \

--function-name my-function \

--environment "Variables={DYNAMODB_TABLE=prod-users,LOG_LEVEL=WARNING}"Environment per stage:

| Variable | Development | Production |

|---|---|---|

| DYNAMODB_TABLE | dev-users | prod-users |

| LOG_LEVEL | DEBUG | WARNING |

| API_ENDPOINT | https://sandbox.api.com | https://api.com |

Same code, different configuration per deployment.

Secrets handling

Environment variables visible in console and logs. For sensitive values → AWS Secrets Manager or Parameter Store.

import boto3

import os

# NOT this - secret visible in Lambda console

API_KEY = os.environ['API_KEY'] # Visible!

# Better - retrieve at runtime

secrets = boto3.client('secretsmanager')

def get_api_key():

response = secrets.get_secret_value(

SecretId='my-api-key'

)

return response['SecretString']

# Can cache in module scope for reuse

_api_key = None

def handler(event, context):

global _api_key

if _api_key is None:

_api_key = get_api_key()

# Use _api_key securelyEnvironment variables: Non-sensitive configuration (table names, endpoints, feature flags).

Secrets Manager: Credentials, API keys, connection strings.

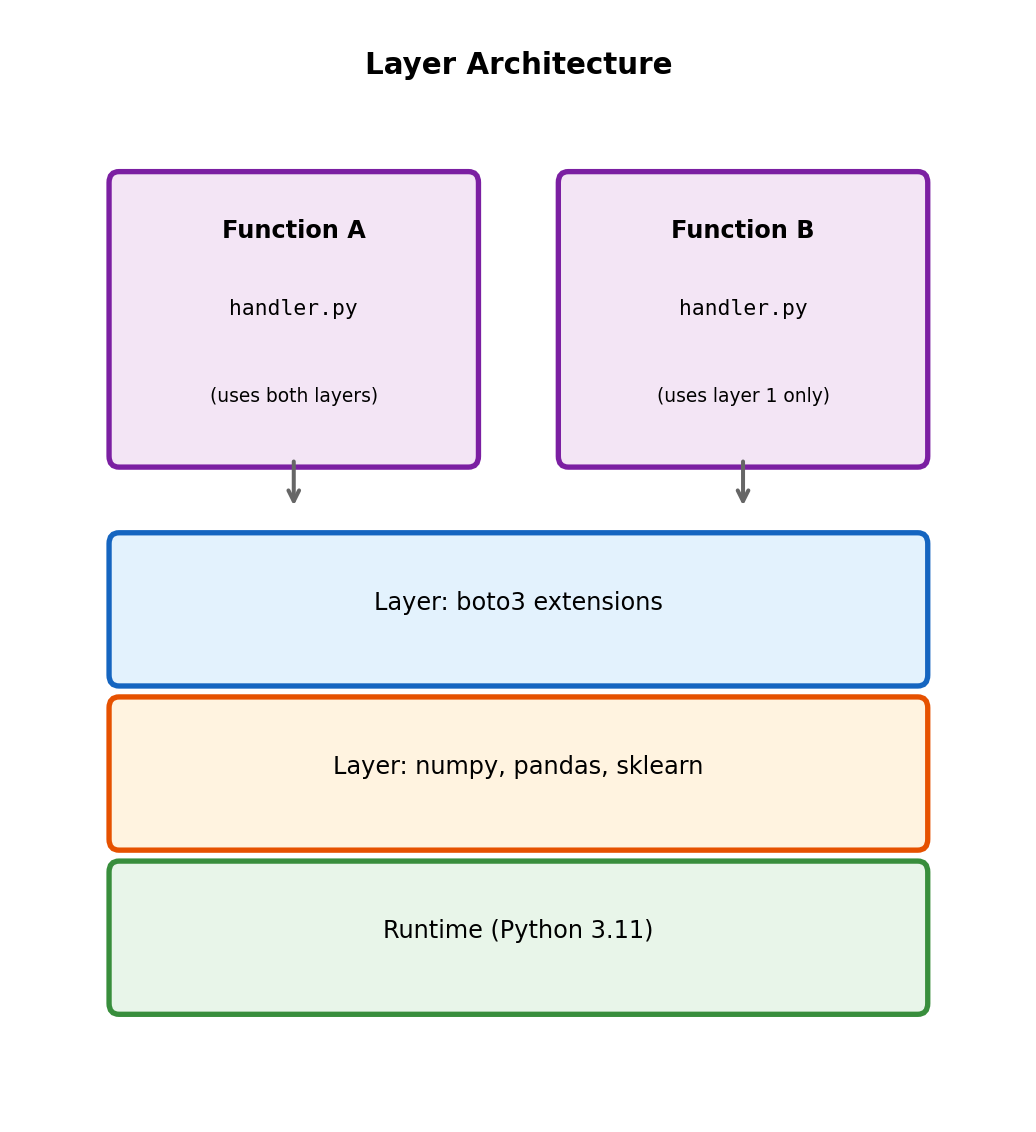

Layers: Shared Code Across Functions

Deployment package structure

Lambda code lives in a deployment package - handler plus dependencies:

Multiple functions with same dependencies → each includes them separately.

Layers separate shared dependencies

Layer: ZIP archive with libraries, custom runtimes, or other dependencies. Functions reference layers instead of bundling everything.

# Function just imports - layer provides the packages

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn import ensemble

def handler(event, context):

# Libraries from layer are available

df = pd.DataFrame(event['data'])

...Layer benefits:

- Smaller function packages (faster deploys)

- Share dependencies across functions

- Update dependencies separately from code

- AWS provides managed layers (e.g., pandas, numpy)

Functions can use up to 5 layers. Total unzipped size (function + layers) limited to 250 MB.

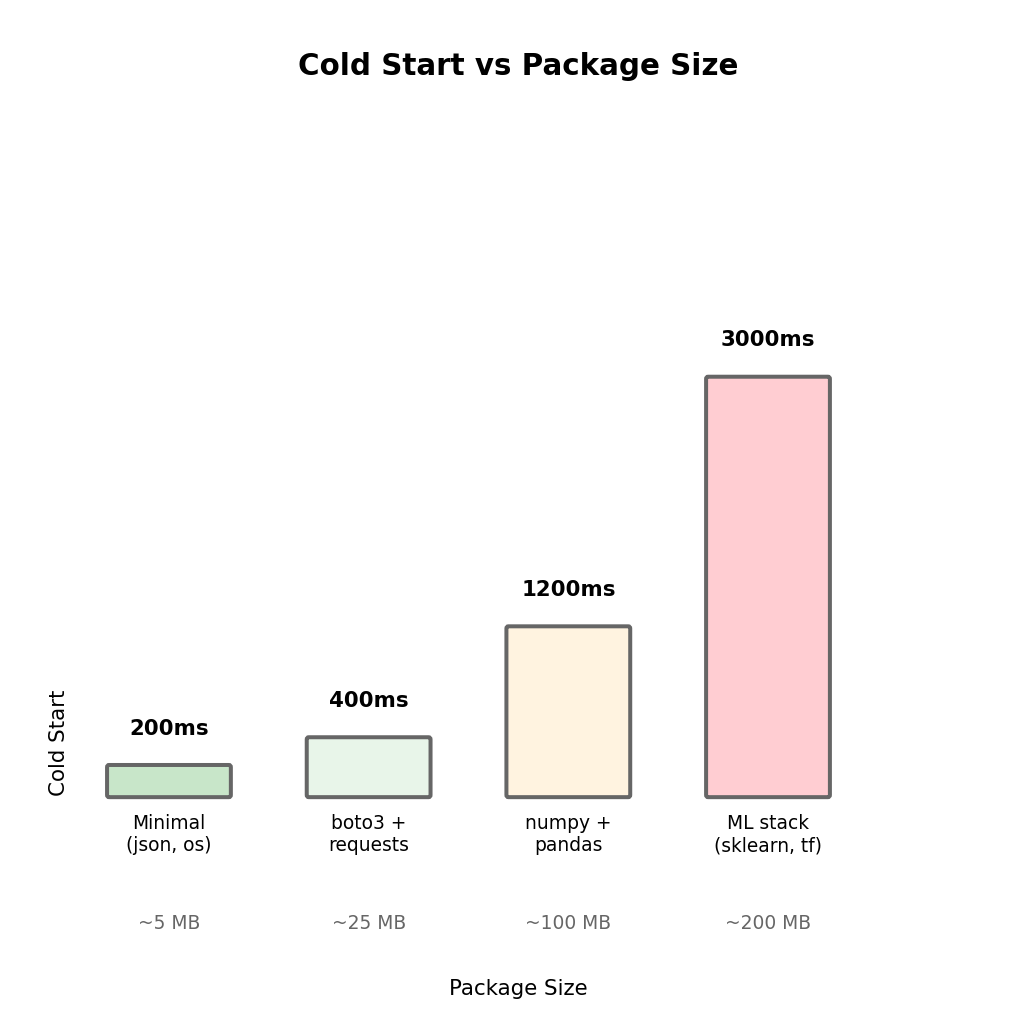

Dependency Size Affects Cold Start

Cold start must download and load your code. More dependencies means:

- Larger download

- More imports to process

- More memory to load modules

Larger packages = longer cold starts

# Minimal dependencies - fast cold start (~200ms)

import json

def handler(event, context):

return {'statusCode': 200, 'body': json.dumps(event)}# Heavy dependencies - slow cold start (~2000ms)

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

import tensorflow as tf

def handler(event, context):

# ...Import granularity matters:

# Imports entire sklearn package

from sklearn import *

# Only loads ensemble module

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifierLazy imports defer cost to when needed:

The relationship isn’t linear - some libraries are particularly slow to import (pandas, tensorflow) due to their own initialization logic.

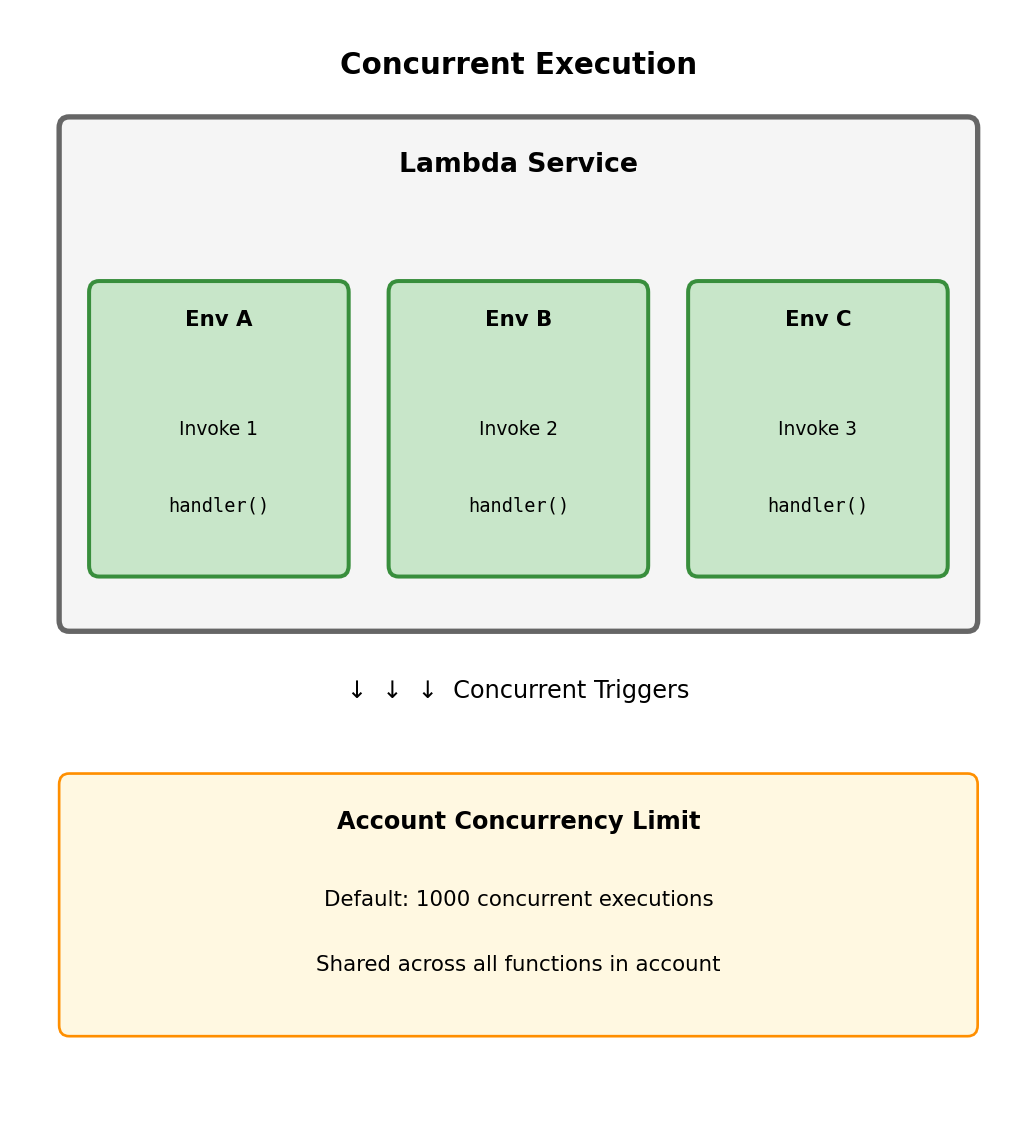

Concurrency: Parallel Execution Environments

When Lambda receives concurrent triggers, it creates additional execution environments. Each concurrent invocation runs in its own isolated environment.

Multiple triggers can arrive simultaneously

Time 0: Trigger 1 arrives → Environment A handles it

Time 10ms: Trigger 2 arrives → Environment B handles it (A still busy)

Time 20ms: Trigger 3 arrives → Environment C handles it

Time 50ms: Trigger 1 completes → Environment A becomes free

Time 60ms: Trigger 4 arrives → Environment A handles it (reused)Concurrency scaling:

- Lambda automatically creates environments as needed

- Scales from 0 to thousands concurrently

- Each new environment incurs cold start

- Default account limit: 1000 concurrent executions

Account-level limit:

All Lambda functions in your AWS account share a concurrency pool. If you have 10 functions and 1000 limit, they collectively can’t exceed 1000 concurrent executions.

Reserved and Provisioned Concurrency

These features exist but add cost and complexity. Most Lambda workloads don’t need them - understand when they’re actually warranted.

Reserved concurrency: Guarantee + Limit

Reserve a portion of account concurrency for specific function. Other functions cannot consume this allocation.

Account limit: 1000

Function A reserved: 200

Function B reserved: 100

Unreserved pool: 700

Function A can use up to 200 (guaranteed)

Function A cannot exceed 200 (limited)

Other functions share remaining 700Use reserved concurrency when:

- Function could overwhelm downstream systems without limit

- Function is critical and must have guaranteed capacity

- You need to prevent one function from starving others

Not needed when: Default scaling behavior is acceptable and downstream systems can handle the load.

Provisioned concurrency: Eliminate cold starts

Keep N execution environments initialized and ready. All invocations up to N are warm.

Provisioned: 10 environments

Invocations 1-10: Instant (pre-warmed)

Invocation 11+: May cold start (scales beyond provisioned)The cost trade-off:

- You pay for provisioned environments even with zero invocations

- Essentially converts Lambda back toward EC2’s cost model

- Negates much of Lambda’s cost advantage for variable traffic

Use provisioned concurrency only when:

- User-facing API where cold start latency is truly unacceptable

- Traffic pattern is predictable enough to provision correctly

- Cost of provisioning is justified by latency requirements

Not needed for: Background processing, async workloads, internal tools, or any function where occasional cold start latency is acceptable.

Lambda Pricing Model

Two pricing components:

- Request charge: Per invocation

- $0.20 per 1 million requests

- Each trigger = one request

- Duration charge: Per GB-second

- $0.0000166667 per GB-second

- GB-second = (memory allocated in GB) × (execution time in seconds)

Example calculation:

Function configuration:

- Memory: 512 MB (0.5 GB)

- Average execution time: 200 ms (0.2 seconds)

- Invocations per month: 1,000,000

Request charges:

1,000,000 requests × $0.20/million = $0.20

Duration charges:

GB-seconds = 0.5 GB × 0.2 sec × 1,000,000 = 100,000 GB-s

100,000 × $0.0000166667 = $1.67

Total monthly cost: $0.20 + $1.67 = $1.87Free tier (per month):

- 1 million requests

- 400,000 GB-seconds

Many low-traffic applications fit entirely in free tier.

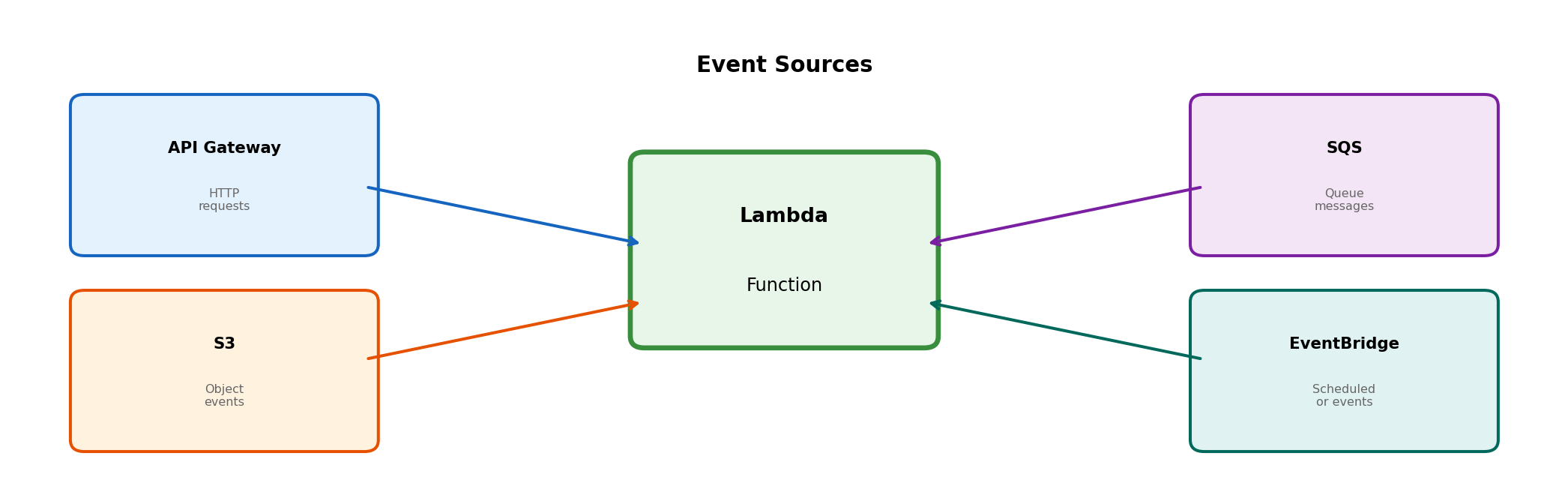

Event Sources That Can Trigger Lambda

Lambda functions execute in response to events. These events come from various sources, each delivering data in a specific format to your handler.

Each source has different characteristics:

| Source | Invocation Type | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| API Gateway | Synchronous - waits for response | HTTP APIs, webhooks |

| S3 | Asynchronous - fire and forget | File processing, uploads |

| SQS | Poll-based - Lambda pulls messages | Work queues, decoupling |

| EventBridge | Asynchronous | Scheduled tasks, event routing |

The invocation type affects how errors are handled and how your function should respond.

HTTP Requests via API Gateway

API Gateway: HTTP endpoint in front of Lambda

AWS service that accepts HTTP requests, routes to backend services including Lambda. Without it, Lambda has no HTTP endpoint - function exists but no URL to call it.

Integration flow:

- Client sends HTTP request to API Gateway URL

- API Gateway transforms request into Lambda event

- API Gateway invokes Lambda function (synchronous)

- Lambda returns response

- API Gateway transforms response to HTTP response

- Client receives HTTP response

Client → API Gateway → Lambda → Response → Client

(HTTP) (invoke) (return) (HTTP)API Gateway handles:

- HTTPS termination (SSL/TLS)

- Request validation

- Authentication/authorization (optional)

- Rate limiting (optional)

- CORS headers

Lambda handles:

- Business logic

- Response generation

API Gateway Event Structure

When API Gateway invokes your Lambda function, it sends an event object containing request details:

def handler(event, context):

# event contains the HTTP request details

# HTTP method and path

http_method = event['httpMethod'] # 'GET', 'POST', etc.

path = event['path'] # '/users/123'

# Query string parameters

params = event.get('queryStringParameters') or {}

page = params.get('page', '1')

# Request headers

headers = event.get('headers') or {}

auth_token = headers.get('Authorization')

content_type = headers.get('Content-Type')

# Request body (for POST/PUT)

body = event.get('body') # String - parse JSON if needed

if body and content_type == 'application/json':

import json

data = json.loads(body)

# Path parameters (from URL like /users/{id})

path_params = event.get('pathParameters') or {}

user_id = path_params.get('id')

# Return HTTP response

return {

'statusCode': 200,

'headers': {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

},

'body': json.dumps({'user_id': user_id, 'page': page})

}The response must include statusCode and body. Headers are optional but commonly needed for Content-Type and CORS.

S3 Events: Object-Triggered Invocation

S3 can trigger Lambda on object changes

Configure bucket to emit events on object create/delete/modify. Lambda subscribes to these events.

Common trigger patterns:

s3:ObjectCreated:*- Any object creation (PUT, POST, Copy)s3:ObjectRemoved:*- Any object deletions3:ObjectCreated:Put- Specifically PUT operations

Event configuration can filter by prefix/suffix:

Trigger: s3:ObjectCreated:*

Prefix: uploads/

Suffix: .jpg

Only triggers for: uploads/*.jpg

Does not trigger for: uploads/doc.pdf or images/photo.jpgInvocation is asynchronous:

S3 emits event and continues - doesn’t wait for Lambda. If Lambda fails, S3 doesn’t know or retry. Lambda service handles retries (twice by default).

Use cases:

- Image uploaded → generate thumbnails

- CSV uploaded → process and load to database

- Log file uploaded → parse and index

- Backup file uploaded → validate and catalog

S3 Event Structure

When S3 triggers your Lambda, the event contains information about what changed:

def handler(event, context):

# event['Records'] is a list - can batch multiple events

for record in event['Records']:

# Event type

event_name = record['eventName'] # 'ObjectCreated:Put'

# Bucket information

bucket = record['s3']['bucket']['name'] # 'my-uploads-bucket'

# Object information

key = record['s3']['object']['key'] # 'uploads/photo.jpg'

size = record['s3']['object']['size'] # 1234567 (bytes)

# Key is URL-encoded - decode it

from urllib.parse import unquote_plus

decoded_key = unquote_plus(key) # Handles spaces, special chars

# Now process the object

if event_name.startswith('ObjectCreated'):

process_new_object(bucket, decoded_key, size)

elif event_name.startswith('ObjectRemoved'):

cleanup_removed_object(bucket, decoded_key)

def process_new_object(bucket, key, size):

import boto3

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# Download the object that triggered this event

response = s3.get_object(Bucket=bucket, Key=key)

content = response['Body'].read()

# Process content...The event tells you what changed. Your handler retrieves the actual content from S3 if needed.

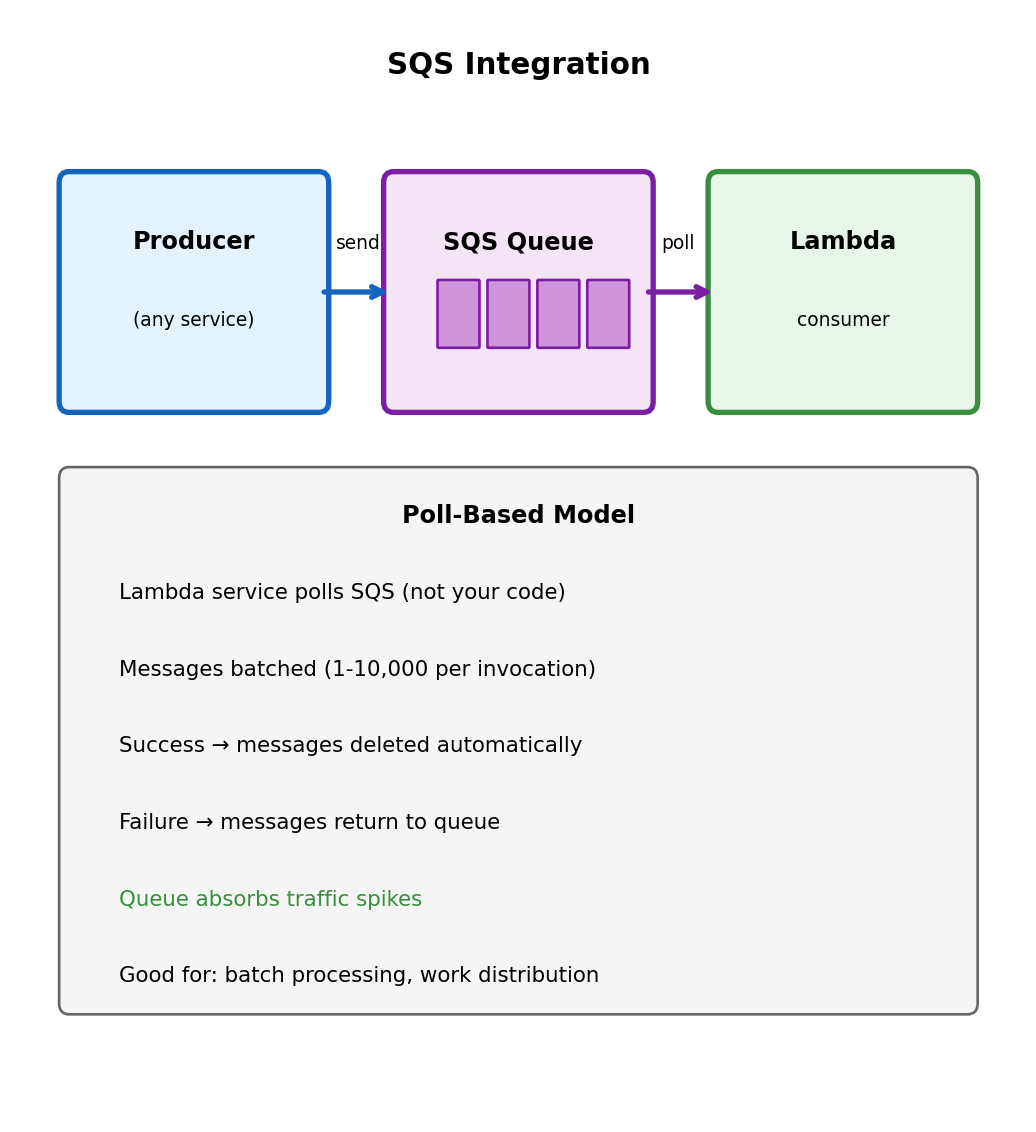

SQS: Poll-Based Invocation

SQS (Simple Queue Service) decouples producers and consumers

Messages placed in queue. Lambda polls and processes. Different from API Gateway (synchronous push) and S3 (asynchronous push).

Why queue-based processing?

- Decoupling: Producer doesn’t need to know about consumer

- Buffering: Queue absorbs traffic spikes

- Retry: Failed messages return to queue

- Rate control: Control how fast Lambda processes

Lambda polls SQS (you don’t):

Lambda service manages polling. Messages available → invokes your function with a batch.

def handler(event, context):

# event['Records'] contains batch of messages

for record in event['Records']:

body = record['body'] # Message content

# Process message

data = json.loads(body)

process_item(data)

# Successful return = messages deleted from queue

# Exception = messages return to queue for retryBatch processing:

Multiple messages per invocation (configurable 1-10,000). Efficient for high-volume queues - one cold start handles many messages.

When Lambda Fits

Lambda is not universally better or worse than EC2 - it has characteristics that fit certain patterns well.

Lambda fits well:

Event-driven processing

- File uploaded → process it

- HTTP request → respond

- Message received → handle it

- Schedule → run task

Variable/unpredictable traffic

- Sporadic API calls

- Batch jobs that run occasionally

- Development/testing environments

- New products with unknown demand

Short-duration tasks

- API handlers (seconds)

- Data transformation

- Notification sending

- Webhook processing

Operations you don’t want to manage

- No patching

- No capacity planning

- No scaling configuration

- No server monitoring

Lambda fits poorly:

Long-running processes

- 15 minute maximum

- No persistent connections

- No background threads that survive invocation

Consistent high throughput

- EC2 may be more cost-effective

- Reserved capacity costs add up

- Cold starts under load

Specific runtime requirements

- Custom OS configuration

- Specific library versions

- Hardware requirements (GPU)

Stateful applications

- No persistent local state

- No filesystem persistence

- Connection pooling is limited

Latency-critical without provisioning

- Cold starts add latency

- Provisioned concurrency adds cost

The decision isn’t “Lambda vs EC2” but rather “which pattern fits this workload’s characteristics?”

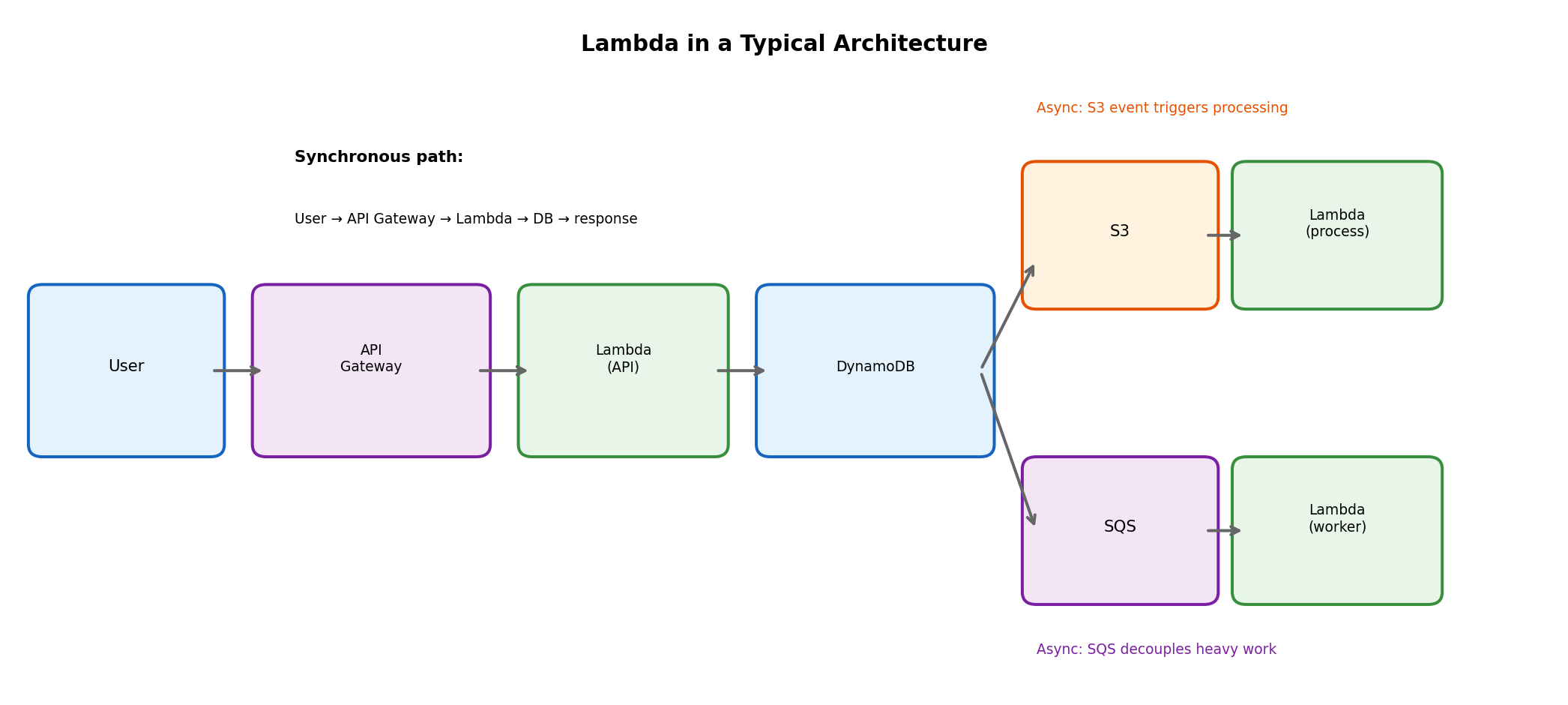

Lambda in System Architecture

Lambda functions rarely exist in isolation - they connect to other services to form complete systems.

Common integration patterns:

- API Gateway → Lambda → DynamoDB: Synchronous API handling

- S3 → Lambda: Trigger processing when files arrive

- SQS → Lambda: Queue-based work processing

- EventBridge → Lambda: Scheduled tasks, event routing

- Lambda → SQS/SNS: Decouple downstream processing

Each function small and focused. Complex workflows: multiple functions with services between them.

Asynchronous Processing

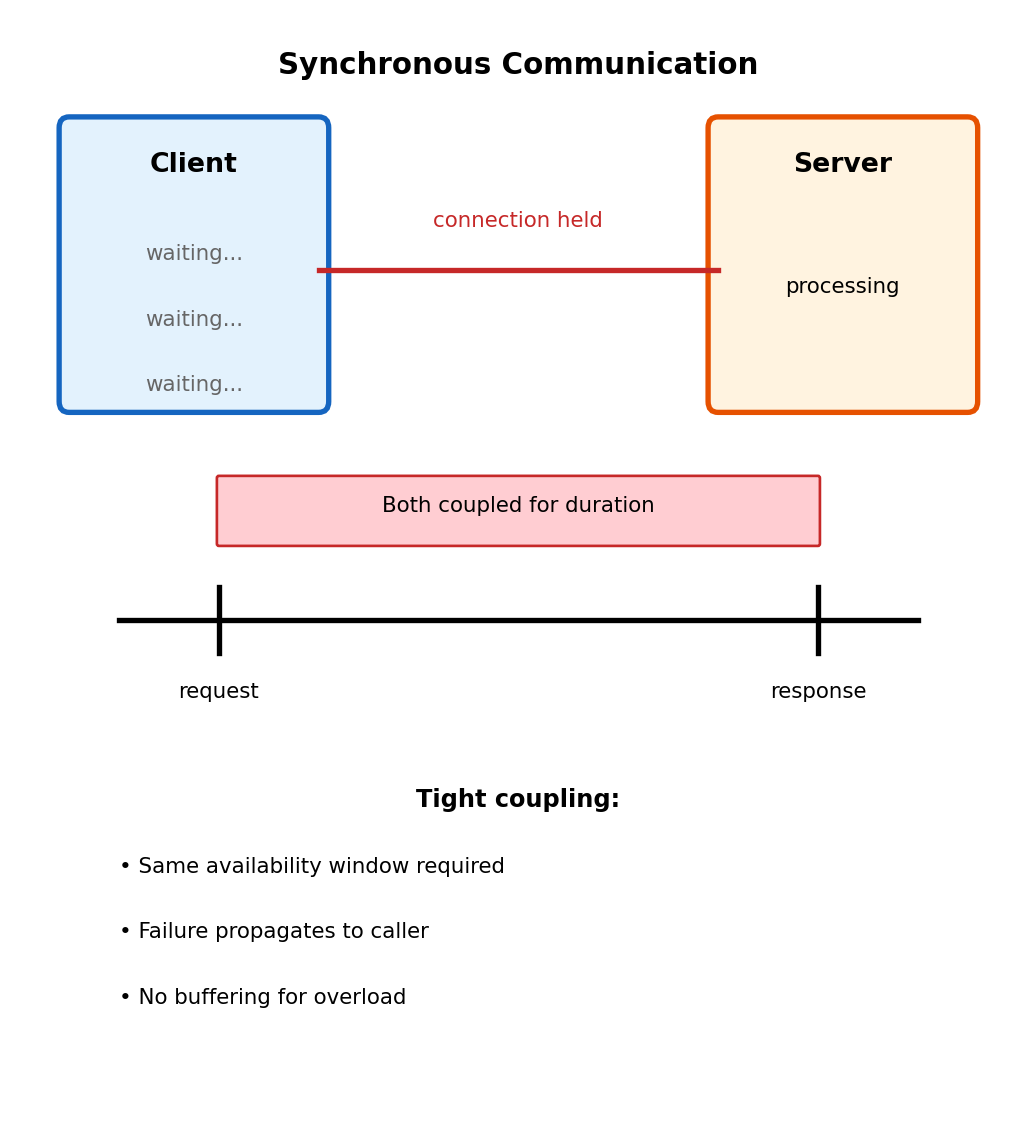

Synchronous Communication: Tight Coupling

Direct call model

def handle_request(request):

order = parse_order(request)

result = process_order(order) # 30 seconds

return resultHTTP connection held entire 30 seconds.

Coupling consequences:

- Client blocks until completion

- Server crash mid-processing → work lost

- Traffic spike beyond capacity → requests rejected

- Both parties must be available simultaneously

When synchronous makes sense:

- User actively waiting (login, search)

- Result needed to proceed

- Processing is fast (sub-second)

The Key Question: Does the Caller Need to Wait?

Must wait for result

- Login form → need auth result to proceed

- Account balance query → user looking at screen

- Search → user waiting for results

Synchronous appropriate here. Coupling inherent to use case.

Can proceed without waiting

- Place order → confirmation enough, fulfillment later

- Upload video → don’t wait for transcoding

- Generate report → check back later

Can decouple request from processing.

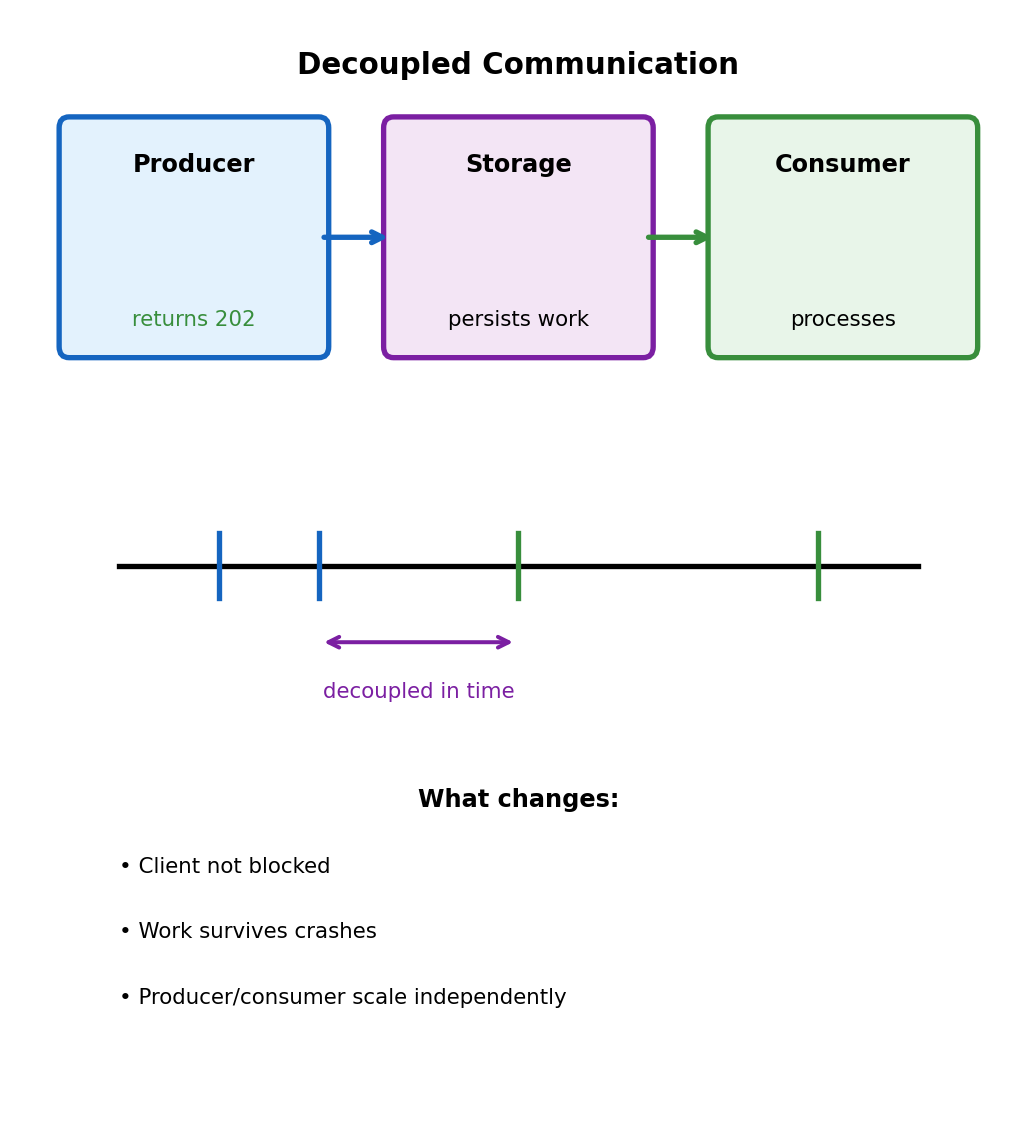

Decoupling in time = separating “request accepted” from “request completed”

Opens architectural options:

- Failure isolation

- Load buffering

- Independent scaling

- Different availability requirements

Decoupling via Intermediate Storage

Instead of A → B directly: A → Storage → B

# Producer: accept and acknowledge

def handle_request(request):

job_id = str(uuid.uuid4())

store_job(job_id, request.data)

return {'job_id': job_id, 'status': 'accepted'}, 202

# Consumer: process from storage (separate process)

def process_pending_jobs():

while True:

job = get_next_job()

if job:

result = do_processing(job)

save_result(job.id, result)

mark_complete(job.id)HTTP 202 (Accepted) vs 200 (OK):

- 202 = “accepted your request”

- 200 = “completed your request”

Client checks back later or receives callback.

What Properties Does the Storage Need?

Not just any database - specific requirements for reliable async processing:

Durability

- Once accepted, work must not be lost

- Survives producer crash after write

- Survives consumer crash mid-processing

Ordering (sometimes)

- Some workloads: process in order received

- Other workloads: order doesn’t matter

- Trade-off: strict ordering limits throughput

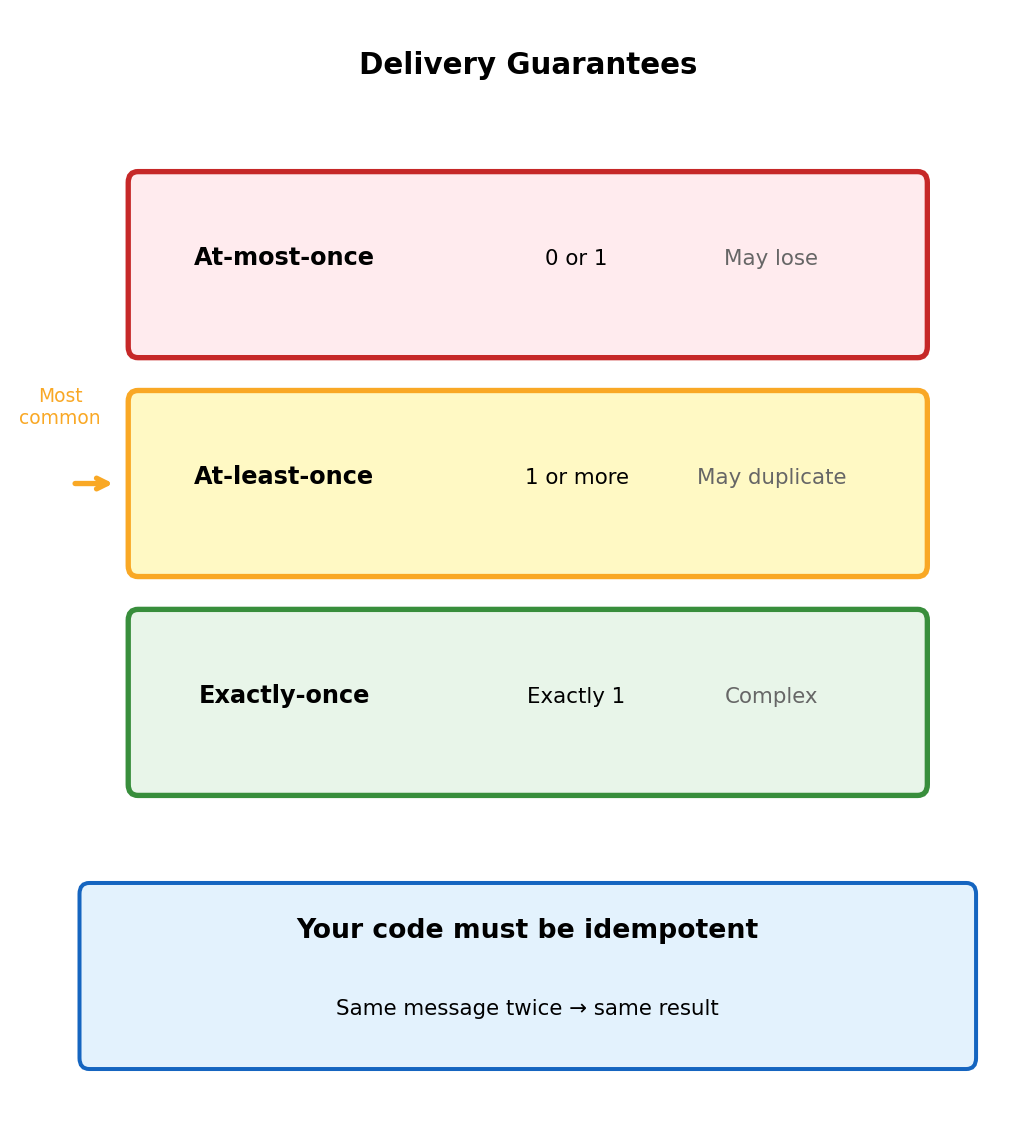

Delivery semantics

What if consumer crashes after receiving?

- At-most-once: Job lost (fast, but loses work)

- At-least-once: Job re-delivered (common choice)

- Exactly-once: Complex, expensive

Visibility control

- Consumer A takes job → B shouldn’t also take it

- But if A crashes → job should become available again

- Need temporary “hide while processing” mechanism

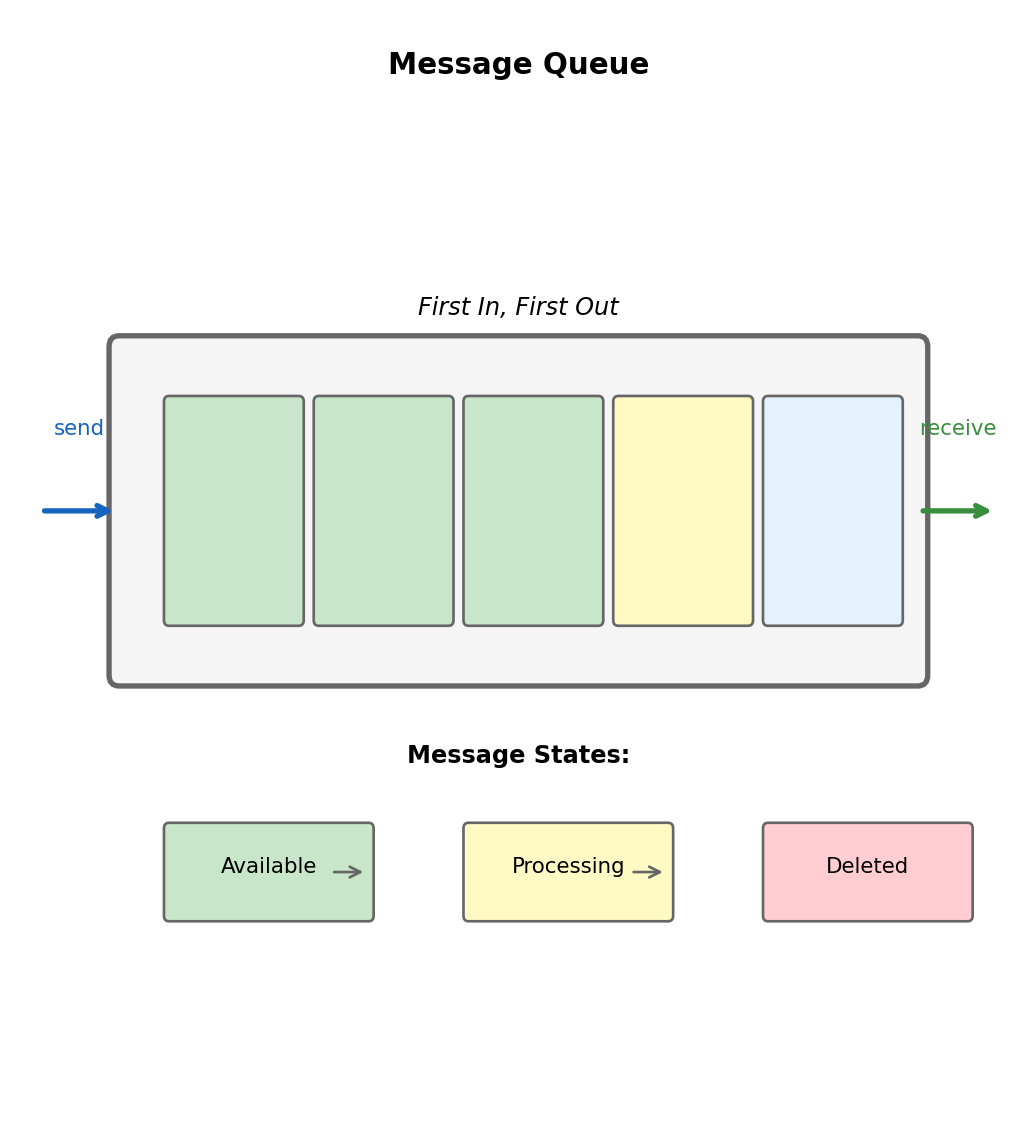

These requirements common enough → dedicated abstraction: message queue

The Message Queue Abstraction

Three fundamental operations

Producer Queue Consumer

| | |

|--- send(msg) ------->| |

| | |

| |<---- receive() -------|

| | |

| | [processing...] |

| | |

| |<---- delete() --------|Send: Add message, returns when durably stored

Receive: Get next message, becomes temporarily invisible

Delete: Confirm complete, permanently removed

Key insight: Message not removed on receive - removed on explicit delete. Enables recovery if consumer fails mid-processing.

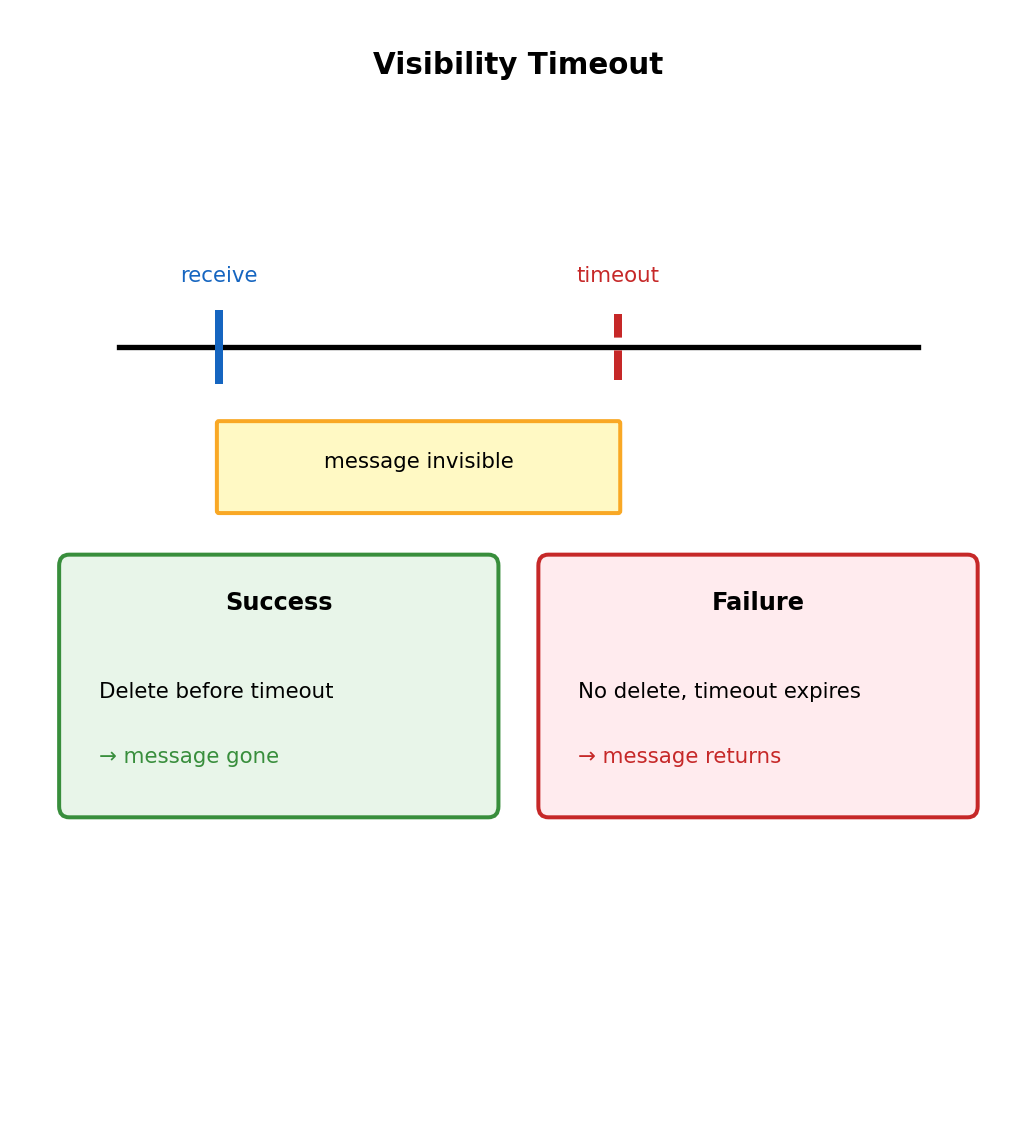

Visibility Timeout

What if consumer receives message then crashes before delete?

Mechanism

On receive → message invisible for configurable period

t=0 Consumer A receives

Message invisible (30s timeout starts)

t=15 Consumer A still processing

Message still invisible

t=35 Timeout expired, no delete

Message visible again

t=36 Consumer B receives

Retry beginsTimeout too short: Message reappears while still being processed → duplicate work

Timeout too long: Failed processing waits unnecessarily before retry

Extending Visibility for Long Processing

Don’t know how long processing takes? Extend timeout during processing:

def process_message(message, queue_client):

receipt_handle = message['ReceiptHandle']

for chunk in large_dataset:

process_chunk(chunk)

# Heartbeat: extend visibility every 20 seconds

queue_client.change_message_visibility(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

ReceiptHandle=receipt_handle,

VisibilityTimeout=30 # Another 30 seconds

)

# Done - delete

queue_client.delete_message(QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL, ReceiptHandle=receipt_handle)Pattern: Consumer “heartbeats” queue = “still working on this”

- Heartbeats stop (crash) → message eventually visible again

- Allows short default timeout (fast recovery) + arbitrarily long processing

At-Least-Once Delivery

Most queues guarantee: message will be delivered, but might be delivered more than once.

How duplicates occur

1. Consumer receives message

2. Processes successfully (30 sec)

3. Sends delete request

4. Network hiccup - delete lost

5. Queue never receives delete

6. Visibility timeout expires

7. Message visible again

8. Another consumer receives

9. Processed twiceConsumer did everything right. Network unreliability caused duplicate.

Not a bug - fundamental trade-off

Exactly-once requires distributed transactions. Complex, expensive. At-least-once is practical choice.

Implication: Your code must handle duplicates.

Idempotent Processing

Idempotent = processing same message twice produces same result as once

Naturally idempotent

# Set absolute value

user.status = 'active'

# Write to specific key

s3.put_object(Bucket='b', Key='k', Body=data)

# Upsert

db.upsert(key=order_id, data=order_data)“Set X to Y” - running twice just sets X to Y twice.

NOT idempotent

Making operations idempotent

Track what you’ve processed:

def process_payment(message):

message_id = message['MessageId']

# Already processed?

if db.get(f'processed:{message_id}'):

return # Skip duplicate

# Process

charge_customer(message['amount'])

# Record completion

db.put(f'processed:{message_id}', {

'processed_at': now()

})Use atomic check-and-set (DynamoDB conditional write) to handle race conditions.

Idempotency Keys for External Services

When calling external services, pass idempotency key:

def process_order_payment(message):

order = json.loads(message['Body'])

# Deterministic key from message content

idempotency_key = f"order-{order['order_id']}-payment"

# Stripe deduplicates based on key

stripe.PaymentIntent.create(

amount=order['amount'],

currency='usd',

idempotency_key=idempotency_key # Same key = same response

)Many payment APIs support this precisely because at-least-once is common.

Best practices:

- Derive from logical identity, not queue-assigned ID

- Include all parameters affecting operation

- Consistent generation (same inputs → same key)

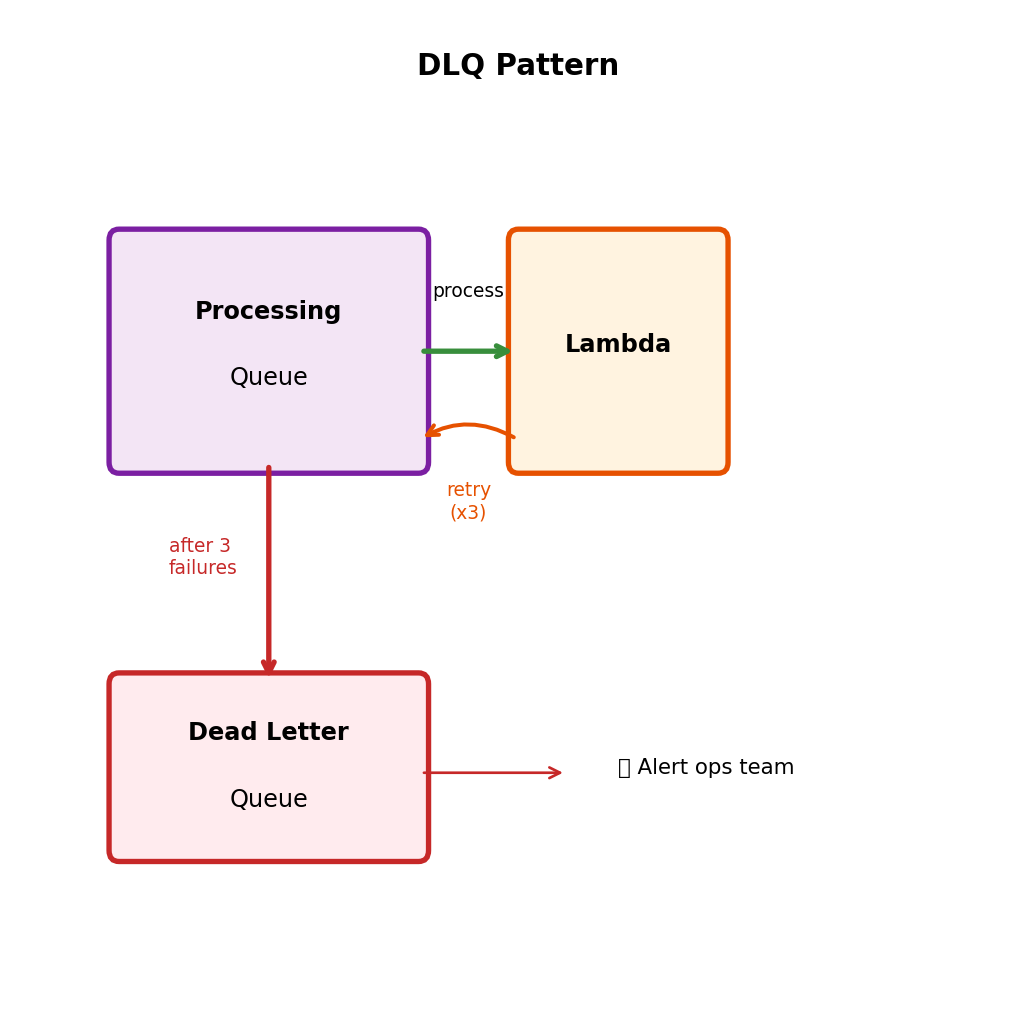

Dead Letter Queues

Some messages can never succeed. Invalid data, deleted resources, bugs.

Poison message problem

Message with malformed JSON arrives

Consumer 1: parse fails, crash

Message returns to queue

Consumer 2: parse fails, crash

Message returns to queue

Consumer 3: parse fails, crash

...forever...Queue keeps delivering, consumers keep failing.

Solution: Dead letter queue (DLQ)

After N failed attempts → move to separate queue

- Isolates problem messages

- Healthy messages continue processing

- DLQ = holding area for investigation

DLQ Configuration and Replay

Max receive count

Each failed processing increments count. After N receives without delete → move to DLQ.

# Check in handler

def handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

count = int(record['attributes']

['ApproximateReceiveCount'])

if count > 3:

log.error(f"Repeated failure: {record}")Typical settings:

- Max receive: 3-5

- Visibility timeout: Match processing time

- DLQ retention: Days to weeks

DLQ depth signals:

- Spike: New bug, bad data batch

- Gradual growth: Intermittent issue

- Constant: Known issue unaddressed

Replay after fixing

def replay_dlq():

"""Move DLQ messages back to main"""

while True:

response = sqs.receive_message(

QueueUrl=DLQ_URL,

MaxNumberOfMessages=10,

WaitTimeSeconds=1

)

messages = response.get('Messages', [])

if not messages:

break

for msg in messages:

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=MAIN_QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=msg['Body']

)

sqs.delete_message(

QueueUrl=DLQ_URL,

ReceiptHandle=msg['ReceiptHandle']

)Only replay after fixing issue, else messages cycle back to DLQ.

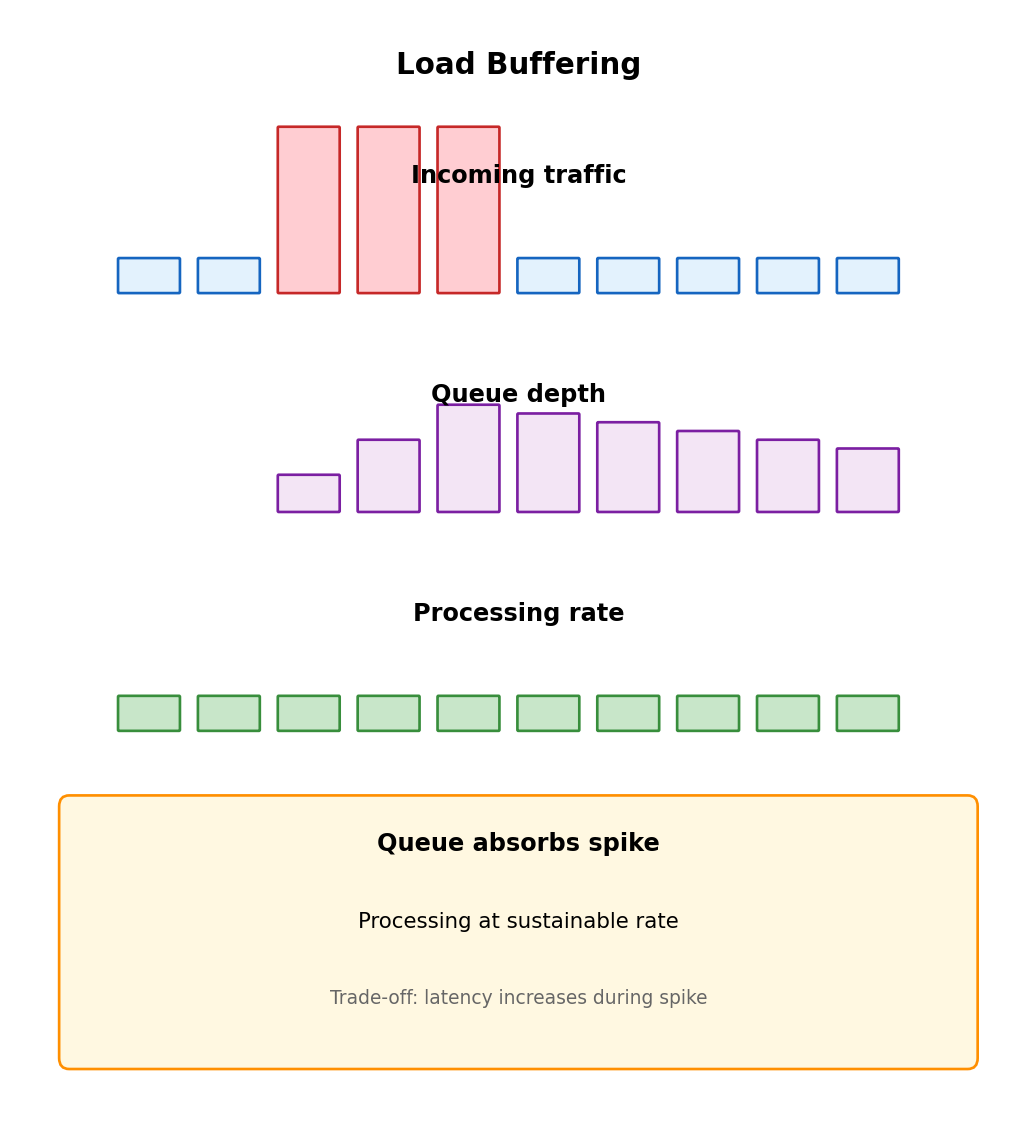

Load Buffering

Queues absorb traffic spikes that exceed processing capacity.

Synchronous under spike

Requests arrive faster than processing capacity:

- Excess requests timeout or rejected

- HTTP 503 Service Unavailable

- Cascading failures as servers overload

Asynchronous under spike

Time Arrivals Queue Processing

00:00 100/sec 0 100/sec

00:01 500/sec 400 100/sec ← spike

00:02 500/sec 800 100/sec

00:03 100/sec 700 100/sec ← spike ends

00:04 100/sec 600 100/sec

...

00:10 100/sec 0 100/sec ← drained- All requests accepted

- Processing rate constant

- Spike absorbed into queue depth

- Gradually drains after spike

Throughput vs Latency Trade-off

Synchronous under load

- Latency constant until capacity hit

- At capacity: reject excess

- Throughput capped

- No backlog after spike

Asynchronous under load

- All requests accepted

- Latency grows with queue depth

- Backlog must drain after spike

- Recovery time depends on spike duration

Neither universally better

- User-facing, latency-sensitive → sync with backpressure

- Background processing, eventual completion OK → async

Hybrid: Accept and queue, but set max depth. Exceed threshold → reject. Buffering for normal spikes, bounded latency.

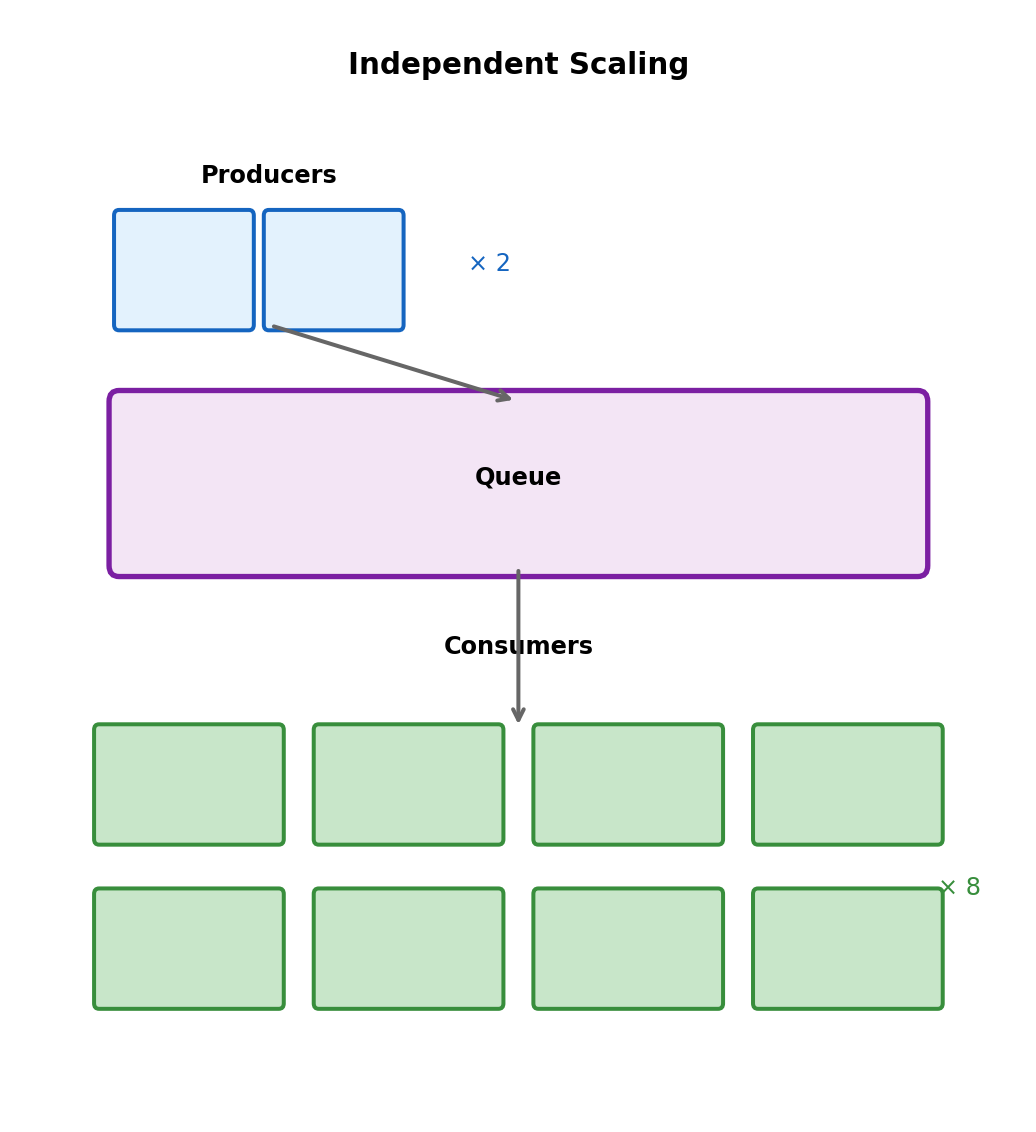

Independent Scaling

Synchronous: Scaling coupled

Same process receives and processes. Add capacity for processing → also add receiving capacity (maybe don’t need).

Queue-based: Scale each tier independently

Producers: 2 instances (receiving is fast)

↓

┌───────────┐

│ Queue │

└───────────┘

↓

Consumers: 8 instances (processing is slow)- Add producers for request volume

- Add consumers for processing throughput

- Remove consumers when queue empty (cost savings)

Lambda auto-scales on queue depth:

- Depth grows → more concurrent executions

- Queue empties → scale to zero

- Pay only for actual processing

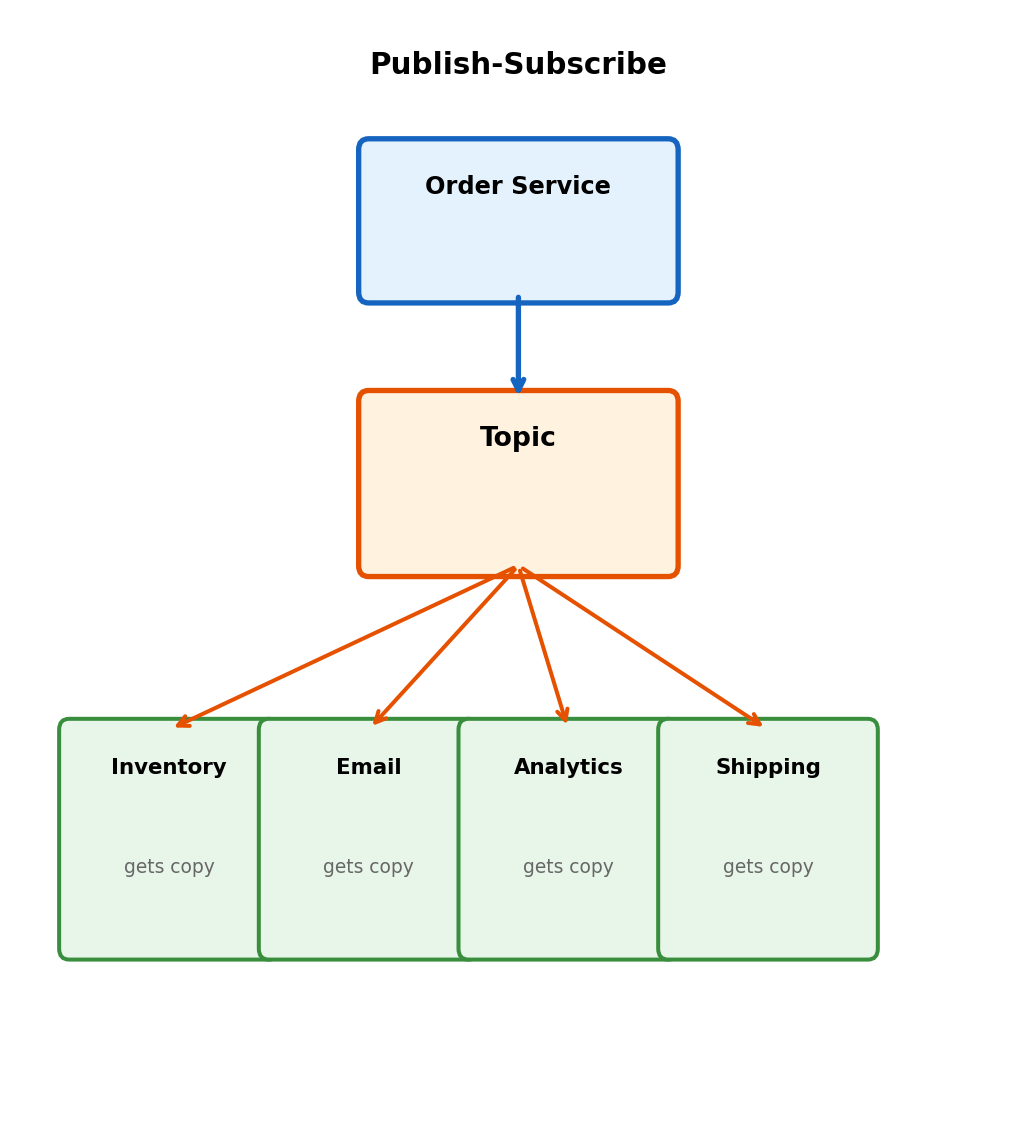

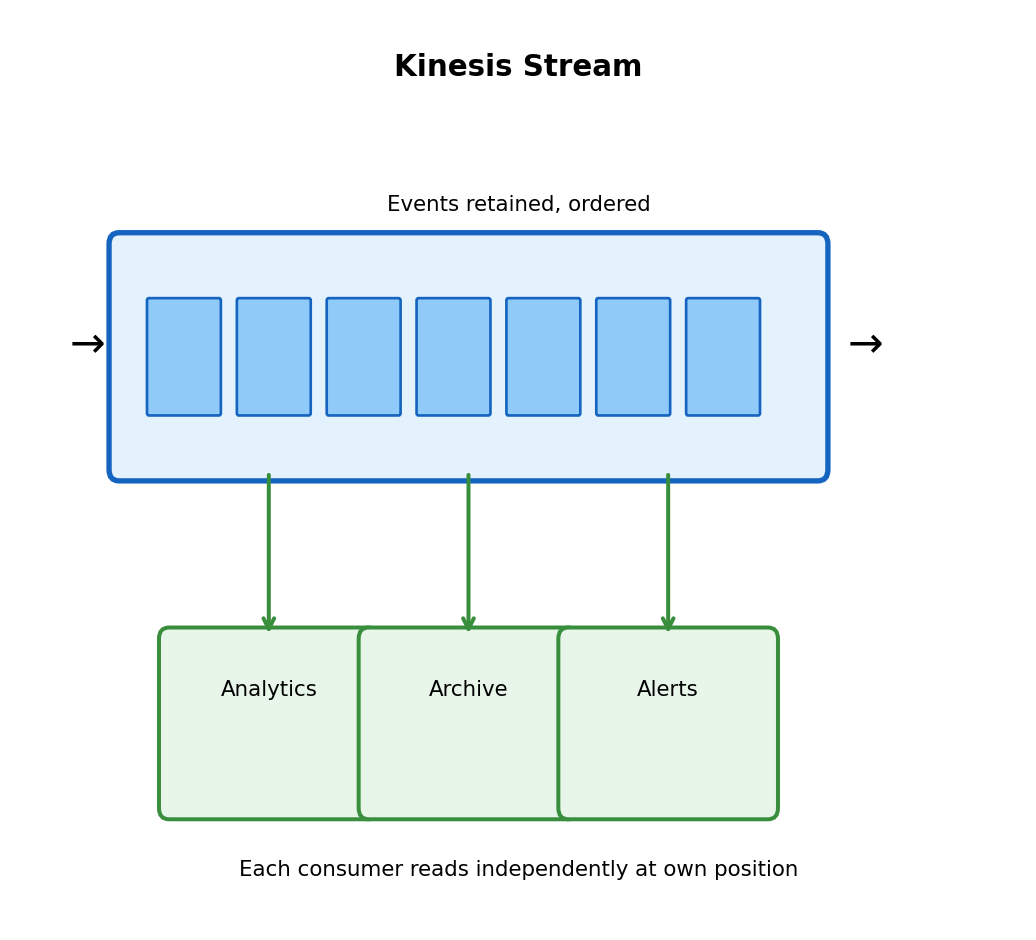

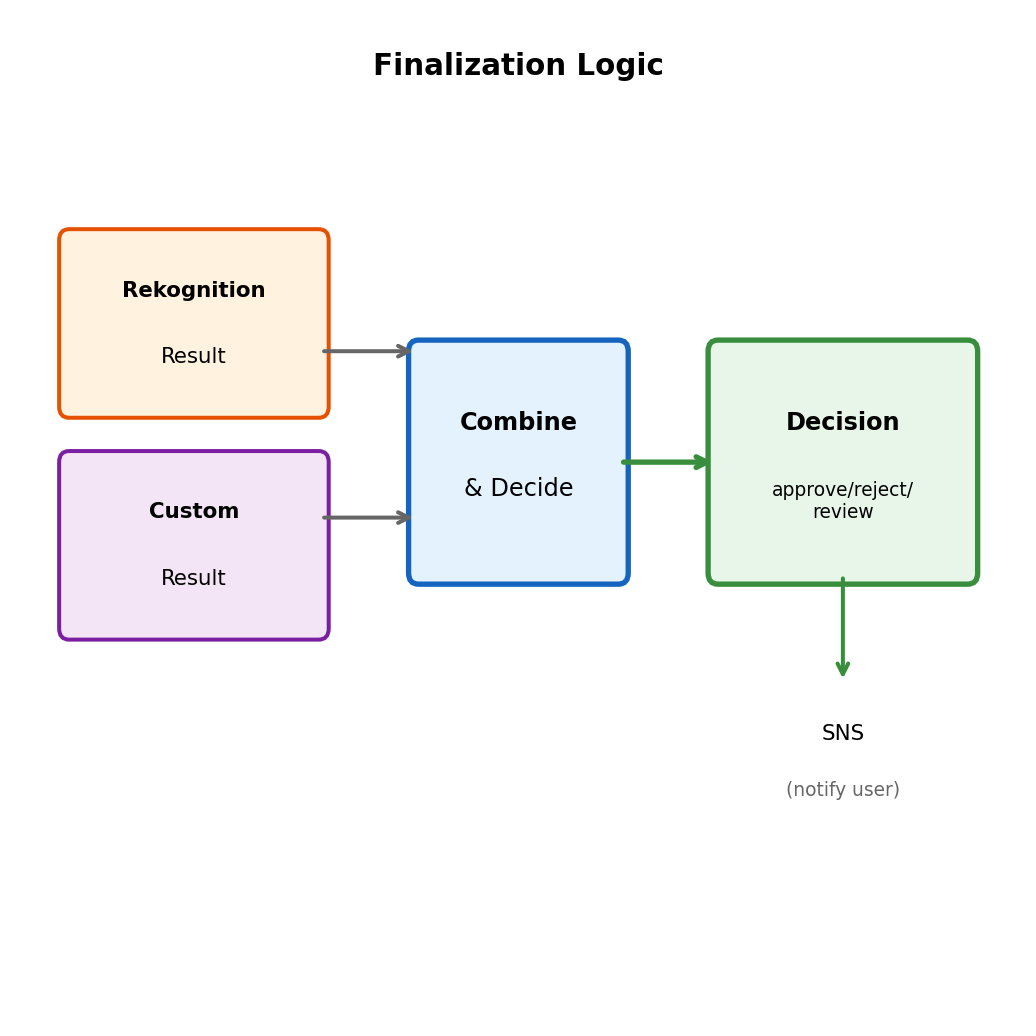

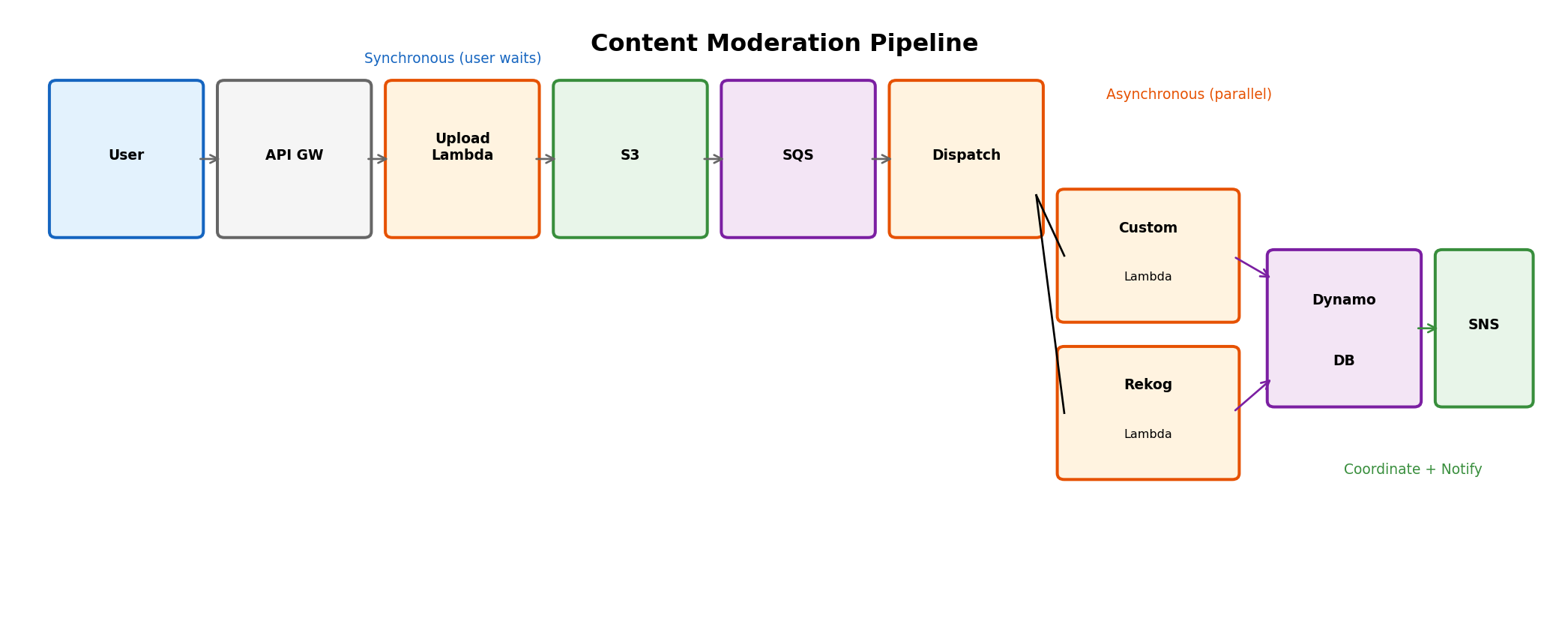

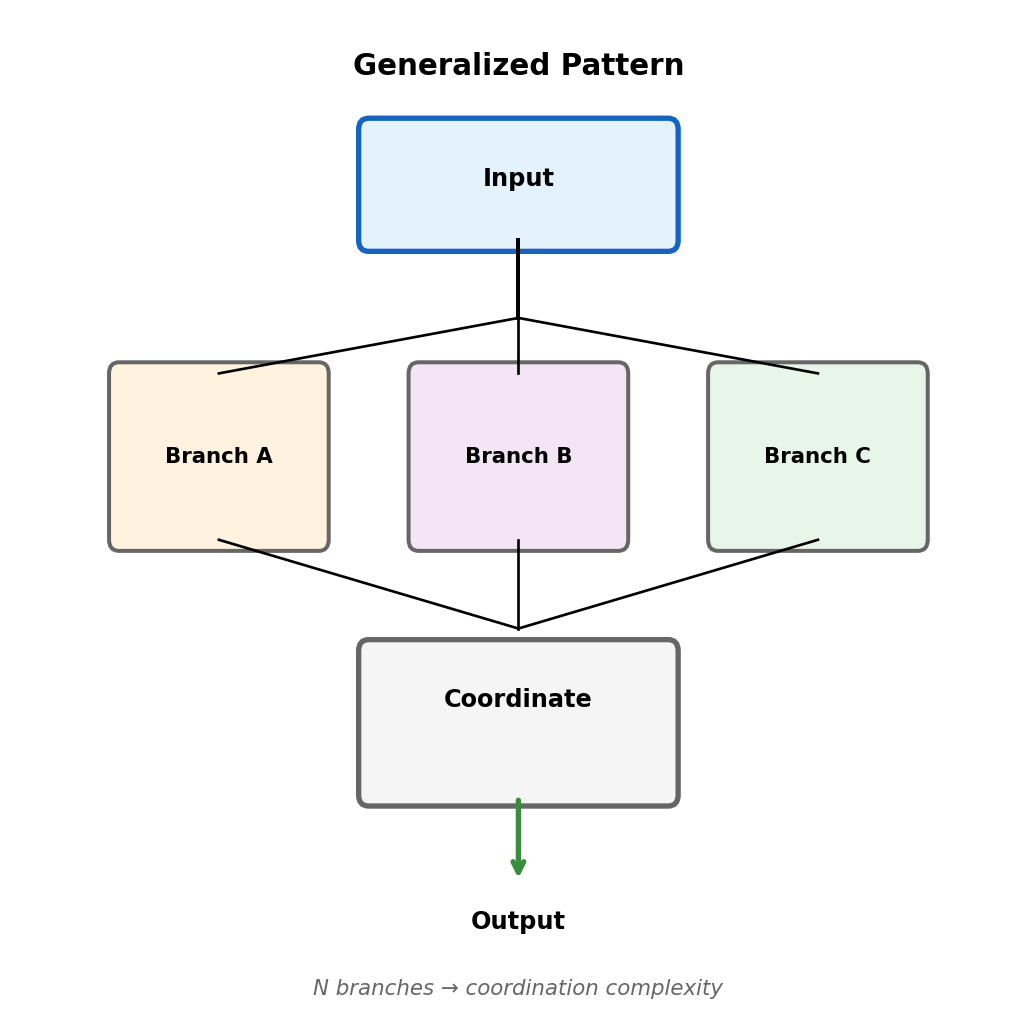

Fan-Out: One Event, Multiple Consumers

Order placed → need to:

- Update inventory

- Send confirmation email

- Record analytics

- Notify shipping

Point-to-point queue

Each message → one consumer. Multiple services need event?

- Producer sends to multiple queues, or

- One consumer forwards to others

Couples producer to knowledge of all consumers.

Publish-subscribe

Producer publishes to topic. All subscribers get copy.

- Publish once

- Add consumer → no producer change

- Producer doesn’t know (or care) who subscribes

Fan-Out + Durability: Topic → Queue → Consumer

Topics alone: no durability. Subscriber unavailable → misses event.

Combined pattern

Each subscriber has own queue subscribed to topic:

Order Service

│

▼

┌────────────┐

│ SNS Topic │ (fan-out)

└────────────┘

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

┌───┐┌───┐┌───┐

│SQS││SQS││SQS│ (durability)

└───┘└───┘└───┘

│ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼

Inv Email Ship (consumers)Benefits:

- Fan-out from topic

- Durability from queues

- Each consumer: own pace, failure isolated

- Add subscriber: create queue, subscribe to topic

# Producer: publish to topic

sns.publish(

TopicArn=ORDER_TOPIC_ARN,

Message=json.dumps({

'order_id': order_id,

'event': 'placed'

})

)

# Consumer: read from own queue

def inventory_handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

# SNS wraps in extra JSON layer

sns_msg = json.loads(record['body'])

order = json.loads(sns_msg['Message'])

update_inventory(order)

# Email service: separate Lambda, separate queue

def email_handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

sns_msg = json.loads(record['body'])

order = json.loads(sns_msg['Message'])

send_confirmation(order)AWS SQS: Standard vs FIFO

Standard Queue

- At-least-once delivery

- Best-effort ordering (usually FIFO, not guaranteed)

- Unlimited throughput

- Cheaper

FIFO Queue

- Exactly-once processing

- Strict ordering guaranteed

- 300-3000 msg/sec limit

- Queue name ends

.fifo

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=FIFO_QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=json.dumps(data),

MessageGroupId='user-123',

MessageDeduplicationId=str(uuid.uuid4())

)Use FIFO when:

- Financial transactions

- User action sequences

- Event sourcing

Default choice: Standard + idempotent processing

AWS SNS: Publish-Subscribe

Topic characteristics

- Push delivery to subscribers

- Subscriber types: SQS, Lambda, HTTP, email, SMS

- All subscribers receive every message

- Message filtering by attributes

- No retention (deliver immediately or lost)

Subscribing

# Subscribe SQS queue

sns.subscribe(

TopicArn=topic_arn,

Protocol='sqs',

Endpoint=queue_arn

)

# Subscribe Lambda

sns.subscribe(

TopicArn=topic_arn,

Protocol='lambda',

Endpoint=function_arn

)

# Subscribe with filter

sns.subscribe(

TopicArn=topic_arn,

Protocol='sqs',

Endpoint=high_value_queue_arn,

Attributes={

'FilterPolicy': json.dumps({

'order_value': [{'numeric': ['>=', 1000]}]

})

}

)Filter: Only orders $1000+ to this queue.

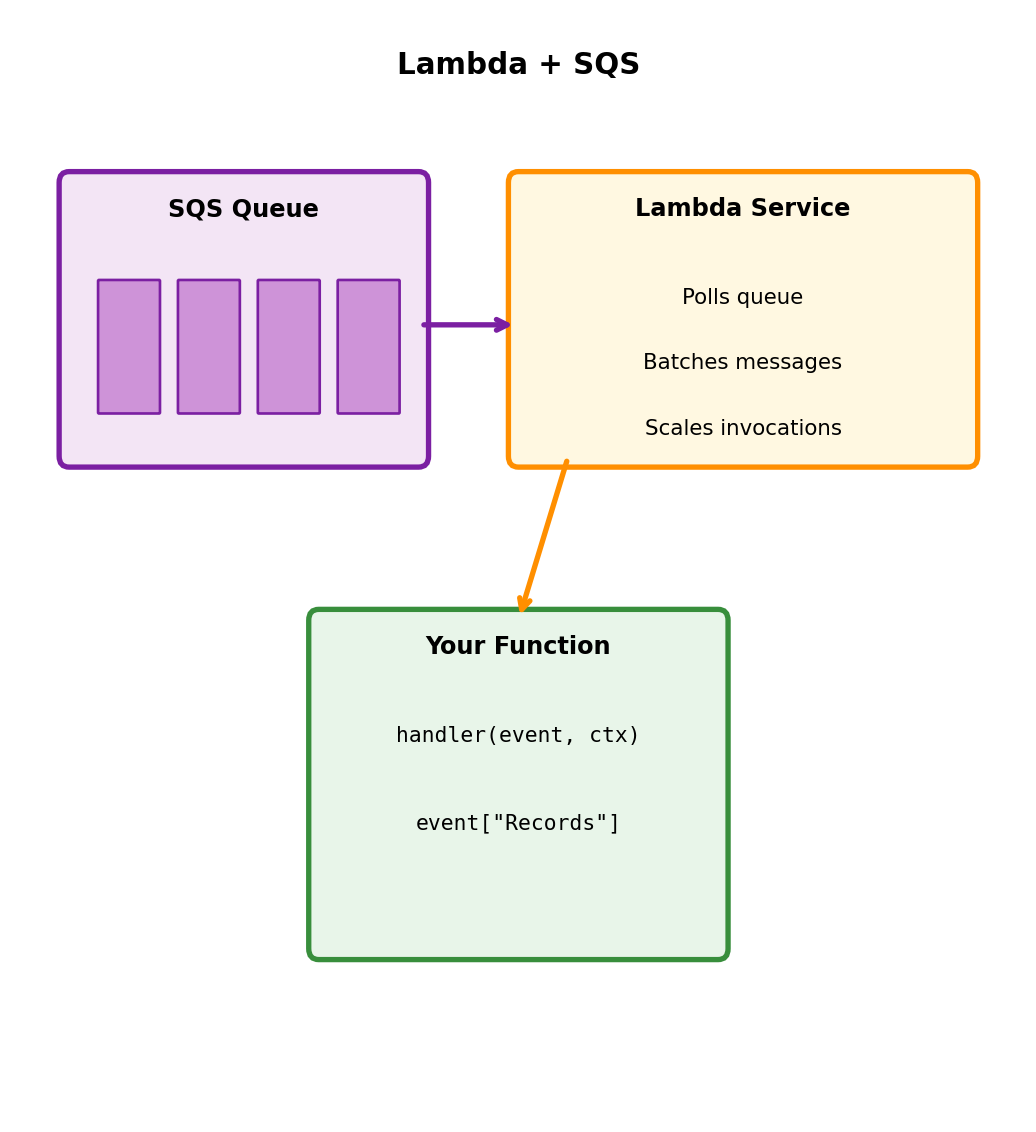

Lambda + SQS Integration

Lambda polls SQS automatically via event source mapping.

No polling code needed

def handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

body = json.loads(record['body'])

process_order(body)

# Success = messages deleted

# Exception = messages return to queueLambda service handles:

- Long polling

- Batching (1-10,000 messages)

- Scaling based on queue depth

- Visibility timeout

- Retry on failure

Batch size trade-off:

- Larger: Efficient (amortize cold start), harder failure handling

- Smaller: Simpler errors, more overhead

Partial Batch Failure Handling

Default: Exception fails entire batch. All messages retry, including already-processed ones.

Report which messages failed

def handler(event, context):

failed = []

for record in event['Records']:

try:

process(json.loads(record['body']))

except Exception as e:

failed.append(record['messageId'])

log.error(f"Failed {record['messageId']}: {e}")

return {

'batchItemFailures': [

{'itemIdentifier': mid}

for mid in failed

]

}Lambda deletes successful, returns failed to queue.

Requires: Enable ReportBatchItemFailures in event source mapping.

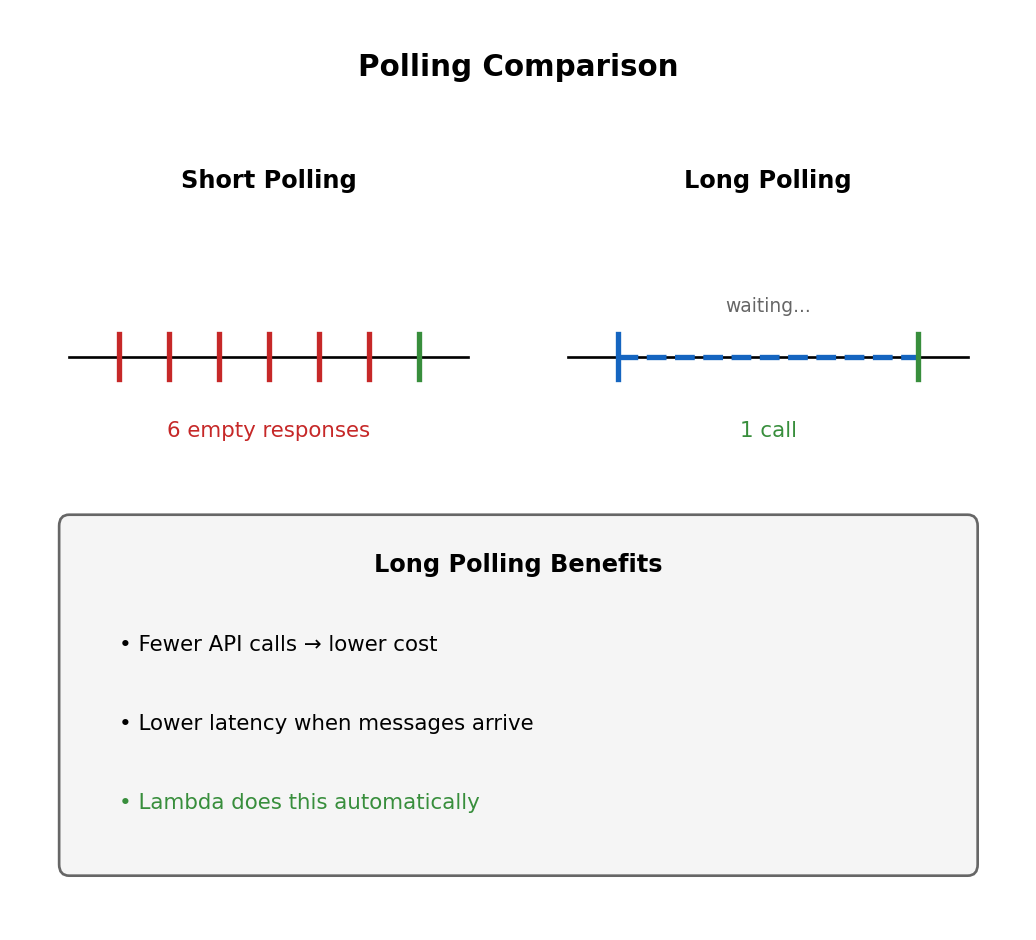

Long Polling

Short polling (default)

- Returns immediately, even if empty

- Many empty responses when queue idle

- Wasted API calls

Long polling

- Waits up to 20 seconds for messages

- Returns immediately when messages arrive

- Fewer calls, lower cost

# Short poll

response = sqs.receive_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MaxNumberOfMessages=10

)

# Long poll

response = sqs.receive_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MaxNumberOfMessages=10,

WaitTimeSeconds=20

)Lambda uses long polling automatically.

Message Delays

Delay processing for retry backoff, scheduled tasks, debouncing.

Queue-level delay

All messages delayed N seconds:

Per-message delay

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=json.dumps(data),

DelaySeconds=120 # This message only

)Max delay: 15 minutes

Longer delays: EventBridge Scheduler, database + polling, Step Functions.

Use cases

Retry backoff:

def requeue_with_backoff(msg, attempt):

delay = min(30 * (2 ** attempt), 900)

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=msg['Body'],

DelaySeconds=delay

)Debouncing:

# On file change, delay processing

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=json.dumps({'path': path}),

DelaySeconds=30 # Wait for more changes

)Scheduled task:

Batch Operations

SQS charges per API call, not per message.

Send batch (up to 10)

entries = [

{'Id': str(i), 'MessageBody': json.dumps(item)}

for i, item in enumerate(items[:10])

]

response = sqs.send_message_batch(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

Entries=entries

)

if response.get('Failed'):

for f in response['Failed']:

log.error(f"Failed: {f['Id']}")Delete batch (up to 10)

Cost impact

Throughput impact

- Individual: Limited by round-trip latency

- Batched: Amortize latency across 10 messages

Lambda batching

Lambda auto-batches receive/delete. Configure batch size 1-10,000.

Larger batches:

- More efficient

- Higher throughput

- Partial failure affects more

- Longer processing time

Large Messages: S3 Reference Pattern

SQS limit: 256 KB per message

Store in S3, send reference

def send_large_message(data, bucket):

payload = json.dumps(data)

if len(payload.encode()) > 200_000:

key = f"messages/{uuid.uuid4()}.json"

s3.put_object(Bucket=bucket, Key=key, Body=payload)

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=json.dumps({

'__s3_ref__': True,

'bucket': bucket,

'key': key

})

)

else:

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=QUEUE_URL,

MessageBody=payload

)Consumer retrieves from S3

def handler(event, context):

for record in event['Records']:

body = json.loads(record['body'])

if body.get('__s3_ref__'):

response = s3.get_object(

Bucket=body['bucket'],

Key=body['key']

)

payload = json.loads(response['Body'].read())

# Cleanup

s3.delete_object(

Bucket=body['bucket'],

Key=body['key']

)

else:

payload = body

process(payload)AWS Extended Client Library automates this.

Monitoring Queue Health

Key metrics

| Metric | Indicates |

|---|---|

ApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisible |

Backlog |

ApproximateNumberOfMessagesNotVisible |

In-flight |

ApproximateAgeOfOldestMessage |

How backed up |

NumberOfMessagesSent |

Producer throughput |

NumberOfMessagesDeleted |

Consumer throughput |

Healthy queue:

- Depth stable or near zero

- Age below threshold

- DLQ empty

Problems:

- Depth growing → consumers can’t keep up

- Age increasing → processing stalled

- DLQ filling → repeated failures

Alarms

# Queue depth

cloudwatch.put_metric_alarm(

AlarmName='high-queue-depth',

MetricName='ApproximateNumberOfMessagesVisible',

Namespace='AWS/SQS',

Dimensions=[{'Name': 'QueueName', 'Value': NAME}],

Threshold=10000,

ComparisonOperator='GreaterThanThreshold',

EvaluationPeriods=3,

Period=60

)

# Message age

cloudwatch.put_metric_alarm(

AlarmName='old-messages',

MetricName='ApproximateAgeOfOldestMessage',

Namespace='AWS/SQS',

Dimensions=[{'Name': 'QueueName', 'Value': NAME}],

Threshold=3600,

ComparisonOperator='GreaterThanThreshold',

EvaluationPeriods=2,

Period=60

)Decision Framework

Use synchronous

- User actively waiting

- Result needed to proceed

- Fast processing (sub-second)

- Simple request-response

Examples:

- Authentication

- Real-time queries

- Form validation

Characteristics:

- Tight coupling acceptable

- Failures visible to caller

- Scaling coupled

Use asynchronous

- User can continue without result

- Work can complete later

- Slow or variable processing

- Need failure isolation

- Need load buffering

- Different scaling needs

Examples:

- Order fulfillment

- Notifications

- Report generation

- Video transcoding

Characteristics:

- Decoupled in time

- Failures isolated

- Independent scaling

- Requires idempotency

Hybrid Pattern: Accept Sync, Process Async

@app.route('/orders', methods=['POST'])

def create_order():

# Sync: validate immediately

order = validate_order(request.json)

if not order.valid:

return {'error': order.errors}, 400

# Sync: save to database

order_id = save_order(order)

# Async: queue fulfillment

sqs.send_message(

QueueUrl=FULFILLMENT_QUEUE,

MessageBody=json.dumps({

'order_id': order_id,

'action': 'fulfill'

})

)

# Return immediately

return {'order_id': order_id, 'status': 'processing'}, 202User gets immediate confirmation. Fulfillment happens reliably in background.

Service Integration

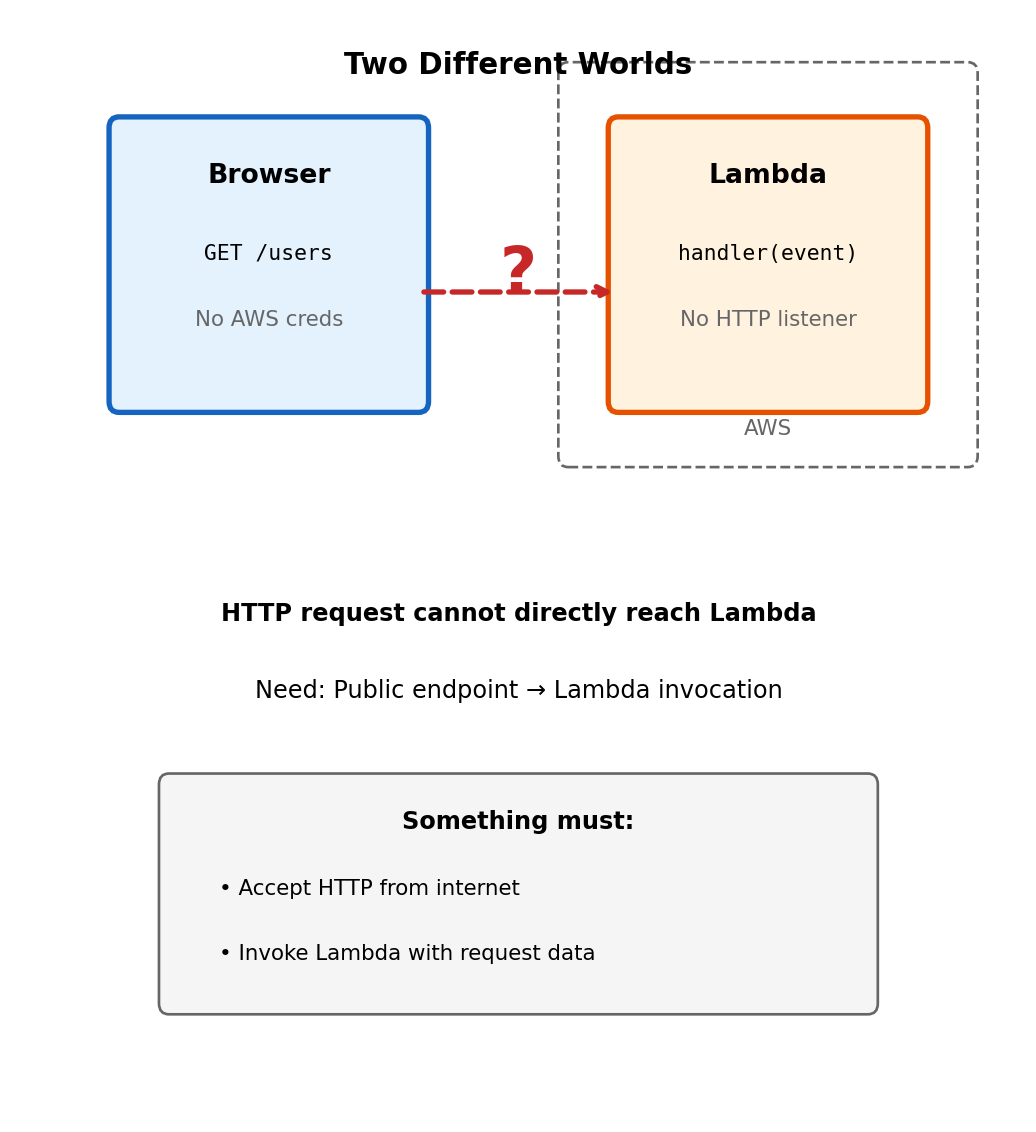

Lambda Runs Inside AWS, Not on the Internet

Lambda functions and HTTP requests live in different worlds

Lambda functions execute within AWS infrastructure. They can be invoked by AWS services (S3 events, SQS messages), but don’t listen on HTTP ports and don’t have public URLs.

How does a user’s HTTP request reach this function?

Direct Lambda invocation requires AWS credentials:

import boto3

lambda_client = boto3.client('lambda')

response = lambda_client.invoke(

FunctionName='my-function',

Payload=json.dumps({'name': 'test'})

)This works for service-to-service communication within AWS. But a browser making GET https://myapi.com/users cannot invoke Lambda directly - it doesn’t have AWS credentials, and Lambda isn’t listening on an HTTP port.

Connecting HTTP clients to Lambda requires something that accepts HTTP requests from the public internet and translates them into Lambda invocations.

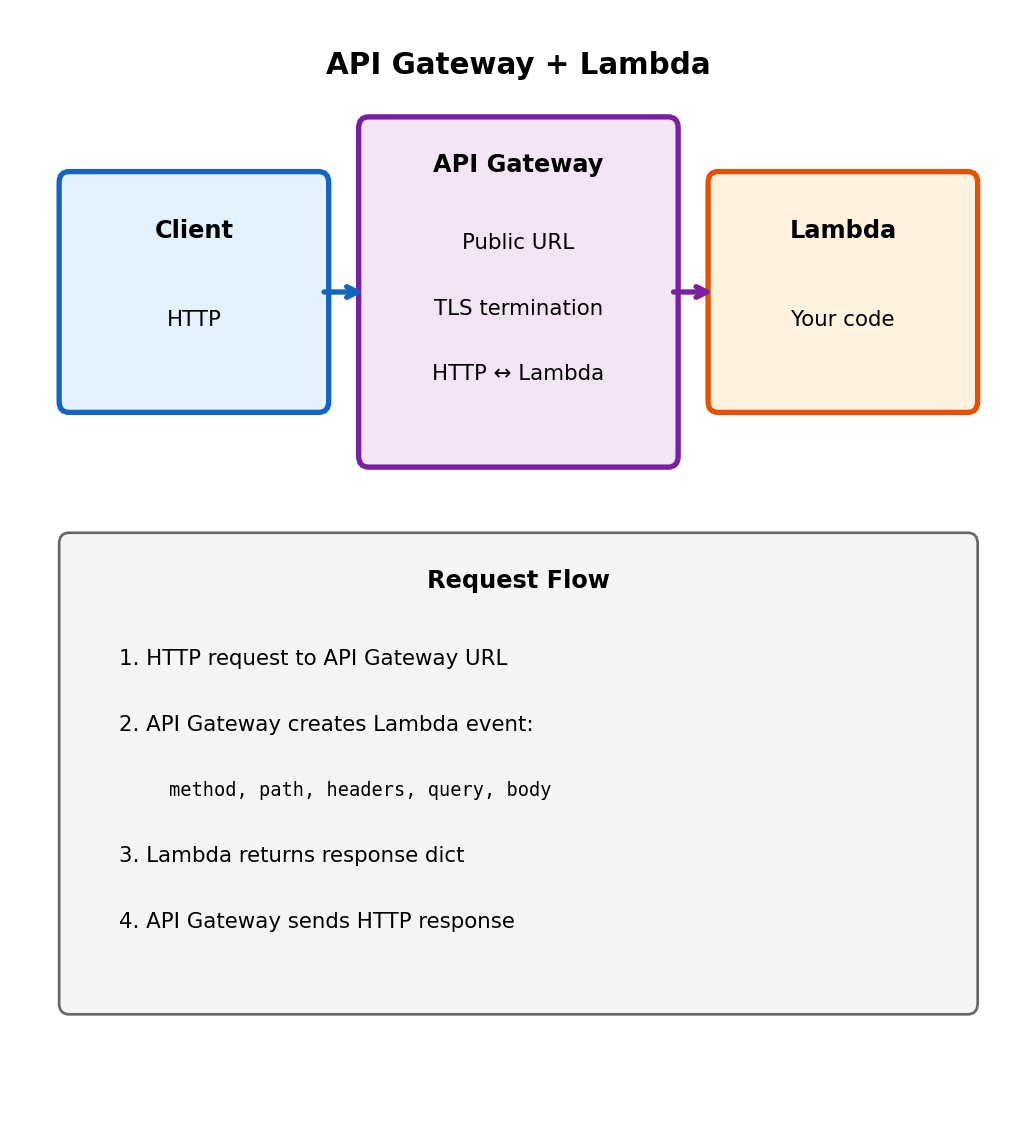

API Gateway Bridges HTTP and Lambda

API Gateway is a managed reverse proxy

It accepts HTTP requests at a public URL and routes them to backend services. For Lambda, it translates HTTP requests into Lambda invocations and Lambda responses back into HTTP responses.

https://abc123.execute-api.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/prod/users

└── API Gateway endpoint ──┘ └── path ──┘What happens on each request:

- Client sends HTTP request to API Gateway URL

- API Gateway validates request (optional)

- API Gateway invokes Lambda with event containing HTTP details

- Lambda executes, returns response object

- API Gateway translates response to HTTP

- Client receives HTTP response

The Lambda function never opens a port, never manages connections, never deals with TLS. API Gateway handles the HTTP protocol; Lambda handles the business logic.

You deploy the function, API Gateway provides the URL.

The Lambda Event From API Gateway

When API Gateway invokes your Lambda function, it passes the HTTP request as a structured event:

# Incoming HTTP request:

# POST /users?role=admin HTTP/1.1

# Host: abc123.execute-api...

# Content-Type: application/json

# Authorization: Bearer xxx

#

# {"name": "Alice"}API Gateway transforms this into:

Your handler processes and returns:

def handler(event, context):

method = event['httpMethod']

body = json.loads(event['body'] or '{}')

if method == 'POST':

user = create_user(body)

return {

'statusCode': 201,

'headers': {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

},

'body': json.dumps(user)

}

return {

'statusCode': 405,

'body': 'Method not allowed'

}API Gateway takes your return dict and constructs the HTTP response. Status code becomes HTTP status, headers become HTTP headers, body becomes response body.

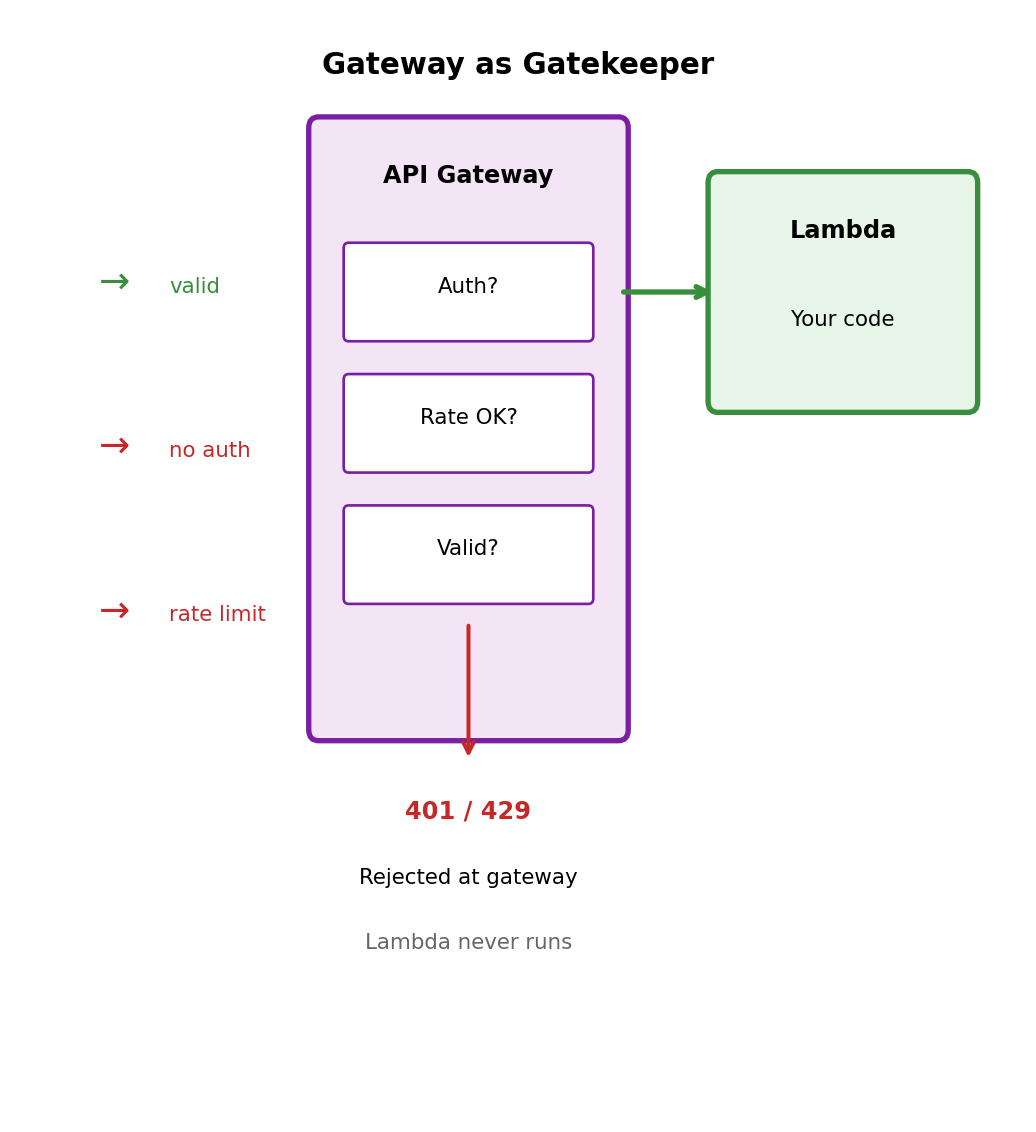

API Gateway Does More Than Route Requests

A reverse proxy handles cross-cutting concerns

Things every API needs, but you don’t want to implement in every function:

Authentication - Verify identity before code runs

- API keys (simple, but not secure alone)

- IAM authentication (for AWS-to-AWS)

- JWT tokens from Cognito or custom authorizer

- Request rejected at gateway if auth fails → Lambda never invoked

Rate limiting - Protect backend from overload

- Requests per second limits

- Burst allowances

- Per-client quotas via API keys

Request validation - Reject malformed requests early

- Required parameters

- Schema validation

- Fail at gateway, not in your function

Each of these protects your Lambda function. Invalid or excessive requests are rejected before they consume Lambda execution time (and cost).

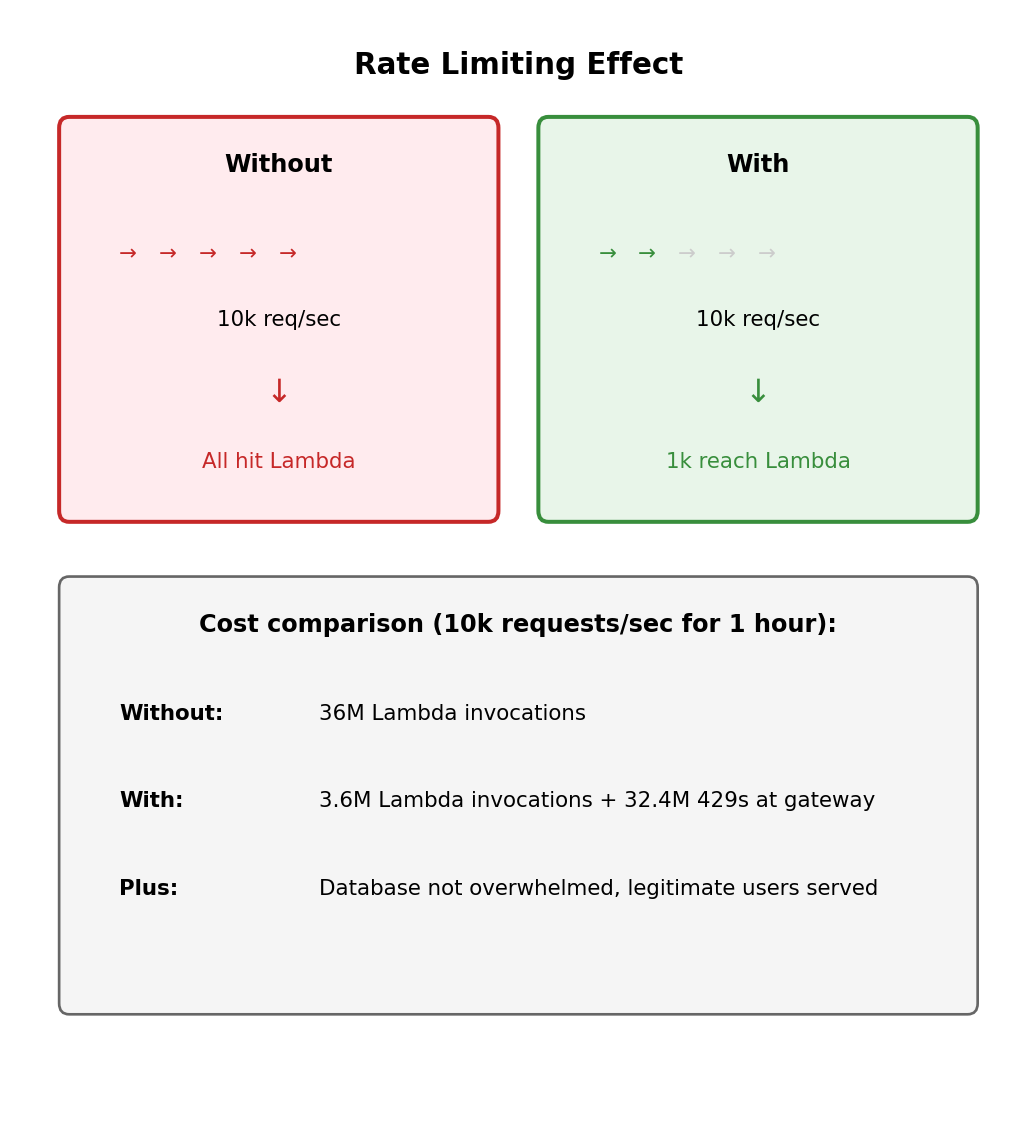

Rate Limiting Protects Your Backend

Without rate limiting

Your Lambda function is invoked for every request. Malicious or misconfigured client sends 10,000 requests/second:

- 10,000 Lambda invocations/second

- Each invocation costs money

- Downstream resources (database) overwhelmed

- Legitimate users affected

With rate limiting at the gateway

Excess requests receive HTTP 429 (Too Many Requests) immediately. They never reach Lambda, never hit your database, never cost you Lambda execution fees.

Client receives clear signal to back off. Gateway absorbed the attack; backend unaffected.

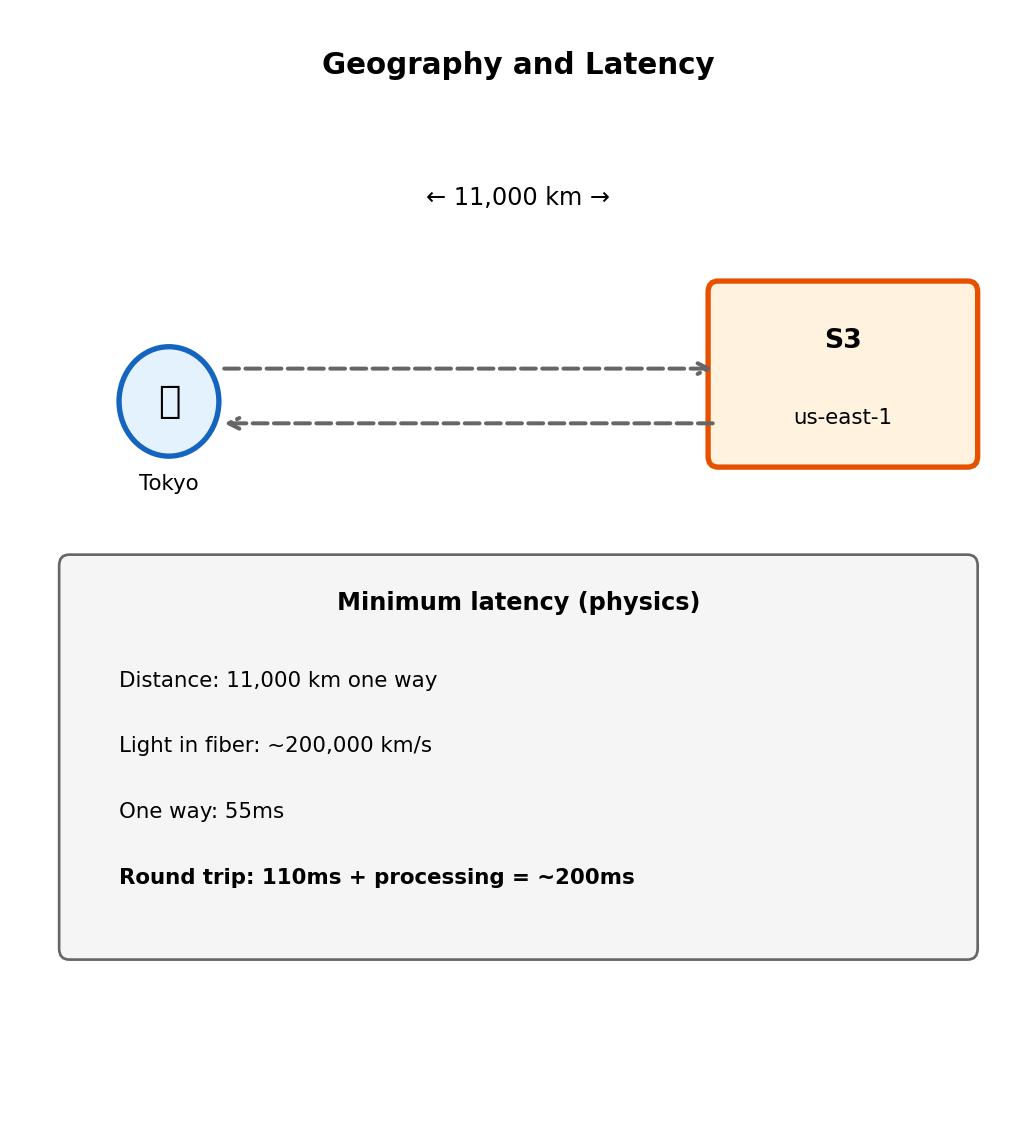

Static Content Latency: Geography Matters

S3 bucket location affects user experience

Images, CSS, JavaScript bundles, user-uploaded documents. S3 bucket is in us-east-1 (Virginia).

User in Tokyo requests an image:

- Request travels ~11,000 km to Virginia

- S3 retrieves object

- Response travels ~11,000 km back

- Round trip: 150-200ms minimum (speed of light)

For a web page loading 50 assets, that’s 50 × 200ms of latency-bound requests. Even with parallel loading, the page feels slow.

Latency here is physics, not performance.

Light travels at ~200,000 km/s through fiber. Tokyo to Virginia is 11,000 km. That’s 55ms one way, minimum. No optimization can beat the speed of light.

Reducing this latency requires putting content closer to users.

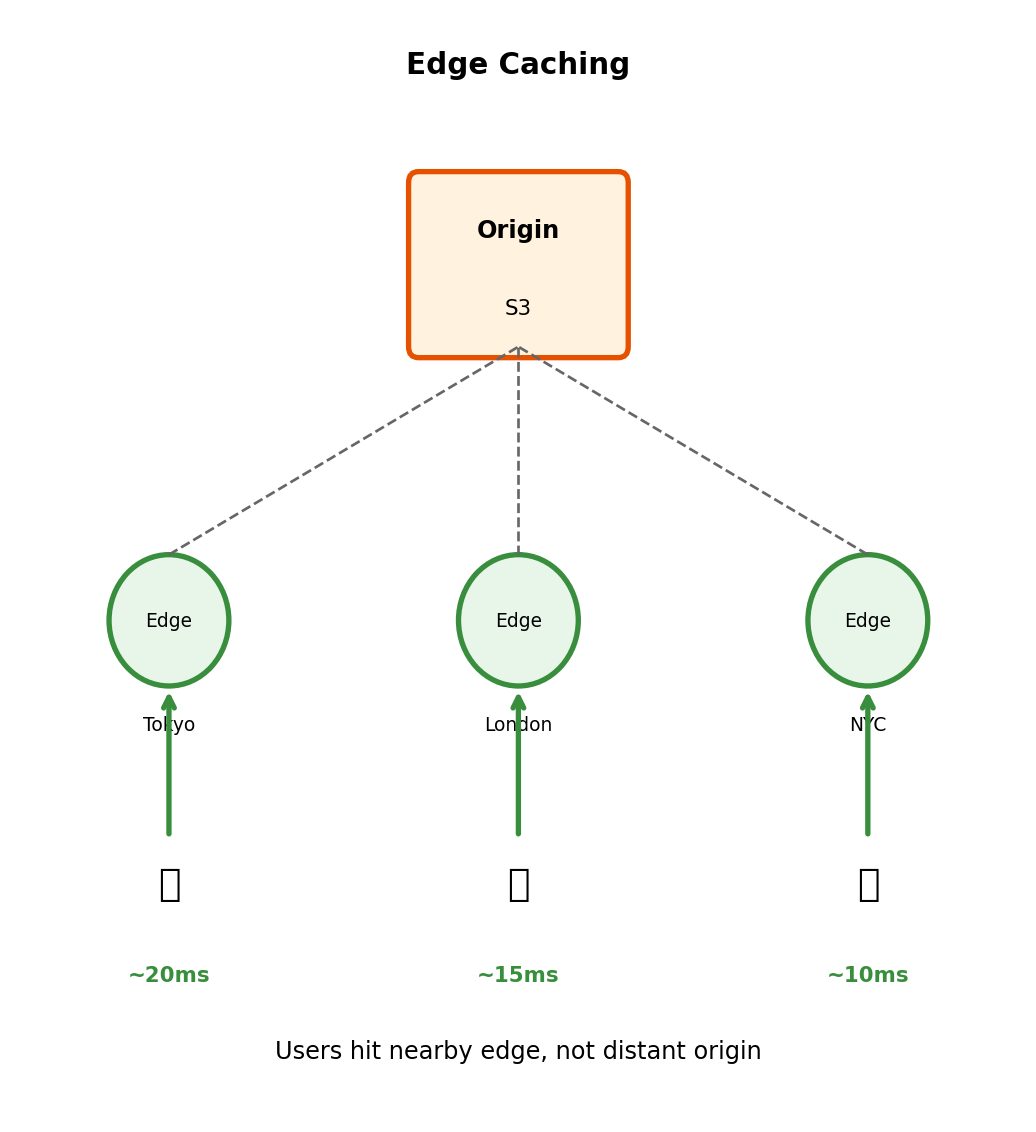

Edge Caching: Content Closer to Users

Content Delivery Network (CDN) concept

Instead of one origin in one region, cache copies at edge locations around the world. When a user requests content:

- Request goes to nearest edge location (low latency)

- If edge has cached copy → return immediately

- If not → fetch from origin, cache for next request

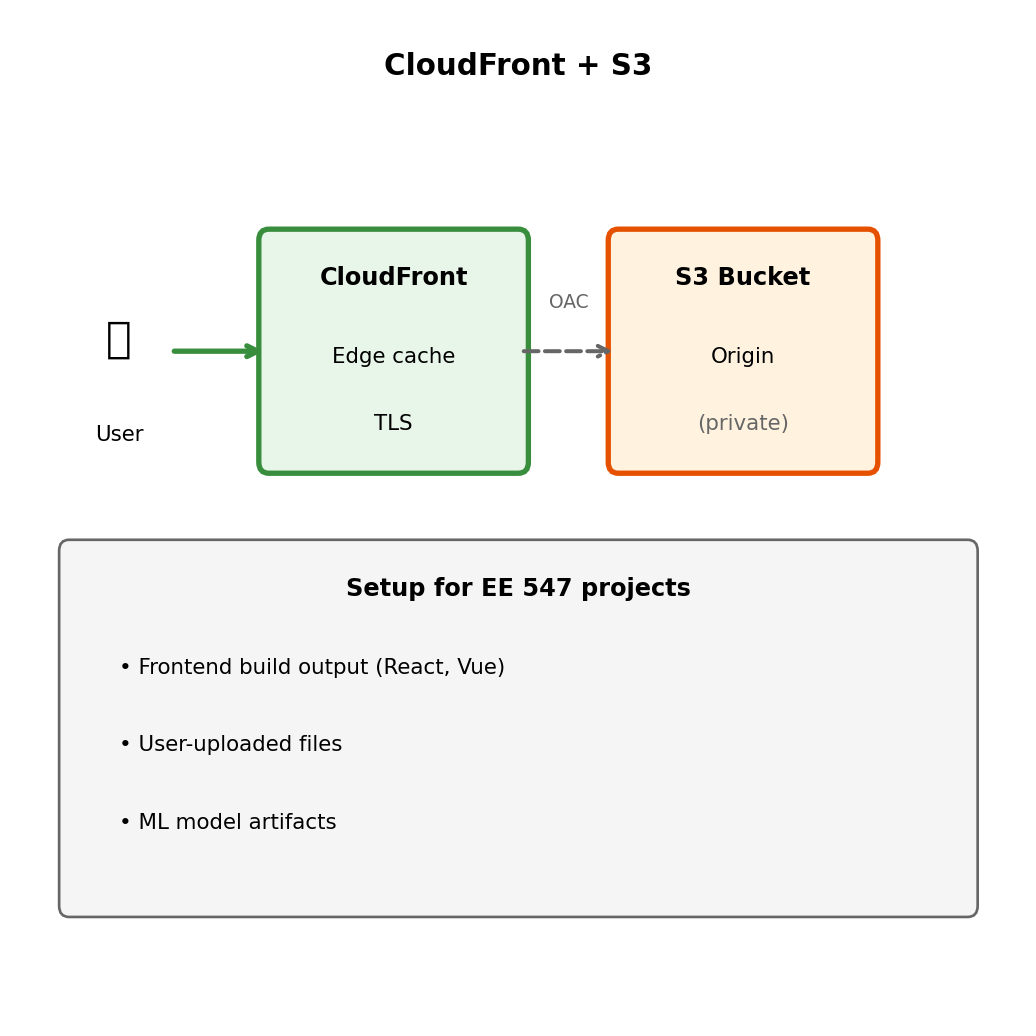

CloudFront: AWS’s CDN

- 400+ edge locations globally

- Integrates with S3, API Gateway, custom origins

- Provides custom domain + managed TLS certificate

First request (cache miss): User in Tokyo → Tokyo edge → S3 origin → Tokyo edge → User

Total: ~200ms (fetch from origin)

Subsequent requests (cache hit): User in Tokyo → Tokyo edge → User

Total: ~20ms (served from edge)

The edge location is physically close. Most requests hit cache. Latency drops dramatically.

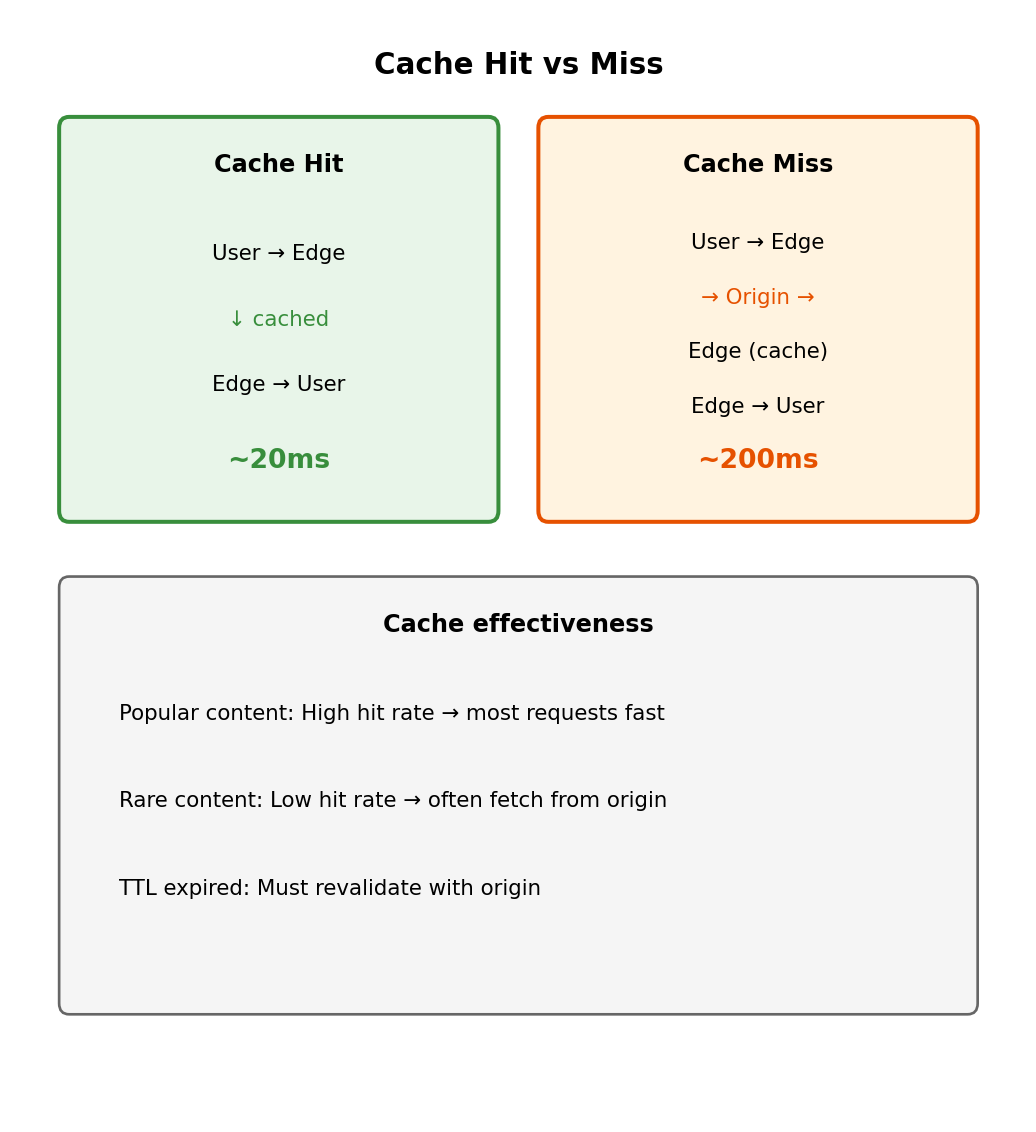

Cache Hit vs Cache Miss

Cache hit: Edge has the content

User → Edge: GET /images/logo.png

Edge: "I have this cached"

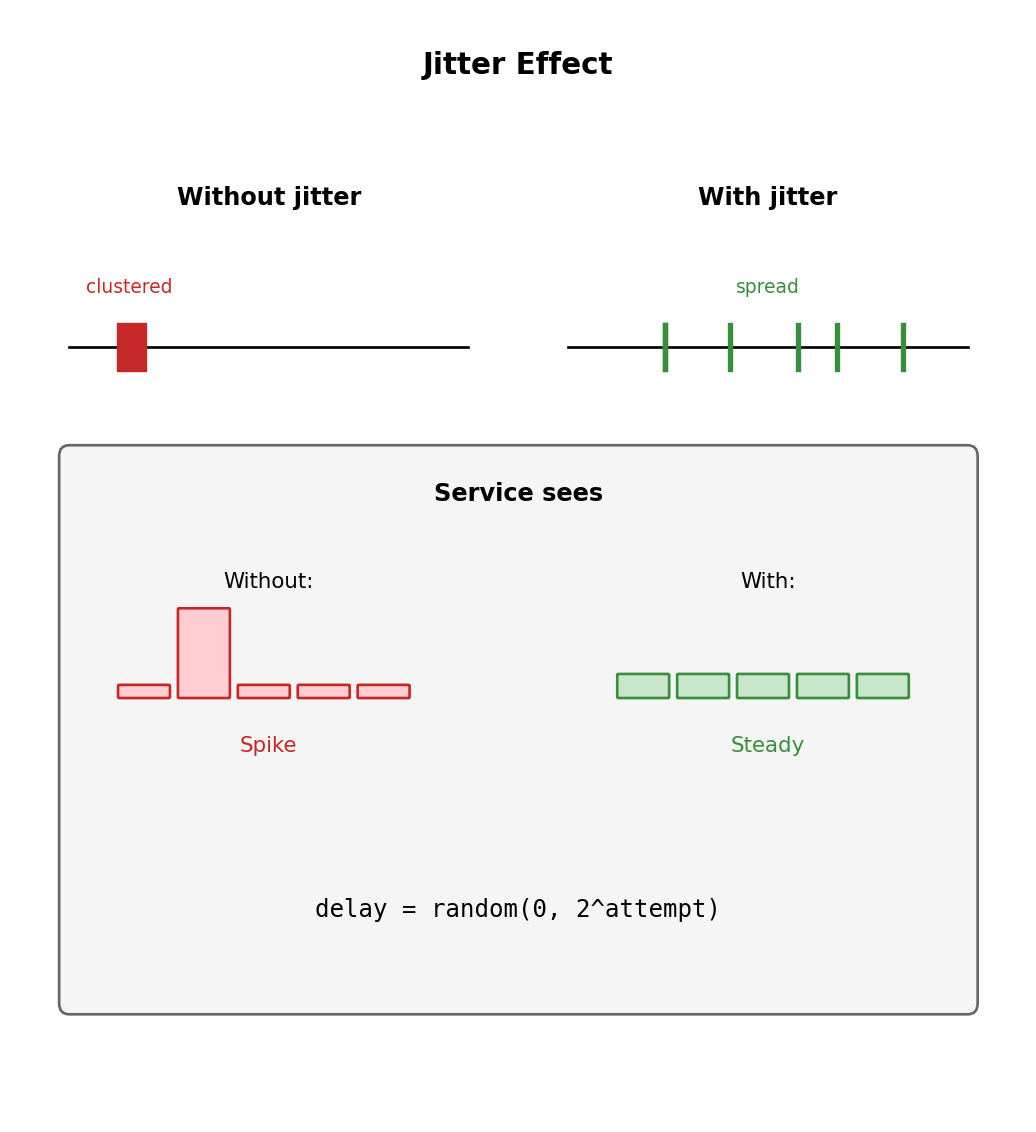

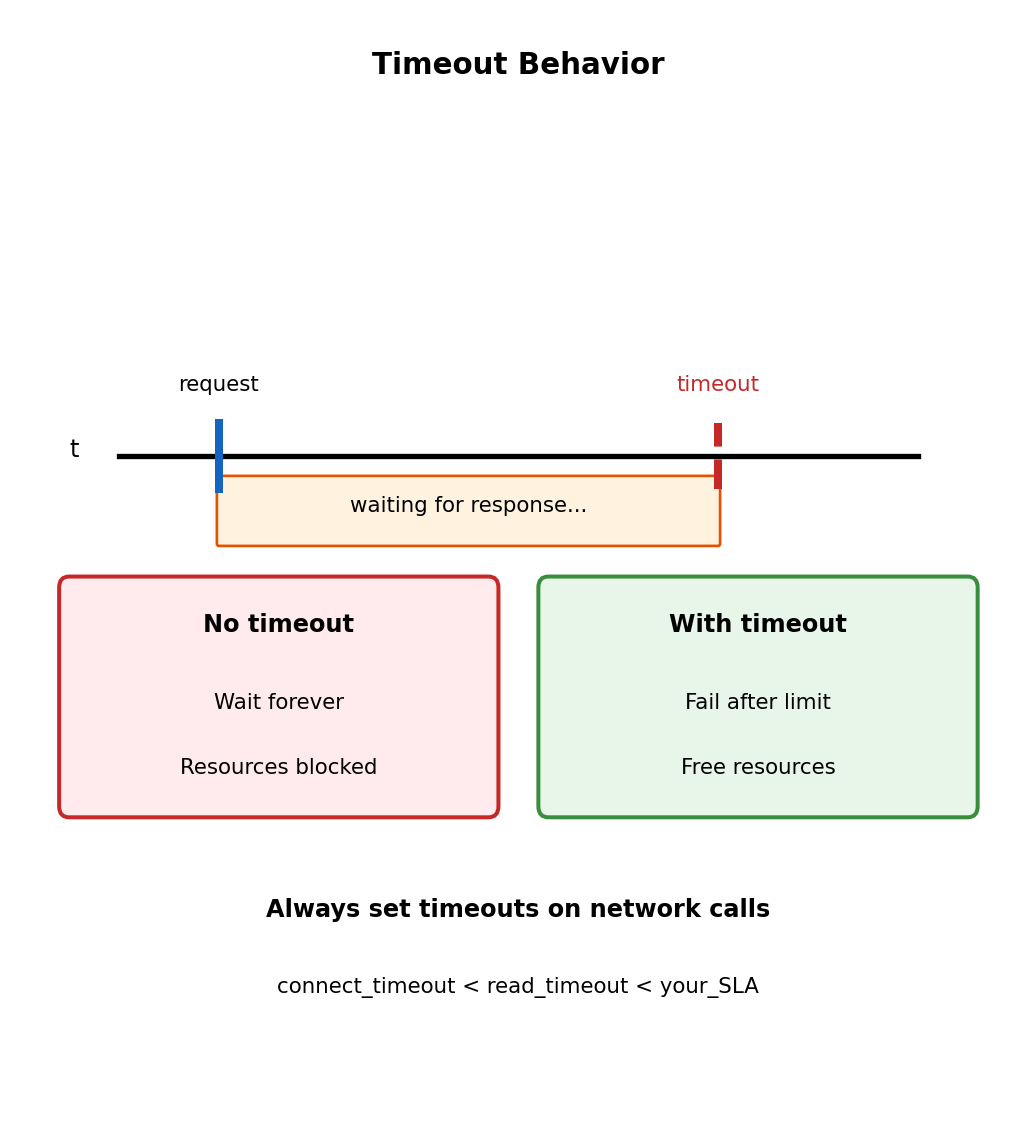

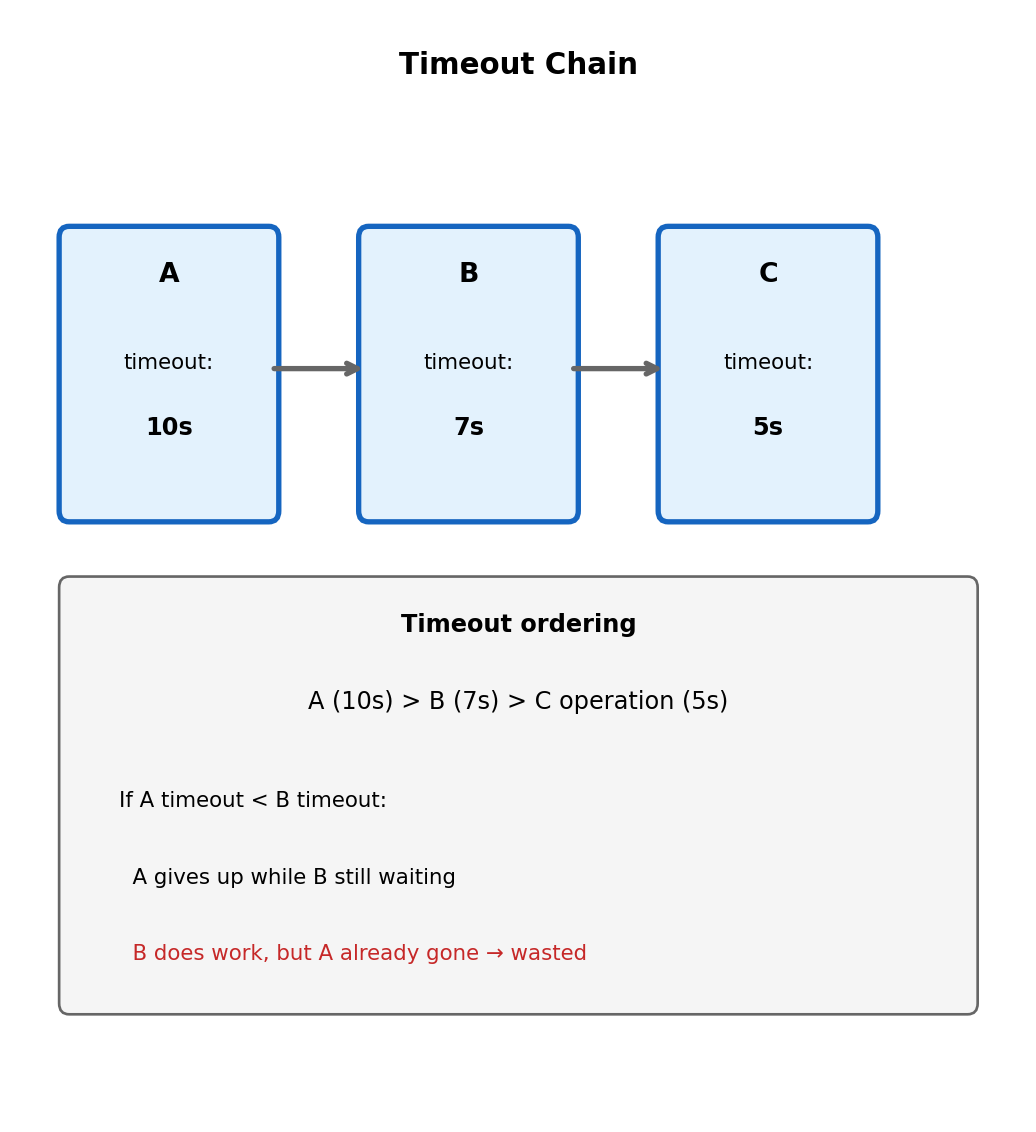

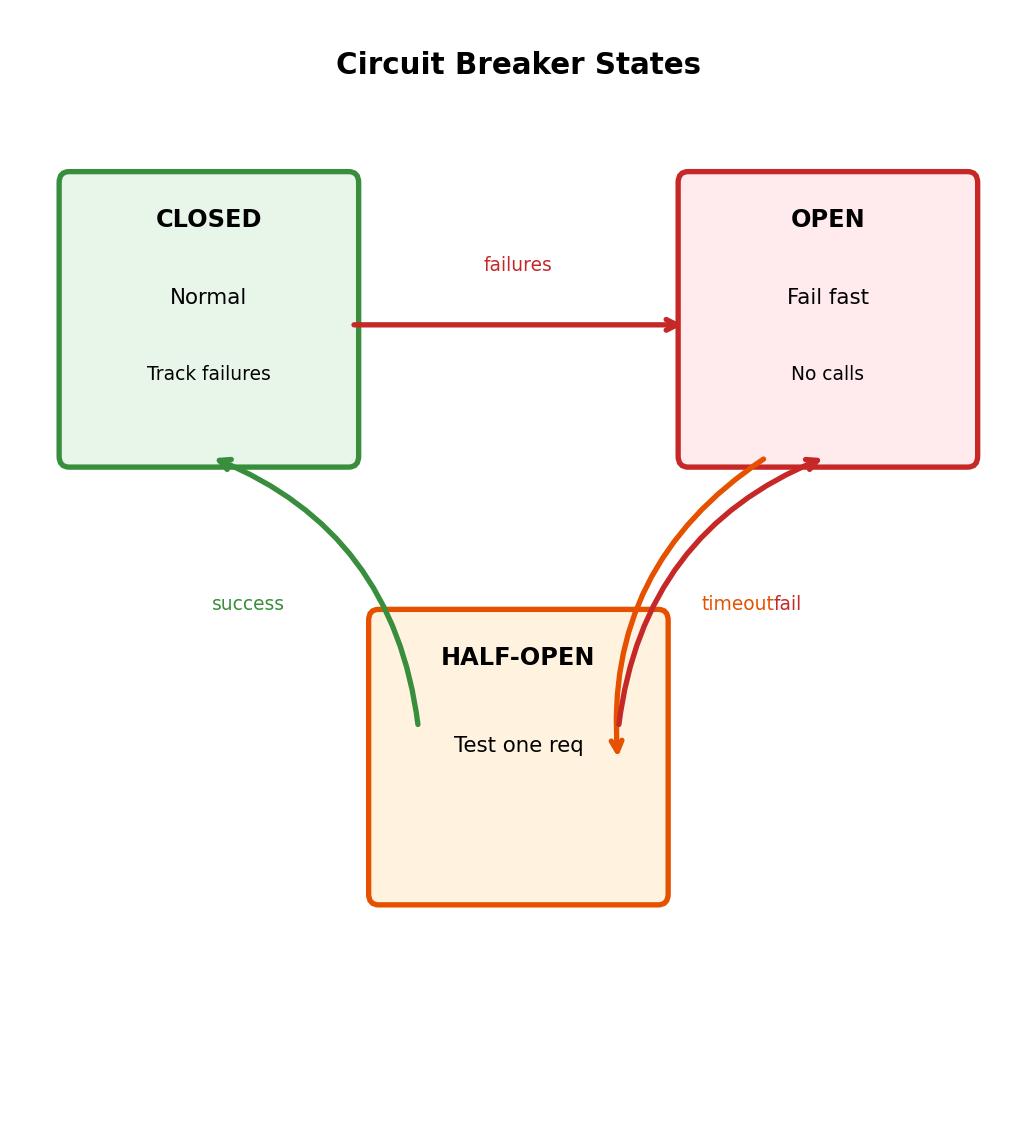

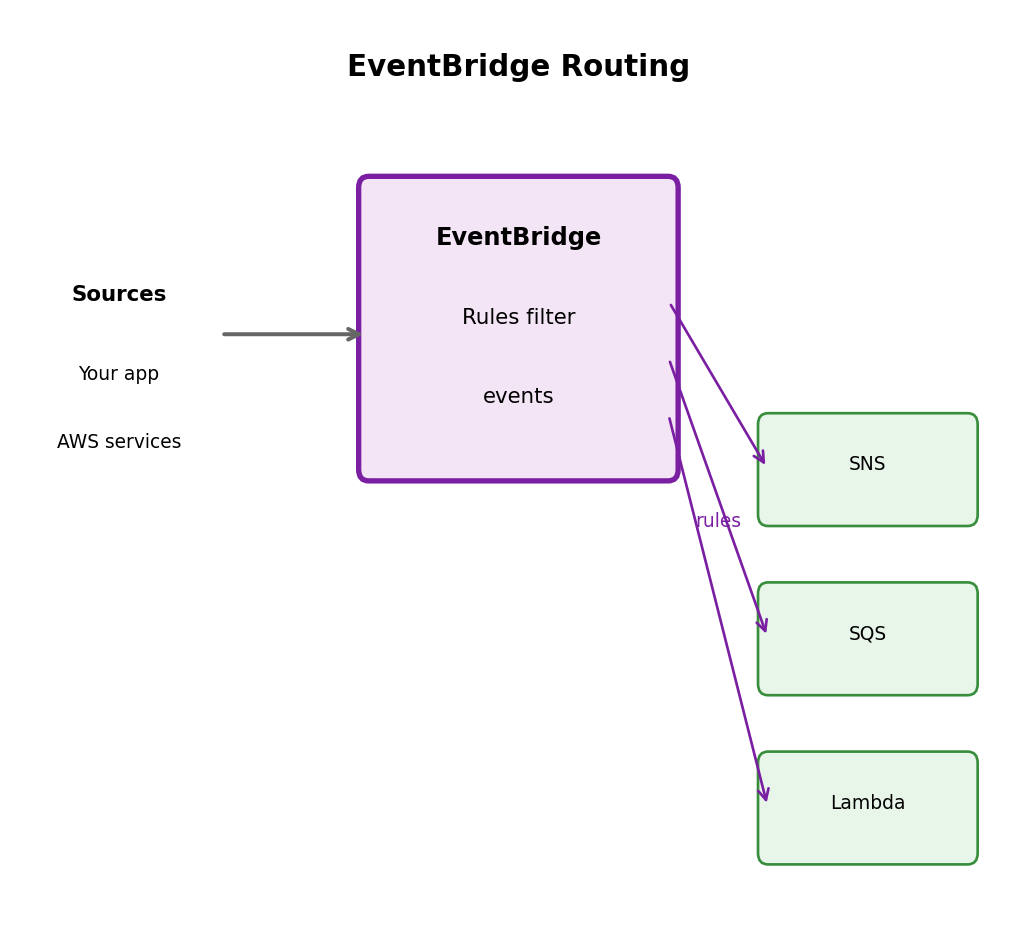

Edge → User: 200 OK (from cache)